the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Review article: Deep learning for potential landslide identification: data, models, applications, challenges, and opportunities

Pan Jiang

Zhengjing Ma

Gang Mei

As global climate change and human activities escalate, the frequency and severity of landslide hazards have been increasing. Early identification, as an important prerequisite for monitoring, evaluation, and prevention, has become increasingly critical. Deep learning, as a powerful tool for data interpretation, has demonstrated remarkable potential in advancing landslide identification, particularly through the automated analysis of remote sensing, geological, and topographic data. This review systematically examines and synthesizes over 400 studies, with a primary focus on literature from the last six years (2020–2025), alongside key foundational works. It provides a comprehensive overview of recent advancements in the utilization of deep learning for potential landslide identification. First, the sources and characteristics of landslide-related data are summarized, including satellite observation data, airborne remote sensing data, and ground-based observation data. Next, commonly used deep learning models are classified based on their roles in potential landslide identification, such as image analysis and time series analysis. Then, the role of deep learning in identifying rainfall-induced landslides, earthquake-induced landslides, human activity-induced landslides, and multi-factor-induced landslides is summarized. Although deep learning has achieved considerable success in landslide identification, it still faces several challenges, including data imbalance, limited model generalization, and the inherent complexity of landslide mechanisms. Finally, future research directions in this field are discussed. It is suggested that integrating knowledge-driven and data-driven approaches for potential landslide identification will further enhance the applicability of deep learning, offering broad prospects for future research and practice.

- Article

(8400 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

Landslides are complex geological hazards triggered by both natural processes and human activities, involving intricate interactions among geological, hydrological, topographic, and meteorological factors (Fidan et al., 2024). Globally, landslides cause significant loss of life and property each year, particularly in mountainous areas with intense rainfall, seismic activity, and fragile geological conditions (Askarinejad et al., 2018; Ehsan et al., 2025; Marín-Rodríguez et al., 2024). According to United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (2023), more than 1000 landslide-related disasters occur annually, resulting in thousands of fatalities and substantial economic damage. With the intensification of climate change, extreme weather events are becoming more frequent, further increasing global landslide risks (Wang et al., 2023c).

Faced with these escalating threats, the focus of landslide risk management should shift from post-disaster response toward proactive identification and prevention. Potential landslides refer to slopes that exhibit early signs of instability and may evolve into landslides under external triggers such as rainfall or earthquakes. They represent the precursor stage of landslide development (Lin et al., 2024; Yang et al., 2020). Timely identification and monitoring of such slopes are crucial for disaster prevention and risk mitigation (Strzabala et al., 2024).

However, the inherent uncertainty and dynamic nature of potential landslides make their identification challenging. On the one hand, it is not possible to determine that a landslide will definitely occur just because there are signs of deformation on the slope (Peres and Cancelliere, 2014; Zhang et al., 2019). Multiple factors need to be comprehensively considered to assess the possibility of its instability. On the other hand, the uncertainty of external factors increases the difficulty of judgment. Sudden events such as heavy rainfall and earthquakes may instantly change the stress state of the slope and trigger signs of deformation (Yang et al., 2024c). Given the dynamic characteristics of potential landslides, it is also essential to conduct long-term monitoring of the landslides with potential hazards after identification (Lakhote et al., 2025).

Conventional approaches to potential landslide identification, including field surveys, geological analysis, and interferometric radar techniques, have contributed substantially to hazard assessment but remain costly, time-consuming, and limited in spatial coverage (Akosah et al., 2024; Zhao and Lu, 2018). Machine learning has partially improved efficiency but still depends heavily on manual feature engineering, requiring expert knowledge to design relevant predictors (Sheng et al., 2023). These limitations restrict the scalability and adaptability of conventional approaches in complex geospatial environments.

In contrast, deep learning provides an effective data-driven alternative for landslide research. As a subfield of machine learning, deep learning performs hierarchical feature extraction through multiple nonlinear transformations (Janiesch et al., 2021; Nava et al., 2023). By leveraging large-scale, multi-source data, deep learning models can automatically extract representative features, capture nonlinear dependencies, and conduct pattern recognition in high-dimensional datasets (Aslam et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2023a; Zhou et al., 2023). These capabilities make deep learning particularly suitable for identifying and characterizing potential landslides across diverse spatial and temporal scales (Nava et al., 2021; Yang et al., 2024d).

Within this research context, potential landslide identification can be broadly categorized into two main types. The first focuses on post-event regional assessments, which are conducted after major rainfall or earthquakes but prior to large-scale slope failures, using remote sensing data to detect deformation, topographic changes, or vegetation anomalies. The second involves retrospective analyses of historical landslides to establish relationships between triggering factors and failure characteristics, thereby identifying other slopes that exhibit similar instability patterns. Despite their differing temporal focuses, both types share common methodological foundations and depend on the integration of multi-source environmental data for reliable assessment.

Building on these foundations, this review aims to provide a comprehensive synthesis of deep learning applications in the field of potential landslide identification. Specifically,

-

we categorize commonly used heterogeneous data into three major types to support research on potential landslide identification. These data sources form the foundation for applying deep learning in this field.

-

we introduce the roles and mechanisms of widely used deep learning models in potential landslide identification, and conduct a comparative analysis of their respective advantages and limitations.

-

we examine the performance of these models across different application scenarios through representative case studies, highlighting their adaptability and effectiveness in potential landslide detection.

-

we summarize the key challenges currently faced in applying deep learning to potential landslide identification and outline emerging opportunities and promising future directions for further advancement.

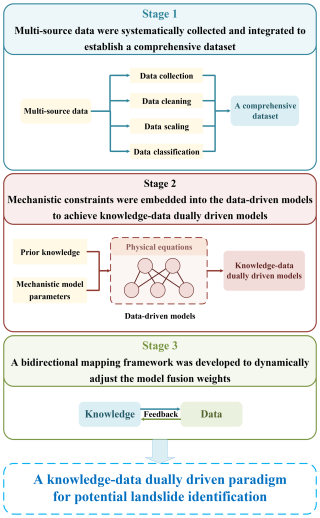

Through our analysis, we identified several key trends in the application of deep learning to potential landslide identification. First, researchers are increasingly adopting multi-source data fusion approaches, integrating information from diverse sources to construct a more comprehensive representation of the geological environment (Guo et al., 2025; Liu et al., 2020b; Wang et al., 2024d). Second, deep learning models have been successfully applied across multiple scales, ranging from large-scale landslide susceptibility mapping with Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) to real-time slope deformation monitoring with Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) (Azarafza et al., 2021; Soni et al., 2025; Xie et al., 2024; Zhao et al., 2024f). Despite these advances, the field continues to face critical challenges that will shape its future trajectory. Addressing these challenges requires a paradigm shift, future research is expected to place greater emphasis on integrating physical knowledge with data-driven approaches, thereby advancing the field from conventional, reactive post-disaster responses toward intelligent, proactive pre-disaster risk management.

Accurate identification of potential landslides is the primary step in effectively preventing and mitigating the impacts of landslide hazards. Data sources are the cornerstone of achieving this objective. Different types of data provide indispensable information for potential landslide identification from various perspectives, and drive ongoing advancements in related research and practices.

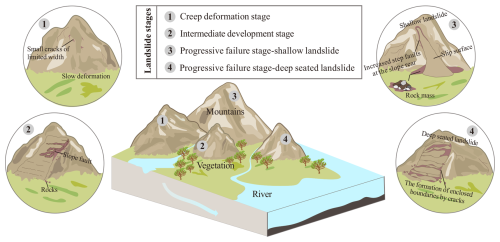

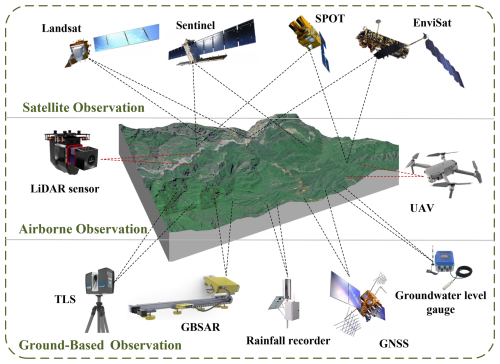

In potential landslide identification, the richness and reliability of data sources directly determine the accuracy and effectiveness of research. Data sources not only provide fundamental information to outline the landslide environments, but also enable dynamic monitoring and precise analysis. This section will comprehensively review the critical roles played by three main types of data sources: satellite observation data, airborne remote sensing data, and ground-based observation data (see Fig. 1).

2.1 Satellite Observation Data

Since the launch of Landsat-1, the first Earth observation satellite dedicated to surface research and monitoring, on 23 July 1972, satellite data have become widely accessible. Their applications have long extended beyond single-purpose analysis or results (Wulder et al., 2022). With the continuous development of satellite observation, its immense potential for application in landslide research has become evident (Liu et al., 2021d). At present, satellite observation data mainly include space-borne Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) and optical remote sensing data, both of which are widely used as inputs for deep learning models in landslide identification.

Figure 1Data sources for potential landslide identification. Satellite observations (e.g., Landsat, Sentinel, SPOT, and Envisat) provide optical and radar imagery with varying spatial resolutions for detecting and mapping landslides. Airborne observations (LiDAR, UAV) deliver high-resolution topographic and photographic data, while ground-based observations (TLS, GBSAR, GNSS, rainfall and groundwater sensors) offer continuous in-situ monitoring of slope dynamics.

2.1.1 Space-borne SAR

SAR is an active microwave remote sensing system (Franceschetti and Lanari, 2018). It is not only capable of acquiring data on demand by actively emitting microwave signals but also facilitates partial penetration of vegetation cover through its longer wavelength bands (such as the L-band), thereby allowing the retrieval of surface deformation information beneath vegetated areas.

A critical operational advantage of SAR lies in its capacity to image regardless of illumination (day or night) and weather conditions (Koukiou, 2024). The continuous, unimpeded time series data this provides is essential for serving as input to deep learning models, allowing these models to be trained to identify long-term patterns of terrain change. For this reason, SAR is widely employed for the crucial task of continuous monitoring in high-risk environments, where cloud cover and the timing of a disaster are unpredictable.

Notably, the NASA-ISRO SAR Mission (NISAR), jointly developed by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO), was successfully launched in 2025 (Indian Space Research Organisation, 2025; NASA, 2025). The satellite carries both L-band and S-band SAR systems, enabling more precise and frequent measurements of surface deformation. With a revisit period of approximately 12 d, it delivers globally consistent coverage with a balanced spatial and temporal resolution. This capability provides researchers with abundant and continuous observations, supporting large-scale, high spatiotemporal resolution landslide early detection and dynamic monitoring.

Interferometric SAR (InSAR) has been developed based on the principle of measuring phase differences between two or more SAR images of the same area (Dai et al., 2022; Ma et al., 2023b; Zeng et al., 2024). By coherently processing these images, InSAR obtains high-precision surface elevation information and can be further applied to detect ground deformation.

In contrast, SAR mainly provide backscatter information of ground objects. Although some features of ground objects can be identified according to the scattering characteristics, their ability to obtain topographic elevation information is relatively weak. InSAR, on the other hand, can directly generate topographic elevation data, which is of great significance for analyzing the topography and geomorphology in the identification of potential landslides, and determining key elements such as the topographic undulation and slope of potential landslide areas.

When screening for potential landslides over a large area, InSAR has higher efficiency (Dun et al., 2021; Tang et al., 2025; Zhang et al., 2021). When monitoring large potential landslide areas such as mountainous regions, InSAR can quickly obtain topographic deformation information over a large area, promptly detect potential areas with potential landslides, and reduce the workload and blind spots of manual inspections.

Recent studies have integrated InSAR-derived deformation velocity fields with deep learning models to automatically detect slow-moving or latent landslides. For example, Liu et al. (2022d) employed an InSAR-CNN framework to map active landslides in the Eastern Tibet Plateau area, achieving a detection accuracy of over 90 %. Similarly, Zhang et al. (2022d) proposed a two-stage detection deep learning network (InSARNet) for detecting anomalous deformation areas in Maoxian County, Sichuan Province, with a recognition accuracy of 93.88 %. Targeting the complex deformation mechanisms of multi-type landslides in Zigui County, Three Gorges Reservoir Area, Hu et al. (2025b) used InSAR time-series displacement as the core data, develop a deep learning architecture based on the integrated framework of EMD and GRU, break through the limitations of conventional models such as single-type, single-target, and low-accuracy, and achieve dual-accurate prediction of displacement and failure time for multi-type landslides.

Differential InSAR (D-InSAR) is an advancement of InSAR that eliminates topographic phase through differential processing, focusing specifically on deformation information extraction (Shen et al., 2022). The emergence of D-InSAR not only enables the transition from mixed deformation-topography signals to pure deformation signal extraction but also extends its applicability from detecting discrete deformation events to identifying slow-moving landslide processes, significantly enhancing the reliability of landslide monitoring (Zhong et al., 2024).

2.1.2 Optical Remote Sensing

Optical remote sensing refers to the acquisition of surface information through sensors that measure reflected solar radiation. Its application in geological hazard investigations dates back to the 1970s (Fu et al., 2024; Liu and Wu, 2016).

Optical remote sensing offers high resolution, currently capable of achieving spatial resolutions as fine as 0.3 m or better. For example, Maxar's WorldView-3 delivers 0.31 m panchromatic imagery (Hu et al., 2016; Longbotham et al., 2014), while India's Cartosat-3 satellite achieves panchromatic imagery with a resolution of up to 0.25 m (Gupta et al., 2024). In potential landslide identification, it not only facilitates the retrieval of detailed surface textures and color characteristics using rich spectral data but also enables the direct identification of morphological features and object contours via visual interpretation of imagery (Cheng and Han, 2016; Li et al., 2022b; Ma and Wang, 2025).

Landslide formation typically follows a progressive process from deformation to failure, accompanied by precursor indicators such as tensile cracks, stepped scarps, and localized collapses. These indicators exhibit distinct spectral signatures in optical imagery compared to their surroundings, enabling both manual interpretation and automated detection. In deep learning applications, multispectral optical images have been widely used to train CNN-based models for potential landslide identification. Lu et al. (2023a) developed a method for achieving accurate landslide mapping using medium-resolution remote sensing images and DEM data, which has the potential for deployment in large-scale landslide detection. Jiang et al. (2022a) proposed a TL-Mask R-CNN for identifying a small number of old landslide samples in the area along the Sichuan-Tibet Transportation Corridor. The results show that the pixel accuracy of segmentation for new landslides and old landslides can reach 87.71 % and 75.86 % respectively.

In vegetated mountainous regions, surface vegetation often undergoes detectable changes before a landslide event. Optical remote sensing leverages multispectral data, particularly red and near-infrared bands, to monitor vegetation health and identify potential landslide zones (Coluzzi et al., 2025; Fiorucci et al., 2018). Furthermore, the calculation of the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) facilitates the evaluation of vegetation health in potential landslide regions, providing critical insights into potential landslide precursors (Verrelst et al., 2015).

However, the broad spectral bands of multispectral sensors limit their ability to detect more subtle, diagnostically specific precursory signals. The advancement beyond broad-band multispectral imaging to hyperspectral imaging has opened new avenues for landslide precursor detection (Kilgore and Restrepo, 2025; Ye et al., 2019). Hyperspectral sensors capture hundreds of contiguous spectral bands, enabling the identification of specific mineralogies (e.g., expansive clays like smectite that influence slope stability) and subtle geochemical alterations on slope surfaces. For instance, the shifting absorption features in the short-wave infrared region can signal changes in soil water content and mineral composition that often precede failure (Thimsen et al., 2017). The integration of these rich spectral datasets with deep learning architectures has significantly advanced automated landslide analysis (Huang et al., 2022c; Shahabi et al., 2021). These models excel at learning complex patterns from high-dimensional spectral-spatial information, enabling highly accurate detection of landslide scars and even precursory features like cracks and seepage zones that are otherwise challenging to identify.

While both space-borne SAR and optical remote sensing are pivotal for large-area landslide screening, they offer complementary capabilities and have distinct limitations. Optical remote sensing provides intuitive visual interpretation of geomorphological features but is rendered useless by cloud cover and darkness. In contrast, space-borne SAR, with its all-weather, day-and-night imaging capability, excels in detecting millimeter-to-centimeter-scale surface deformation through InSAR techniques, which is a direct precursor to landslide failure. However, InSAR performance can be degraded in heavily vegetated areas due to temporal decorrelation and in steep terrain due to geometric distortions (Lin et al., 2022; Yan et al., 2024), areas where optical stereo imaging for DEM generation might be less affected. Therefore, the integration of SAR-derived deformation maps and optical-based geomorphological maps is considered a best practice for regional-scale landslide inventory mapping and preliminary hazard assessment (Xun et al., 2022).

2.2 Airborne Remote Sensing Data

Airborne remote sensing data, typically acquired by manned aircrafts, provide high-resolution imagery of localized areas. Advanced airborne platforms equipped with oblique photogrammetry and, more recently, close-range photogrammetry technologies enable millimeter-level accuracy in 3D photogrammetry, facilitating the observation of subtle surface deformations, rock mass structures, and the construction of highly detailed 3D models of terrain and above-ground infrastructure (Macciotta and Hendry, 2021; Xu et al., 2023). Among these technologies, airborne photogrammetry and airborne radar are the most commonly used.

2.2.1 Airborne Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR)

LiDAR has been used for landslide and other geological hazard investigations in many regions since the late 1990s. As an active remote sensing system, LiDAR can laterally scan a range of 60° and capture 400 000 points per second, enabling large-scale 3D scanning of terrain, structures, and vegetation within a short period (Mallet and Bretar, 2009). It offers centimeter-level accuracy in both horizontal and vertical dimensions.

Airborne LiDAR is irreplaceable in capturing 3D details and penetrating vegetation, particularly in densely vegetated areas where conventional aerial photography faces significant limitations. Airborne LiDAR not only acquires high-resolution Digital Surface Models (DSMs) from laser point cloud data but also generates high-accuracy DEMs by removing vegetation contributions (Fang et al., 2022; Jaboyedoff et al., 2012; Yan et al., 2023), thereby revealing concealed hazard features such as mountain fractures, loose deposits, and landslide masses under vegetation cover.

Point cloud data obtained from airborne LiDAR can monitor dynamic changes in mountainous terrain by detecting deformations such as subsidence, displacement, and uplift, while also facilitating the construction of 3D landslide models to simulate sliding directions and impact areas. Through intuitive visualization of slope morphology and structure from multiple perspectives, LiDAR enables researchers to conduct a comprehensive assessment of slope conditions and identify subtle hazard features that may not be easily discernible in 2D imagery.

These high-precision DEMs and point clouds serve as critical inputs for deep learning models. For instance, Wei et al. (2023) proposed the Dynamic Attentive Graph Network (DAG-Net) model to construct dynamic edge features for enhancing point cloud representations, achieving the highest mean Intersection over Union (mIoU) of 0.743 and an F1-score of 0.786. Based on the advanced PointNet and PointNet architectures, Farmakis et al. (2022) developed deep neural networks for 3D point cloud learning. The best-performing model achieved accuracies of approximately 89 % and 84 % during the final and shortest monitoring campaigns, respectively. These examples demonstrate that airborne LiDAR data are not only suitable but have been effectively applied in deep learning-based landslide analysis.

2.2.2 Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV)

UAV aerial photogrammetry provides outstanding maneuverability and high-precision measurements. Traversing over steep slopes and valleys, UAVs are able to monitor areas that are often inaccessible to satellites and manned aerial platforms (Niethammer et al., 2012), thus addressing critical observational limitations.

In large-scale and topographically complex regions, UAVs can perform efficient aerial inspections, overcoming the limitations of ground-based inspections in inaccessible or visually obstructed regions. By rapidly scanning mountain slopes, embankments, and gullies, UAVs provide a comprehensive understanding of the geological conditions and enable timely identification of macro-scale geomorphic anomalies. However, given cost-effectiveness constraints, UAVs are currently more commonly used for periodic and continuous monitoring in localized areas. They are particularly well-suited for rapid and dynamic monitoring of landslides in high-priority zones.

With the rapid advancement of UAVs, centimeter-level vertical and oblique aerial photogrammetry is now achievable (Fan et al., 2020). The high-definition cameras mounted on UAVs are able to capture the subtle cracks on the surface of the mountain. These cracks may be early signs of a landslide (Sun et al., 2024a). By conducting a comparative analysis of the images taken at different times, the development and changes of the cracks can be monitored, including the increase in the length, width and depth of the cracks, as well as the changes in the crack orientation.

In some mountainous areas or valleys, there may be a large number of loose accumulations. These accumulations may trigger landslides under specific conditions. Aerial photography by UAVs can clearly identify information such as the distribution range, accumulation quantity and accumulation shape of these loose accumulations, and assess their potential threats to the surrounding environment. This capability is leveraged in deep learning applications, where time-series UAV imagery is processed using RNNs or 3D CNNs to monitor the spatiotemporal evolution of these cracks, providing a data-driven approach for early warning (Xu et al., 2025; Sandric et al., 2024).

Airborne platforms bridge the gap between satellite and ground-based observations. LiDAR is unparalleled in generating high-precision DEM, revealing concealed paleo-landslides and subtle topographic features critical for hazard mapping. However, its deployment is costly and logistically complex. UAVs, as a flexible and cost-effective alternative, have democratized high-resolution data acquisition. They can be equipped with various sensors (e.g., optical, multispectral, and even lightweight LiDAR) to conduct rapid response surveys following triggering events such as earthquakes or heavy rainfall (Han et al., 2023). While UAV-derived models have ultra-high resolution, their coverage is limited per sortie compared to airborne campaigns. The choice between them often involves a trade-off between coverage, cost, operational flexibility, and the specific requirement for vegetation penetration.

By equipping UAVs with LiDAR sensors to effectively remove vegetation from the data, this integrated approach combines the strengths of photogrammetry and LiDAR (Mandlburger et al., 2020; Wallace et al., 2012). It allows researchers to reveal landslide boundaries, crack patterns, and other deformation features hidden beneath vegetation cover, enabling rapid deployment and targeted area monitoring while mitigating vegetation-related challenges in landslide assessment.

2.3 Ground-based Observation Data

Satellite observation and airborne remote sensing are mainly employed for identifying potential landslides based on surface morphology. However, these approaches are often affected by vegetation cover, viewing geometry, and atmospheric noise, which may lead to misclassification or omission (Almalki et al., 2022; Dubovik et al., 2021). Therefore, ground-based observation techniques play a critical complementary role, offering higher temporal resolution, accuracy, and localized verification for potential landslide identification. In recent years, data collected from ground-based monitoring instruments have not only been used for field validation but also increasingly incorporated into deep learning frameworks to improve temporal continuity and physical interpretability in landslide detection and forecasting.

2.3.1 Ground-based Synthetic Aperture Radar (GB-SAR)

GB-SAR is an active ground-based microwave remote sensing system that has been developed over the past decade, effectively integrating the principles of SAR imaging with electromagnetic wave interferometry. By leveraging precise measurements of sensor system parameters, attitude parameters, and geometric relationships between orbits, GB-SAR quantifies spatial positions and subtle changes at specific surface points, allowing for the measurement of surface deformations with millimeter or even sub-millimeter precision.

Compared with spaceborne SAR, GB-SAR can adjust the incidence and azimuth angles of radar waves, thereby avoiding phase decorrelation caused by terrain-induced occlusion in spaceborne observations. Consequently, they are particularly suitable for monitoring steep slopes, canyons, and other areas with limited line-of-sight coverage from satellites (Noferini et al., 2007).

During landslide movement, the ground experiences noticeable subsidence, displacement, or cracking. GB-SAR can be configured for high-resolution, continuous observation to capture instantaneous deformations during the landslide creep phase and generate corresponding displacement maps (Liu et al., 2021a; Xiao et al., 2021). For example, Long et al. (2018) proposed a GBSAR persistent scatterer point selection method based on the mean coherence coefficient, amplitude dispersion index, estimated signal-to-noise ratio, and displacement accuracy index. Han et al. (2022) proposed an LSTM-based approach for processing GB-InSAR time series data.

For small-scale regional monitoring, GB-SAR can establish customized geometric configurations specifically designed for target areas. Utilizing mobile rail systems or multi-antenna setups, GB-SAR reconstructs 3D deformation vector fields of landslide masses (Shi et al., 2025), identifying sliding directions and potential failure surfaces.

2.3.2 Terrestrial Laser Scanning (TLS)

TLS emerged in the mid-1990s. It plays a unique role in local refined monitoring by emitting laser pulses and measuring their reflection time (Stumvoll et al., 2021; Teza et al., 2007).

The landslide often manifests as a sharp change in the ground surface. TLS can provide data with sufficient accuracy, assisting researchers in identifying the features of these landslides (Abellán et al., 2009; Teng et al., 2022).

By quickly and massively collecting spatial point position information, TLS can automatically splice and rapidly obtain the appearance of the measured object. It can be used to construct high-precision surface models and appearance models of buildings and structures. The 3D model can display the shape and structure of the mountain and the detailed features of the ground surface from different angles and in all directions (Zhou et al., 2024a), enabling geological experts and engineers to have a more intuitive understanding of the overall situation of the landslide area. For example, the cracks in the mountain, the loose accumulations, and the degree of weathering of the rocks can be clearly seen, providing richer information for the identification of potential landslide hazards.

In the context of deep learning, TLS-derived 3D point clouds have become critical inputs for morphological feature extraction and automatic landslide identification. For example, Senogles et al. (2022) integrated TLS point cloud data to assess surface displacements induced by landslide movements. Wang et al. (2025) provided a practical and adaptable solution for landslide monitoring by integrating TLS point clouds with embedded RGB imagery.

These examples confirm that TLS data are not only suitable but already actively used in deep learning-based landslide recognition, providing precise geometric constraints for multi-source fusion frameworks that combine DEM, optical, and InSAR information.

Ground-based techniques provide the highest precision for monitoring a specific slope of interest. GB-SAR and TLS are both non-contact remote sensing methods, but they operate on different principles. GB-SAR offers continuous, all-weather, mm-level deformation monitoring over a large area (several km2) from a single station, making it ideal for early warning. Its drawback is the need for a stable, opposing installation point with a clear line-of-sight (Monserrat et al., 2013). TLS, on the other hand, provides mm-to-cm-level 3D point clouds of the slope surface, excellent for quantifying volume changes and detailed geometric changes. However, it is typically used for periodic surveys rather than continuous monitoring and has occlusion shadows (Huang et al., 2019).

2.3.3 Ground-based Sensor Devices

Compared to the aforementioned data sources, ground-based sensors offer key advantages, including high precision, real-time capabilities, and multi-parameter fusion (Dai et al., 2023). They can address the limitations of remote sensing and provide critical ground-based dynamic information for potential landslide identification.

Ground-based sensing devices are highly diverse, and the data they acquire directly reflect the state of landslide masses. These datasets provide foundational inputs for deep learning models, enabling multi-dimensional analysis and interpretation of potential landslide conditions. For example, ground sensors (e.g., GNSS receivers and crack meters) can collect parameters like displacement and tilt angle at frequencies ranging from minutes to seconds, capturing transient, anomalous signals just prior to landslide events, thereby filling the temporal resolution gap in remote sensing (see Fig. 1). These data are often used as input sources for RNN models and their variants (Bai et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2021a). By integrating time series data with SAR imagery, deep learning models can be trained to uncover correlation patterns between surface deformations and subsurface parameters (Jiang et al., 2022b). Instruments such as piezometers and soil pressure gauges can directly monitor key parameters like pore water pressure and soil stress on the sliding surface. By combining the obtained subsurface data with geomechanical equations, the position of the sliding surface or geotechnical strength parameters can be inferred.

Therefore, GB-SAR, TLS, and ground-based sensors are not only auxiliary observation techniques but are increasingly serving as key data sources for deep learning-driven landslide identification. Their integration into CNN, LSTM, and Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) frameworks enables high-resolution spatial-temporal modeling of slope behavior, bridging the gap between field-scale monitoring and large-scale hazard prediction.

2.4 Summary of Data Source for Potential Landslide Identification

In summary, no single data source is sufficient for a comprehensive potential landslide identification framework. Regional-scale satellite data, particularly InSAR, is optimal for the early detection of pre-landslide deformations over vast areas. Airborne platforms, such as UAVs, then provide high-resolution optical and LiDAR data to characterize the precise geometry and activity of identified potential landslides. Finally, ground-based and in-situ sensors enable site-specific, real-time monitoring of high-risk slopes, validating remote sensing findings and supporting early warning systems. The strategic integration of these multi-platform data is crucial for transitioning from regional screening to mechanistic understanding and risk mitigation.

Beyond these general data modalities, recent years have also witnessed the emergence of benchmark datasets that serve as standardized testbeds for developing and evaluating deep learning methods in landslide identification. Such datasets are essential for ensuring reproducibility, enabling fair comparison across models, and accelerating methodological advances. Representative examples include the CAS Landslide Dataset, a large-scale, multi-sensor dataset explicitly designed for deep-learning-based landslide mapping (Xu et al., 2024); the Landslide4Sense (L4S) benchmark, developed within an international competition, which provides multi-source satellite image patches (Ghorbanzadeh et al., 2022b); and the Diverse Mountainous Landslide Dataset (DMLD), which emphasizes high-resolution instances from complex mountainous terrains (Chen et al., 2024a). In addition, slope-unit-based benchmark datasets have been constructed to support susceptibility mapping and regional-scale comparisons (Martinello et al., 2021).

These datasets serve as valuable resources for pixel-level segmentation and slope-unit-based susceptibility modeling. However, in practice, the compilation of landslide inventories faces considerable challenges, making it difficult to obtain comprehensive and accurate records (Kong et al., 2025; Lee et al., 2018). Consequently, data scarcity remains a common issue in landslide hazard identification, particularly in remote regions or areas with limited accessibility. Therefore, it is necessary to further expand their geographical coverage and establish standardized evaluation protocols.

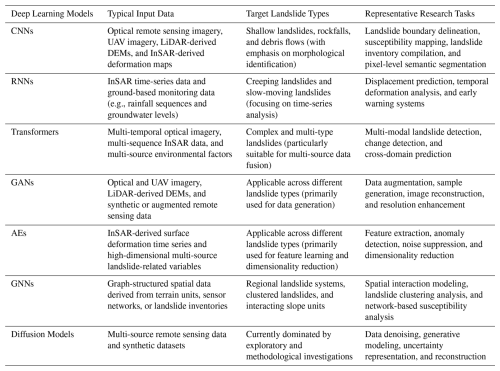

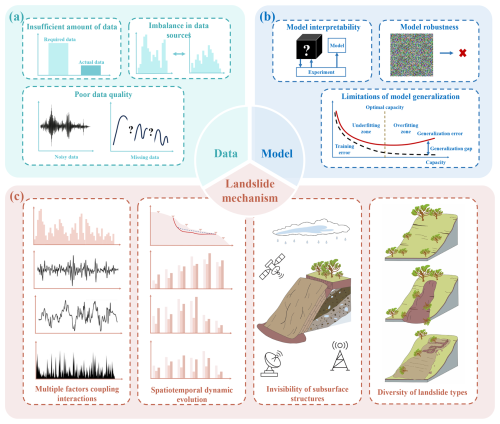

The effectiveness of deep learning in potential landslide identification largely depends on selecting an appropriate model architecture suited to the data type and specific task. While all deep learning models excel at automated feature extraction, their internal architectures predispose them to excel in different aspects of the overall workflow. Therefore, this section does not merely list models, but organizes them based on their primary function in the potential landslide identification pipeline. We analyze several commonly used deep learning models by categorizing them into five functional roles: image analysis and processing, time series analysis, data generation, anomaly detection, and data fusion.

3.1 Models for Image Analysis and Processing in Potential Landslide Identification

Image data plays a critical role in potential landslide identification, especially through remote sensing, satellite, and UAV imagery. These images enable the acquisition of large-scale terrain data, encompassing complex geographical features, vegetation coverage, and ground fissures, which often serve as potential precursors to landslide occurrences. The adoption of deep learning has facilitated a shift from conventional manual visual interpretation to automated high-precision segmentation.

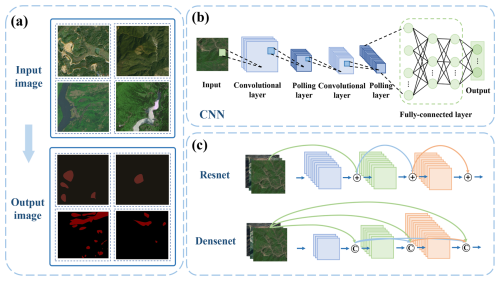

CNNs, owing to their inherent capability to learn hierarchical and multi-scale spatial features (Kattenborn et al., 2021; LeCun et al., 1998; Liu et al., 2022b), have become the core methodological framework for most image-based deep learning applications in landslide research (see Fig. 2). This capability directly addresses a long-standing limitation of conventional classifiers, which struggle to simultaneously capture fine-scale precursors (e.g., narrow ground fissures) and large-scale landslide morphology within a unified framework. Multi-scale convolutional feature extraction has been shown to significantly enhance the sensitivity of landslide detection across a wide range of spatial extents (Hussain et al., 2019; Shi et al., 2020; Yao et al., 2021). For example, small convolutional kernels are particularly effective in identifying subtle surface disturbances, such as localized soil texture variations and ground cracks, which often precede slope failure. Hamaguchi et al. (2018) and Wang et al. (2024a) demonstrated that CNN-based models can detect extremely small and subtle features, including cracks as narrow as 0.05 m, a level of detail that is difficult to achieve using conventional texture-based methods.

Figure 2Functional pipeline of CNN-based models for image analysis and processing. (a) Semantic mapping process: demonstrating the transition from optical input to binary classification for target identification. (b) Segmentation performance: visualizing the model's capability to delineate precise landslide boundaries (binary masks) from optical imagery. (c) Optimization strategies: comparing skip-connections and dense connectivity for enhancing gradient flow and feature reuse.

Conversely, larger convolutional kernels and multi-scale fusion strategies enhance the identification of overall landslide morphology and scar boundaries, which are critical for accurate inventory mapping. Ding et al. (2022) showed that larger kernels improve the shape bias of CNNs, facilitating the recognition of large-scale structural patterns, while Li et al. (2025b) demonstrated that scale-adaptive kernel fusion improves global perception of landslide extents and contextual background information. By integrating multi-scale feature extraction within a single model, CNN-based approaches outperform conventional machine-learning classifiers that depend on fixed-scale descriptors and often exhibit reduced generalization in heterogeneous terrain.

Beyond feature extraction, architectural innovations such as residual and dense connections have substantially improved the trainability and data efficiency of deep networks in landslide applications (He et al., 2016). Deep networks with increased depth generally exhibit stronger representational capacity but are prone to optimization difficulties and overfitting, particularly under limited training samples (Ebrahimi and Abadi, 2021).

Residual Networks (ResNet) address these challenges through shortcut connections (Qi et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2022), enabling stable training of very deep models and improved discrimination between landslide scars and surrounding vegetation or bare soil in complex terrains (see Fig. 2). However, deeper architectures also incur higher computational costs, which may constrain their practical deployment in large-scale or near-real-time mapping scenarios (Hasanah et al., 2023).

Dense Convolutional Networks (DenseNet) further enhance feature reuse and gradient flow through dense connectivity, reducing parameter redundancy and improving performance under limited training data conditions (Huang et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2021c). This property is particularly relevant for landslide studies, where high-quality labeled samples are often scarce and spatially clustered. Empirical studies indicate that DenseNet-based models can effectively extract multi-scale landslide features in complex terrain while maintaining computational efficiency (Cai et al., 2021; Li et al., 2021a; Ullo et al., 2021).

With the maturation of CNN backbones, semantic segmentation has emerged as the dominant paradigm for landslide detection, as it enables dense, pixel-level delineation of landslide extents that is essential for inventory construction and hazard assessment (Guo et al., 2018; Lu et al., 2023b; Zhou et al., 2024b). Among these models, U-Net and its variants have become benchmarks due to their encoder–decoder structure and skip connections, which preserve spatial detail and improve boundary delineation (Chandra et al., 2023; Chen et al., 2022; Meena et al., 2022; Ronneberger et al., 2015). U-Net-based models have demonstrated strong performance in challenging conditions, such as cloud-covered or topographically complex regions using SAR imagery (Nava et al., 2022).

However, U-Net's relatively limited receptive field can restrict its ability to capture long-range contextual information in heterogeneous geological settings. DeepLab addresses this limitation by incorporating dilated convolutions and Atrous Spatial Pyramid Pooling (ASPP), enabling effective fusion of local texture and global contextual cues without sacrificing spatial resolution (Chen et al., 2017; Huang et al., 2024). This multi-scale contextual modeling has been shown to reduce false positives and improve detection consistency in geologically complex environments, highlighting a key advantage of advanced deep segmentation models over simpler pixel-based or object-based approaches (Niu et al., 2018; Sandric et al., 2024).

Beyond static mapping, deep learning also facilitates multi-temporal change detection and dynamic hazard monitoring. By comparing segmentation outputs across time or directly processing multi-temporal image stacks, CNN-based models can characterize the spatial evolution of landslides and identify active deformation zones (Amankwah et al., 2022). Wang (2023) demonstrates that 3D CNNs enable joint modeling of spatial and temporal dependencies, producing both change hotspot maps and temporal evolution curves that capture landslide initiation and progression. Some studies even have integrated attention mechanisms into conventional CNN architectures to enhance the analysis of multi-temporal remote sensing imagery, thereby enabling the identification of landslide hazard evolution over time. For example, Meng et al. (2024) proposed a framework based on CNN and optimized Bidirectional Gated Recurrent Unit (BiGRU) with an attention mechanism, designed to forecast landslide displacement with a step-like curve. Dong et al. (2022) proposed L-Unet which combines multi-scale feature fusion with attention modules to improve landslide segmentation performance, particularly at boundaries.

Overall, image-based deep learning models represent a substantial methodological advance over traditional machine-learning classifiers in terms of multi-scale feature representation, mapping completeness, and robustness to complex backgrounds. Nevertheless, their performance remains contingent on data quality, sample representativeness, and computational resources, and they generally lack the explicit physical interpretability of process-based models. These limitations motivate increasing interest in hybrid framework.

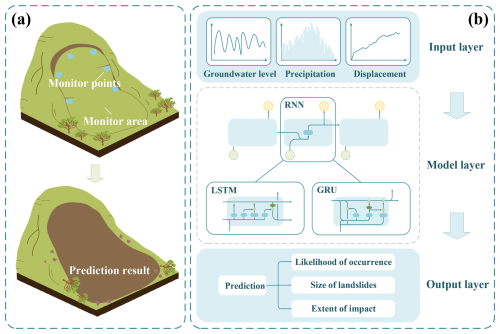

3.2 Models for Time Series Analysis in Potential Landslide Identification

Landslide occurrence is inherently a time-dependent process, driven by the cumulative and often delayed effects of environmental forcing such as rainfall, groundwater fluctuation, reservoir operation, and seismic disturbance. Time series data describing slope displacement, pore-water pressure, rainfall intensity, or surface deformation provide critical information for identifying potential instability and forecasting landslide evolution. Unlike static susceptibility mapping, time series analysis directly targets the dynamic behavior of slopes and therefore plays a central role in early warning and short-term prediction (see Fig. 3).

Conventional statistical and physically based approaches have been widely used to analyze landslide-related time series. Statistical models typically assume linear or weakly nonlinear relationships and often require strong prior assumptions, while physically based models rely on simplified representations of hydromechanical processes and detailed parameterization that is difficult to obtain at scale. Deep learning-based temporal models offer a complementary data-driven alternative by automatically learning nonlinear dependencies, cumulative effects, and delayed responses directly from observations, without requiring explicit process equations.

RNNs represent the earliest class of deep learning models designed for sequential data, enabling the modeling of short-term temporal dependencies through recursive information flow (Elman, 1990; Ngo et al., 2021; Zaremba et al., 2014). In landslide studies, RNNs have been applied to displacement time series influenced by rainfall and groundwater variation, demonstrating their ability to capture short-term deformation trends prior to failure (Chen et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2022c). However, standard RNNs often struggle with long-term dependencies and cumulative effects, which are common in landslide processes driven by prolonged or intermittent forcing (see Fig. 3).

Figure 3Analytical framework of RNN-based models for time series analysis. (a) From field monitoring to predictive insight: outlining the transformation of multi-source field monitoring data into predictive landslide intelligence. (b) Processing temporal dependencies: illustrating the recursive logic of RNN, LSTM, and GRU in processing sequential variables.

To overcome the vanishing gradient problem inherent in RNNs, LSTM introduces memory cells and gating mechanisms that selectively retain relevant temporal information (Graves, 2012; Landi et al., 2021; Sherstinsky, 2020; Smagulova and James, 2019; Staudemeyer and Morris, 2019; Yu et al., 2019). This capability is particularly well aligned with landslide dynamics, where delayed and cumulative responses to rainfall or reservoir level fluctuations are critical precursors of instability. Empirical studies consistently demonstrate that LSTM-based models outperform conventional regression and shallow machine-learning approaches in displacement prediction and early warning tasks. For example, Yang et al. (2019) analyzed the relationships among landslide deformation, rainfall, and reservoir water levels, and found that compared with static models, the LSTM approach more accurately captured the dynamic characteristics of landslides and effectively leveraged historical information. Xu and Niu (2018) used a LSTM model to predict the displacement evolution of the Baijiabao landslide using rainfall and hydrological level data, achieving a higher correlation compared with traditional regression models. In another study focused on shallow landslides, Xiao et al. (2022) used a week-ahead LSTM model, which exhibited stable performance and improved prediction accuracy in short-term prediction scenarios. Additionally, Gidon et al. (2023) constructed a Bi-LSTM model and achieved a detection accuracy of 93 % in the Mawiongrim area.

Despite their strong performance, LSTM models are computationally demanding and may be prone to overfitting when training data are limited. GRUs provide a streamlined alternative by simplifying the gating structure while maintaining comparable predictive accuracy (Cho et al., 2014). This balance between model complexity and performance makes GRU-based models particularly attractive for real-time landslide monitoring and operational early warning systems, where computational efficiency and rapid updating are critical (Chung et al., 2014; Rawat and Barthwal, 2024; Zhang et al., 2022e). Recent studies indicate that GRUs can effectively identify acceleration phases in displacement time series, enabling earlier detection of rainfall- or earthquake-induced slope instability (Chang et al., 2025; Yang et al., 2025).

More recently, Transformer-based architectures have emerged as powerful alternatives for time series modeling by leveraging self-attention mechanisms to capture long-range temporal dependencies in parallel (Vaswani et al., 2017). Compared with recurrent models, Transformers are particularly effective at modeling long-term and non-local temporal relationships, which are often present in landslide processes influenced by multi-seasonal rainfall or complex hydrological regimes. In landslide-related applications, Transformers can adaptively learn latent temporal features across diverse scenarios and outperform conventional RNN-based models in capturing complex temporal patterns (Esser et al., 2021; Huang and Chen, 2023; Wang et al., 2024b; Zerveas et al., 2021).

However, a key drawback of the standard Transformer is its quadratic computational complexity with respect to sequence length, which becomes prohibitive for very long sequences (Zhuang et al., 2023). This also complicates the interpretation of how the model extracts features and makes decisions from large amounts of landslide data, posing challenges for practical deployment. It is worth noting that mitigating this quadratic complexity is an active research area, with many efficient Transformer variants being developed. For example, Zhao et al. (2024f) combined the strengths of CNN and Transformer architectures, selecting and analyzing nine landslide-conditioning factors to successfully achieve accurate landslide localization and detailed feature capture. Ge et al. (2024) proposed the LiteTransNet model based on the Transformer framework, effectively capturing and interpreting the varying importance of historical information during the prediction process. Therefore, while powerful, the vanilla Transformer may not be the optimal choice for all practitioners, and its computational demands should be carefully considered.

In summary, deep learning-based time series models represent a significant advancement over conventional statistical approaches by enabling data-driven learning of nonlinear, delayed, and cumulative deformation patterns that are difficult to encode explicitly in physical models. RNNs and LSTMs remain effective and interpretable for short- to medium-term prediction tasks, while GRUs offer computationally efficient solutions for operational systems (Li et al., 2021b; Wang et al., 2020b). Transformer-based models provide superior capacity for long-term dependency modeling but require careful consideration of data availability, computational resources, and interpretability. These trade-offs highlight the importance of selecting temporal architectures based on specific monitoring objectives, data characteristics, and operational constraints.

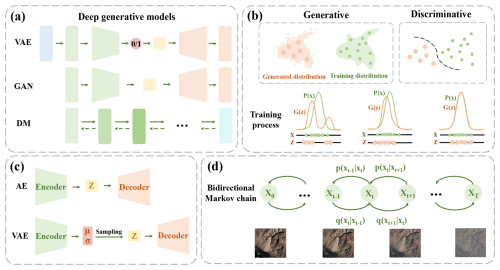

3.3 Models for Data Generation in Potential Landslide Identification

A fundamental challenge in potential landslide identification lies in the scarcity, imbalance, and spatial clustering of labeled landslide samples. Landslide inventories are often incomplete, biased toward large or easily detectable events, and unevenly distributed in space and time. These limitations significantly constrain the performance and generalization ability of both traditional machine-learning classifiers and deep learning-based models, particularly in data-hungry settings. Data generation aims to alleviate these issues by learning the underlying data distribution and synthesizing new samples that are statistically consistent with observed landslide patterns (Kingma et al., 2014; Moreno-Barea et al., 2020; Shorten and Khoshgoftaar, 2019).

Conventional data augmentation techniques (e.g., rotation, flipping, noise injection) provide limited diversity and do not fundamentally address class imbalance or morphological variability in landslide datasets. Deep generative models represent a major methodological advance by explicitly modeling the latent distribution of geospatial features, thereby enabling the creation of realistic and diverse synthetic landslide samples (Alam et al., 2018; Karras et al., 2020; Ma et al., 2024; Xu et al., 2015). Unlike discriminative models, generative models capture probabilistic representations of terrain, deformation, or image features, making them particularly suitable for addressing uncertainty, rarity, and heterogeneity in landslide data. Commonly used deep generative models include GANs, Variational Autoencoders (VAEs), and diffusion models (see Fig. 4).

GANs are among the most widely adopted generative models for landslide-related data augmentation, particularly in remote sensing imagery. Through adversarial training between a generator and a discriminator, GANs can produce visually realistic synthetic samples that closely resemble real landslide images (Goodfellow et al., 2014; Gui et al., 2021; Saxena and Cao, 2021). In potential landslide identification, this capability can address the shortage of labeled image samples that limits the performance of segmentation and classification models. For example, Feng et al. (2024) achieved the first implementation of using a GAN to generate synthetic high-quality landslide images, aiming to address the data scarcity issue that undermines the performance of landslide segmentation models. Al-Najjar and Pradhan (2021) proposed a novel approach that employs a GAN to generate synthetic inventory data. The results indicate that additional samples produced by the proposed GAN model can enhance the predictive performance of Decision Trees (DT), Random Forest (RF), Artificial Neural Network (ANN), and Bagging ensemble models.

Despite their effectiveness, GAN-based approaches exhibit notable limitations. Mode collapse may reduce sample diversity, particularly for rare landslide types or extreme morphologies, and training instability often necessitates careful hyperparameter tuning and substantial computational resources (Fang et al., 2020). Such constraints can limit their applicability in operational or real-time hazard assessment. Recent architectural refinements, including Conditional GAN (CGAN) (Kim and Lee, 2020; Loey et al., 2020; Mirza and Osindero, 2014), image-to-image translation with GAN (Pix2Pix) (Isola et al., 2017; Qu et al., 2019), and Wasserstein GAN (WGAN) (Arjovsky et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2019), partially mitigate these issues by improving training stability and enabling conditional or controlled sample generation. As a result, GANs are increasingly viable for high-resolution landslide image synthesis and remote sensing–based susceptibility analysis, particularly when visual realism is a primary requirement.

As a probabilistic variant of AEs, VAEs introduce latent-space regularization through variational inference (see Fig. 4). Compared with GANs, VAEs prioritize distributional coverage and uncertainty representation over visual sharpness (Hinton and Salakhutdinov, 2006; Kingma and Welling, 2013), making them well suited for probabilistic modeling of landslide processes. For instance, Cai et al. (2024) demonstrated that a VAE-GRU framework can generate narrow predictive intervals while maintaining high coverage probabilities, representing a substantial improvement over the state-of-the-art methods. Such probabilistic outputs are particularly valuable for risk-informed decision-making and early warning applications (Islam et al., 2021; Oliveira et al., 2022).

Figure 4Comparative mechanisms of deep generative models for data generation. (a) Contrasting fundamental training objectives: VAE (maximizing variational lower bounds), GAN (adversarial gaming), and Diffusion models (iterative noise reversal). (b) Adversarial learning: function of the generator-discriminator competition in improving sample fidelity. (c) Latent space modeling: highlighting the probabilistic sampling layer in VAEs that enables diverse sample generation compared to standard AEs. (d) Iterative denoising: the mechanism of reconstructing high-resolution imagery through reverse diffusion.

Compared with GANs, VAEs produce more diverse but slightly less detailed samples, due to their structured latent space constraints. This characteristic is particularly beneficial for exploring a wide range of potential landslide morphologies and for augmenting training datasets used in susceptibility prediction. However, VAEs may still struggle with highly imbalanced datasets, as their probabilistic reconstruction tends to favor majority classes. Integrating VAEs with stratified sampling or cost-sensitive learning could help overcome this limitation and further enhance landslide prediction performance.

When computational resources and training time permit, diffusion models provide a powerful alternative for generating high-quality, diverse, and stable data (Croitoru et al., 2023; Ho et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2023a; Zhu et al., 2023a). These models learn the data distribution by gradually adding noise to real samples (forward diffusion) and then reconstructing clean data through a reverse denoising process (see Fig. 4). The resulting models can sample new, realistic data points that reflect complex terrain and geophysical variability. For example, Lo and Peters (2024) proposed a Terrain-Feature-Guided Diffusion Model (TFDM) to fill gaps in DEM data. Similarly, Zhao et al. (2024b) employed a Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Model (DDPM) conditioned on incomplete DEMs, which serves as a transitional kernel during diffusion reversal to progressively reconstruct sharp and accurate DEM.

Despite their successful applications in image synthesis, denoising, and remote-sensing image enhancement (Leher et al., 2025; Sui et al., 2024; Xiao et al., 2023; Zou et al., 2024), diffusion models have not yet been widely applied directly to the identification of potential landslides and remain in the exploratory stage. Nonetheless, our optimism for their application is grounded in their potential to address key challenges such as limited labeled data through generative augmentation and, more importantly, to provide uncertainty quantification in predictions, which is vital for risk assessment.

In summary, deep generative models provide an essential complement to discriminative deep learning and conventional machine-learning approaches in potential landslide identification. Among them, GANs are effective for generating visually realistic imagery and data augmentation; VAEs capture probabilistic geomorphic transitions; and diffusion models ensure stability and fidelity in high-resolution terrain synthesis. Rather than replacing predictive models, generative approaches primarily enhance data quality, diversity, and uncertainty representation, thereby strengthening the robustness and generalization of landslide identification and forecasting frameworks.

3.4 Models for Anomaly detection in Potential Landslide Identification

Anomaly detection provides a complementary perspective to supervised landslide classification by focusing not on what constitutes a landslide, but on when and where a slope begins to deviate from its normal state. In potential landslide identification, this paradigm is particularly valuable because catastrophic failures are often preceded by subtle, progressive, and spatially heterogeneous signals. Typical anomalies include unexpected acceleration in surface displacement, coherence loss in InSAR observations, or irregular fluctuations in multi-sensor monitoring data, which may emerge well before visible slope failure (Deijns et al., 2020; Jiang et al., 2020).

Compared with conventional anomaly detection approaches based on empirical thresholds or predefined statistical rules, deep learning-based methods offer a critical advantage: they can learn complex, nonlinear “normality patterns” directly from data, without requiring explicit assumptions about failure modes. This shift is especially important in landslide-prone environments, where background variability driven by rainfall, vegetation dynamics, and sensor noise often masks early instability signals. By modeling high-dimensional spatiotemporal dependencies, deep learning enables a more adaptive and context-aware identification of abnormal slope behavior.

AEs constitute the most widely adopted framework for unsupervised anomaly detection in landslide monitoring. Rather than explicitly detecting failures, AEs are trained to reconstruct normal system states, such as stable slope displacement time series or radar backscatter signatures (Sakurada and Yairi, 2014; Zhou and Paffenroth, 2017). When exposed to abnormal inputs (such as sudden deformation acceleration or coherence degradation) the reconstruction error increases, providing an implicit indicator of potential instability. This reconstruction-based logic is particularly attractive in landslide applications, where labeled failure data are scarce or incomplete. For instance, Shakeel et al. (2022) developed an InSAR deformation anomaly detector based on an AE-LSTM architecture. Experimental analyses using synthetic deformation test scenarios achieved an overall performance accuracy of 91.25 %.

However, deterministic AEs implicitly assume that “normal” patterns can be represented by a single compact manifold, which may be insufficient for landslide systems characterized by multiple deformation regimes. VAEs address this limitation by explicitly modeling uncertainty in the latent space through probabilistic inference (Kumar et al., 2024; Pol et al., 2019). By learning a distribution rather than a single representation of normal slope behavior, VAEs are better suited to capture the intrinsic variability of environmental and geotechnical conditions (Kingma and Welling, 2013; Li et al., 2020; Park et al., 2018). Recent studies indicate that VAEs outperform conventional AEs when anomaly detection involves multivariate inputs combining displacement, rainfall, and hydrological factors, enabling a more robust identification of transitional instability stages (Nawaz et al., 2024; Han et al., 2025). Nevertheless, the probabilistic nature of VAEs also introduces practical challenges, including higher data requirements and the need for operationally meaningful thresholding strategies.

GANs offer an alternative perspective on anomaly detection by exploiting the discriminator's ability to differentiate between learned “normal” patterns and unfamiliar inputs (Kang et al., 2024; Xia et al., 2022). In landslide monitoring, GAN-based approaches learn the distribution of stable slope features, while deviations from this distribution are interpreted as anomalies (Radoi, 2022). Extensions such as AnoGAN further adapt this adversarial framework by explicitly embedding anomaly scoring mechanisms into the latent space (Lin et al., 2023; Thomine et al., 2023). While GAN-based methods have shown promise in detecting subtle deviations in complex data distributions, their training instability and sensitivity to hyperparameters remain practical limitations, particularly for operational early-warning systems.

Temporal models, including RNNs, LSTMs, and GRUs, play a distinct yet complementary role in anomaly detection by emphasizing when abnormal behavior emerges. These models learn expected temporal evolution patterns in displacement or rainfall time series and flag deviations from predicted trajectories (Zamanzadeh Darban et al., 2024; Zhang et al., 2022a). In landslide early-warning scenarios, this temporal sensitivity is crucial for identifying acceleration phases rather than static anomalies. Hybrid architectures that integrate temporal models with AEs or GANs further enhance anomaly detection by jointly capturing spatial reconstruction errors and temporal inconsistencies, enabling multi-source consistency checks across monitoring networks. For instance, Geiger et al. (2020) demonstrated a growing trend of utilizing LSTM networks as both the generator and discriminator within GAN frameworks for time-series anomaly detection. Similarly, Whitaker (2023) illustrated the application of LSTM-GAN architectures in identifying temporal anomalies.

Deep learning-based anomaly detection shifts landslide identification from static classification toward dynamic state monitoring, making it particularly suitable for early recognition of slope instability under evolving environmental conditions. Although these methods do not directly predict landslide occurrence, they provide an essential early-warning layer by highlighting abnormal system behavior that warrants further physical interpretation or intervention.

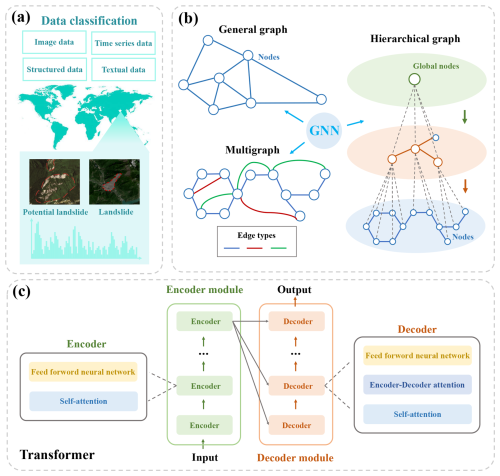

3.5 Models for Data Fusion in Potential Landslide Identification

In practical applications, the identification of potential landslide hazards is a complex task that influences by multiple factors (Zhang et al., 2018). These factors are often reflected through different data sources. We can roughly divide heterogeneous data into four categories: image data, time series data, structured data, and textual data. Given this heterogeneity, data fusion is essential for the accurate identification of potential landslides (see Fig. 5).

Figure 5Integrated framework of GNNs and Transformers for data fusion. (a) Multi-source integration: the architectural flow for synthesizing heterogeneous datasets (spatial images, time-series, and structured data) to support robust decision-making. (b) Topology modeling: GNN mechanisms designed to aggregate spatial dependencies across general, multi-graph, and hierarchical slope networks. (c) Global contextual attention: the Transformer architecture utilizing self-attention mechanisms to capture long-range dependencies in sequence-based or flattened spatial features.

Conventional data fusion approaches in landslide studies (such as feature concatenation, weighted linear combination, or statistical multivariate analysis) generally rely on predefined assumptions regarding variable independence or linear interactions. While these methods are computationally efficient, they struggle to capture the nonlinear, scale-dependent, and cross-modal relationships that characterize real-world landslide processes. In contrast, deep learning-based data fusion models provide a data-driven means to automatically learn high-order feature interactions across heterogeneous inputs, thereby offering a more flexible and expressive framework for potential landslide identification.

Among existing architectures, Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) have attracted increasing attention due to their ability to explicitly represent non-Euclidean spatial relationships. Landslide-related terrain units (e.g. slope units, grid cells, or monitoring stations) are inherently interconnected through topography, hydrological pathways, and geological continuity (see Fig. 5). Conventional CNN-based fusion models, which operate on regular grids, are limited in capturing such irregular spatial dependencies. By contrast, GNNs represent spatial entities as nodes and their geospatial, hydrological, or geological relationships as edges, enabling the propagation of information across topologically connected units (Scarselli et al., 2008; Ying et al., 2018; Zeng et al., 2022).

In landslide identification and forecasting, this graph-based representation allows geomorphic and hydrological signals to be explicitly transmitted between adjacent or functionally connected units, thereby better reflecting slope interaction mechanisms. For example, Kuang et al. (2022) proposed an innovative landslide forecasting model based on GNNs, in which graph convolutions are employed to aggregate spatial correlations among different monitoring sites. Ren et al. (2025) introduced a novel GNN framework with conformal prediction (GNN-CF) for landslide deformation interval forecasting, addressing the limitations of conventional models in handling predictive uncertainty.

According to the differences in message passing and aggregation methods, GNNs have derived various variants. For example, Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) is generated by generalizing the convolutional operation to graph-structured data (Kipf and Welling, 2016; Sharma et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2020a), and Graph Attention Network (GAT) dynamically weights the importance of neighboring nodes by introducing the attention mechanism (Veličković et al., 2017; Yuan et al., 2022; Zhou and Li, 2021). The emergence of these new architectures makes GNN variants more targeted than conventional GNNs and suitable for modeling heterogeneous relationships. Currently, they are often used for weighted analysis of the impacts of different geographical factors on landslides (Kuang et al., 2022; Li et al., 2025d; Zhang et al., 2024e).

Beyond graph-based models, Transformer architectures have emerged as a unifying framework for multimodal data fusion in landslide studies. As highlighted in Sect. 3.2, the Transformer's self-attention mechanism and modular architecture make it a universal framework for processing sequential data and enabling multimodal fusion (see Fig. 5).

In this context, the core advantage of the Transformer lies in its ability to integrate diverse input data (e.g., satellite imagery, GPS time series, and geological maps). It achieves this by employing independent embedding layers to convert each modality into a unified vector representation, which is then fused through the self-attention mechanism. This mechanism computes the interactions and correlations among all elements across different modalities, thereby enabling the model to capture cross-modal dependencies and extract joint feature representations within a unified framework. This capability makes the Transformer particularly suitable for landslide studies (Li et al., 2025c). For example, Piran et al. (2024) enhanced short-term precipitation forecasting by applying transfer learning with a pre-trained Transformer model. Zhang et al. (2024e) incorporated Transformer modules to build a graph-Transformer model that integrates global contextual information for the generation and analysis of Landslide Susceptibility Maps (LSMs).

In conclusion, deep learning-based data fusion provides a flexible and unified framework for integrating heterogeneous landslide-related data, including spatial, temporal, and topological information. By enabling joint representation learning across multiple data modalities, fusion-oriented architectures such as GNNs and Transformers have substantially enhanced the capability of potential landslide identification to capture complex environmental interactions that cannot be adequately represented by single-source or loosely coupled models. As a result, data fusion has become a critical methodological component in contemporary deep learning-based landslide hazard studies.

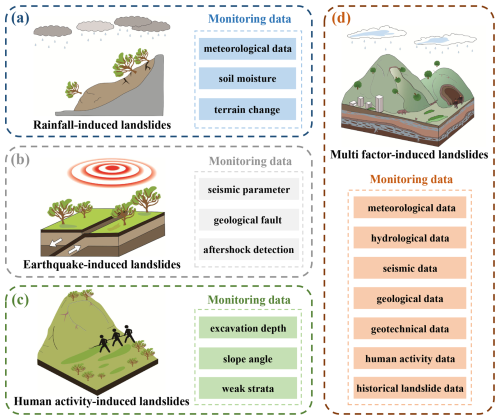

The preceding sections have laid the groundwork by discussing the data prerequisites and model architectures fundamental to deep learning in potential landslide research. Building upon that foundation, this section turns to the practical applications of deep learning for identifying potential landslides across diverse real-world scenarios.

Given that landslides are triggered by different dominant factors, the mechanisms, data characteristics, and monitoring strategies vary substantially among different types. To provide a systematic and targeted analysis, this section organizes the applications according to four major triggering categories: rainfall-induced landslides, earthquake-induced landslides, human activity-induced landslides, and multi-factor-induced landslides (see Fig. 6). For each category, we briefly outline its geological characteristics, summarize representative deep learning applications, and discuss model adaptability and monitoring considerations. This structure allows for a comprehensive understanding of how deep learning frameworks can be tailored to the unique challenges posed by different landslide-inducing mechanisms.

Figure 6Selection of monitoring data for different types of landslides (a) Rainfall-induced landslides. (b) Earthquake-induced landslides. (c) Human activity-induced landslides. (d) Multi-factor-induced landslides.

4.1 Application of Deep Learning in the Identification of Rainfall-induced Landslides

Rainfall stands as the predominant global trigger for landslides. Intense and short-duration rainfall events (lasting from a few hours to several days) often induce shallow landslides (Ma and Wang, 2024), whereas prolonged rainfall (lasting from several weeks to months) can lead to deeper and larger landslides, with depths ranging from 5 to 20 m (Casagli et al., 2023). Consequently, rainfall intensity, cumulative precipitation, and rainfall duration constitute critical triggering parameters for rainfall-induced landslides (Mondini et al., 2023).

Sustained or intense rainfall elevates slope unit weight and moisture content, alters pore water pressure regimes, and reduces shear strength via the principle of effective stress, thereby initiating surface instability. This hydro-mechanical coupling establishes a pronounced positive correlation between rainfall patterns and slope deformation (Li et al., 2022a).

Temporally, landslides exhibit both abrupt failure and delayed responses to rainfall. Pre-existing fractures act as preferential pathways for rainwater infiltration, yet the time required for percolation to reach slip zones introduces a hysteresis effect in slope deformation relative to precipitation events (Jiang et al., 2023; Liu et al., 2022c). During wet seasons, intense rainfall elevates groundwater tables, inducing fully saturated conditions in slope materials. This saturation amplifies shear strain rates, triggering rapid acceleration of landslide movement. Post-rainfall, groundwater levels remain elevated for extended periods (weeks to months), resulting in sustained but decelerated sliding velocities rather than complete stabilization. Consequently, despite concentrated rainfall during wet seasons, numerous landslides occur in subsequent dry periods (Ren et al., 2023), highlighting the delayed destabilization governed by lingering pore pressure dynamics. The hysteresis phase reflects progressive energy accumulation toward critical thresholds, while abrupt failure signifies rapid energy release during instability. This transition is typically characterized by a near-instantaneous shift from stable to unstable states when pore water pressures or soil moisture content exceed critical thresholds, with minimal intermediate deformation phases.

The spatial clustering of rainfall-induced landslides fundamentally arises from the coupling of moisture transport efficiency and geotechnical strength degradation within specific geomorphic units (Wicki et al., 2020; Yu et al., 2021). Spatially, such landslides are concentrated in high-rainfall zones and permeable lithologies, where hydro-mechanical feedback dominates slope destabilization. High-rainfall zones, characterized by frequent and intense precipitation, impose dual hydrological stresses on slopes: surface runoff erodes toe regions, while infiltration elevates pore pressures, collectively acting as external drivers of failure. Highly permeable strata, characterized by high porosity or interconnected fractures, accelerate water migration. Combined with high permeability, these properties regulate water retention time within the slope and control the efficiency of pressure transmission, forming an internal transport network that facilitates landslide progression. The superposition of these mechanisms drives slope stability beyond critical thresholds over short timescales, culminating in abrupt failure.

What determines the critical threshold for rainfall-induced landslides? First, it is essential to define the critical threshold as the minimum amount of rainfall required to trigger a landslide under specific geological and topographic conditions (Naidu et al., 2018; Segoni et al., 2018b). This threshold is typically classified into two types: empirical thresholds, which are derived from statistical relationships between historical landslide events and rainfall data, and physically based thresholds, which incorporate hydromechanical models. Both approaches assume rainfall as the primary destabilizing driver. To operationalize these thresholds for landslide prediction, monitoring systems integrate rain gauge and remote sensing to assess proximity to critical saturation levels (Li et al., 2023a; Piciullo et al., 2018). Moreover, the relationship between rainfall and landslides is often nonlinear and influenced by multiple factors. Deep learning models enable data-driven determination of context-specific critical rainfall values across diverse geological and topographical settings (Sala et al., 2021; Segoni et al., 2018a). For example, Badakhshan et al. (2025) incorporated the role of soil strength. Soares et al. (2022) utilized the U-Net model, reveals that the inclusion of a normalized vegetation index layer enhances model balance and significantly improves segmentation accuracy.