the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Brief Communication: Rejuvenating and strengthening the science–policy interface required to implement the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction

Here we reflect on progress towards the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction, focusing on the health of the global-level science–policy interface. Reflecting on the 2025 Global Platform for Disaster Reduction, we identify weaknesses in mechanisms for scientific engagement. While the Sendai Framework highlights science as foundational to risk reduction, engagement remains limited by ad hoc structures and unclear processes. This article proposes three steps to revitalise the science–policy interface, emphasising inclusivity, synthesising scholarly contributions to support knowledge sharing, and dedicated thematic forums. Strengthening this science–policy interface is essential to realising the Sendai Framework's objectives through to and beyond 2030.

- Article

(1070 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

Endorsed by the United Nations General Assembly in 2015, the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction aims to achieve the substantial reduction of disaster-related losses and risks across all sectors and scales (UNDRR, 2015). Central to this intergovernmental agreement is the recognition of science as a critical foundation for understanding, assessing, and mitigating disaster risk (Aitsi-Selmi et al., 2016). A decade on from its agreement, the global disaster risk reduction community convened in Geneva, Switzerland, in June 2025 to assess progress, identify challenges, and propose strategies to accelerate implementation. This article reflects on that gathering, raises concerns about a potential weakening of key aspects of the science–policy interface underpinning the Framework's goals, and considers the actions necessary to ensure the scientific community (in all its rich diversity) plays a full role in informing and shaping work to and beyond 2030.

Disasters are complex and interdisciplinary challenges, requiring contributions from diverse actors. While nation states have a primary responsibility to reduce disaster risk (UNDRR, 2015), the Sendai Framework encourages a multi-stakeholder approach, with a clear role for the science and technological community (Pearson and Pelling, 2015; Aitsi-Selmi et al., 2016). This includes those working in the natural, environmental, social, economic, health, and engineering disciplines (UNISDR, 2009), including a broad spectrum of geoscientists (e.g., geologists, seismologists, volcanologists, hydrologists, meteorologists, physical geographers, geomorphologists and others), from a wide range of sectors (e.g., academia, industry, the public sector, and civil society) and countries. The science and technology community are key contributors – alongside others – to understanding risk and its components, as well as designing and delivering effective risk reduction mechanisms (Gill and Bullough, 2017; Smith and Bricker, 2021; Gill et al., 2021). A potential weakening of the flow of knowledge between the scientific and policy-making communities or from local science–policy interfaces to global dialogues, or mechanisms which exclude certain voices, has potential implications on the effectiveness of risk reduction.

For the work of natural hazard scientists to be useful, useable, and used in the context of risk reduction, a strong science–policy interface is, therefore, required. Such interfaces exist at multiple scales (from local to global) and are defined as “social processes which encompass relations between scientists and other actors in the policy process, and which allow for exchanges, co-evolution, and joint construction of knowledge with the aim of enriching decision-making” (van der Hove, 2007). The aim of science–policy interfaces is to deliver decisions (both within and beyond the public policy domain) that are well-informed about the nature of the problem and the potential solution space, informed by the best available evidence (Van Enst et al., 2014). While they may be characterised as both a process or an organisation (Van Enst et al., 2014), typical shared requirements of an effective science–policy interface include (a) scientific networks engaging in a transparent manner, (b) genuine interdisciplinary interactions between social and natural sciences, and (c) scientists exercising their responsibility as knowledge holders and technology developers (van der Hove, 2007).

Science-policy interfaces can operate at multiple levels or scales and include both bottom-up and top-down approaches (van der Hove, 2007). An example of a bottom-up approach is a scientist working with local government, with their findings then shared with national or international agencies. An example of a top-down approach is the UN putting out a “call for evidence” with scientists responding to this call. Different scales and approaches do not exist in isolation but rather support and reinforce each other, to deliver a thriving and inclusive science–policy interface. A top-down approach on its own may reduce the likelihood of evidence-informed policy at a local level, but similarly a lack of scientific engagement at the intergovernmental (or global-level) may result in UN agendas and frameworks excluding or misrepresenting the priorities and perspectives of scientists.

In exploring mechanisms by which the scientific community can feed into intergovernmental processes regarding disaster risk reduction, we do not disregard the importance of other types or scales of science–policy interaction. Similarly, by focusing on this aspect of the science–policy interface, we are not implying that discourses on other topics (e.g., transdisciplinary science, co-development with local policy communities, science-society interactions) are less relevant. The objective of this brief communication is to reflect on the 2025 Global Platform for Disaster Reduction, a major intergovernmental policy event, and what this tells us about the science–policy interface to encourage the broad science community to consider how we respond to the challenge of a weakening voice of science within this process. In the following sections we look at how science is presented in the Sendai Framework and subsequent reporting and mechanisms for scientists to engage (Sect. 2), potential weaknesses in the existing science–policy interface supporting this Framework, as witnessed at the 2025 Global Platform for Disaster Risk Reduction (Sect. 3), and recommendations for strengthening this process (Sect. 4). Concluding remarks are set out in Sect. 5.

The Sendai Frameworks articulates a role for the scientific community in delivering its objectives, with several specific references to “science” throughout:

-

A guiding principle of the Framework emphasises the need for “easily accessible, up-to-date, comprehensible, science-based, non-sensitive risk information, complemented by traditional knowledge” (UNDRR, 2015, Clause 19g, emphasis added).

-

At a regional and global level, there is an agreed action to “enhance the scientific and technical work on disaster risk reduction and its mobilization through the coordination of existing networks and scientific research institutions at all levels and in all regions, with the support of the UNDRR Scientific and Technical Advisory Group” (UNDRR, 2015, Clause 25g, emphasis added).

-

At national and local levels, agreed actions include supporting and facilitating science–policy interfaces for effective decision-making in disaster risk management (UNDRR, 2015, Clauses 24h, 36b, emphasis added).

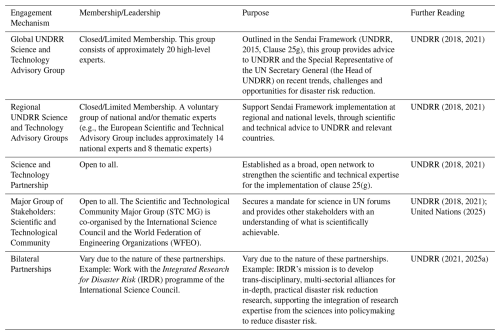

In this context, mobilisation of the scientific community is suggested to assist in enhancing methods and standards for risk assessments and disaster risk modelling, encourage effective data use, help identify gaps and priorities in research and technology, and support the integration of scientific knowledge into decision-making processes (UNDRR, 2015). In the decade since the agreement of the Sendai Framework, science has been emphasised repeatedly to be instrumental in delivering effective disaster risk reduction. This was a key message of the mid-term review of the Sendai Framework, with the associated political declaration noting the “instrumental and cross-cutting role of science, technology and innovation in strengthening the effectiveness and efficiency of disaster resilience-building” while also encouraging more application of science to support and accelerate the implementation of the Sendai Framework (United Nations, 2023, Clause 41). Taken together, these statements highlight a recognition that science is a central pillar to shaping and implementing effective disaster risk reduction strategies. The UNDRR Partnership and Stakeholder Engagement Strategy agrees and outlines some primary mechanisms by which scientists can engage with the Sendai Framework monitoring and implementation process (UNDRR, 2021), as summarised in Table 1.

The mechanisms in Table 1 exist alongside the rich diversity of ways that individual scientists and scientific institutions can support implementation of the Sendai Framework through, for example, research that helps to understand risk. But while expectations of what scientists can offer to strengthen risk reduction are high (United Nations, 2023, Clause 41) and mechanisms for the community to engage at the science–policy interface are supposedly rich (see Table 1), evidence suggests that there is considerable scope to rejuvenate and improve the structures and systems that facilitate dialogue with scientists at the intergovernmental level. Of the different mechanisms listed in Table 1, several appear to be stagnant, lack clear guidance on how to participate, or are implemented in an ad hoc manner that hinders effective and inclusive participation. For example, at the time of writing, online information about the Global UNDRR Science and Technology Advisory Group (STAG) includes a list of members from 2017–2018 and terms of reference last updated in 2018. Online information about the European regional STAG lacks clarity regarding their terms of reference and when and how members are appointed. These challenges were not unforeseen. At the outset of the Sendai Framework implementation period, Carabine (2015) emphasised the need for the UNDRR STAG to be as open, inclusive and participatory as possible, highlighting concerns about the lack of clarity on how the STAG would be governed and structured. Alongside these challenges, there is currently no online information about how to join the Science and Technology Partnership, and (as outlined in Sect. 3) limited opportunities by the Scientific and Technological Community Major Group to support engagement in Sendai-related processes. While online information may not capture the full activity of a particular mechanism, it is used here as a measure of both accessibility and transparency.

If these opportunities for engagement are lacking – or not open to all – we lose an important opportunity for excellent scientific research in Kenya (for example) to be profiled on a global stage and adopted by other regions and countries. Unclear guidance on how advisory groups function and recruit members may result in perspectives from the globally diverse scientific community not being embedded into the advice provided to UNDRR (and other UN-level agencies). While scientific insights may be brought into discussions via other stakeholders, supported by science–policy interfaces at local and national levels, direct participation at the global level strengthens the science–policy interface. The approach to stakeholder engagement by the UN (through self-organised “Major Groups”) is designed to ensure direct participation of a range of stakeholder groups (from indigenous communities to business and industry, to NGOs), contributing to transparency and representative decision making.

The Global Platform for Disaster Risk Reduction is the UN General Assembly–recognised multi-stakeholder forum for reviewing progress on the implementation of the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction, identifying gaps, and making recommendations to further accelerate action towards its stated objectives (UNDRR, 2025b). The 8th Session of the Global Platform took place in June 2025, co-organised by UNDRR and the Government of Switzerland.

As a multi-stakeholder forum, one would expect engagement by a wide range of stakeholders, including the science and technology community. The forum gathered more than 3600 people from 177 countries, with approximately 10 % of these self-identifying as being part of a science and technology stakeholder group. If examining the convened sessions and oral and written statements by other stakeholder groups (e.g., parliamentarians), one can see a strong emphasis on the vital role of the scientific community in delivering the Sendai Framework. For example, the Government of the Philippines shared a report from the Asia Pacific Ministerial Conference on Disaster Risk Reduction that noted the need to increase “science, technology and innovation, to help transform huge amounts of data into actionable information for local communities” (Government of the Philippines, 2025). However, in the run up to this key event (just 5 years from 2030) there was no truly open coordination with the wider community by the Scientific and Technological Community Major Group, to feed into the full range of topics being discussed. During the Global Platform, there was no visible presence or reporting from the Global STAG and no statements delivered or placed online by the Scientific and Technological Community Major Group coordinators. In contrast, civil society was well represented at the 2025 Global Platform, with participation from individual grassroots organisations, networks, and coordinating groups. The coordination among these was evident, inclusive and effective. This is evidenced by the fact key messages and advocacy points by the Global Network of Civil Society Organisations for Disaster Reduction were adopted by the co-chairs and included in their event summary, the Geneva Call for Disaster Risk Reduction (GNDR, 2025; UNDRR, 2025c).

Individual scientists and scientific organisations did engage and contribute at the Global Platform. For example, a statement was shared by Geology (now Geoscience) for Global Development, co-produced with the American Geophysical Union, European Geosciences Union, Geological Society of London, International Union of Geodesy and Geophysics, and Global Volcano Risk Alliance. Some key scientific reports were also published during the Forum (e.g., the latest revisions to the UNDRR and ISC (2025) Hazard Information Profiles, that involved liaising with a large and diverse group of scientists. These examples differ from – but also demonstrate the huge benefits of – a coordinated, inclusive approach to policy engagement. While there is a responsibility on Major Group coordinators and UNDRR (as the initiator of the STAG and Science and Technology Partnership), there is also a responsibility on scientific publishers, organisations, professional societies and unions, as well as individual scientists to reflect on what more they can do to support a strong, effective science–policy interface.

Given the importance of the scientific community to advancing the Sendai Framework (and disaster risk reduction more broadly) and recognising a potential weakening of the science–policy interface required to help facilitate engagement by and with scientists (set out in Sect. 3), action is needed to reverse this. Here are three ideas (and seven recommendations) on how we can leverage the potential of the scientific community to support global disaster risk reduction efforts:

4.1 A refreshed, truly inclusive mechanism for the representation of science in the multi-stakeholder, multilateral processes aligned with the Sendai Framework

The science and technology community can learn from other stakeholder groups (e.g., civil society) to develop and maintain a structure that facilitates ongoing dialogue between the global science community and other disaster risk reduction stakeholders. Examples of specific recommendations on how to deliver this include:

- a.

Readily accessible information about the (existing) independent coordinating mechanism for the science and technology community in the Sendai Framework, including information about the mechanism, ways of engaging, and the groups coordinating it and how to contact them.. This aligns with the approach followed by other UN processes (e.g., the Sustainable Development Goals) (United Nations, 2025).

- b.

Dedicated focal points (individuals or organisations) within international unions and other scientific organisations, to support a bidirectional flow of information into and out of that coordinating mechanism. The International Science Council could develop a set of “focal point” role descriptions relating to multi-lateral processes (including, but not limited to, the Sendai Framework) that are distributed to member societies (e.g., the International Union of Geological Sciences, IUGS) to support them to establish these roles in their structures. Focal points can then share with the membership of these organisations any opportunities for engagement (e.g., calls for panel members, open consultations) as well as coordinate surveys of the membership to identify key priorities, perspectives, and case studies.

- c.

A commitment to open and inclusive practice by the Major Group of Stakeholders: Scientific and Technological Community (Table 1), ensuring meaningful opportunities to contribute to calls for evidence, the shaping of policy positions, and the design and delivery of activities at (for example) Regional and Global Platforms. Typical activities at these Platforms include spoken interventions (on behalf of the stakeholder group), side events, and position papers released before and during the event.

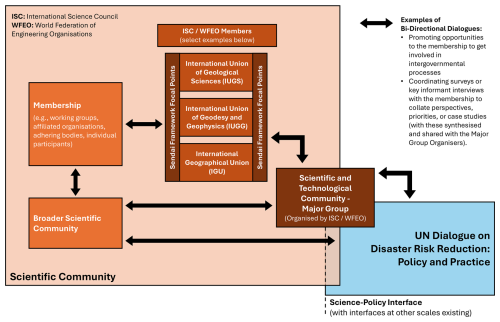

Coordinating organisations are resource-limited, and the temporal proximity of the UN Ocean Conference and High-Level Political Forum to the 2025 Global Platform may explain the limited engagement of the Scientific and Technological Community Major Group in the latter. Some of the recommendations above are not resource-intensive (e.g., improved information on a website, to ensure transparency). Others may require some resourcing but can be implemented in a scalable way to reflect resource limitations. For example, a low-resource approach could be for organisations such as the IUGS to include a simple form in their e-newsletter asking for members' top priorities in terms of advancing disaster risk reduction, with a synthesis of these shared in a written submission to the International Science Council in advance of the next Global Platform. If more resources were available, the IUGS could then also write to all adhering bodies and affiliated organisations and ask for evidenced case studies of effective solutions, turning this into a full, illustrated report disseminated to national governments in advance of the Global Platform. The recommendations in Sect. 4.1 provide ways for major group coordinators to leverage the expertise of others to support their work and opens the engagement process to a wider group of scientists than those able to attend events in person. Figure 1 illustrates the approach set out in these recommendations and illustrates how the work and resources indicated in the next Section (4.2), often involving a local-scale science–policy interface, could be shared at an international level to inform dialogue around disaster risk reduction.

Figure 1A refreshed approach to increase participation in the existing Scientific and Technological Major Group to inform and support implementation of the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction (and any successor frameworks). In this adaptation of the currently existing model, members of the International Science Council and World Federation of Engineering Organisations (the coordinators of this Major Group) are encouraged to nominate Sendai Framework Focal Points (either individuals or organisations) to support the bi-directional flow of knowledge and strengthen the Science–Policy Interface. For example, Focal Points may coordinate a survey to capture key priorities of their members (both affiliated groups and individual scientists), and share this with the International Science Council, who in turn embed these into their written statements or oral presentations delivered at intergovernmental forums. Direct engagement and participation in Major Group activities by individual member organisations and the broader scientific community must also still be possible.

4.2 Proactive collation and sharing of learning, case studies, priorities, and perspectives

There are many large gatherings of scientists around the world, with the results of millions of hours of work being presented. These conferences, along with the scholarship captured in scientific journals and technical reports, represent a significant body of evidence that can inform disaster risk reduction actions at all scales. There is an unrealised potential to bring together and synthesise this learning into reports that support other stakeholders, such as those working in policy settings. Examples of specific recommendations on how to deliver this include:

- a.

Thematic (e.g., early warning, risk communication) and geographically specific (e.g., Central America, West Africa) reports capturing emerging priorities and innovations that are presented at scientific conferences.

- b.

Major scientific journals with a risk reduction focus (e.g., Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences) appointing a dedicated editorial role that focuses on promoting access to and understanding of the journal's content by other disaster risk reduction stakeholders, to maximise impact and learning from scholarly work.

4.3 A regular thematic platform focused on science, technology, and innovation, with the outcome document feeding into the Global Platform

Regional Platforms (a geographically limited version of the UNDRR Global Platform on Disaster Risk Reduction) offer a potential model for focused discussion that is then integrated into the Global Platform. The annual UN Forum on Science, Technology, and Innovation for the SDGs, which feeds into the High-Level Political Forum on Sustainable Development, sets a welcome precedent for a thematic forum contributing to intergovernmental processes. A three-day Science and Technology Conference organised by UNDRR in 2016 was pivotal in mobilising the scientific community to help implement the Sendai Framework. A regular thematic platform could help to galvanise the scientific community and ensure their perspectives are captured and fed into the intergovernmental Global Platform. Examples of specific recommendations on how to deliver this include:

- a.

Convening a dedicated meeting to bring together the broad scientific and technological communities, as part of the range of events preceding and feeding into the shaping of a Global Platform (alternative options would be to have these feed into every other Global Platform, or to incorporate a Sendai focused day into the annual UN Forum on Science, Technology, and Innovation for the SDGs).

- b.

Preparing a formal outcome document, capturing the key points of the thematic platform, for discussion at the Global Platform.

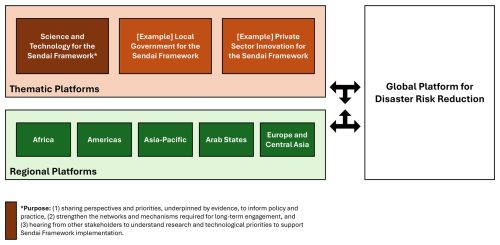

Figure 2 sets out the approach set out in this recommendation and illustrates how the work and resources indicated in Sect. 4.2 could be fed into the Global Platform dialogue.

Figure 2Thematic Platforms to inform the UNDRR Global Platform for Disaster Risk Reduction. Modelled on existing Regional Platforms, and the success of the 2016 Science and Technology Conference on the implementation of the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030, a set of thematic platforms could open up new opportunities to mobilise the scientific community and capture and share learning, case studies, priorities, and perspectives.

While mechanisms have been established to support the science–policy interface required to support implementation of the Sendai Framework – work is needed to refresh these in the next 5 years as we seek to deliver action, and as dialogues commence on the post-2030 agenda. The recommendations made in this article are not exhaustive, and do not capture all aspects of the science–policy interface (from local to global) but they offer some initial perspectives on what can be done to improve inclusive engagement at an intergovernmental level, strengthen the bi-directional flow of knowledge between scientists and policy makers, and generate more impact from scholarly work (ensuring a better bridge between local and global science–policy interfaces). Other actions will be needed, and the wider ecosystem of scientific organisations and individuals are encouraged to reflect on what they perceive to be current weaknesses and what they can offer to address these.

The primary goal of the Sendai Framework is the substantial reduction of disaster risk and losses in lives, livelihoods and health and in the economic, physical, social, cultural and environmental assets of persons, businesses, communities and countries (UNDRR, 2015). Reducing disaster risk is key to advancing sustainable development objectives. As we work towards these ambitions, we must recognise that structures and mechanisms can both hinder and catalyse progress. Achievements to-date can be lost or their full potential never realised, if we don't capture, share, and build on good practice and ensure improved access to scientific understanding, data, tools, and products. Rejuvenating and strengthening the science–policy interface required to deliver the Sendai Framework should be an urgent priority if we are to secure the progress expected – and needed – by communities around the world.

No data sets were used in this article.

The author has declared that there are no competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. The authors bear the ultimate responsibility for providing appropriate place names. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

The author thanks two anonymous reviewers and the NHESS handling editor (Sven Fuchs) for their constructive engagement with this manuscript.

Attendance at the 2025 Global Platform for Disaster Risk Reduction was supported by the Lloyd's Register Foundation Grant TWRP\100012 (improving household preparedness in multi-hazard contexts). Work on this concept note by Joel C. Gill was funded by Cardiff University's Harmonised Impact Acceleration Account Strategic Impact Fund (H-IAA SIF). Geoscience for Global Development are supported financially by the International Union of Geological Sciences (IUGS).

This paper was edited by Sven Fuchs and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Aitsi-Selmi, A., Murray, V., Wannous, C., Dickinson, C., Johnston, D., Kawasaki, A., Stevance, A. S., and Yeung, T.: Reflections on a science and technology agenda for 21st century disaster risk reduction: Based on the scientific content of the 2016 UNISDR science and technology conference on the implementation of the Sendai framework for disaster risk reduction 2015–2030, Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci., 7, 1–29, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13753-016-0081-x, 2016.

Carabine, E.: Revitalising evidence-based policy for the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030: lessons from existing international science partnerships, PLoS Curr., 7, https://doi.org/10.1371/currents.dis.aaab45b2b4106307ae2168a485e03b8a, 2015.

Gill, J. C. and Bullough, F.: Geoscience engagement in global development frameworks, Ann. Geophys., 60, https://doi.org/10.4401/ag-7460, 2017.

Gill, J. C., Taylor, F. E., Duncan, M. J., Mohadjer, S., Budimir, M., Mdala, H., and Bukachi, V.: Invited Perspective: Building sustainable and resilient communities–Recommended actions for natural hazard scientists, Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci., 21, 187–202, https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-21-187-2021, 2021.

GNDR: GNDR's participation at the UN Global Platform for Disaster Risk Reduction, https://www.gndr.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/GNDR-GPDRR-2025-Report.pdf (last access: 16 December 2025), 2025.

Government of the Philippines: Statement delivered to the multi-stakeholder plenary “regional progress on implementation of the Sendai Framework” at the 2025 Global Platform, https://globalplatform.undrr.org/media/107436/download?startDownload=20250723 (last access: 16 December 2025), 2025.

Pearson, L. and Pelling, M.: The UN Sendai framework for disaster risk reduction 2015–2030: Negotiation process and prospects for science and practice, J. Extreme Events, 2, 1571001, https://doi.org/10.1142/S2345737615710013, 2015.

Smith, M. and Bricker, S.: Sustainable cities and communities, in: Geosciences and the Sustainable Development Goals, Springer International Publishing, Cham, 259–282, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-38815-7_11, 2021.

UNDRR: Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030, https://www.undrr.org/publication/sendai-framework-disaster-risk-reduction-2015-2030 (last access: 16 December 2025), 2015.

UNDRR: Terms of Reference – Science and Technology Advisory Group (STAG), https://www.undrr.org/implementing-sendai-framework-partners-and-stakeholders/science-and-technology-action-group (last access: 16 December 2025), 2018.

UNDRR: Partnership and Stakeholder Engagement Strategy, https://www.undrr.org/media/91259/download?startDownload=20250703 (last access: 16 December 2025), 2021.

UNDRR: Science and Technology Community, https://www.undrr.org/implementing-sendai-framework/partners-and-stakeholders/science-and-technology-community (last access: 16 December 2025), 2025a.

UNDRR: Global Platform for Disaster Risk Reduction, https://globalplatform.undrr.org/2025/about-gp (last access: 16 December 2025), 2025b.

UNDRR: The Geneva Call for Disaster Risk Reduction: The Co-Chairs' Summary of the Global Platform, https://www.undrr.org/news/geneva-call-disaster-risk-reduction-co-chairs-summary-global-platform (last access: 16 December 2025), 2025c.

UNDRR and ISC: Update of the UNDRR-ISC Hazard Information Profiles, https://www.undrr.org/publication/2025-update-undrr-isc-hazard-information-profiles-hips (last access: 16 December 2025), 2025.

UNISDR: International Strategy for Disaster Risk Reduction Scientific and Technical Committee, Reducing Disaster Risks through Science: Issues and Actions, UNISDR, Geneva, 32 pp., https://www.unisdr.org/files/11543_STCReportlibrary.pdf (last access: 16 December 2025), 2009.

United Nations: Political declaration of the high-level meeting on the midterm review of the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030, A/RES/77/289, https://www.undrr.org/publication/political-declaration-high-level-meeting-midterm-review-sendai-framework-disaster-risk (last access: 16 December 2025), 2023.

United Nations: Scientific and Technological Community, https://hlpf.un.org/mgos/scientific-and-technological-community (last access: 16 December 2025), 2025.

Van den Hove, S.: A rationale for science–policy interfaces, Futures, 39, 807–826, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2006.12.004, 2007.

Van Enst, W. I., Driessen, P. P., and Runhaar, H. A.: Towards productive science–policy interfaces: a research agenda, J. Environ. Assess. Policy Manag., 16, 1450007, https://doi.org/10.1142/S1464333214500070, 2014.

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Science and the Sendai Framework

- Reflections on the 2025 Global Platform for Disaster Risk Reduction

- Recommendations to Strengthen the Science–Policy Interface

- Concluding Remarks

- Data availability

- Competing interests

- Disclaimer

- Acknowledgements

- Financial support

- Review statement

- References

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Science and the Sendai Framework

- Reflections on the 2025 Global Platform for Disaster Risk Reduction

- Recommendations to Strengthen the Science–Policy Interface

- Concluding Remarks

- Data availability

- Competing interests

- Disclaimer

- Acknowledgements

- Financial support

- Review statement

- References