the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Land subsidence dynamics and their interplay with spatial and temporal land-use transitions in the Douala coastland, Cameroon

Gergino Chounna Yemele

Philip S. J. Minderhoud

Leonard Osadebamwen Ohenhen

Katharina Seeger

Manoochehr Shirzaei

Pietro Teatini

The Douala coastland (DCL), situated within the Douala sedimentary basin along the Gulf of Guinea, is characterised by its low elevation and alluvial geology, making it particularly susceptible to coastal erosion, land subsidence, and relative sea-level rise. The DCL is home to numerous rapidly growing cities, such as Douala, Tiko, and Limbe, which are currently experiencing alarming rates of coastal erosion, frequent flooding, and significant loss of land. Regional and continental investigations have provided evidence of coastal subsidence in this region; however, knowledge of its drivers and impact on the DCL remains limited. To address this knowledge gap, interferometric synthetic aperture radar (InSAR) datasets from the Sentinel-1 C-band satellite were used to quantify vertical land motion (VLM) between 2018 and 2023 with respect to the IGS14 global reference frame and assumed to represents absolute VLM. Digital Elevation Model datasets were used to analyse the elevation of the study area. The results revealed that the rate of VLM ranges from −17.6 to 3.8 mm yr−1 (standard deviation of 0.2 mm yr−1), with a mean and median land subsidence rate of 2.7 and 2.5 mm yr−1. The analysis of land cover datasets from 1992 to 2022 suggests that urbanisation increased fivefold from 1992 to 2022 and that all contemporary urban areas experienced land subsidence, with the highest rates observed in non-residential zones with building heights ranging between 3 and 6 m. Subsidence rates of the DCL are inversely proportional to the time at which a particular land use and land cover (LULC) class changed into an urban area, highlighting the impact of the timing of LULC changes and urban expansion on present-day subsidence. The land subsidence rates decreased with an increase in building height, suggesting shallow land subsidence, where tall building usually with deep foundations are less prone to subsidence caused by groundwater extraction from the phreatic aquifer.

- Article

(13674 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(1769 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Land subsidence is a key environmental phenomenon that exacerbates coastal cities' vulnerability worldwide. Gambolati and Teatini (2021) described this geological phenomenon as a sudden or gradual settling of the land surface caused by changes in the stress regime of the subsurface structure driven by a combination of natural processes and human activities (Shirzaei et al., 2021; Candela and Koster, 2022). Recent research has revealed a global distribution of land subsidence processes (Herrera-Garcia et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2022; Davydzenka et al., 2024), ranging from arid to coastal zones, urbanised cities, and emerging cities. In urbanised coastal cities, land subsidence is often driven by a combination of natural processes and human activities, with a predominance of extensive groundwater extraction (Wu et al., 2022; Davydzenka et al., 2024; Huning et al., 2024). For instance, Tokyo, Japan (Cao et al., 2021), Beijing, China (Zhu et al., 2015; Zhou et al., 2019, 2020), California and New York, USA (Parsons et al., 2023; Ohenhen et al., 2024;), Rotterdam and Almere, Netherland (Koster et Al., 2018; Verberne et al., 2023; Maoret et al., 2024), Maceio, Brazil (Mantovani et al., 2024), and Venice, Italy (Teatini et al., 2005; Da Lio and Tosi, 2018), are prominent examples of cities experiencing significant land subsidence. In emerging countries, rapid urbanisation and inadequate infrastructure planning often exacerbate land subsidence, particularly in low-elevation coastal zones. Jakarta, Indonesia (Taftazani et al., 2022), the Mekong Delta, Vietnam (Minderhoud et al., 2017, 2018), and Lagos, Nigeria (Ohenhen and Shirzaei, 2022) are prime examples of such challenges.

From a global perspective, land subsidence can be seen as an environmental hazard that negatively impacts the lives of almost one-fifth of the global population (Herrera-Garcia et al., 2021; Minderhoud et al., 2024). Thus far, land subsidence remains underestimated despite the progressive increase in vulnerable populations and infrastructure, especially in rapidly growing cities (Minderhoud et al., 2024). In low-lying coastal areas, the combination of land subsidence and local sea-level rise often exacerbates coastal cities' exposure to inundation and flooding (Shirzaei et al., 2021). Apart from groundwater extraction, land-use changes and natural compaction of alluvial soils greatly influence the occurrence of land subsidence (Minderhoud et al., 2018; Zoccarato et al., 2018). Urbanisation, agricultural practices, and industrial activities are key factors in land-use change. The conversion of natural landscapes into urban areas typically involves the construction of heavy buildings and infrastructure that can compress underlying soils (De Wit et al., 2021; Parsons et al., 2023). Urbanisation often leads to increased groundwater extraction to meet the demands of a growing population, further contributing to land subsidence (Zhu et al., 2015). In many regions, intensive agriculture requires substantial water for irrigation, often sourced from groundwater (Tzampoglou et al., 2023). Industrial activities, particularly large-scale water use and hydrocarbon extraction, also contribute to the subsidence. For example, the Groningen gas field in the Netherlands has shown significant compaction and subsidence since early 1960, corresponding to the extraction period (Thienen-Visser and Fokker, 2017). Analogous to other deltaic regions globally, the Northern Adriatic has been characterised by land subsidence of both natural and, more recently, anthropogenic origin, with varying rates contingent upon geological events and human activities (Tosi et al., 2010).

Urbanised cities or urbanised coastal landscapes without major recent urbanisation dynamics such as Tokyo, Los Angeles, and Venice have implemented various measures to mitigate subsidence. In contrast, several emerging cities and landscapes that have urbanised recently, such as Douala and Lagos, are grappling with the rapidity of the urbanisation process and inadequate infrastructure. A lack of understanding of subsidence drivers poses additional challenges (Dinar et al., 2021). Coastal cities along the Gulf of Guinea in Africa fall within the second category and, therefore, there is a need for detailed scientific investigations to understand the geomorphological mechanisms going on this zone. The Gulf of Guinea is known to be lowly elevated above sea level (Hauser et al., 2023) and bears major rapidly growing cities such as Douala, Lagos, Cotonou, Accra, Abidjan, and Saint-Louis. Tens of millions of inhabitants live there, and the coastlands bear the countries' respective critical infrastructure (Cian et al., 2019; Dada et al., 2023). The coastline is particularly exposed to erosion and sea-level rise (Ideki and Peace, 2024; Dada et al., 2024), and land subsidence exacerbates these processes, as evidenced by preliminary land subsidence investigations in Nigeria (Ohenhen and Shirzaei, 2022; Ikuemonisan et al., 2023), Ghana (Avornyo et al., 2023; Brempong et al., 2023), and Senegal (Cisse et al., 2024). In contrast, there have been no specific studies on land subsidence mechanisms for the coast of Cameroon, leaving it uncharted.

This study aims to fill the knowledge gaps regarding the land subsidence mechanism in the DCL. It is motivated by the necessity of quantifying land subsidence in the DCL, and understanding the driving mechanisms. Investigating the relations between land subsidence and land-use land cover changes in the DCLtherefore constitutes the first step to unravel the interlinkages between vertical land motion, physical setting and human activities along the coast of Cameroon.

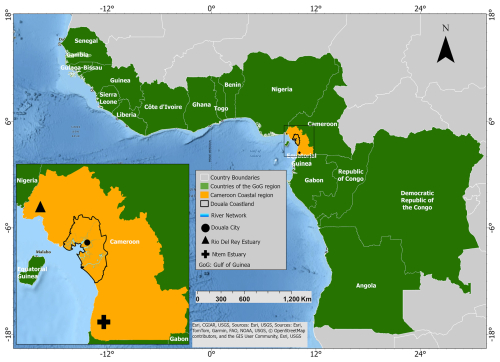

The coastline of Cameroon, located in the eastern part of the Gulf of Guinea (Fig. 1), covers over 400 km from the border with Equatorial Guinea in the southeast to the border with Nigeria in the northwest (Ondoa et al., 2018). The coast bears several river outlets, including the Sanaga River, Nyong River, Lobe, and Ntem rivers, as well as very important estuaries such as the Ntem estuary (from 3°34′ N, 9°38′ E to 2°20′ N, 9°48′ E), Cameroon estuary (3°58 N, 9°17′ E to 3°34′ N, 9°38′ E), and Rio Del Rey estuary (from 4°30′ N, 8°30′ E to 4°14′ N, 8°56′ E) (Ondoa et al., 2018). The Cameroon Estuary, also known as the Wouri Delta, is located at the heart of the Douala sedimentary basin (19 000 km2), and hosts the city of Douala, which is one of the most important cities of Cameroon (Fossi et al., 2023). From a hydrological perspective, the Wouri estuary is drained by three coastal rivers, Mungo, Wouri, and Dibamba, with average annual flows of 8109, 16 109, and 4109 m3 s−1, respectively (Fossi et al., 2023). The Wouri Delta is a critical region in Cameroon because of its rich biodiversity, economic significance, social and cultural value for local communities (Ondoa et al., 2018).

Figure 1Countries of the Gulf of Guinea region bordering the Atlantic Ocean. The coastline of Cameroon is bounded by the Ntem estuary in the southeast and the Rio Del Rey estuary in the northwest. The inset shows the study area (Douala Coastland), Douala City, and Rio Del Rey. Basemap source: Esri.

The coastland of Cameroon is characterised by low-lying topography and wetlands dominated by mangroves, which are exposed to the constant threat of flooding (Kenneth, 2009; Ellison and Zouh, 2012). The wetlands are geomorphologically fragile zones prone to compaction, and human activities have intensified the alteration of the hydrogeomorphic characteristics of the area over time. In an area where the abundance of surface water in wetlands coexists with a scarcity of land, the challenge of exposure is further exacerbated by increasing population and anthropogenic activities. These changes include the conversion of wetlands for housing, industrial development, and the expansion of highways, whereas natural changes are caused by saltwater intrusion and land subsidence (Kenneth, 2009). In addition, Douala is the largest city and economic capital of Cameroon and bears the most important infrastructure, with a population of approximately 4 million inhabitants in 2022. The city shows a similar geomorphological and urban setting as other African (mega)cities affected by land subsidence; however local evidence of land subsidence does not exist for Douala so far but has only been indicated by studies on global and continental scale (see Cian et al., 2019; Davydzenka et al., 2024).

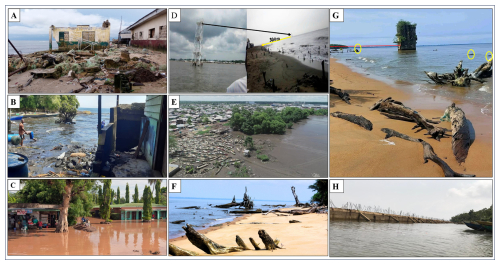

The low-lying coastal areas of Cameroon, particularly in regions such as the Douala coastal lowland and Rio Del Rey Estuary, are increasingly susceptible to a combination of sea-level rise, coastal erosion, flooding, and land subsidence (Fossi et al., 2019). Relative sea-level rise attributed to climate change and land subsidence exacerbates the impact of coastal flooding, rendering previously infrequent flood events more common and severe (Fossi et al., 2019). This elevated water level contributes to increasing erosion of the coastline, progressively diminishing land and exposing local inhabitants, infrastructure, livelihoods, and ecosystems (Fig. 2). Coastal erosion, intensified by frequent storms, induces shoreline retreat and destabilises coastal communities (Fossi et al., 2019). Traces of the impacts of these hazards along the low-lying coast of Cameroon are shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2Environmental hazards along the low-lying coast of Cameroon. (A) Destruction of school infrastructure due to intensified coastal erosion as a result of sea-level rise in Bakassi, Rio Del Rey Estuary (Wantim and Ngeh Ngeh, 2025). (B) Destruction of houses by sea-level rise and coastal erosion in Desbundscha (Wantim et al., 2021). (C) Flooding in coastal city along the Gulf of Guinea (Editor, 2024). (D) Shift of the coastline by 300 m over 30 years on Cap Cameroon Island (Fossi et al., 2019). (E) Shoreline retreat in Douala as a result of relative sea-level rise (Sikem, 2021). Panels (F)–(H) highlight the exposure of Manoka Island to sea-level rise, coastal erosion, and potential land subsidence. For (G), the yellow circle highlights a remaining tree trunk submerged in the waterbody, indicating that this area was previously emerged land. The red line indicates the distance between the current shoreline and the submerged building. (F–H) Photos taken in 2023 by author.

Pluvial flooding, which is a significant concern due to heavy rainfall, can be further aggravated by elevation lowering in areas affected by land subsidence (Miller and Shirzaei, 2019; Huning et al., 2024).

3.1 Delineation of the Douala Coastland

Elevation was used to delineate the study area from the entire littoral region. Applying an elevation threshold allows to focus on the lowly elevated coastal areas which are particularly exposed to relative sea-level rise and related coastal hazards in the context of climate change. We used the digital elevation model (DEM) NASADEM Merged DEM Global 1 arcsec V001 and considered areas of the states bordering the Gulf of Guinea with elevations below 100 m (WGS84/EGM96 datum) as the area of interest (NASA, 2021).

3.2 SAR Data and Interferometric Analysis

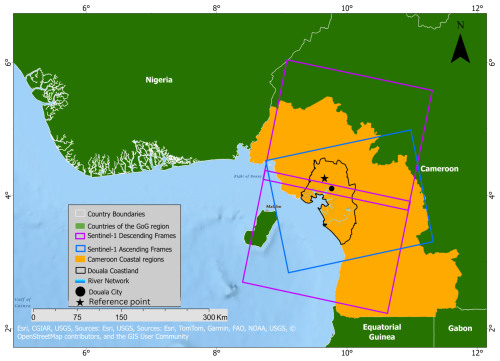

We used synthetic aperture radar (SAR) data acquired from the Sentinel-1 C-band satellite to generate a land displacement map for DCL. The analysis processed 313 SAR images acquired with the Interferometric Wide (IW) swath mode in ascending (frame 132, path 1192) and descending (frame 51, paths 575, and 580) orbit geometries between 10 March 2018, and 17 June 2023. Figure 3 and Table S1 in the Supplement show the footprints of the SAR frames and inventory of images, respectively. We utilised GAMMA software (Werner et al., 2000) to generate a set of 1197 interferograms, employing a SBAS-type algorithm with a pair selection strategy optimized through dyadic temporal downsampling and Delaunay triangulation to minimize phase closure errors and temporal decorrelation (Lee and Shirzaei, 2023). The interferometric pairs were constrained to a maximum temporal and perpendicular baselines of 300 d and 80 m, respectively. To improve the signal-to-noise ratio of the interferometric phase, a multi-looking factor of 32 (range) by 6 (azimuth) was used to create a pixel dimension of ∼ 75 m, representing a trade-off between noise suppression over natural terrain and the preservation of spatial detail in urban environments. To generate high-spatial-resolution maps of land displacement over the study area, advanced multi-temporal wavelet-based interferometric synthetic aperture radar (InSAR) analysis was applied to the interferograms (Shirzaei and Bürgmann, 2012; Shirzaei, 2013; Lee and Shirzaei, 2023). The wavelet-based analysis involves identifying and removing noisy pixels, reducing the effects of topographically correlated atmospheric phase delay and spatially uncorrelated DEM error. To this end, we identified and removed noisy pixels following Lee and Shirzaei (2023), by applying a statistical framework that selects elite pixels accounting for distributed and permanent scatterers. Permanent scatterers (PS) were identified using an amplitude dispersion index < 0.3 (Ferretti et al., 2001), while distributed scatterers (DS) were assessed using the mean and variance of coherence values across the interferogram stack. DS pixels with an average coherence > 0.65 and low coherence dispersion (Fig. S4) were retained and assigned to Voronoi cells constructed around adjacent PS. Within each Voronoi cell, a Fisher's F-test was used to evaluate variance homogeneity between DS and PS amplitude histories. DS pixels passing this test were reclassified as permanent-distributed scatterers (DSp). The final set of elite pixels therefore comprised PS and DSp (see Lee and Shirzaei, 2023 for further details). Next, the 1 arcsec (∼ 30 m) Shuttle Radar Topography Mission digital elevation model (Farr et al., 2007) was used to calculate and remove the effects of the topographic phase and flat Earth (Franceschetti and Lanari, 1999). A 2D minimum cost flow phase unwrapping algorithm modified to be applied to a sparse set of elite pixels was to estimate absolute phase changes in each interferogram (Costantini, 1998; Costantini and Rosen, 1999). We corrected for the effects of orbital error (Shirzaei and Walter, 2011), spatially uncorrelated topography error, and the topography-correlated component of atmospheric delay by applying a suite of wavelet-based filters (Shirzaei and Bürgmann, 2012). Finally, the line-of-sight (LOS) time series and velocities for each elite pixel were computed using a local reference point (longitude: 9.61, latitude: 4.22) located in a stable area within the broader Douala coastland region but outside the urban center. The LOS displacement velocity was estimated using the reweighted least-squares method as the slope of the best-fitting line to the associated time series, while the standard deviation of the LOS velocity corresponds the uncertainty of the regression slope. The LOS displacement velocities and associated standard deviation values for the ascending and descending orbit geometries are presented in Figs. S1 and S2, respectively.

Figure 3Footprint of InSAR images (ascending and descending Sentinel-1A/B) in the Douala coastland, including the position of the local reference point. Basemap source: Esri.

In areas with overlapping spatiotemporal SAR satellite coverage and different viewing geometries (i.e., ascending and descending), surface deformation can be resolved. However, because of the near-polar orbits of the Sentinel-1 satellites, which may cause low sensitivity in the north-south component, only the east-west and vertical components can be reliably retrieved (Wright et al., 2004). Assuming that the deformation in the north-south direction is negligible, we estimate the horizontal (east-west) and vertical components of deformation by jointly inverting the LOS time series of the ascending and descending tracks (Miller and Shirzaei, 2015; Ohenhen and Shirzaei, 2022). Thus, we first identified the co-located pixels of the LOS time series by resampling the pixels from the descending track onto the ascending track to obtain two co-located LOS displacement velocities. Given {LOSA,LOSD} and are the LOS displacement and variances for a given pixel, where the subscripts A and D indicate the ascending and descending tracks, respectively. The model computed the horizontal (dx) and vertical (dz) components from the LOS displacement as shown in Eq. (1):

where Cx and Cz are the unit vectors projecting the 2D displacement (horizontal and vertical) field onto the LOS direction, which are a function of the heading and incidence angles for each pixel (Hanssen, 2001). The solution to Eq. (1) is given by Eq. (2):

where X represents the unknowns (dx and dz), G is the Green's function given by the unit vectors (Cx and Cz), P is the weight matrix, which is inversely proportional to the variances of the observations ( and ), and L is the observation (LOSA and LOSD). Next, we employ the concept of error propagation (Mikhail and Ackermann, 1982) to obtain the associated parameter uncertainties given the observation errors. Thus, the variance-covariance matrix of the horizontal and vertical components was calculated using Eq. (3):

The horizontal velocity, VLM rate, and standard deviation are shown in Fig. S3A and B, respectively (see the Supplement). To transform the VLM from a local frame to a global reference frame, we employed the global VLM model by Hammond et al. (2021), which mostly contains long-wavelength deformation signals (i.e., glacial isostatic adjustment (GIA), hydrological loading, and tectonics), and applied an affine transformation following Blackwell et al. (2020) and Ohenhen et al. (2023) to align the VLM rates with the IGS14 global reference frame. The IGS14 global reference frame was used because the study area has no GNSS station to serve as a local reference point and helps to improve the accuracy, calibration, and interpretation of the InSAR measurements.

3.3 Land use, land cover (LULC) and human settlement data analysis

We investigate trends in and spatiotemporal correlations between land subsidence and past land-use changes, following an approach similar to that of Minderhoud et al. (2018). The analysis included the InSAR data described in the previous section and a collection of Land-Use Land Cover (LULC) data that was prepared (reclassified) for spatial and temporal analysis. To further investigate the relations between land subsidence and urban built-up areas, we integrated additional information characterising built-up settlements.

Information on LULC was obtained from the European Space Agency (ESA) global land cover data for the period of 1992 to 2015 with a resolution of 300 m (ESA Land Cover CCI project team and Defourny, 2019), and Esri Land Cover products for the period of 2017 to 2022 with a resolution of 10 m. We use the Esri's Land Cover (Esri) products for the most recent years as it shows a high accuracy than the ESA land cover dataset (Venter et al., 2022).

Information about the setting of built-up areas was obtained by using the urban built-up surface data (GHS-BUILT-S; Pesaresi and Politis, 2023c), built-up volume data (GHS-BUILT-V; Pesaresi and Politis, 2023d), spatial built-up height data (GHS-BUILT-H; Pesaresi and Politis, 2023b), spatial population raster density (GHS-POP; Schiavina et al., 2023), and morphological settlement zone characteristics (GHS-BUILT-C; Pesaresi and Panagiotis, 2023a). All these datasets were acquired from the Global Human Settlement Layer (GHSL) website. The concept and methodology used to obtain GHSL data were described in European Commission (EC) (2023) for GHS-BUILT-S, GHS-BUILT-C, and GHS-BUILT-V data; Pesaresi and Politis (2023b) for GHS-BUILT-H data; and Freire et al. (2016) for GHS-POP. Recent similar applications of GHSL datasets for land subsidence studies are illustrated by the work of Verberne et al. (2025) and Cigna et al. (2025).

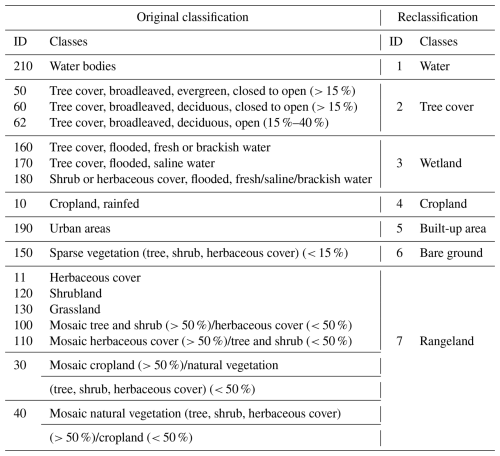

The data were pre-processed to ensure quality and consistency between the LULC classes of different years. This involves aligning spatial data layers to a common coordinate system and resolution, extracting data for the study area, and reclassifying the LULC data to classes appropriate for the goal of this study. The reclassification of land cover data was performed only for the ESA global land cover data from 1992 to 2015 to reduce the number of classes by unifying them and making them similar to Esri's land cover classes. This was performed using ArcGIS Pro 3.2 Spatial Analyst tools. The original 17 land cover classes were reclassified into 7 new classes as shown in Table 1. The LULC classes from 2017 to 2022 were not reclassified as they already met the scope of our analysis.

Table 1Land-use and land-cover reclassification table for the European Space Agency (ESA) dataset (land-cover data 1992–2015).

We produced LULC maps of the DCL for the year 1992, 2007, 2015, 2017, and 2022 using ArcGIS Pro 3.2. The statistics for each land cover class in each year were retrieved using Excel and Power BI software.

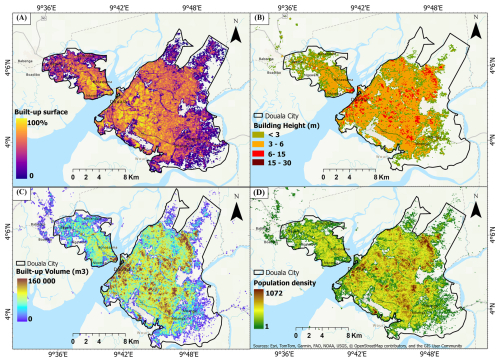

In addition to the large study area, we also performed a local analysis specifically for the urban city of Douala, where ArcGIS Pro 3.2 Spatial Analyst tools were used to extract, preprocess, analyse, and describe spatial patterns of specific LULC type, occupation, and morphological characteristics (urban landscape) from the GHSL data in the year 2020. The outcomes included a map of spatial built-up volume, spatial population density, spatial built-up height, spatial built-up surface, and morphological settlement zone.

LULC change analysis was performed to explore spatio-temporal patterns and shifts from 1992 to 2022. We used the LULC maps processed for 1992, 2007, 2015, 2017, and 2022 and focussed three different periods of 1992–2007, 2007–2015, and 2017–2022. Differences between LULC classes and indices across different periods were quantified using the ArcGIS Pro Raster Calculator tool. The output maps obtained highlight the areas where LULC changes between the initial and final years occurred.

3.4 Spatiotemporal correlation between land subsidence and land-use land cover changes

Land subsidence and LULC change are two significant environmental processes that are often interlinked, leading to various socioeconomic and ecological impacts (Minderhoud et al., 2018). Understanding the spatiotemporal correlation between these processes is crucial for sustainable urban planning and resource management. To investigate the relationship between the two variables in the DCL of Cameroon, we consider spatial patterns and temporal dynamics following the investigations of Minderhoud et al. (2018). We hypothesise that areas experiencing rapid LULC changes are often associated with noticeable land subsidence, and the timing of LULC change can influence the rate and extent of land subsidence. To investigate this hypothesis, we consider LULC classes intersecting with VLM pixels.

We quantified land subsidence and characterised the LULC patterns in the study area by applying spatial analysis tools in the GIS. We visualised the spatial distribution of land subsidence and land-use patterns from 1992 to 2022, and assessed the relationship between land subsidence, LULC, and urban city morphological characteristics statistically. Regression analysis was used to correlate the relationship between land subsidence rates and the various urban morphological characteristics from the GHSL. Correlation coefficients were explored to identify significant associations. Time-series graphs of land subsidence rates were then plotted for different LULC classes and morphological characteristics within the city of Douala.

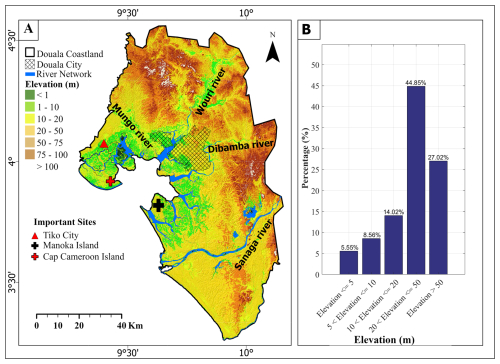

4.1 Elevation of the Douala Coastland

The Douala Coastland was delineated, covering a surface area of 2700 km2, with 4.5 % elevation below 5 m, 7 % elevation between 5 and 10 m, and 13 % elevation between 10 and 20 m above sea level (Fig. 4). Within this area, the city of Douala has key infrastructure, such as the Douala International Airport, the Douala seaport, and industrial plants. In addition, the study area includes the Douala Wetland area, Manoka Island, and Cap Cameroon Island, which appear to have very low elevations.

4.2 Vertical Land Motion in the Douala Coastland

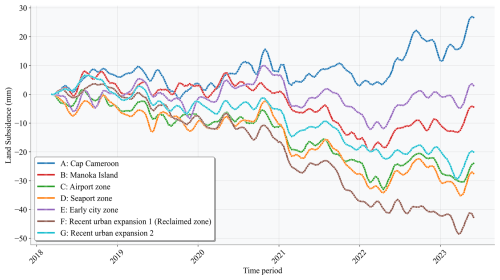

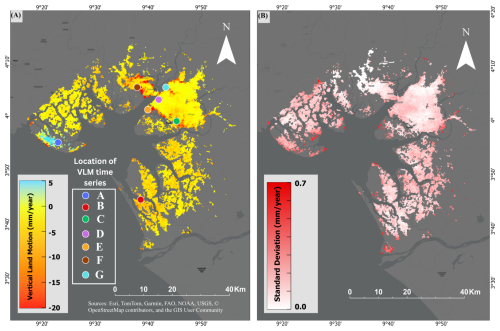

InSAR analysis revealed that the DCL is experiencing vertical land motion (VLM) rates ranging from −17.6 to 3.8 mm yr−1, with a median of −2.5 mm yr−1 and a mean of −2.7 mm yr−1 (p value < 0.0001 for 99 % confidence interval). The InSAR estimates are referenced to the IGS14 global reference frame and assumed to represents local VLM (Fig. 5). 97.9 % of the 68 680 scattering points in the study area showed land subsidence (VLM < 0 mm yr−1). Statistical analysis of the VLM further revealed that the remaining 2.1 % with positive vertical land motion rate lies between 0 and 4 mm yr−1 (p value < 0.0001 for 99 % confidence interval). A statistical description of the VLM rate range within the study area is shown in Fig. 5.

Figure 5VLM referenced to IGS1G and associated uncertainty derived from Sentinel-1 InSAR data over the Douala coastland. (A) Mean VLM rates (in mm yr−1), where negative values (yellow to red) indicate land subsidence and positive values (blue) indicate shallow uplift. (B) Standard deviation of the VLM estimates, illustrating the spatial variability of measurement uncertainty.

Across all seven selected sites in Douala in Fig. 6, land displacement between 2018 and 2023 reveals a clear spatial contrast between stable or uplifting natural/coastal zones and strongly subsiding reclaimed or heavily urbanized areas, as shown in Fig. 6. Cap Cameroon is the only location exhibiting sustained uplift, while Manoka Island and the early city zone show relatively minor subsidence, reflecting limited anthropogenic loading and more consolidated ground conditions. In contrast, the airport area, seaport zone, and especially the reclaimed urban expansion zones display progressive and substantial land subsidence in the most recently reclaimed area consistent with ongoing consolidation of fill material, heavy infrastructure loading, and groundwater variability.

4.3 Land-use and land cover changes in the Douala Coastland

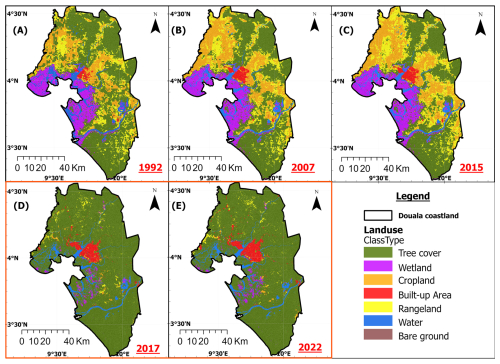

For the investigation period of 1992 to 2022, we document a constant decrease in the tree cover class, from 50.6 % of the total study area in 1992 to 38.7 % in 2015 (Fig. 7). High-resolution land-use data show a decrease in tree cover from 86.6 % in 2017 to 80.9 % in 2022. The reduction of forested areas occurs in favour of built-up, cropland, and rangeland areas as the respective LULC classes record substantial gains within the same period (Table 2). The cropland class increased from 14.4 % in 1992 to 20.6 % in 2015. Between 1992 and 2022, the built area class increased from 1 % to 4.7 %, reflecting the rapid urbanisation rate of Douala City, which has already been documented by previous studies (UN-Habitat, 2022).

Figure 7Land use and land cover (LULC) of Douala coastland in (A) 1992, (B) 2007, (C) 2015, (D) 2017, and (E) 2022. Panels (A)–(C) were extracted from the European Space Agency (ESA) Global Land Cover Maps, Version 2.0.7 datasets with a resolution of 300 m × 300 m. Panels (D)–(E) were extracted from the Sentinel-2 10-Meter LULC and Esri Land Cover (Esri) datasets. Tree cover definitions differ between ESA (A–C) and ESRI (D, E): it represents significant clusters of tall (∼ 15 m or higher) dense vegetation, typically with a closed or dense canopy, for the former, and areas dominated by trees with > 10 % tree cover for the latter.

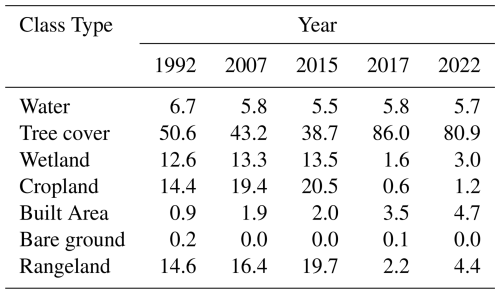

Table 2Distribution (in %) of Land use and land cover (LULC) classes for the years 1992, 2007, 2015, 2017, and 2022 in the Douala coastland. The percentage of classes cannot be summed to 100 because cloud-covered areas were excluded.

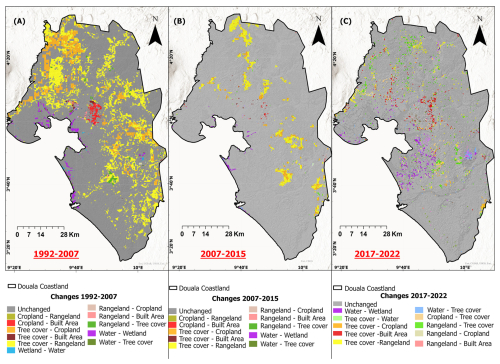

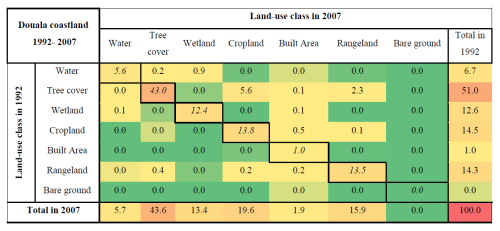

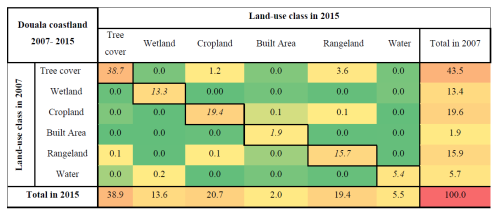

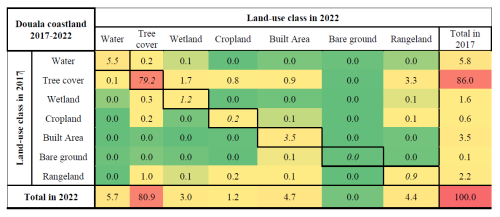

The outcomes of the land-use change analysis revealed that the main land cover classes undergoing significant dynamics included tree cover, cropland, rangeland, and built-up areas. Figure 8 shows the different LULC change maps for 1992–2007, 2007–2015, and 2017–2022. To further explore the different LULC changes and significance between 1992 and 2022, a LULC change matrix for each change interval was developed. The transition matrices for the periods 1992–2007 (Table 3), 2007–2015 (Table 4), and 2017–2022 (Table 5) provide quantitative changes between different classes.

Figure 8Land use and land cover (LULC) changes in Douala coastland over the following time periods: (A) 1992–2007, (B) 2007–2015, and (C) 2017–2022.

Table 3Land use and land cover (LULC) changes from 1992 to 2007 expressed as a percentage of the total study area, excluding cloud-covered regions. A color-coded scale from green to red is used to highlight null to large values, respectively. LULC remained unchanged in 89 % of the study area, see the values in italics located along the diagonal.

Table 4Land use and land cover (LULC) changes from 2007 to 2015 expressed as a percentage of the total study area, excluding cloud-covered regions. A color-coded scale from green to red is used to highlight null to large values, respectively. LULC remained unchanged in 94 % of the study area, see the values in italics located along the diagonal.

Table 5Land use and land cover (LULC) changes from 2017 to 2022 expressed as a percentage of the total study area, excluding cloud-covered regions. A color-coded scale from green to red is used to highlight null to large values, respectively. LULC remained unchanged in 90 % of the study area, see the values in italics located along the diagonal.

In Douala City, analyses of urban characteristics reveal a heterogeneous and dynamic city with varying population density, built-up height, and built-up surface (Fig. 9). In 2023, Douala City had an average spatial population density of 200 inhabitants per 10 000 m2 (ranging from 1 to 1072 inhabitants). At the same spatial scale, the average and median built-up surface percentages were 32 % and 35 % of the total built-up area, respectively. The mean and median building heights were 3 and 4 m, respectively. This shows that the level of building construction in terms of building height in Douala remained low. Combining these urban characteristics provides preliminary information on factors that could determine urban-differential soil consolidation.

4.4 Relation between land subsidence rate and LULC change

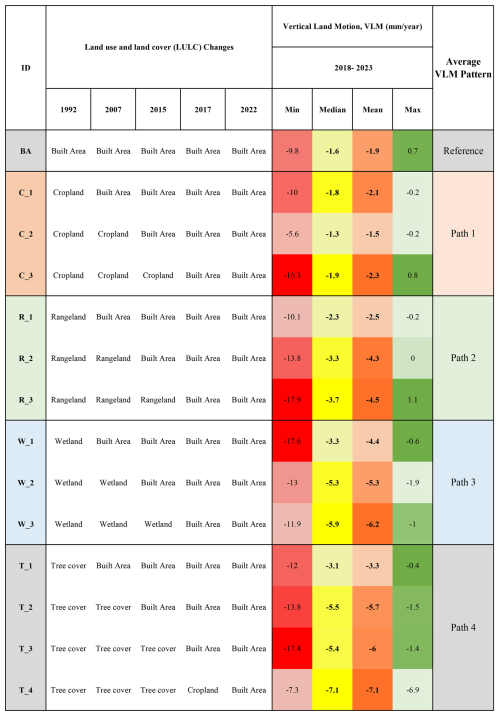

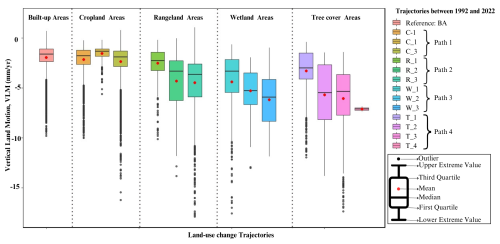

We investigated whether the documented LULC change patterns from 1992 to 2022 correlate with the measured land subsidence rates, considering four main categories of LULC change trajectories that potentially affect land subsidence. Each trajectory characterises the LULC change scenario occurring in a class from 1992 to 2022 (Table 6).

Table 6Statistical description of VLM with respect to various categories of LULC changes and urbanisation between 1992 and 2022. A color-coded intensity was used, independently in each column and within each path, to highlight land subsidence (negative VLM) amount. Darker colours indicate more severe land subsidence.

The different paths are as follow:

-

Path 1 (C_1 to C_3) represents cropland areas in 1992 were progressively converted into built-up areas;

-

Path 2 (R_1 to R_3) represents rangeland areas in 1992 were converted progressively into built-up areas;

-

Path 3 (W_1 to W_3) represents wetland areas in 1992 were progressively converted to built-up areas;

-

Path 4 (T_1 to T_4) represents the tree cover areas in 1992 were progressively converted into built-up areas.

We used as a reference the areas that were urbanised in 1992 and remained so throughout the investigated period. Inspection of Table 6 reveals that tree cover areas that recently (2017) changed to built-up areas are characterised by the highest mean and median rate of land subsidence. We observed similar results in all categories, except for the one in which the initial class in 1992 was cropland (Path 2), where no correlation between LULC change trajectories and subsidence rate was observed. In contrast, the areas that remained in the built-up area throughout 1992–2022 had the lowest mean and median subsidence rates (Fig. 10).

Figure 10Relationship between vertical land motion (based on InSAR for 2018–2023) and LULC change trajectories (1992–2022) as defined in Table 6. Built-up zones resulting from recent (i.e., over the period from 2015 to 2017) land-use conversion (trajectories C_3, W_3, and T3) show substantially higher land subsidence than zones urbanized earlier, indicating a correlation between built-up period and land subsidence.

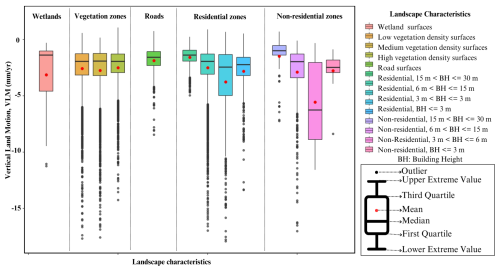

Further analysis was carried out to investigate the possible correlation between land subsidence and landscape within the urban city of Douala. The following landscape characteristics were considered: vegetation density, wetland surfaces, road surfaces, building functional use, and building height (Fig. 11). It appears that the mean subsidence rate in vegetated areas is relatively low at approximately 2.5 mm yr−1, irrespective of low-, medium-, and high-vegetation surfaces. The highest subsidence rate was observed in non-residential (industrial) zones, with buildings heights ranging from 3 to 6 m. This range corresponds to the mean and medium ranges of building height. In contrast, comparatively tall buildings in both residential and non-residential zones show very low subsidence, and the subsidence rate decreased with increasing building height.

5.1 Observed rates of vertical land motion

Our study reveals that the Douala Coastland experienced InSAR-estimated VLM ranging from −17.6 to 3.8 mm yr−1 between 2018 and 2023, resulting in a mean land subsidence rate of approximately 3.0 mm yr−1 (Fig. 5). A comparable value was associated with Douala based on the results obtained from a global study by Davydzenka et al. (2024), in which they implemented deep learning approaches combined with worldwide subsidence measurements to predict global land subsidence-susceptible areas based on 23 environmental parameters. Our results also align with the findings of Cian et al. (2019), who used InSAR to map land subsidence in 18 African coastal cities and determined that 17 out of 18 experienced subsidence, including Douala. This significant rate poses substantial threats to the region, exacerbating the impacts of sea-level rise, a critical concern for coastal communities worldwide (Nicholls et al., 2021). Furthermore, we find that 97.8 % of the coastal lowlands of Douala exhibit subsidence. Evidence of land subsidence in the Douala coastland is not an isolated case in the Gulf of Guinea, and similar investigations have highlighted the exposure of other coastal cities in Ghana (Avornyo et al., 2023; Brempong et al., 2023), Nigeria (Ohenhen and Shirzaei, 2022; Ikuemonisan et al., 2023), and Senegal (Cisse et al., 2024). This suggests that most urban cities along the Gulf of Guinea are undergoing subsidence, indicating an uncertain future for the Douala coastland and Gulf of Guinea in general. The occurrence of inundation and building collapse that has been observed in Douala (Tchamba and Bikoko, 2016) may be attributed to land subsidence, as reported in Nigeria by Ohenhen and Shirzaei (2022), who revealed that approximately 4000 buildings are exposed to a high to very high risk of long-term collapse in Lagos.

The combined effects of land subsidence and sea-level rise increase the vulnerability of coastal infrastructure, ecosystems, and populations, necessitating urgent attention and intervention strategies. Therefore, it is essential to provide a comprehensive understanding of land subsidence dynamics in the Douala coastland, examining the values in the context of other coastal cities worldwide that face similar challenges. Jakarta in Indonesia is one of the most severely affected cities by land subsidence, with contemporary rates reaching 10 cm yr−1 (Taftazani et al., 2022). This rapid subsidence can be primarily attributed to excessive groundwater extraction. In Italy, Venice faces subsidence rates of approximately 1–2 mm yr−1, compounded by rising sea levels (Teatini et al., 2005). Comparative analysis shows that the current coastland subsidence in Douala, averaging 3 mm yr−1, is significantly smaller than those experienced by other cities, such as Jakarta. However, the rate is comparable to the sea-level rise. This is particularly significant given the low elevation of Douala above sea level (Fig. 4; Kemgang et al., 2024).

Moreover, this study offers a snapshot of current VLM rates, which could change rapidly particularly under large-scale groundwater exploitation (Gambolati and Teatini, 2015; Minderhoud et al., 2020). The consequences of land subsidence for Douala may be far-reaching, affecting not only infrastructure and human settlements but also the health and sustainability of mangrove ecosystems, which are essential for coastal protection and biodiversity. Hence, further detailed investigations are required to elucidate the factors causing land subsidence in the Douala coastland, mitigate its occurrence, predict and prevent larger magnitudes in the future.

In addition to the uncertainty linked to other factors influencing land subsidence, we observed that 2.1 % of the SAR scattering points have positive vertical land motion with values ranging from 0 to 4 mm yr−1. Positive values of VLM can result from the effect of unaccounted horizontal motions in the north-south (NS) direction, which may entirely map onto the vertical signal due to limitations in the processing procedure. These scattering points are in a natural wetland area with little or no human activities. Another potential explanation is that the uplift results from sediment accumulation because of river-ocean interaction. Further investigations are needed to understand why this area shows uplift.

5.2 Landuse land cover (LULC) change

The Douala coastland has experienced significant LULC change dynamics (Fig. 7). An increasing trend was observed in areas allocated to croplands, built-up areas, wetlands, and rangelands, accompanied by a substantial decrease in tree cover (Table 2). The five-fold expansion of built-up areas is attributed to population growth and economic development, a phenomenon common in many rapidly growing and developing urban centers. These changes have far-reaching implications for environmental sustainability, ecosystem services, and the overall resilience of the region. The expansion of the anthropogenic footprint correlates with the study by Nfotabong-Atheull et al. (2013), which revealed that 39.9 % of mangrove forests disappeared in the peri-urban setting of Douala from 1974 to 2003, with a net loss of 22.1 % between 2003 and 2009 alone. Nfotabong-Atheull et al. (2013) highlighted a substantial increase in settlements (60 %), agricultural areas (16 %), non-mangrove areas (193.3 %), and open water (152.9 %) around Douala over a 35 year period from 1974 to 2009.

The transition matrices used to investigate the temporal dynamics between LULC classes revealed that the LULC change mechanism is not uniform over time. Between 1992 and 2007, there was a significant increase in cropland and rangeland, mainly because of a decrease in tree cover. The increase in the built-up area during the same interval was due to changes in three different classes: cropland, rangelands, and tree cover (Table 3). These changes were less significant between 2007 and 2015, which is probably also due to the shorter time range considered (eight years compared to 15 years). Tree cover areas remain the most dynamic class among the LULC classes. The major changes were from tree cover to rangeland and cropland. Between 2017 and 2022, when higher-resolution land cover datasets were used, the dynamics between classes were notably (Table 5). Approximately 6 % of the study area lost tree cover, and transformed the land into rangelands (3.3 %), wetlands (1.7 %), built areas (0.9 %), and croplands (0.8 %).

5.3 Land-use-driven land subsidence

Anthropogenic activities related to land-use practices, such as agricultural activities, groundwater extraction for irrigation, industries, and heavy infrastructure, directly influence subsidence (Galloway and Burbey, 2011; Gambolati and Teatini, 2021). We conducted a statistical analysis of the land-use change trajectories and subsidence rates within specific LULC classes to assess the correlation between the two processes. The results indicate that the mean and median land subsidence rates in each category, except cropland, increased with recent changes in the class to built-up areas. Relatively low subsidence was observed in the trajectories where the change to built-up areas occurred earlier. Indeed, areas that remained built-up from the beginning (1992) to the end (2022) of the investigated period exhibited the lowest average subsidence rate (1.9 mm yr−1), while areas that remained tree cover from 1992 to 2017, and subsequently changed to built-up areas over the last five years demonstrated the highest average subsidence rate (7.1 mm yr−1). This observation also applies to wetland and rangeland categories (Table 6 and Fig. 10). This trend can be attributed to the fact that recently urbanised areas are still undergoing consolidation due to the recent loading increase exerted by structures on the land surface. Moreover, tree root degradation during land-use change potentially contribute to land subsidence (Huning et al., 2024). Croplands, built-up areas, wetlands, and rangelands have notable implications for soil consolidation, which is a critical factor that affects the stability and sustainability of an area. Therefore, an appropriate land-use management mechanism must be considered as an adaptive or mitigating measure for controlling land subsidence.

With reference to the urban city of Douala, we investigated the influence of various urban morphological (landscape) characteristics, including wetlands, vegetation zones, roads, and residential and non-residential zones on land subsidence rates. The results revealed significant variations in land subsidence between the residential and non-residential zones. In residential zones, the highest subsidence rate was observed when building heights ranged between 3 and 6 m, whereas taller buildings exhibited relatively lower land subsidence. A similar trend was observed in the non-residential zones (Fig. 11). Taller buildings experienced less subsidence, potentially because of their deep foundations, which made them more stable and unaffected by shallow soil compaction, such as auto-compaction and lowering of the groundwater level in the phreatic aquifer system (Minderhoud et al., 2025). De Wit et al. (2021) reported similar observations in the Mekong Delta, as did Koster et al., (2018), Verberne et al., (2023), and Maoret et al., (2024) in cities in The Netherlands. Nevertheless, we acknowledge that the ability to distinguish deformation patterns between tall and low-rise buildings could be improved using a Persistent Scatterer InSAR (PS-InSAR) processing chain. The InSAR dataset employed in this study provides first-order insights into spatial deformation trends. However, the processing approach used introduces spatial smoothing, which may obscure localized variations in displacement, particularly in densely built-up areas. Future studies applying PS-InSAR methods with higher temporal and spatial sampling could therefore better resolve these fine-scale deformation differences and strengthen the interpretation of structural–geotechnical interactions across the urban landscape. In this context, this study provides a foundation for future detailed investigations of the vulnerability of the Douala coastland to the compound effects of environmental hazards associated with differential land subsidence and consequent relative sea-level rise.

In addition, groundwater pumping could significantly contribute to land subsidence especially in Douala, a rapidly growing coastal city with increasing groundwater demand for population and industrial activities. However, groundwater extraction data are scarce for the study area, limiting our possility to quantify aquifer depletion and its contribution to land subsidence. Nonetheless, observations from the GRACE (Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment) satellite mission indicate a progressive decline in terrestrial water storage between 2017 and 2023, suggesting ongoing groundwater loss at the regional scale. However, the GRACE data have a coarse spatial resolution (∼ 300–400 km), which constrains their capacity to resolve localized groundwater variations within the Douala coastal plain. As a result, while GRACE provides useful large-scale trends, it does not capture the fine-scale dynamics necessary to establish a direct spatial correspondence between subsidence patterns and groundwater extraction. This calls for the need to establish in-situ monitoring network for data collection.

We quantified vertical land motion in the Duala coastland between 2018 and 2023 using interferometric synthetic aperture radar from Sentinel-1 and investigated its relations to LULC change during the period 1992 to 2022. We found that VLM in the DCL ranges between −17.6 to 3.8 mm yr−1, while the DCL on average subsides 2.7 (median 2.5 mm yr−1). We documented a rapid, fivefold increase in urbanisation and that all contemporary urban areas experienced land subsidence, with the highest rates of 2.3 to 7.1 mm yr−1 occurring in non-residential zones with building heights between 3 and 6 m. In contrast, lower rates (1.9 to 4.4 mm yr−1) were found in older built-up areas, as most consolidation from building loads had occurred prior to the observation period. Subsidence rates of the DCL are inversely proportional to the time at which a particular LULC class changed into an urban area, highlighting the impact of the timing of LULC changes and urban expansion on present-day subsidence. The subsidence rates decreased with an increase in building height, suggesting the potential influence of foundation type on land subsidence as tall buildings are often associated with deeper foundations which likely makes these buildings less susceptible to shallow subsidence processes.

Land subsidence in the DCL presents a growing challenge, potentially driven by both natural and anthropogenic processes, analogous to the issues faced by other coastal cities globally. Over the past three decades, rapid urbanisation and LULC changes have likely contributed to substantial land subsidence rates, particularly in newly developed non-residential areas, specifically industrial zones and reclaimed lands. To address ongoing subsidence and its potential to exacerbate coastal erosion, relative sea-level rise and inundation, effective monitoring and mitigation strategies should be developed and implemented. However, it is imperative to acknowledge that multiple factors can cause land subsidence, and for the Douala coastland and city, more comprehensive studies are needed to thoroughly understand the ongoing and potential future land subsidence mechanisms. Investigating the effects of subsidence drivers such as groundwater extraction, soil compaction, building loading, and surface hydrology variation is essential to safeguard the rapid growth of urban zones on the Douala coastland and ensure their resilience against the adverse impacts of land subsidence, relative sea-level rise, and climate-related hazards such as flooding.

Inventory of images of the SAR frame datasets are found in the Supplement (Table S1).

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-26-551-2026-supplement.

The project was conceptualised by GCY, PT, and PJSM. The methodology was developed by GCY and LO with support from MS, PT, and PSJM. Visualisations and results interpretation were made by GCY, KS, PT and PSJM. The original draft was written by GCY. All authors contributed to editing and reviewing the manuscript.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. The authors bear the ultimate responsibility for providing appropriate place names. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

Philip S. J. Minderhoud is supported by the Dutch Science Foundation (NWO) under the Veni TTW 2022 programme with the project: “Drowning Deltas – Why deltas sink and what to do about it” (no. 20231). Katharina Seeger is supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG) under the Rising Sea and Sinking Land project (project no. 411257639).

The research was partially supported by the project “Coastal land subsidENce” in the GULF of Guinea (ENGULF) funded by the French Development Agency (AFD).

This paper was edited by Olivier Dewitte and reviewed by Kay Koster and one anonymous referee.

Avornyo Y. S., Addo, A. K., Teatini, P., Minderhoud, S. J. P., Woillez, M., Jayson-Quashigah, p., and Mahu, E.: A scoping review of coastal vulnerability, subsidence, and sea-level rise in Ghana: Assessments, knowledge gaps, and management implications, Quaternary Science Advances, 12, 100108, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.qsa.2023.100108, 2023.

Blackwell, E., Shirzaei, M., Ojha, C., and Werth, S.: Tracking California's sinking coast from space: Implications for relative sea-level rise, Science Advances, 6, 1–10, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aba4551, 2020.

Brempong, E. K., Almar, R., Angnuureng, D. B., Mattah, P. A. D., Avornyo, S. Y., Jayson-Quashigah, P. N., Appeaning Addo, K., Minderhoud, P., and Teatini, P.: Future fooding of the Volta Delta caused by sea-level rise and land subsidence, J. Coast. Conserv., 27, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11852-023-00952-0, 2023.

Candela, B. T. and Koster, K.: The many faces of anthropogenic subsidence, Science, 376, 1381–1382, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abn3676, 2022.

Cao, A., Esteban, M., Valenzuela, V. P. B., Onuki, M., Takagi, H., Thao, N. D., and Tsuchiya, N.: Future of Asian Deltaic Megacities under sea-level rise and land subsidence: Current adaptation pathways for Tokyo, Jakarta, Manila, and Ho Chi Minh City, Curr. Opin. Env. Sust., 50, 87–97, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jog.2023.101987, 2021.

Cian, F., Blasco, J. M. D., and Carrera, L.: Sentinel-1 for monitoring land subsidence of coastal cities in Africa using PSInSAR: A methodology based on the integration of SNAP and StaMPS, Geosciences, 9, 124, https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences9030124, 2019.

Cigna, F., Paranunzio, R., Bonì, R., and Teatini, P.: Present-day land subsidence risk in the metropolitan cities of Italy, Scientific Reports, 15, 34999, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18941-8, 2025.

Cisse, C. O. T., Brempong, E. K., Almar, R., Angnuureng, B. D., and Sy, B. A.: The potential impact of rising sea levels and subsidence on coastal flooding along the northern coast of Saint-Louis, Senegal, Preprints, 2024031468, https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints202403.1468.v1, 25 March 2024.

Costantini, M.: A novel phase unwrapping method based on network programming, IEEE T. Geosci. Remote, 36, 813–821, https://doi.org/10.1109/36.673674, 1998.

Costantini, M. and Rosen, P. A.: A generalized phase unwrapping approach for sparse data, in: Proceedings of the IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, IGARSS'99 (Cat. No.99CH36293), Hamburg, Germany, 1, 267–269, https://doi.org/10.1109/IGARSS.1999.773467, 1999.

Da Lio, C. and Tosi, L.: Land subsidence in the Friuli Venezia Giulia coastal plain, Italy: 1992–2010 results from SAR-based interferometry, Sci. Total Environ., 633, 752–764, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.03.244, 2018.

Dada, O., Almar, R., Morand, P., Bergsma, E. W. J., Angnuureng. B. D., and Minderhoud, S. J. P.: Future socioeconomic development along the West African coast forms a larger hazard than sea-level rise, Nature Communications Earth & Environment, 4, 1–12, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-023-00807-4, 2023.

Dada, O., Almar, R., and Morand, P.: Coastal vulnerability assessment of the West African coast to fooding and erosion, Scientific Reports, 14, 890, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-48612-5, 2024.

Davydzenka, T., Tahmasebi, P., and Shokri, N.: Unveiling the global extent of land subsidence: The sinking crisis, Geophys. Res. Lett., 51, e2023GL104497, https://doi.org/10.1029/2023GL104497, 2024.

De Wit, K., Lexmond, B. R., Stouthamer, E., Neussner, O., Dörr, N., Schenk, A., and Minderhoud, P. S. J.: Identifying causes of urban differential subsidence in the Vietnamese Mekong Delta by combining InSAR and field observations, Remote Sensing, 13, 189, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs13020189, 2021.

Dinar, A., Esteban, E., Calvo, E., Herrera, G., Teatini, P., Tomas, R., Li, Y., Ezquerro, P., and Albiac, J.: We lose ground: global assessment of land subsidence impact extent, Sci. Total Environ., 786, 147415, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.147415, 2021.

Ellison, C. E. and Zouh, I.: Vulnerability to climate change of mangroves: assessment from Cameroon, Central Africa, Biology, 1, 617–638, https://doi.org/10.3390/biology1030617, 2012.

Editor, A. M.: Addressing Flood Risk and Social Justice in Accra: Insights from Urban Expansion and Climate Change, African Researchers Magazine, ISSN: 2714-2787, https://www.africanresearchers.org/addressing-flood-risk-and- social-justice-in-accra-insights-from-urban-expansion-and-climate-change/ (last access: 20 January 2026), 5 February 2024.

ESA Land Cover CCI Project Team, and Defourny, P.: ESA Land Cover Climate Change Initiative (Land_Cover_cci): Global Land Cover Maps, Version 2.0.7, 18 October 2023, Centre for Environmental Data Analysis, https://catalogue.ceda.ac.uk/uuid/b382ebe6679d44b8b0e68ea4ef4b701c (last access: 30 November 2024), 2019.

European Commission (EC): GHSL Data Package 2023, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, JRC133256, https://doi.org/10.2760/098587, 2023.

Farr, G. T., Paul A. Rosen, A. P., Caro, E., Crippen, R., Duren, R., Hensley, S., Kobrick, M., Paller, M., Rodriguez, E., Roth, L., Seal, D., Shaffer, S., Shimada, J., Umland, J., Werner, M., Oskin, M., Burbank, D., and Alsdorf, D.: The Shuttle radar topography mission, Rev. Geophys., 45, RG2004, https://doi.org/10.1029/2005RG000183, 2007.

Ferretti, A., Prati, C., and Rocca, F.: Permanent scatterers in SAR interferometry, IEEE T. Geosci. Remote, 39, 8–20, https://doi.org/10.1109/36.898661, 2001.

Fossi, F. Y., Brenon, I., Pouvreau, N., Ferret, Y., Latapy, A., Onguene, R., Jombe, D., and Etame, J.: Exploring tidal dynamics in the Wouri estuary, Cameroon, Cont. Shelf Res., 259, 104982, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csr.2023.104982, 2023.

Fossi, F. Y., Pouvreau, N., Brenon, I., Onguene, R., and Etame, J.: Temporal (1948–2012) and Dynamic Evolution of the Wouri Estuary Coastline within the Gulf of Guinea, J. Mar. Sci. Eng., 7, 343, https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse7100343, 2019.

Franceschetti, G., Lanari, R., Franceschetti, G., and Lanari, R.: Synthetic Aperture Radar Processing, 1st edn., CRC Press, https://doi.org/10.1201/9780203737484, 1999.

Freire, S., MacManus, K., Pesaresi, M., Doxsey-Whitfield, E., and Mills, J.: Development of new open and free multi-temporal global population grids at 250 m resolution, Geospatial data in a changing world, Association of Geographic Information Laboratories in Europe (AGILE), JRC100523, 2016.

Galloway, D. L. and Burbey, T. J.: Review: Regional land subsidence accompanying groundwater extraction, Hydrogeol. J., 19, 1459–1486, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10040-011-0775-5, 2011.

Gambolati, G. and Teatini, P.: Geomechanics of subsurface water withdrawal and injection, Water Resour. Res., 51, 3922–3955, https://doi.org/10.1002/2014WR016841, 2015.

Gambolati, G. and Teatini, P.: Land subsidence and its mitigation, The Groundwater Project, Publ., Guelph, Ontario, Canada, https://doi.org/10.21083/978-1-77470-001-3, 2021.

Hammond, W. C., Blewitt, G., Kreemer, C., and Nerem, R. S.: GPS imaging of global vertical land motion for studies of sea level rise, J. Geophys. Res.-Sol. Ea., 126, e2021JB022355, https://doi.org/10.1029/2021JB022355, 2021.

Hanssen, R. F.: Radar interferometry: Data interpretation and error analysis, Springer, Dordrecht, https://doi.org/10.1007/0-306-47633-9, 2001.

Hauser, L., Boni, R., Minderhoud, P.-S.-J., Teatini, P., Woillez, M.-N., Almar, R., Avornyo, S.-Y., and Appeaning Addo, K.: A scoping study on coastal vulnerability to relative sea-level rise in the Gulf of Guinea, Éditions AFD, 42 pp., https://shs.cairn.info/journal-afd-research-papers-2023-283-page-1?lang=en (last access: 20 Janaury 2026), 2023.

Herrera-García, G., Ezquerro, P., Tomas, R., Béjar-Pizarro, M., López-Vinielles, J., Rossi, M., Mateos, R. M., CarreónFreyre, D., Lambert, J., Teatini, P., Cabral-Cano, E., Erkens, G., Galloway, D., Hung, W. C., Kakar, N., Sneed, M., Tosi, L., Wang, H., and Ye, S.: Mapping the global threat of land subsidence, Science, 371, 34–36, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abb8549, 2021.

Huning, L. S., Love, C. A., Anjileli, H., Vahedifard, F., Zhao, Y., Chaffe, P. L. B., Cooper, K., Alborzi, A., Pleitez, E., Martinez, A., Ashraf, S., Mallakpour, I., Moftakhari, H., and AghaKouchak, A.: Global land subsidence: Impact of climate extremes and humanactivities, Rev. Geophys., 62, e2023RG000817, https://doi.org/10.1029/2023RG000817, 2024.

Ideki, O. and Peace, N.: Analysis of Shoreline and Erosion Changes along the West African Coast from 1980 to 2020, Journal of Marine Science Research and Oceanography, 7, 1–8, https://doi.org/10.33140/JMSRO.07.01.02, 2024.

Ikuemonisan, F.-E., Ozebo, V.-C., Minderhoud, P.-S.-J., Teatini, P., and Woillez, M.-N.: A scoping review of the vulnerability of Nigeria's coastland to sea-level rise and the contribution of land subsidence, Éditions AFD, 34 pp., https://shs.cairn.info/journal-afd-research-papers-2023-284-page-1?lang=en (last access: 20 Janaury 2026), 2023.

Kemgang G. E., Nyberg B., Raj P. R., Bonaduce A., Abiodun J, B., and Johannessen M. O.: Sea level rise and coastal flooding risks in the Gulf of Guinea, Scientific Reports, 14, 29551, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80748-w, 2024.

Kenneth A. C.: Monitoring wetlands deterioration in the Cameroon coastal lowlands: implications for management, Proc. Earth Plan. Sc., 1, 1010–1015, 2009.

Koster, K., Stafleu, J., and Stouthamer, E.: Differential subsidence in the urbanised coastal-deltaic plain of the Netherlands, Neth. J. Geosci., 97, 215–227, https://doi.org/10.1017/njg.2018.11, 2018.

Lee, J.-C., and Shirzaei, M.: Novel algorithms for pair and pixel selection and atmospheric error correction in multi-temporal InSAR, Remote Sens. Environ., 286, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2022.113447, 2023.

Mantovani, J., Alcantara, E., Lima, T. A., and Simoes, S.: An assessment of ground subsidence from rock salt mining in Maceió (Northeast Brazil) from 2019 to 2023 using remotely sensed data, Environmental Challenges, 16, 100983, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envc.2024.100983, 2024.

Maoret, V., Candela, T., Van Dinther Y., Koster, K., Teatini, P., Van Wees, J. D., and Zoccarato, C.: Sinking cities: Towards prediction of subsidence-induced building damage, in: AGU Fall Meeting, 9–13 December 2024, https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2024AGUFMEP43A1276M/abstract (last access: 20 January 2026), 2024.

Mikhail, E. M. and Ackermann, F. E.: Observations and Least Squares method IEP, University Press of America, ISBN: 0-8191-2397-8, 1982.

Miller, M. M. and Shirzaei, M.: Spatiotemporal characterization of land subsidence and uplift in Phoenix using InSAR time series and wavelet transforms, J. Geophys. Res.-Sol. Ea., 120, 5822–5842, https://doi.org/10.1002/2015JB012017, 2015.

Miller, M. M. and Shirzaei, M.: Land subsidence in Houston correlated with flooding from Hurricane Harvey, Remote Sens. Environ., 225, 368–378, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2019.03.022, 2019.

Minderhoud, P., Shirzaei, M., and Teatini, P.: [Perspective] Combatting Relative Sea-Level Rise at a Global Scale: Presenting the International Panel on Land Subsidence (IPLS), Qeios, https://doi.org/10.32388/R5JEG2, 2024.

Minderhoud, P. S. J., Erkens, G., Pham, V. H., Bui, V. T., Erban, L., Kooi, H., and Stouthamer, E.: Impacts of 25 years of groundwater extraction on subsidence in the Mekong Delta, Vietnam, Environ. Res. Lett., 12, 064006, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aa7146, 2017.

Minderhoud, P. S. J., Coumou, L., Erban, L. E., Middelkoop, H., Stouthamer, E., and Addink, E. A.: The relation between land use and subsidence in the Vietnamese Mekong delta, Sci. Total Environ., 634, 715–726, 2018.

Minderhoud, P. S. J., Hlavacova, I., Kolomaznik, J., and Neussner, O.: Towards unraveling total subsidence of a mega-delta – the potential of new PS InSAR data for the Mekong delta, Proc. IAHS, 382, 327–332, https://doi.org/10.5194/piahs-382-327-2020, 2020.

Minderhoud, P. S. J., Shirzaei, M., and Teatini, P.: From InSAR-derived subsidence to relative sea-level rise – A call for rigor, Earth's Future, 13, e2024EF005539, https://doi.org/10.1029/2024EF005539, 2025.

NASA JPL: NASADEM Merged DEM Global 1 arc second V001, Open Topography [data set], https://doi.org/10.5069/G93T9FD9, 2021.

Nfotabong-Atheull, A., Din, N., and Dahdouh-Guebas, F.: Qualitative and Quantitative Characterization of Mangrove Vegetation Structure and Dynamics in a Peri-urban Setting of Douala (Cameroon): An Approach Using Air-Borne Imagery, Estuar. Coast., 36, 1181–1192, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12237-013-9638-8, 2013.

Nicholls, R. J., Lincke, D., Hinkel, J., Brown, S., Vafeidis, A. T., Meyssignac, B., Hanson, E. S., Merkens, J., and Fang, J.: A global analysis of subsidence, relative sea-level change, and coastal flood exposure, Nat. Clim. Change, 11, 338–342, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-021-01064-z, 2021.

Ohenhen, L., Shirzaei, M., Ojha, C., Sherpa, S. F., and Nicholls, R. J.: Disappearing cities on US coasts, Nature, 627, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07038-3, 2024.

Ohenhen, L. O. and Shirzaei, M.: Land subsidence hazard and building collapse risk in the coastal cities of Lagos, West Africa, Earth's Future, 10, https://doi.org/10.1029/2022EF003219, 2022.

Ohenhen, L. O., Shirzaei, M., Ojha, C., and Kirwan, M. L.: Hidden vulnerability of US Atlantic coast to sea-level rise due to vertical land motion, Nat. Commun., 14, 2038, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-37853-7, 2023.

Ondoa, G. A., Onguéné, R., Eyango, M. T., Duhaut, T., Mama, C., Angnuureng, D. B., and Almar, R.: Assessment of the Evolution of Cameroon Coastline: An Overview from 1986 to 2015, J. Coastal Res., Special Issue 81, 122–129, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26552360 (last access: 20 January 2026), 2018.

Parsons, T., Wu, P.-C., (Matt) Wei, M., and D'Hondt, S.: The weight of New York City: Possible contributions to subsidence from anthropogenic sources, Earth's Future, 11, e2022EF003465, https://doi.org/10.1029/2022EF003465, 2023.

Pesaresi, M. and Politis, P.: GHS-BUILT-C R2023A – GHS Settlement Characteristics, derived from Sentinel2 composite (2018) and other GHS R2023A data. European Commission, Joint Research Centre (JRC) [data set], https://doi.org/10.2905/3C60DDF6-0586-4190-854B-F6AA0EDC2A30, 2023a.

Pesaresi, M. and Politis, P.: GHS-BUILT-H R2023A – GHS building height derived from AW3D30, SRTM30, and Sentinel2 composite (2018), European Commission, Joint Research Centre (JRC), https://doi.org/10.2905/85005901-3A49-48DD-9D19-6261354F56FE, 2023b.

Pesaresi, M. and Politis, P.: GHS-BUILT-S R2023A – GHS built-up surface grid derived from Sentinel2 composite and Landsat, multi-temporal (1975–2030), European Commission, Joint Research Centre (JRC), https://doi.org/10.2905/9F06F36F-4B11-47EC-ABB0-4F8B7B1D72EA, 2023c.

Pesaresi, M. and Politis, P.: GHS-BUILT-V R2023A – GHS built-up volume grids derived from joint assessment of Sentinel2, Landsat, and global DEM data, multi-temporal (1975–2030), European Commission, Joint Research Centre (JRC), https://doi.org/10.2905/AB2F107A-03CD-47A3-85E5-139D8EC63283, 2023d.

Pesaresi, M., Corbane, C., Ren, C., and Edward, N.: Generalized vertical components of built-up areas from global Digital Elevation Models by multi-scale linear regression modelling, PLOS ONE, 16, e0244478, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0244478, 2021.

Schiavina, M., Freire, S., Carioli, A., and MacManus, K.: GHS-POP R2023A – GHS population grid multi-temporal (1975–2030), European Commission, Joint Research Centre (JRC), https://doi.org/10.2905/2FF68A52-5B5B-4A22-8F40-C41DA8332CFE, 2023.

Shirzaei, M.: A wavelet-based multi-temporal DInSAR algorithm for monitoring ground surface motion, IEEE Geosci. Remote S., 10, 456–460, https://doi.org/10.1109/LGRS.2012.2208935, 2013.

Shirzaei, M. and Bürgmann, R.: Topography-correlated atmospheric delay correction in radar interferometry using wavelet transforms, Geophys. Res. Lett., 39, 1–6, https://doi.org/10.1029/2011GL049971, 2012.

Shirzaei, M. and Walter, T. R.: Estimating the effect of satellite orbital error using wavelet-based robust regression applied to InSAR deformation data, IEEE T. Geosci. Remote, 49, 4600–4605, https://doi.org/10.1109/TGRS.2011.2143419, 2011.

Shirzaei, M., Freymueller, J., Törnqvist, T. E., Galloway, D. L., Dura, T., and Minderhoud, P. S. J.: Measuring, modelling and projecting coastal land subsidence, Nature Reviews Earth & Environment, 2, 40–58, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43017-020-00115-x, 2021.

Sikem, B.: In Cameroon, building inclusive climate change responses with technology, WeRobotics, https://werobotics.org/ blog/in-cameroon-building-inclusive-clima te-change-responses-with-technology (last access: 20 January 2026), 2021.

Taftazani, R., Kazama, S., and Takizawa, S.: Spatial Analysis of Groundwater Abstraction and Land Subsidence for Planning the Piped Water Supply in Jakarta, Indonesia, Water, 14, 3197, https://doi.org/10.3390/w14203197, 2022.

Tchamba, C. J. and Bikoko, L. J. T. G.: Failure and Collapse of Building Structures in the Cities of Yaoundé and Douala, Cameroon from 2010 to 2014, Modern Applied Science, 10, https://doi.org/10.5539/mas.v10n1p23, 2016.

Teatini, P., Tosi, L., Strozzi, T., Carbognin, L., Wegmüller, U., and Rizzetto, F.: Mapping regional land displacements in the Venice coastland by an integrated monitoring system, Remote Sens. Environ., 98, 403–413, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2005.08.002, 2005.

Thienen-Visser, K. V. and Fokker, A. P.: The future of subsidence modelling: compaction and subsidence due to gas depletion of the Groningen gas field in the Netherlands, Neth. J. Geosci., 96, s105–s116, https://doi.org/10.1017/njg.2017.10, 2017.

Tosi, L., Teatini, P., Strozzi, T., Carbognin, L., Brancolini, G., and Rizzetto, F.: Ground surface dynamics in the northern Adriatic coastland over the last two decades, Rend. Fis. Acc. Lincei, 21 (Suppl 1), S115–S129, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12210-010-0084-2, 2010.

Tzampoglou, P., Ilia, I., Karalis, K., Tsangaratos, P., Zhao, X., and Chen, W.: Selected Worldwide Cases of Land Subsidence Due to Groundwater Withdrawal, Water, 15, 1094, https://doi.org/10.3390/w15061094, 2023.

UN-Habitat: Urban Planning and Infrastructure in Migration Contexts: Douala, Cameroon – Spatial Profile, UN Human Settlements Programme, Kenya, COI: 20.500.12592/srtsv8, https://coilink.org/20.500.12592/srtsv8 (last access: 20 January 2026), 2022.

Venter, Z. S., Barton, D. N., Chakraborty, T., Simensen, T., and Singh, G.: Global 10 m Land Use Land Cover Datasets: A Comparison of Dynamic World, World Cover and Esri Land Cover, Remote Sensing, 14, 4101, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs14164101, 2022.

Verberne, M., Koster, K., Lourens, A., Gunnink, J., Candela, T., and Fokker, P. A.: Disentangling shallow subsidence sources by data assimilation in a reclaimed urbanized coastal plain, South Flevoland polder, the Netherlands, J. Geophys. Res.-Earth, 128, e2022JF007031, https://doi.org/10.1029/2022JF007031, 2023.

Verberne, M., Teatini, P., Koster, K., Fokker, P., and Zoccarato, C.: An integral approach using InSAR and data assimilation to disentangle and quantify multi-depth driven subsidence causes in the Ravenna coastland, Northern Italy, Geomechanics for Energy and the Environment, 43, 100710, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gete.2025.100710, 2025.

Wantim, M. N. and Ngeh Ngeh, H.: Impact of sea encroachment and tidal floods in coastal communities: case of Idabato subdivision, Bakassi Peninsula, Cameroon, J. Coast. Conserv., 29, 28, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11852-025-01113-1, 2025.

Wantim, M. N., Mokosa, W. A., Jitiz, L., and Ayonghe, S. N.: The utilisation of satellite imagery and community perceptions to assess the impacts of sea encroachment in the West Coast of Cameroon at Limbe, Journal of the Cameroon Academy of Sciences, 16, 211234, https://doi.org/10.4314/jcas.v16i3.3, 2021.

Werner, C., Wegmüller, U., Strozzi, T., and Wiesmann, A.: Gamma SAR and interferometric processing software, in: Proceedings of the ERS – Envisat Symposium, Gothenburg, Sweden, https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:28598270 (last access: 20 January 2026), 2000.

Wright, T. J., Parsons, B. E., and Lu, Z.: Towards mapping surface deformation in three dimensions using InSAR, Geophys. Res. Lett., 31, L01607, https://doi.org/10.1029/2003GL018827, 2004.

Wu, P.-C., Wei, M. (M.), and D'Hondt, S.: Subsidence in coastal cities throughout the world observed by InSAR, Geophys. Res. Lett., 49, e2022GL098477, https://doi.org/10.1029/2022GL098477, 2022.

Zhou, C., Gong, H., Chen, B., Li, X., Li, J., Wang, X., Gao, M., Si, Y., Guo, L., Shi, M., and Duan, G.: Quantifying the contribution of multiple factors to land subsidence in the Beijing Plain, China with machine learning technology, Geomorphology, 335, 48–61, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2019.03.017, 2019.

Zhou, C., Gong, H., Chen, B., Gao, M., Cao, Q., Cao, J., Duan, L., Zuo, J., and Shi, M.: Land subsidence response to different land use types and water resource utilization in Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei, China, Remote Sensing, 12, 457, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs12030457, 2020.

Zhu, L., Gong, H. L., Li, X. J., Wang, R., Chen, B. B., Dai, Z. X., and Teatini, P.: Land subsidence due to groundwater withdrawal in northern Beijing Plain, China, Eng. Geol., 193, 243–255, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2015.04.020, 2015.

Zoccarato, C., Minderhoud, P. S. J., and Teatini, P.: The role of sedimentation and natural compaction in a prograding delta: insights from the mega Mekong delta, Vietnam, Science Report, 8, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-29734-7, 2018.