the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Tsunamigenic potential of unstable masses in the Gulf of Pozzuoli, Campi Flegrei, Italy

Filippo Zaniboni

Luigi Sabino

Cesare Angeli

Martina Zanetti

Alberto Armigliato

Campi Flegrei, one of the most monitored and studied volcanic areas in the world, has recently attracted significant attention due to the reactivation of its peculiar activity, consisting of small earthquakes, geothermal phenomena and slow subsidence/rapid uplift cycles, known as bradyseism. While much of the research and of the attention focuses on potential eruptions or other volcanic-related activities, the potential hazard posed by gravitational instabilities has received little consideration. The interaction of the destabilized masses with water can trigger tsunamis, potentially affecting the whole coastline of the Gulf of Pozzuoli, which lies above the Campi Flegrei caldera. Moving from the limited available geomorphological studies of the area, a set of four landslide-tsunami scenarios (one subaerial and three submarine sources) are reconstructed. These are simulated through a sequence of numerical codes, accounting for all the phases of the tsunami process, providing insights into the distribution of tsunami energy and identifying the most affected coastal stretches. Additionally, the study explores the influence of dispersion effects in the tsunami propagation and the occurrence of resonance effects in some minor inlets of the Gulf, emphasizing the importance of accounting for complex and non-linear coastal processes when treating landslide-generated tsunamis.

- Article

(14409 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

The recent strengthening of the Campi Flegrei activity has raised many concerns about the potential impacts of volcanic-related manifestations on local population and infrastructures. The caldera, located in correspondence of an extremely densely inhabited area in the surroundings of Naples (South Italy), is one of the most active and dangerous in the world. The study of the hazard correlated to the Campi Flegrei activity, concerning the tephra dispersal in case of eruption, has been already treated in the scientific literature (Selva et al., 2021). On this basis, a National Civil Protection plan has been realized in case of emergency (https://mappe.protezionecivile.gov.it/en/risks-maps-and-dashboards/national-planning-phlegraean-fields/, last access: 20 January 2026). Other considered potential hazards linked to the eruption of the Campi Flegrei caldera are pyroclastic flows (Neri et al., 2015), phreatic explosions (Mayer et al., 2016) and mud flows generated by the interaction between the ash ejected from the volcano and the rain (Isaia et al., 2021). Earthquakes are frequent, though characterized by low magnitude. As an example, according to the September 2025 INGV – Osservatorio Vesuviano bulletin (https://www.ov.ingv.it/index.php/monitoraggio-e-infrastrutture/bollettini-web/bollettini-web-flegrei/anno-2025-5/1886-bollettinoweb-cf-2025-settembre/file, last access: 20 January 2026), 423 events have been recorded during the month. Almost 88 % of these had magnitude lower than 1, four exceeded Md=2.0 and the maximum was 4.0.

The interaction of volcanic activity with the sea and the consequent generation of tsunamis received some attention as well: the work by Paris et al. (2019) tested the effects of submarine volcanic explosions in the Gulf of Pozzuoli by means of numerical scenarios and a Probabilistic Tsunami Hazard Analysis (PTHA) methodology. Grezio et al. (2020) attempted a comprehensive approach including earthquakes, submarine landslides and volcanic explosions as potential sources for tsunami generation affecting the Gulf of Naples, implementing them into a PTHA providing hazard curves for different localities along the coasts.

Specifically, gravitational collapses are one of the least considered potential sources of natural hazards in the area. Volcanic activity at Campi Flegrei can induce instability both in the short term, through seismic shaking, and in the long term, due to slope steepening associated with the caldera uplift. The scenarios considered in Grezio et al. (2020) were purely synthetic, without evaluation of geological and morphological evidence, of the sliding dynamics and of possible hydrodynamic effects during the tsunami propagation. In occasion of the 30 June 2025 earthquake (magnitude 4.6), a rock mass detached from the coastal ridge of Punta Pennata, in Bacoli, at the western end of the Gulf of Pozzuoli, provoking some local sea level oscillations (https://en.cronachedellacampania.it/2025/06/terremoto-crollata-una-parete-di-punta-pennata-a-bacoli/, last access: 20 January 2026), and putting in the spotlight such type of phenomenon.

This work aims to fill these gaps, by assessing the tsunamigenic potential of local submarine and subaerial landslides, evaluating the tsunami distribution patterns and the respective impact on the coasts, at the scale of the Gulf of Pozzuoli basin. The masses generating the waves are selected based on a worst-case credible approach (see e.g. Tonini et al., 2011; Zaniboni and Armigliato, 2026), which relies upon the present morphology and upon the existing knowledge of the mass transport processes in the area. The tsunami hazard is then assessed through a set of numerical codes, already tested and applied in many other landslide-tsunami cases. This investigation has been preliminarily performed and reported in Sabino (2024): here it is extended including the role of dispersion in the tsunami propagation, since it can have significant influence in the impact of the waves on the coasts.

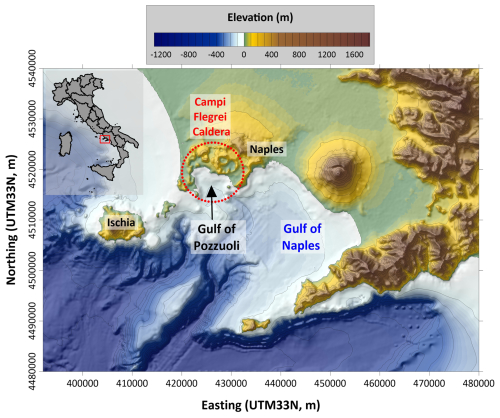

Campi Flegrei volcano

Campi Flegrei is a complex volcanic system with a history spanning at least the last 78 000 years (Perrotta et al., 2006), characterized by intense unrest episodes involving ground deformation and seismicity (de Natale et al., 2006), together with explosive eruptions and variable vent locations (Bevilacqua et al., 2015). Seismic studies have revealed a large magmatic sill at depth, potentially connected to the surface through deep fractures (Zollo et al., 2008). The heart of Campi Flegrei is the vast caldera, an almost circular structure with a diameter of about 10 km (marked by the red dashed line in Fig. 1) involving the western districts of Naples in its subaerial expression, with a total potentially affected population of more than 360 000, living in the cities of Pozzuoli, Bagnoli and Bacoli. The submarine part of the caldera is covered by the Gulf of Pozzuoli, a small, shallow water sub-basin of the wider Gulf of Naples. The landscape of this area has been shaped by several volcanic events: the caldera was formed by a catastrophic volcanic explosion that occurred approximately 39 000 years ago. This event, an eruption of 100–200 km3 of rock called “Ignimbrite Campana” (Rosi et al., 1983; Perrotta et al., 2006), shaped the region's topography, creating a unique landscape characterized by hills, fumaroles, and hot springs. At the centre of the caldera rises the Solfatara crater, a focal point for the volcanic and geothermal activity in the area. Historical reports from Roman times reveal a general trend of slow subsidence (rate of about 1–2 cm yr−1), alternated with occasional episodes of faster uplift (Di Vito et al., 2016; De Vivo et al., 2020), a peculiar behaviour that took the name of “bradyseism”. Soil subsidence can lead to coastal flooding, as testified by the submerged park of Baia, where Roman houses and constructions are still visible now at 6–8 m depth. The last significant eruption of Campi Flegrei caldera occurred in 1538, with 0.03 km3 of erupted products that gave rise to the hill of Monte Nuovo in one single night (De Vivo et al., 2001). After that, the floor of the caldera underwent slow and regular subsidence. In more recent times, some episodes of uplift interrupted this phase: 74 cm in 1950–1952, 159 cm in 1970–1972 and 178 cm in 1982–1984 (Del Gaudio et al., 2010), resulting in a maximum rise of about 3.5 m of the ground in the city of Pozzuoli, with shallow micro-seismicity recorded in response to fluid movement episodes.

Figure 1Morphological map of the Gulf of Naples (South Italy). The red-dashed circle delimits approximately the Campi Flegrei caldera, involving a subaerial part (west of Naples) and a submarine portion (Gulf of Pozzuoli).

At present, bradyseism, which resumed in mid-2023, is still ongoing. The GNSS network has measured, since January 2024, an uplift of more than 33 cm in some stations (see https://www.ov.ingv.it/index.php/monitoraggio-e-infrastrutture/bollettini-web, last access: 26 January 2026). Seismic activity has been intensifying during this period, although most of the events are characterized by low magnitudes (about 90 % of the events had magnitudes less than 1.0, see https://www.ov.ingv.it/index.php/monitoraggio-e-infrastrutture/bollettini-tutti/bollett-mensili-cf, last access: 26 January 2026), with maximum depths around 4 km, predominantly concentrated within the first 2 km (Danesi et al., 2024).

The investigation on the tsunami hazard in the Gulf of Pozzuoli associated to the Campi Flegrei activity, triggering potential instabilities interacting with water, is here performed through numerical methods, which in turn implement approaches that are described in this section. An initial necessary premise concerns the importance of considering the dispersive effects in landslide-tsunami simulations, a task that is usually underestimated but whose effects could be relevant in the analysis of the tsunami impact on the coast.

2.1 Landslide-tsunamis and dispersive effects

Tsunamis are oscillations induced by a perturbation of the equilibrium state involving the whole water body, which can be produced by sudden changes in the sea bottom (earthquakes, submarine landslides, underwater volcanic explosions) or upon the sea surface (subaerial landslides, atmospheric perturbations, cosmogenic tsunamis).

In general, in hydrodynamics, each wave is subject to the dispersion relation, linking the phase velocity c to the wave number k (or to its inverse, the wavelength λ): the smaller is the second (i.e., the bigger is the wavelength), the higher is the first. In short, longer oscillations are faster than shorter ones (for a general overview about this topic see for example Saito, 2019).

A tsunami can be considered generally as a non-monochromatic wave, resulting from the superposition of different components, each characterized by a specific wavelength, then with its own velocity. When λ is much bigger than the water depth h of the involved basin, the hydrodynamic equations can be significantly simplified by means of the shallow-water (SW) approach, in which tsunamis are treated as “long-waves”. This is generally valid for waves generated by earthquakes, since the source has dimensions that is usually much bigger than the typical depth of the sea. When the tsunami trigger is provided by other phenomena, such as landslides, SW is known to neglect important hydrodynamic effects, such as dispersion, that can affect significantly the wave propagation and impact on the coast. It is generally agreed that SW is considered proper when the ratio is bigger than 20, while for lower values (i.e., for “shorter” waves) a more sophisticated and higher-order version of the hydrodynamic equations should be considered, as for example the Boussinesq approximation (hereafter accounted for as non-hydrostatic approach, NH).

A quantification of the dispersive effects on the tsunami propagation was attempted in Glimsdal et al. (2013). A rearrangement of the considerations found in that work leads to the estimation of the ratio between distance and initial signal wavelength for which the dispersion becomes relevant and cannot be neglected anymore. Calling this (non-dimensional) dispersion distance as D, the expression is:

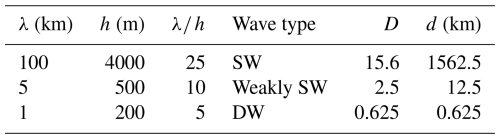

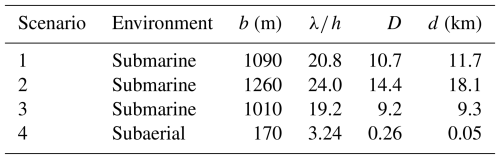

For “long waves”, then, and D≈10: dispersive effects manifest at least at a distance ten times the initial wavelength. Table 1 reports some typical values for wavelengths and water basin depths found respectively for: earthquake-tsunamis (first line), for which generally SW approach is applicable; submarine landslide tsunamis (second line) for which SW is valid only on limited domains; subaerial landslide tsunamis (third line), which can be considered in general as deep-water (DW) waves, for which the NH approach is more suitable.

Table 1Examples of waves and of computing of respective dispersion distance. λ: initial wavelength; h: water depth; D: dispersion distance, computed by Eq. (1); d: distance for which dispersion effects become predominant ().

In general, we can see that dispersion affects every tsunami, also the “longer” ones, but it manifests only on very long distances, where probably the perturbation itself has already been damped by other propagation effects. Neglecting dispersion means that the different components of the tsunami travel all together and impact the coast at the same time; conversely, when considering it, the longer components travel much faster than the shorter ones. This provokes an “unpacking” of the tsunami, that is much more evident and effective with increasing distance from the source: in general, then, neglecting dispersion causes an overestimation of the tsunami effects.

2.2 Overview on numerical techniques

Landslide-generated tsunamis are highly complex processes. Assessing their impact on the coast through numerical simulations requires numerous approximations and assumptions. The approach adopted here divides the entire process into distinct phases: (i) the landslide motion, (ii) the transfer of energy from the mass to the water, (iii) tsunami propagation, and (iv) the wave's impact on the coast. Each phase is treated independently, and back-interactions are not considered: for example, the mass-water interaction, where the wave's propagation can alter the water column and influence the dynamics of the landslide on the seafloor up to 20 % (Harbitz et al., 2006), is neglected in this study, since those effects do not affect considerably the tsunami propagation. The phases are addressed sequentially, with the output of one stage serving as the input for the next.

2.2.1 Landslide motion

The movement of the mass along the seafloor triggers the tsunami. Unlike earthquake-generated tsunamis, where the source process can be considered instantaneous relative to the wave's propagation (at least as a first approximation), landslide-tsunamis exhibit a generation phase that evolves in comparable time with the ensuing waves. Thus, it is essential to accurately describe the mass dynamics and the evolution of shape changes. This is achieved using the numerical code UBO-BLOCK (see detailed description in Tinti et al., 1997), which divides the sliding mass into interacting portions. The equation governing the centre of mass (CoM) motion is determined by the forces acting on the mass: gravity, buoyancy, basal friction, surface drag, and an internal interaction force accounting for energy dissipation due to deformation. The last element is crucial, since it accounts for shape changes of the mass during its motion, a factor that influences also the wave generation and that can't be neglected: it is found, in fact, that rigid block approximation for landslide collapses produces an overestimation of the generated tsunamis (see for example the review in Yavari-Ramshe and Ataje-Ashtiani, 2016). The resulting time-series of geometric and dynamic quantities describing the landslide motion is then generated. Applications of UBO-BLOCK to landslide-tsunami events can be retrieved in Triantafillou et al. (2020), Zaniboni et al. (2021), Gallotti et al. (2021, 2023), Gasperini et al. (2022), Zaniboni et al. (2024) and in the references therein.

2.2.2 Tsunamigenic impulse

The next step involves assessing the perturbation to the water column caused by the sliding motion along the seafloor. This disturbance provides the dynamic forcing term for the wave propagation equations, which are not instantaneous but evolve over time. The change in the seafloor due to the landslide is interpolated onto the tsunami grid nodes, with a filter applied to local sea depths that suppresses high frequencies. These tasks are handled by the intermediate code UBO-TSUIMP (details in Tinti et al., 2006).

2.2.3 Tsunami propagation and coastal impact

The final two phases are simulated using the JAGURS code, which solves the fluid dynamics equations using finite difference methods. Tsunami propagation can be modelled using either the shallow-water (SW) equations or a more sophisticated approach that accounts for vertical variations in hydrodynamic quantities, implementing for example the Boussinesq model (NH). The non-hydrostatic method allows the code to capture dispersion effects, which are crucial for landslide-generated tsunamis, as described in Sect. “Campi Flegrei volcano”. JAGURS supports simulations over computational grids with varying resolutions (using a nested grid approach) and can model coastal inundation. It is also optimized for parallel computing with MPI and OpenMPI coding, enabling the simulation of dispersive effects over large computational domains (see Baba et al., 2015, for further description). While JAGURS is widely used for earthquake-generated tsunamis (Ren et al., 2021; Ehara et al., 2023), for landslide-generated events it requires some adaptations, due to the nature of the phenomenon itself. As previously mentioned, the tsunamigenic impulse for landslide-tsunamis is not instantaneous: then, it must be provided to the code as a sequence of single impulses, one for each time step describing the landslide motion along the sea bottom and producing the perturbation.

2.3 Computational grid

The numerical codes applied here require as input a equally-spaced computational grid, whose definition and assembling needs a compromise among different aspects: the detailed description of the morphology, mainly for the coastal areas, requires a huge number of nodes, that on the contrary needs to be limited basing on the computational resources available. Additionally, landslide-tsunamis are known to affect limited domains, due to the dispersive effects characterizing their oscillations that produce a rapid damping of their amplitude. In the specific case studied here, the morphology of the seabed suggests that the mass instabilities induced by the Campi Flegrei activity have typically small volumes, producing waves that will presumably travel modest distances, with reduced consequences on the coasts. Under all these considerations, the selected tsunami computational domain covers the Pozzuoli Gulf for an area of 12 km×11 km approximately, with a spatial step of 20 m and a total number of nodes of about 340 000. Raw data have been retrieved from the database MaGIC for the coastline and the bathymetry (DPC, 2023), and from the database Tinitaly (Tarquini et al., 2023) as concerns the topography.

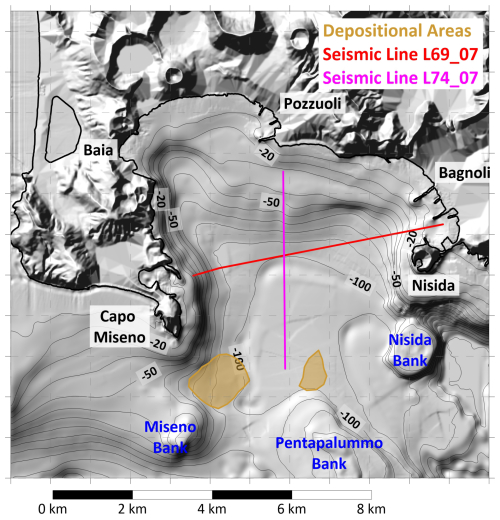

From the morphology, that can be inferred from the general map in Fig. 1 and with more detail in Fig. 2, it is possible to infer some insights about landslide triggering and the ensuing tsunami propagation: (i) the underwater slopes are in general quite gentle, inhibiting high initial acceleration of the sliding masses, one of the most important factors in tsunami genesis (e.g., Lovholt et al., 2015). Only the areas close to the Gulf's mouth opposite sides, i.e., Capo Miseno on the west and Nisida Bank on the east (see Fig. 2 for toponyms), show steep submarine gradients. (ii) the coastal slope is generally flat, favoring water ingression and tsunami penetration; only the two abovementioned areas (Capo Miseno and Nisida) are characterized by steep coastal profiles, that can also produce rapidly moving collapses into the water. (iii) the sea is rather shallow within the Gulf, with maximum depth reaching about 100 m, while it deepens eastward and southward. This will have consequences on the wave propagation in the basin, since, as we have seen, the sea depth deeply influences the tsunami behaviour during the propagation. (iv) finally, but not less importantly, at this level of detail it is possible to represent the main piers and harbour structures (well visible at Pozzuoli and Bagnoli, Fig. 2), which influence the wave propagation with local effects, such as for example multiple reflections and resonance.

Figure 2Morphological map of the Gulf of Pozzuoli. Black labels denote the main coastal toponyms, blue ones the submarine volcanic edifices. The brown contours mark the recognized depositional areas; the red and magenta lines report the seismic line called L69_07 and L74_07 respectively. Such features are retrieved from Aiello et al. (2012).

2.4 Mass instabilities in the Gulf of Pozzuoli and landslide scenarios

The evaluation of the landslide-tsunami hazard in the Gulf of Pozzuoli requires, as a first step, to identify the sources, i.e., masses that have the potential to generate waves, both in submarine and in the subaerial environments. This investigation is here performed through a scenario approach, meaning that those collapses are hypothesized starting from geological and morphological evidence, studying their signatures (scars, slopes, deposits) and the ensuing tsunamis evaluated through the numerical routine previously illustrated. The assumption is that such scenarios represent the range of possible and credible worst events occurring in the area, following the approach called Worst-case Credible Tsunami Hazard Assessment (WCTHA, see Tonini et al., 2011 and Zaniboni and Armigliato, 2026, for description and application), which is suitable to phenomena like landslide-tsunamis, where neither recurrence time are defined nor extensive catalogues of events are available, contrary to the most adopted approach in tsunami science (PTHA, see e.g. Behrens et al., 2021). In the specific case of the Gulf of Pozzuoli, we will see that, lacking detailed bathymetric surveys of the seabed specifically devoted to map and describe such occurrences, the WCTHA is not fully applicable: evidence of past collapses is scarce and a general pattern of the potential mass movements is not defined. Moreover, in a context like the Campi Flegrei, bradiseismic activity, morphology and trigger can change rapidly in time, defining new threshold for “worst-case credible” scenarios. The scenarios that have been individuated, then, must not be considered as detailed reconstruction of past events, but as representative of categories of collapse events that potentially occurred, whose potential hazard is here evaluated through numerical simulations. In the following, as a first step, the search for mass collapse traces in the Gulf of Pozzuoli within the scientific literature is reported.

Recent magnetic surveys in the larger Gulf of Naples evidenced the presence of consistent deposits on the seabed, testifying an intense mass transport activity in the whole area (de Ritis et al., 2024), that could have probably generated tsunamis affecting the area of interest of this study. The focus, though, is here centred on local sources, i.e., potential landslides triggered by the seismic shaking related to the Campi Flegrei caldera, then along the slopes (submarine and subaerial) in the Gulf of Pozzuoli area. As already mentioned, this is a small, shallow water basin, whose detailed stratigraphic and morphological features have been revealed by high-resolution seismic and bathymetric surveys (Aiello et al., 2012; Somma et al., 2016). The area is characterized by numerous seismic units, both volcanic and sedimentary, and by a complex tectonic setting related to the intense Campi Flegrei volcanic activity. The northern part of the basin shows an inner shelf with maximum depth of 50 m, deepening to 100 m with gentle slopes and delimited by a belt of submarine volcanic edifices: starting from East, they are called Miseno Bank, Pentapalummo Bank and Nisida Bank (see Fig. 2). The morphological investigations have revealed the presence of deposits in the deeper and flat part of the Gulf, especially around Miseno Bank and in the central part of the basin (areas in light brown, Fig. 2; Aiello et al., 2012). The seismic sections reported in the same publication evidence the presence of buried deposits with peculiar characteristics, which have been characterized and denoted as paleo-landslides. Figure 2 reports the profiles along which they have been found: one lies along the transect L69_07 (in red), extending in the E–W direction and showing a potential deposit close to Nisida; the second refers to the line L74_07 (in magenta), running in the N–S direction from Pozzuoli. The morphological evidence close to Miseno Bank and the two buried deposits found in the seismic profiles will be taken as the basis for the submarine landslide scenarios adopted for this investigation.

Regarding subaerial sliding, a comprehensive geodatabase (CAFLAG) documents 2302 landslide events from 1828–2017, most of which consists of rock falls affecting volcanic slopes and rainfall-induced slides in pyroclastic deposits (Esposito and Matano, 2023). Landslide hazards affect over 15 % of the subaerial Campi Flegrei area, with varying risk levels among towns (Calcaterra and di Martire, 2022). The events of interest here are the ones potentially interacting with water: the candidates are then restricted to collapses along the coastline that are not simple rockfalls (surely generating high waves but only locally, dissipating quickly, as in the case of 30 June 2025, previously cited), but more complex body collapses involving a coherent mass impacting the water and moving along the seafloor.

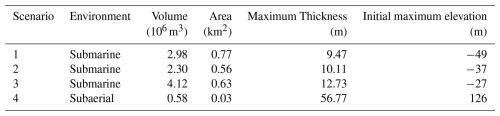

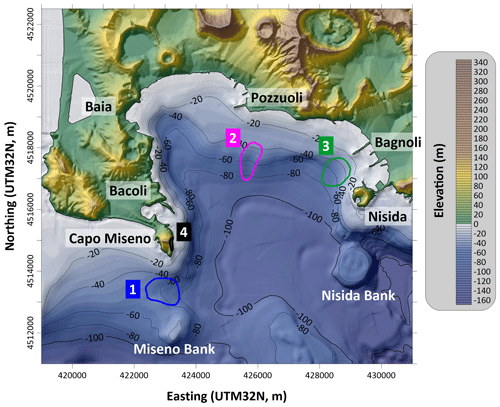

Based on all these considerations, a set of four landslide scenarios has been arranged for the numerical simulations. Table 2 summarizes their geomorphological characteristics (volume, area, maximum thickness and initial elevation), while Fig. 3 reports the position of the initial masses for each case. Three of them are submarine and cover different positions over the Gulf of Pozzuoli, while the fourth is subaerial.

Figure 3Location of the initial bodies for the four landslide scenarios hypothesized: in blue, Scenario 1, between Capo Miseno and Miseno Bank; in magenta, Scenario 2, south of Pozzuoli; in green, Scenario 3, offshore Bagnoli; in black, Scenario 4, along the cliffs of Capo Miseno.

Scenario 1 (blue contour in Fig. 3) is located just south of Capo Miseno, at the western end of the Gulf, and has been reconstructed starting from the deposit shown in brown in Fig. 2. The hypothesis is that the mass detached from the seafloor depression between Capo Miseno and the Miseno Bank, with the constraint to obtain a volume comparable to the observed deposit at the toe of the slope: since an accurate estimate of this does not exist, a conservative approach has been adopted basing on the hypothesized boundary and on a reasonable thickness distribution, basing on the seafloor morphology. The volume obtained for this scenario is of almost 3 million m3.

Scenario 2 (in magenta, Fig. 3) lies in the central part of the Gulf and has been built based on the buried paleo-landslide recognized in the seismic profile just south of Pozzuoli (magenta line, Fig. 2). Its morphology is quite arbitrary, since scarce information exist on this hypothesis. Adopting again a conservative approach, this has been taken similar to Scenario 1, with volume and initial area slightly smaller, though its shape is more elongated in the sliding direction.

Scenario 3 (green boundary, Fig. 3) is placed in the eastern part of the basin, and recalls a buried paleo-landslide as well, relative to another seismic transect (E–W from Nisida, see Fig. 2, red line). This scenario shows a slightly larger volume (around 4 million m3), a slightly larger initial thickness and moves from shallower water: all these elements suggest a likely higher capability of triggering relevant waves.

Scenario 4 (in black, Fig. 3) is the only subaerial scenario, and is located along the coastal cliffs of Capo Miseno, at the western end of the Gulf of Pozzuoli. It has been chosen by morphological considerations and recalling the 30 June 2025 rockfall, assuming the large coastal subaerial scar of the eastern flank of Capo Miseno – still visible now – originated from a single, sudden collapse. The resulting scenario is quite different from the other cases: volume much smaller (around half million m3) and much larger initial thickness (maximum of more than 50 m).

As mentioned previously, accurate characterisation of geotechnical properties and rheological behaviour of these masses are not available. Since these factors can significantly influence both the landslide dynamics and the ensuing tsunami, this study adopts a set of reasonable assumptions, common to all involved cases. The slides are considered predominantly translational, allowing for elongation during motion and descent toward the deeper, central part of the basin. An exception is Scenario 1, where the presence of a hypothesized depositional area acts as a constraint on the model parameters regulating the dynamics. Although these assumptions are simplified and approximate, and each case would deserve more accurate reconstruction and characterization, they are considered acceptable within the context of WCTHA and for the purposes of this work, aiming at providing a first glance of the potential hazard of landslide-tsunamis in the area.

3.1 Landslide simulations

The code UBO-BLOCK has been applied to each of the scenarios described in the previous section. The software requires as input the initial landslide configuration (the undisturbed sliding surface and the upper surface of the mass), the predefined trajectory of the CoM and the lateral boundaries of the surface swept by the sliding motion. In this way it is possible to obtain the time history of the landslide shape changes and of its dynamics, representing the input for the computation of the tsunamigenic impulse.

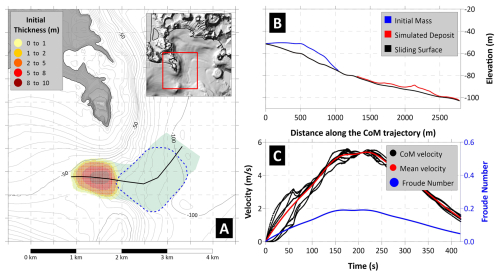

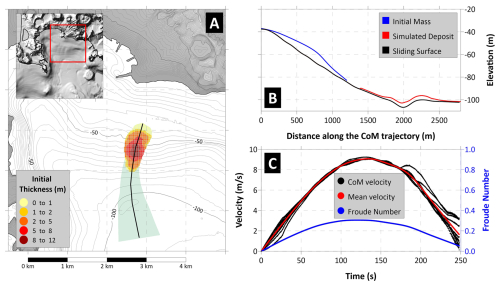

3.1.1 Scenario 1

The first scenario is submarine, with a volume around 3 million m3, and is placed south of Capo Miseno. Figure 4A shows the initial thickness distribution (yellow-red scale), and the predefined trajectory for the CoM, that has been determined based on the position of the final deposit found from the geomorphological survey (dashed-blue boundary). Figure 4B reports a section of the landslide, taken along the CoM trajectory: as previously noticed, the slopes are quite gentle, with an average value of 1.5° for this case. In the simulation, the sliding mass settles between 80 and 100 m sea depth (red line, Fig. 4B), reaching a maximum velocity of around 5 m s−1 after 200 s (Fig. 4C), and decelerating quickly due to low seafloor gradient. Figure 4C reports the Froude number (Fr) evolution in time as well: this dimensionless quantity is computed as the ratio between the horizontal component of the landslide velocity and the tsunami phase velocity in the shallow-water approximation (, with g gravitational acceleration and h water depth). When Fr approaches the unity, the velocities of the two quantities are similar, and the mass-wave system reaches resonance condition; for supercritical values (Fr>1) the mass moves faster than the wave: this occurs mainly in shallow water; in the subcritical regime (Fr<1), typical of submarine slides, the wave travels much faster than the slide, which is then unable to “feed” the main tsunami front. In other words, Fr provides an indication of the efficiency of the energy transfer from the sliding mass to the wave. As already mentioned, in this investigation the wave-mass feedback (i.e. the effect of the generated tsunami on the slide motion) is not accounted for. For Scenario 1, Fr attains maximum values around 0.2 corresponding to the velocity peak, accounting then for a poor efficiency in the tsunami generation process.

Figure 4Panel (A) Map of the initial sliding mass for Scenario 1, with initial thickness shown by the yellow-red scale. The black line marks the CoM predefined trajectory, defined to fit the observed deposit (dashed-blue boundary). The area swept by the sliding motion is highlighted in green. Panel (B) Landslide profile along the CoM trajectory: in black the undisturbed sliding surface; in blue the initial mass; in red the simulated deposit. Panel (C) Sliding velocity (red for average, black for each CoM) and Froude Number (in blue) time histories.

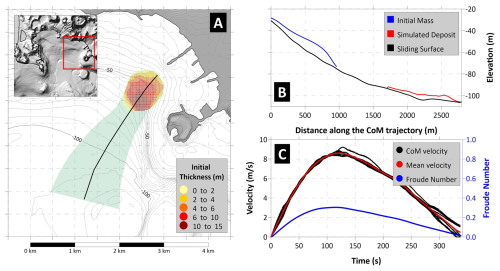

3.1.2 Scenario 2

The second scenario is still submarine and is placed in the central part of the Gulf of Pozzuoli, about 1 km offshore from the piers of the homonymous city (Fig. 5A). The hypothesized initial mass has been placed along the steeper slope connecting the shallow-water shelf to the deeper sea. The volume is similar to Scenario 1 (see Table 2), and the predefined sliding direction (black line in Fig. 5A) mainly extends in the north–south direction. The simulation shows the deposit reaching the sub-horizontal seafloor at about 100 m depth (Fig. 5B), with acceleration and deceleration phases almost symmetric, around the peak velocity value of 9 m s−1 (Fig. 5C). The maximum value of Fr is here higher than the previous case (more than 0.3), remaining however largely subcritical and then limiting the build-up of the wave front.

Figure 5Panel (A) Map of the initial sliding mass for Scenario 2, with initial thickness shown by the yellow-red scale. The black line marks the CoM predefined trajectory. The area swept by the sliding motion is highlighted in green. Panel (B) Landslide profile along the CoM trajectory: in black the undisturbed sliding surface; in blue the initial mass; in red the simulated deposit. Panel (C) Sliding velocity (red for average, black for each CoM) and Froude Number (in blue) time histories.

3.1.3 Scenario 3

The last submarine scenario is located on the eastern side of the basin, just north of the small peninsula of Nisida and few hundreds of meters offshore Bagnoli (Fig. 6A). As for the previous cases, the initial thickness is shown by the area in the yellow-red scale, showing that the mass is not distributed uniformly, but with the thicker part placed in deeper water. The sliding motion follows the main bathymetric gradient, south-westward (black line, Fig. 6A), stopping at about 100 m depth, where the slope is quite horizontal (Fig. 6B). The dynamics is characterized by a shorter acceleration phase, reaching the maximum velocity of almost 9 m s−1 after around 2 min (Fig. 6C), followed by a longer deceleration taking 4 min before stopping. Similarly to scenario 2, Fr attains maximum values of 0.3, meaning poor efficiency in tsunami generation.

Figure 6Panel (A) Map of the initial sliding mass for Scenario 3, with initial thickness shown by the yellow-red scale. The black line marks the CoM predefined trajectory. The area swept by the sliding motion is highlighted in green. Panel (B) Landslide profile along the CoM trajectory: in black the undisturbed sliding surface; in blue the initial mass; in red the simulated deposit. Panel (C) Sliding velocity (red for average, black for each CoM) and Froude Number (in blue) time histories.

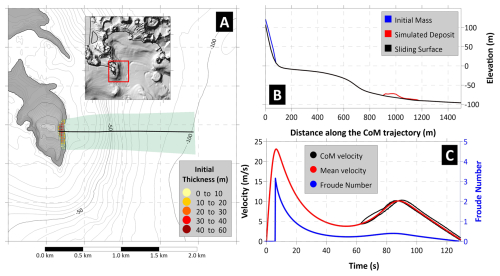

3.1.4 Scenario 4

This scenario is the only subaerial one and presents very different morphological features compared to the previously illustrated cases: much smaller volume and initial area (see Table 2), much larger initial thickness, and an aspect ratio (length/width) very different from the submarine cases, as visible from Fig. 7A. The initial mass has been hypothesized “filling” the subaerial, coastal scar still visible now along the eastern flank of Capo Miseno. Though purely theoretical, this type of collapse is not unusual in the whole area of the Gulf of Naples, as testified by the 30 June 2025 event at Punta Pennata, located close to this area; this scenario can be considered an endmember for this category of landslides.

The simulation shows that the deposit reaches a sub-horizontal area at 70–80 m depth (Fig. 7B), with dynamics again different from the previous cases: a sudden acceleration brings the sliding mass at about 23 m s−1 within 10 s (Fig. 7C), due to the very steep slope characterizing the first part of the trajectory (black line in Fig. 7B); then the submarine shelf in very shallow water provokes an abrupt deceleration, down to 5 m s−1, before a second acceleration due to the increasing slope between 20 and 60 m b.s.l., up to 10 m s−1. Finally, the slide stops about 2 min after the onset. The Froude number crossed the critical value after around 20 s, when the mass is decelerating and moving along the shallow water platform offshore Capo Miseno: this configuration turns out to be very efficient in generating the tsunami, since the waves are moving slower than in deep water and they are coupled with the mass motion on the seafloor.

Figure 7Panel (A) Map of the initial sliding mass for Scenario 4, with initial thickness shown by the yellow-red scale. The black line marks the CoM predefined trajectory. The area swept by the sliding motion is highlighted in green. Panel (B) Landslide profile along the CoM trajectory: in black the undisturbed sliding surface; in blue the initial mass; in red the simulated deposit. Panel (C) Sliding velocity (red for average, black for each CoM) and Froude Number (in blue) time histories.

3.2 Tsunami simulations

As illustrated previously, tsunamis can be significantly affected, during the propagation, by the hydrodynamic effect of dispersion, due to the different phase velocity characterizing its components. This phenomenon is particularly evident for short oscillations, which are more often induced by landslides. It is possible to estimate the distance at which such effects become predominant through Eq. (1), applying it to each of the studied scenarios. The dispersion can be quantified through the ratio , with λ tsunami wavelength and h sea depth that can be determined as follows:

-

λ, the initial wavelength of the tsunami, can be assessed in a first approximation as twice the longitudinal length of the slide, called b. This assumption, adopted in Heidarzadeh et al. (2023), though quite simplistic and rough, provides a first reasonable indication for this quantity.

-

Since the focus here goes to the minimum value for the ratio , delimiting the validity of SW approach, a value representing the maximum depth h for the tsunami propagation inside the Gulf of Pozzuoli is assumed: 105 m. The waves that are in the SW regime for this value, will satisfy this requirement also for shallower water.

Table 3 reports the estimations obtained for the landslide scenarios here adopted: the three submarine cases are in the SW regime, with the dispersion manifesting only for distances larger than the Gulf of Pozzuoli dimension. The subaerial case (Scenario 4) generates waves that are suddenly dominated by the dispersive effects: for this case the use of SW for the propagation on the whole Gulf of Pozzuoli seems not suitable.

Table 3Computation of the dispersion distance for the four scenarios here studied (b landslide length; λ: initial wavelength, assumed to coincide with 2b; h water depth (fixed at 105 m); D dispersion distance, computed by Eq. (1); d: distance for which dispersion effects become predominant.

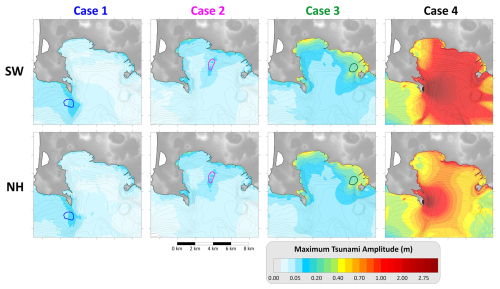

The simulations of the tsunamis generated by the sliding scenarios were performed using the JAGURS software, employing both the SW and the non-hydrostatic (NH) approaches, with the non-linear version of the equations in both cases. The computational grid resolution (20 m) is considered sufficient to investigate most of the tsunami features of interest in this work; grid nesting (meaning higher resolution grid in specific, target areas) is thus not implemented here. This strategy allows to investigate the suitability of the considerations previously made on the effects of dispersion on the tsunami propagation. Figure 8 illustrates the maximum water amplitude on each point of the computational domain for each scenario, comparing the two approaches: SW (upper row of plots) and NH (lower row). For the submarine scenarios (1, 2 and 3) the differences are negligible; for Case 4 (last column) significant differences are evident, with the NH approach showing much more localized effects compared to SW. This confirms the earlier hypothesis that dispersion effects cannot be neglected for sources of this type.

Figure 8Maximum water amplitude on each node of the computational grid for the four scenarios considered: each of them are simulated through the shallow-water (SW) and the Boussinesq (NH) approach. The coloured boundaries report the initial position of the respective landslide source.

From a hazard assessment perspective, the submarine scenarios here treated generate relatively small tsunamis in the Gulf of Pozzuoli. In Cases 1 and 2, the maximum wave amplitudes are on the order of some tens of centimetres. In Case 3, the maximum amplitude exceeds 50 cm along the coastal stretch between Bagnoli and Nisida, which, while not catastrophic, could still cause damages to small boats and generate currents in smaller sub-basins. In contrast, Case 4 produces more significant waves, especially at the local scale. Although the NH simulations show a rapid damping, localized amplifications can be observed in more distant coastal stretches, such as around Pozzuoli (northern coast) and the Nisida peninsula (on the east).

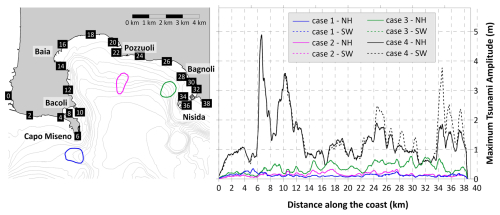

Figure 9 depicts the maximum tsunami amplitude along the coast vs. the cumulative coastal distance, measured from the eastern extreme of the computational domain and represented with the black labels, in the left plot. The SW–NH simulations are almost indistinguishable for the three submarine scenarios (right plot in Fig. 9), with the respective waves amplitude that are almost superimposed. Cases 1 and 2 show limited effects on the coast, while Case 3 generates maximum amplitudes of over 0.5 m between Pozzuoli and Nisida. As previously observed, on the contrary, for the subaerial case (Scenario 4) the dispersive effects play a key role, lowering considerably the maximum amplitude at the coast starting from the Pozzuoli coastal stretch (around 20 km of cumulative distance along the coast), with values almost halved at the opposite side of the Gulf. Conversely, the two approaches produce similar waves for coastal stretches closer to the source, since for these the tsunami travels in shallower water and the dispersive effects are then less intense. As already observed, this scenario produces the most impacting tsunami, with peak value close to 5 m in Capo Miseno and local amplifications at Pozzuoli and Nisida with amplitudes of almost 2 m.

Figure 9The map on the left reports the initial boundaries of the landslide scenarios. The cumulative distance along the coast is measured from the eastern extreme of the computational domain. The plot on the right depicts the maximum water amplitude along the coast for the four scenarios, with comparison between NH (continuous lines) and SW (dashed lines).

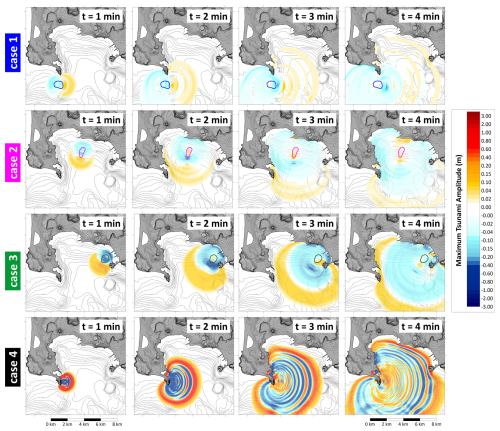

Figure 10 depicts the sketches of the first minutes of propagation for each scenario: all simulations show the typical feature characterizing landslide-tsunamis, the almost circular shape of the tsunami signal, mimicking a point-like source. This polar symmetry is lost when the wave interacts with shallow water and non-linear effects become predominant. A positive front (yellow-red scale, meaning sea level increase) propagates in the same direction of the sliding motion, while a negative one (cyan-blue scale) moves in the opposite side. For cases 2 and 3, the first manifestation of the tsunami at the coastal stretch close to the source – presumably affected by the larger waves – is a negative signal, meaning that the water withdraws and is followed later by a sea level increase: in terms of early warning this is undoubtedly an advantage, since it can act as a precursor of an upcoming flooding. For case 1 the situation is different, since the slide motion does not have a direction opposite to the dryland: a positive front enters the Gulf of Pozzuoli, while a negative one moves west of Capo Miseno, to the coastal stretch out of the basin. As to case 4, the sliding motion starts in the subaerial environment, resulting into an always positive tsunami front. Notice also the sequence of high frequency waves characterizing this scenario, especially evident in the 3 and 4 min sketches (last row of plots), reflecting the smaller spatial dimensions of the tsunami source.

Figure 10Propagation sketches at 1 min intervals of the four landslide-tsunami scenarios investigated (NH approach). The yellow-red scale marks the positive values (sea level increase), the cyan-blue scale is for negative ones (sea level sinking). The coloured contours represent the respective initial landslide boundary.

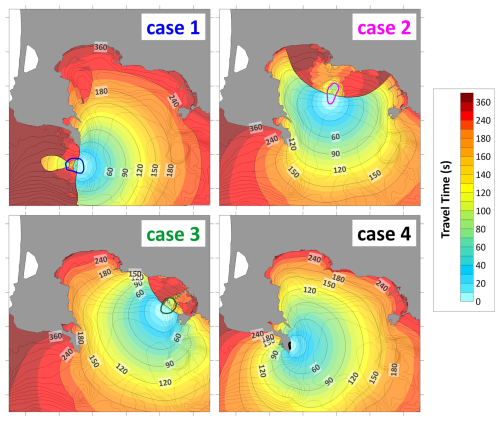

In all cases represented in Fig. 10, the tsunami affects most of the Gulf of Pozzuoli coasts within 4 min. Figure 11 reports the travel time for each point of the computational domain, providing precious insights from the warning point of view: independently from the initial position, the waves take approximately 3–6 min to affect all the coasts of the basin. Case 2 is the fastest, also due to its position at the centre of the Gulf. The north-western coastal stretch, on the contrary, is the one reached latest (5–6 min) in every scenario: the waves are slowed down by the shallow-water shelf that in this area is particularly large, compared to the other areas (as confirmed by the morphology, Fig. 4). It is worth to specify that the code JAGURS registers the first positive signal for each computational cell: this explains the anomalous pattern of the tsunami opposite to the slide direction, particularly evident in Case 1 (westward, upper left panel, Fig. 11) and Case 2 (northward, upper right panel).

The numerical simulations illustrated in the previous section provide some precious insights about the tsunami hazard pattern within the Gulf of Pozzuoli. Submarine collapses of the size adopted in this study generate waves that do not represent a threat for coastal population. However, they can damage harbour facilities and small boats, which are present in a great number within the Gulf of Pozzuoli. Conversely, the subaerial scenario produces high waves especially in the near field (almost 5 m high), which rapidly attenuate with distance thanks to dispersive effects. Some distant coastal stretches are affected by local amplifications, with maximum amplitudes reaching almost 2 m (Pozzuoli, Nisida), highlighting the need to investigate this type of events. In most cases, the tsunami reaches the shoreline in a few minutes with a positive signal, meaning that it manifests as a water level increase. Only in limited coastal stretches, and not for all scenarios, the first signal is negative, i.e., the sea withdraws for some minutes, providing a crucial precursor of an incoming wave in terms of early warning. In a few words, these events can occur totally unannounced, reflecting the definition of “surprise tsunamis” given in Ward (2001). In the following, some specific issues arising from the approach adopted and the simulation results are discussed.

4.1 Landslide-tsunami modelling

As shown, the scenarios considered involve heterogeneous contexts, occurring both in subaerial and submarine environment. The use of the same modelling approach for both type of events deserves some discussion. The interaction of a subaerial slide impacting water encompasses all the three phases (solid–liquid–air), resulting in a highly three-dimensional, nonlinear process that is particularly difficult to simulate, especially near the source area. To address this complexity, the phenomenon is typically divided into two main phases: (i) the “splash-zone”, where such unsteady, complex interactions dominate. The signals generated in this area, though intense and characterized by large amplitude, have high frequency and dissipate quickly (Abadie et al., 2008). Consequently, their effects are confined to a limited area, generally comparable in size to the slide run-out (Walder et al., 2006); (ii) the propagation phase, beyond the splash-zone, where a coherent, longer-period signal travels outward. Indeed, the tsunamigenic physical mechanism – whole water column uplift due to the passage of the mass on the seabed – is the same. These oscillations exhibit peculiar characteristics but are broadly analogous to submarine-generated tsunamis, apart from dispersive effects that can be captured by proper modelling. A comprehensive review about this topic is provided by Yavari-Ramshe and Ataje-Ashtiani (2016). In this study, the adopted modelling strategy deliberately neglects the splash-zone effects, assuming they are confined to a very narrow coastal stretch at Capo Miseno. Consequently, the tsunami hazard assessment for the broader Gulf of Pozzuoli could be considered reliable. This assumption is further supported by previous applications of the same numerical routine to other subaerial landslide-generated tsunamis, such as the 1783 Scilla landslide-tsunami (see Zaniboni et al., 2016; Zaniboni et al., 2019).

4.2 Landslide scenarios

The scenario approach here adopted is a consequence of the lack of knowledge about the underwater landslide bodies in the Gulf of Pozzuoli, and it is based on a worst-case methodology (WCTHA, Tonini et al., 2011; Zaniboni and Armigliato, 2026). Geophysical and bathymetric surveys have evidenced the presence of some ancient collapses, buried by the sediments, in the deeper part of the basin at the toe of the slopes, but a general pattern of mass transport processes in the Gulf of Pozzuoli, with recurrence time and volume estimation, does not exist. The sources adopted have been reconstructed based on the pieces of evidence found in the scientific literature and on geomorphological considerations (margin slopes, existing scars, basin depth), assuming that they are representative of the maximum credible occurrences expected in the area with the present morphology and knowledge of the area. As a result, three submarine masses have been reconstructed, with similar volumes (few million m3), thickness (a maximum of about ten meters) and detachment depth (in shallow water, between 30 and 50 m). The fourth case is a coastal subaerial collapse and is characterized by a very different morphology: it can be considered as the endmember of this type of landslide, since no direct evidence exists of bigger collapses interacting with the sea. Specific characteristics of each sliding scenario could not be retrieved from the available geological and geophysical evidence: then, reasonable and standard assumptions have been made for their rheology, hypothesizing for all of them a moderate translational behaviour. These scenarios cover the whole extent of the Gulf, providing then a general idea of the impact expected from the ensuing tsunamis. However, larger collapses cannot be ruled out, especially in case of intensification of the Campi Flegrei volcanic activity providing possible triggers and, in the long term, slope oversteepening.

4.3 Dispersion effects

For tsunamis of non-seismic origin, the effect of dispersion should be always taken into consideration, since it can change consistently the propagation pattern with respect to the classic SW approach. The discrepancy grows with the distance from the source, depending on the wavelength of the initial signal and on the depth of the basin where the perturbation propagates. Equation (1) provided rough estimates of this distance for the scenarios considered (reported in Table 3), suggesting that for the submarine cases the dispersion is negligible within the Gulf of Pozzuoli domain. Numerical simulations confirmed this hypothesis: the application of the code with (NH) and without (SW) dispersion produced almost identical tsunamis, proving that the simpler and faster approach is sufficient to assess properly the tsunami hazard for these cases. For the subaerial case, on the contrary, the difference is marked, as evidenced in Fig. 9 by the maximum amplitudes along the coast. The modelling effort, then, should consider the morphological features of the source generating the tsunami, keeping in mind that subaerial masses collapsing into the sea usually generate shorter perturbations. In these cases, dispersive effects can become relevant even for brief distances, and the application of the SW approach could produce an overestimation of the tsunami impact on the coasts.

4.4 Coastal and non-linear phenomena

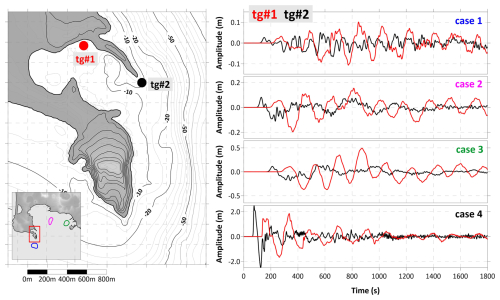

From the propagation plots (Fig. 10) it is possible to infer some peculiar features of the tsunami close to the coast, where the interaction with shallow water and minor basins can induce non-linear effects. For example, for case 2 a positive signal propagating in the Bacoli Bay – a minor inlet just north of Capo Miseno on the western part of the Gulf (see also Fig. 12 for location) – can be noticed, evident especially in the t=3 and 4 min sketches. This is visible, while less marked, also for the other scenarios, and suggests the possibility of the excitation of the normal modes of this sub-basin by the tsunami: this phenomenon, known as resonance, can occur for every basin affected by an external perturbation, and is for example the mechanism at the basis of the generation of the meteotsunamis (Vilibic et al., 2016). The morphology of the basin determines the periods of the resonant modes typical of the basin. Rabinovich (2009) obtained a set of simple expressions allowing to estimate them for basic geometries. For example, for an open rectangular basin of length L and uniform depth h, the period T of the fundamental mode is:

where g is the gravitational acceleration. Focusing on the Bacoli Bay case, Fig. 12 reports the marigrams obtained from two virtual tide gauges placed inside the inlet (tg#1, in red) and at its mouth (tg#2, in black), depicting the two respective time histories in the four scenarios considered. The comparison of the signals shows clearly, for Cases 1, 2 and 3, that inside the bay the perturbations behave as standing waves, characterized by regular oscillations lasting for at least 30 min (final simulation time) with an approximate period of 200 s and evident amplifications if compared to the oscillations out of the basin (in black). The tsunami generated by Case 3, in particular, is amplified five times with respect to the incoming signal. Assuming for the Bacoli Bay a simplified rectangular geometry (L≈1000 m, h≈5 m) and applying Eq. (2), one can estimate the fundamental mode as T≈200 s, in full agreement with the features deduced from the virtual tide gauges. Moreover, the subaerial scenario (Case 4) is less subject to the amplification when entering the inlet compared to the other cases, due to the shorter period characterizing its oscillations.

The Gulf of Pozzuoli covers a significant portion of the Campi Flegrei caldera, a region of significant geological and volcanic activity. Intense seismic and volcanic processes have the potential to destabilize large sliding bodies both in the subaerial and in the submarine environment. When these masses interact with the water, they can generate tsunamis that may impact the entire basin's coastline, posing potential risks to local communities, coastal infrastructures, and marine activities.

Despite the region being the object of extensive geological and geophysical investigations, a comprehensive understanding of mass transport processes remains limited. A worst-case, scenario-based approach is then adopted, analysing four representative cases, based on the limited geological evidence and on morphological considerations: three submarine bodies, with similar volume (few million m3, occurring in shallow water) and one subaerial slide (smaller mass, occurring on the coastline). These scenarios are not intended to reproduce actual occurrences, while they aim at quantifying the tsunami hazard associated to events of this entity, providing precious insights into the potential tsunami generation mechanisms and their subsequent impact on coastal areas, as an important basis for possible risk mitigation strategies.

The sliding dynamics and the resulting tsunamis are simulated using numerical techniques that account for key hydrodynamic phenomena such as dispersion, nonlinear coastal effects, and resonance.

The simulations results indicate that submarine landslides generally produce waves of limited amplitude on the coast, with a maximum height of 0.5 m, as observed for Case 3. While these tsunamis do not represent a major threat to coastal communities, they could still cause localized damages, for example to small boats moored in the harbours across the Gulf of Pozzuoli. Furthermore, resonance effects in smaller basins, such as harbours, can amplify an incoming wave, preventing its dissipation and resulting in standing wave affecting the coast for long time: simulation outcomes show that in the Bacoli Bay – placed in the western sector of the gulf – the incoming signal is amplified up to five times, with a sequence of regular oscillations with a period of 200 s, affecting the basin for at least 30 min, which reflects the normal modes typical of the inlet. This can repeat in every coastal basin, each one characterized by its own geometry and fundamental mode and is worthy of specific and detailed investigation, implementing also nested grids at higher resolution. In contrast, the subaerial slide scenario results in significantly larger waves, exceeding 4 m close to the source. The tsunami amplitude dampens rapidly with distance, due to dispersion, but in some coastal stretches, Pozzuoli on the north and Nisida on the east, it reaches almost 2 m.

The investigation here presented highlights the complex interplay between geological processes, hydrodynamic phenomena, and coastal hazard in the Gulf of Pozzuoli. The results emphasize the need for detailed study and monitoring of potential unstable masses both in the submarine and in the subaerial realm, determining their main features (geotechnical parameters, possible rheology) which can influence deeply the tsunamigenesis. Coastal subaerial events, in particular, can give rise to large tsunamis threatening the whole Gulf of Pozzuoli, enhancing the need for risk management strategies to mitigate the potential impact of tsunamis in this active volcanic region.

The numerical codes UBO-BLOCK and UBO-TSUIMP for landslide dynamics and tsunamigenic impulse computation respectively are available upon request to the authors; the code JAGURS can be freely downloaded from https://github.com/jagurs-admin/jagurs (last access: 20 January 2026) and https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3737815 (jagurs-admin, 2025).

The computational grids have been obtained from the elaboration of raw datasets available online, which have been interpolated and readjusted. They are available under request to the authors.

FZ and AA conceptualized the investigation; FZ, CA and MZ prepared the computational grids and the landslide scenario datasets; FZ and LS performed the simulations; FZ prepared the manuscript, with the contribution from all co-authors; FZ and AA supervised the whole manuscript realization.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. The authors bear the ultimate responsibility for providing appropriate place names. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

The authors are grateful to Jacopo Selva, University of Naples, Federico II, for the productive discussion about the potential tsunami sources in the Gulf of Pozzuoli related to the Campi Flegrei activity, and to the editor and the two anonymous reviewers for their constructive and insightful comments, improving considerably the manuscript.

This paper was edited by Rachid Omira and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Abadie, S., Morichon, D., Grilli, S., and Glockner, S.: VOF/Navier–Stokes numerical modeling of surface waves generated by subaerial landslides, La Houille Blanche, 1, 21–26, https://doi.org/10.1051/lhb:2008001, 2008.

Aiello, G., Marsella, E., and Fiore, V. D.: New seismo-stratigraphic and marine magnetic data of the Gulf of Pozzuoli (Naples Bay, Tyrrhenian Sea, Italy): inferences for the tectonic and magmatic events of the Phlegrean Fields volcanic complex (Campania), Mar. Geophys. Res., 33, 97–125, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11001-012-9150-8, 2012.

Baba, T., Ando, K., Matsuoka, D., Hyodo, M., Hori, T., Takahashi, N., Obayashi, R., Imato, Y., Kitamura, D., Uehara, H., Kato, T., and Saka, R.: Large-scale, highspeed tsunami prediction for the Great Nankai Trough Earthquake on the K computer, In. J. High Per. Comp. App., 30, https://doi.org/10.1177/1094342015584090, 2015.

Behrens, J., Løvholt, F., Jalayer, F., Lorito, S., Salgado-Gálvez, M. A., Sørensen, M., Abadie, S., Aguirre-Ayerbe, I., Aniel-Quiroga, I., Babeyko, A., Baiguera, M., Basili, R., Belliazzi, S., Grezio, A., Johnson, K., Murphy, S., Paris, R., Rafliana, I., De Risi, R., Rossetto, T., Selva, J., Taroni, M., Del Zoppo, M., Armigliato, A., Bureš, V., Cech, P., Cecioni, C., Christodoulides, P., Davies, G., Dias, F., Bayraktar, H. B., González, M., Gritsevich, M., Guillas, S., Harbitz, C. B., Kânoglu, U., Macías, J., Papadopoulos, G. A., Polet, J., Romano, F., Salamon, A., Scala, A., Stepinac, M., Tappin, D. R., Thio, H. K., Tonini, R., Triantafyllou, I., Ulrich, T., Varini, E., Volpe, M., and Vyhmeister, E.: Probabilistic Tsunami Hazard and Risk Analysis: A Review of Research Gaps, Front. Earth Sci., 9, 628772, https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2021.628772, 2021.

Bevilacqua, A., Isaia, R., Neri, A., Vitale, S., Aspinall, W. P., Bisson, M., Flandoli, F., Baxter, P. J., Bertagnini, A., Esposti Ongaro, T., Iannuzzi, E., Pistolesi, M., and Rosi, M.: Quantifying volcanic hazard at Campi Flegrei caldera (Italy) with uncertainty assessment: 1. Vent opening maps, J. Geophys. Res.-Sol. Ea., 120, 2309–2329, https://doi.org/10.1002/2014JB011775, 2015.

Calcaterra, D. and Di Martire, D.: Landslide Hazard and Risk in the Campi Flegrei Caldera, Italy, in: Campi Flegrei. Active Volcanoes of the World, edited by: Orsi, G., D'Antonio, M., and Civetta, L., Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-37060-1_13, 2022.

Danesi, S., Pino, N. A., Carlino, S., and Kilburn, C. R.: Evolution in unrest processes at Campi Flegrei caldera as inferred from local seismicity, Earth Planet. Sc. Lett., 626, 118530, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2023.118530, 2024.

De Natale, G., Troise, C., Pingue, F., Mastrolorenzo, G., Pappalardo, L., Battaglia, M., and Boschi, E.: The Campi Flegrei caldera: unrest mechanisms and hazards, in: Mechanisms of Activity and Unrest at Large Calderas, edited by: Troise, C., De Natale, G., and Kilburn, C. R. J., Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 269, https://doi.org/10.1144/GSL.SP.2006.269.01.03, 2006.

De Ritis, R., Cocchi, L., Passaro, S., and Chiappini, M.: Giant landslide, hidden caldera structure, magnetic anomalies and tectonics in southern Tyrrhenian Sea (Italy), Geomorphology, 466, 109445, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2024.109445, 2024.

De Vivo, B., Rolandi, G., Gans, P. B., Calvert, A., Bohrson, W. A., Spera, F. J., and Belkin, H. E.: New constraints on the pyroclastic eruptive history of the Campanian volcanic Plain (Italy), Miner. Petrol., 73, 47–65, https://doi.org/10.1007/s007100170010, 2001.

De Vivo, B., Belkin, H. E., and Rolandi, G.: Introduction to Vesuvius, Campi Flegrei, and Campanian Volcanism, in: Vesuvius, Campi Flegrei, and Campanian Volcanism, edited by: De Vivo, B., Belkin, H. E., and Rolandi, G., Elsevier, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-816454-9.00001-8, 2020.

Del Gaudio, C., Aquini, I., Ricciardi, G. P., Ricco, C., and Scandone, R.: Unrest episodes at Campi Flegrei: A reconstruction of vertical ground movements during 1905–2009, J. Volcanol. Geoth. Res., 195, 10, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2010.05.014, 2010.

Di Vito, M., Acocella, V., Aiello, G., Barra, D., Battaglia, M., Carandente, A., Del Gaudio, C., de Vita, S., Ricciardi, G. P., Ricco, C., Scandone, R., and Terrasi, F.: Magma transfer at Campi Flegrei caldera (Italy) before the 1538 AD eruption, Sci. Rep.-UK, 6, 32245, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep32245, 2016.

DPC (Dipartimento della Protezione Civile – Civil Protection Department, Italy): MaGIC – Marine Geohazards along the Italian Coasts, https://github.com/pcm-dpc/MaGIC, last access: 18 May 2023.

Ehara, A., Salmanidou, D. M., Heidarzadeh, M., and Guillas, S.: Multi-level emulation of tsunami simulations over Cilacap, South Java, Indonesia, Computational Geosciences, 27, 127–142, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10596-022-10183-1, 2023.

Esposito, G. and Matano, F.: A geodatabase of historical landslide events occurring in the highly urbanized volcanic area of Campi Flegrei, Italy, Earth Syst. Sci. Data, 15, 1133–1149, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-15-1133-2023, 2023.

Gallotti, G., Zaniboni, F., Pagnoni, G., Romagnoli, C., Gamberi, F., Marani, M., and Tinti, S.: Tsunamis from prospected mass failure on the Marsili submarine volcano flanks and hints for tsunami hazard evaluation, B. Volcanol., 83, 2, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00445-020-01425-0, 2021.

Gallotti, G., Zaniboni, F., Arcangeli, D., Angeli, C., Armigliato, A., Cocchi, L., Muccini, F., Zanetti, M., Tinti, S., and Ventura, G.: The tsunamigenic potential of landslide-generated tsunamis on the Vavilov seamount, J. Volcanol. Geoth. Res., 434, 107745, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2023.107745, 2023.

Gasperini, L., Zaniboni, F., Armigliato, A., Tinti, S., Pagnoni, G., Özeren, M. S., Ligi, M., Natali, F., and Polonia, A.: Tsunami potential source in the eastern Sea of Marmara (NW Turkey), along the North Anatolian Fault system, Landslides, 19, 2295–2310, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10346-022-01929-0, 2022.

Glimsdal, S., Pedersen, G. K., Harbitz, C. B., and Løvholt, F.: Dispersion of tsunamis: does it really matter?, Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci., 13, 1507–1526, https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-13-1507-2013, 2013.

Grezio, A., Cinti, F. R., Costa, A., Faenza, L., Perfetti, P., Pierdominici, S., Pondrelli, S., Sandri, L., Tierz, P., Tonini, R., and Selva, J.: Multisource Bayesian probabilistic tsunami hazard analysis for the Gulf of Naples (Italy), J. Geophys. Res.-Oceans, 125, 2, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019JC015373, 2020.

Harbitz, C. B., Løvholt, F., Pedersen, G., and Masson, D. G.: Mechanisms of tsunami generation by submarine landslides: a short review, Norwegian J. Geol., 86, 255–264, ISSN 029-196X, 2006.

Heidarzadeh, M., Gusman, A. R., and Mulia, I. E.: The landslide source of the eastern Mediterranean tsunami on 6 February 2023 following the Mw 7.8 Kahramanmaraş (Türkiye) inland earthquake, Geosci. Lett., 10, 50, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40562-023-00304-8, 2023.

Isaia, R., Di Giuseppe, M. G., Natale, J., Tramparulo, F. D. A., Troiano, A., and Vitale, S.: Volcano-tectonic setting of the Pisciarelli fumarole field, Campi Flegrei caldera, southern Italy: insights into fluid circulation patterns and hazard scenarios, Tectonics, 40, 5, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020TC006227, 2021.

jagurs-admin: jagurs-admin/jagurs: Release of JAGURS-D_V0610 (JAGURS-D_V0610), Zenodo [code], https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15321436, 2025.

Løvholt, F., Pedersen, G., Harbitz, C. B., Glimsdal, S., and Kim, J.: On the characteristics of landslide tsunamis, Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A, 373, 20140376, https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2014.0376, 2015.

Mayer, K., Scheu, B., Montanaro, C., Yilmaz, T. I., Isaia, R., Aßbichler, D., and Dingwell, D. B.: Hydrothermal alteration of surficial rocks at Solfatara (Campi Flegrei): Petrophysical properties and implications for phreatic eruption processes, J. Volcanol. Geoth. Res., 320, 128–143, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2016.04.020, 2016.

Neri, A., Bevilacqua, A., Esposti Ongaro, T., Isaia, R., Aspinall, W. P., Bisson, M., Flandoli, F., Baxter, P. J., Bertagnini, A., Iannuzzi, E., Orsucci, S., Pistolesi, M., Rosi, M., and Vitale, S.: Quantifying volcanic hazard at Campi Flegrei caldera (Italy) with uncertainty assessment: 2. Pyroclastic density current invasion maps, J. Geophys. Res.-Sol. Ea., 120, 4, 2330–2349, https://doi.org/10.1002/2014JB011776, 2015.

Paris, R., Ulvrová, M., Selva, J., Brizuela, B., Costa, A., Grezio, A., Lorito, S., and Tonini, R.: Probabilistic hazard analysis for tsunamis generated by subaqueous volcanic explosions in the Campi Flegrei caldera, Italy. J. Volcanol. Geoth. Res., 379, 106–116, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2019.05.010, 2019.

Perrotta, A., Scarpati, C., Luongo, G., and Morra, V.: The Campi Flegrei caldera boundary in the city of Naples, in: Developments in Volcanology, edited by: De Vivo, B., vol. 9, Elsevier, 85–96, https://doi.org/10.1016/S1871-644X(06)80019-7, 2006.

Rabinovich, B. A.: Seiches and Harbor Oscillations, Handbook of Coastal and Ocean Engineering, 93–236, https://doi.org/10.1142/9789812819307_0009, 2009.

Ren, Z., Hou, J., Wang, P., and Wang, Y.: Tsunami resonance and standing waves in Hangzhou Bay, Physics of Fluids, 33, 8, https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0059383, 2021.

Rosi, M., Sbrana, A., and Principe, C.: The Phlegraean Fields: structural evolution, volcanic history and eruptive mechanisms, J. Volcanol. Geoth. Res., 17, 273–288, https://doi.org/10.1016/0377-0273(83)90072-0, 1983.

Sabino, L.: Analisi della pericolosità da tsunami generati da frana nell'area del Golfo di Pozzuoli e dei Campi Flegrei, Second Level Degree in Physics of the Earth System, discussed on 14 march 2024, thesis dissertation, 2024 (in Italian).

Saito, T.: Tsunami Generation and Propagation, vol. 265, Springer Geophysics, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-4-431-56850-6, 2019.

Selva, J., Amato, A., Armigliato, A., Basili, R., Bernardi, F., Brizuela, B., Cerminara, M., de' Micheli Vitturi, M., Di Bucci, D., Di Manna, P., Esposti Ongaro, T., Lacanna, G., Lorito, S., Løvholt, F., Mangione, D., Panunzi, E., Piatanesi, A., Ricciardi, A., Ripepe, M., Romano, F., Santini, M., Scalzo, A., Tonini, R., Volpe, M., and Zaniboni, F.: Tsunami risk management for crustal earthquakes and non-seismic sources in Italy, Riv. Nuovo Cim., 44, 69–144, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40766-021-00016-9, 2021.

Somma, R., Iuliano, S., Matano, F., Molisso, F., Passaro, S., Sacchi, M., Troise, C., and De Natale, G.: High-resolution morpho-bathymetry of Pozzuoli Bay, southern Italy, Journal of Maps, 12, 222–230, https://doi.org/10.1080/17445647.2014.1001800, 2016.

Tarquini, S., Isola, I., Favalli, M., Battistini, A., and Dotta, G.: TINITALY, a digital elevation model of Italy with a 10 m cell size (Version 1.1), Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia (INGV), https://doi.org/10.13127/tinitaly/1.1, 2023.

Tinti, S., Bortolucci, E., and Vannini, C.: A block-based theoretical model suited to gravitational sliding, Nat. Hazards, 16, 1–28, https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007934804464, 1997.

Tinti, S., Pagnoni, G., and Zaniboni, F.: The landslides and tsunamis of 30th December 2002 in Stromboli analysed through numerical simulations, B. Volcanol., 68, 462–479, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00445-005-0022-9, 2006.

Tonini, R., Armigliato, A., Pagnoni, G., Zaniboni, F., and Tinti, S.: Tsunami hazard for the city of Catania, eastern Sicily, Italy, assessed by means of Worst-case Credible Tsunami Scenario Analysis (WCTSA), Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci., 11, 1217–1232, https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-11-1217-2011, 2011.

Triantafyllou, I., Zaniboni, F., Armigliato, A., Tinti, S., and Papadopoulos, G. A.: The Large Earthquake (∼M7) and Its Associated Tsunami of 8 November 1905 in Mt. Athos, Northern Greece, Pure Appl. Geophys., 177, 1267–1293, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00024-019-02363-5, 2020.

Vilibić, I., Šepić, J., Rabinovich, A. B., and Monserrat, S.: Modern approaches in meteotsunami research and early warning, Frontiers in Marine Science, 3, 57, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2016.00057, 2016.

Walder, J. S., Watts, P., Waythomas, C. F.: Case study: mapping tsunami hazards associated with debris flow into a reservoir, J. Hydraul. Eng., 132, 1–11, https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9429(2006)132:1(1), 2006.

Ward, S. N.: Landslide tsunami, J. Geophys. Res., 106, 11201–11215, https://doi.org/10.1029/2000JB900450, 2001.

Yavari-Ramshe, S. and Ataie-Ashtiani, B.: Numerical modeling of subaerial and submarine landslide-generated tsunami waves – recent advances and future challenges, Landslides, 13, 1325–1368, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10346-016-0734-2, 2016.

Zaniboni, F. and Armigliato, A.: Worst-case tsunami approach applied to Catania (eastern Sicily), in: Probabilistic Tsunami Hazard and Risk Analysis, edited by: Sørensen, M., Behrens, J., Jalayer, F., Løvholt, F., Lorito, S., Rafliana, I., Salgado, M., and Selva, J., Springer Nature, Switzerland, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-98115-9, 2026.

Zaniboni, F., Armigliato, A., and Tinti, S.: A numerical investigation of the 1783 landslide-induced catastrophic tsunami in Scilla, Italy, Nat. Hazards, 84, S455–S470, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-016-2461-3, 2016.

Zaniboni, F., Pagnoni, G., Gallotti, G., Paparo, M. A., Armigliato, A., and Tinti, S.: Assessment of the 1783 Scilla landslide–tsunami's effects on the Calabrian and Sicilian coasts through numerical modeling, Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci., 19, 1585–1600, https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-19-1585-2019, 2019.

Zaniboni, F., Pagnoni, G., Paparo, M. A., Gauchery, T., Rovere, M., Argnani, A., Armigliato, A., and Tinti, S.: Tsunamis From Submarine Collapses Along the Eastern Slope of the Gela Basin Strait of Sicily, Front. Earth Sci. 8, 602171, https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2020.602171, 2021.

Zaniboni, F., Pagnoni, G., Gallotti, G., Tinti, S., and Armigliato, A.: Landslide-tsunamis along the flanks of Mount Epomeo, Ischia: propagation patterns and coastal hazard for the Campania Coasts, Italy, in: Volcanic Island: from Hazard Assessment to Risk Mitigation, edited by: Marotta, E., D'Auria, L., Zaniboni, F., and Nave, R., Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 519, https://doi.org/10.1144/SP519-2020-128, 2024.

Zollo, A., Maercklin, N., Vassallo, M., Dello Iacono, D., Virieux, J., and Gasparini, P.: Seismic reflections reveal a massive melt layer feeding Campi Flegrei caldera, Geophys. Res. Lett., 35, 12, https://doi.org/10.1029/2008GL034242, 2008.