the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Always on my mind: indications of post-traumatic stress disorder among those affected by the 2021 flood event in the Ahr valley, Germany

Marie-Luise Zenker

Philip Bubeck

Annegret H. Thieken

The devastating floods that swept through the Ahr valley in July 2021 left indelible marks on the region's landscape and communities. Beyond the visible damage, experience from other events suggests an increase in mental health issues among those affected. However, there is a lack of data and understanding regarding the impact of flooding on mental health in Germany. Therefore, this study aims to determine how much the flooding in 2021 affected the population's mental wellbeing. For this purpose, a household-level survey (n=516) was conducted in the district of Ahrweiler, Rhineland-Palatinate – Germany's most-affected region – 1 year after the flood event, specifically in June and July 2022. The survey employed a short epidemiological screening scale to assess the prevalence of individuals showing indications of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Using binary logistic regression analyses, we identify risk and protective factors that may have played a role in the development of PTSD to find intervention points for supporting those affected. Our findings indicate significant mental health issues 1 year after the flood event, with 28.2 % of respondents showing indications of PTSD. Furthermore, this study has uncovered essential risk factors for developing indications of PTSD after flooding: female gender, being seriously injured or becoming sick during the event, and feeling left alone to cope with flood impacts. The study emphasizes that severe flooding, such as the 2021 flood, results in new health-related needs that demand attention. As a result, care methods should be adapted to tackle the prevalence and risk factors connected with PTSD in the affected population, e.g., by providing targeted aftercare for individuals who were injured or became sick during the flood event.

- Article

(2876 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

Floods are the most prevalent type of natural hazards globally. They were accountable for the suffering of 1.65 billion people, 104 614 fatalities, and economic losses of USD 651 billion from 2001 to 2019 (CRED and UNDRR, 2020). As the number of people living in flood-prone areas and the value of their assets continue to increase, these numbers are expected to rise in the future (Kron et al., 2019; Jongman et al., 2012). Further, due to climate change, extreme precipitation is expected to increase (Seneviratne et al., 2021), leading to an even higher risk of flooding (Tradowsky et al., 2023; Alfieri et al., 2015; Jongman et al., 2014).

Floods can cause significant damage to property, belongings, and critical infrastructure and can disrupt essential services. These events can also result in injuries, infections, and loss of life. Moreover, they can have a lasting impact on the mental health and wellbeing of those affected (e.g., Thieken et al., 2023a, 2016; Tapsell, 2010). Tapsell (2010, p. 407) has stated that “the majority of their problems are just beginning, and people have to cope with the significant aftermath of the flood, not only at a practical level but also socially and psychologically”.

The extent of flood impacts became evident again in July 2021 when severe floods hit western European countries (Tradowsky et al., 2023). In Germany, the federal states of Rhineland-Palatinate, North Rhine-Westphalia, Bavaria, and Saxony were impacted, with overall damage of EUR 33 billion and around 190 flood fatalities. The Ahr valley in Rhineland-Palatinate was the most affected area, with 135 flood-related fatalities and one missing person (Thieken et al., 2023a). Many people lost their homes and loved ones, suffered injuries, or were still preoccupied with rebuilding and financial recovery 1 year after the event. Experiencing such traumatic events can have a long-lasting impact on a person's mental health.

Various studies have explored the effects of flooding on individuals' wellbeing and quality of life. Others have shown a considerable rise in the number of individuals suffering from mental disorders in the aftermath of flood disasters. These disorders may include post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, or anxiety. Among these, PTSD has been the most extensively researched (Galea et al., 2005; Stanke et al., 2012; Fernández et al., 2015; Golitaleb et al., 2022; Keya et al., 2023). PTSD is the most common mental disorder that can develop after a traumatic event (Dreßing and Foerster, 2021). It can occur due to a person's exposure to a potentially traumatic event, which is characterized by the following two conditions: first, the person experienced or witnessed an event that posed a severe threat of death or serious injury for him or herself or for another person. Second, the reaction to that event included intense fear, helplessness, or horror (American Psychiatric Association, 1994).

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses have revealed a broad range in the prevalence of PTSD in the aftermath of disasters. Recent studies conducted by Keya et al. (2023) and Golitaleb et al. (2022) have found that the prevalence of PTSD ranges from 2.6 % to 52 % and from 18.6 % to 40.3 % (mean 29.4 %), respectively, with most of the studies being conducted in Asia. However, there is also literature available on PTSD after flooding in Europe, with the majority of publications originating from the UK, showing PTSD prevalence from 6.6 % to 27.9 % (Graham et al., 2019; Jermacane et al., 2018; Paranjothy et al., 2011; Mason et al., 2010; Tunstall et al., 2006). Further, a study from France focused on how personality traits and cognitive emotional regulation strategies interact with PTSD after people experience a flood (Puechlong et al., 2020). Limited research has been conducted in Germany. After the flooding event in 2002, there was a study about mental health in patients who had to be evacuated from a heart disease center in Dresden (Nitschke et al., 2006). Another study was conducted after the flooding event of 2013, showing PTSD prevalence of 20.4 % 1 year post-event. They named difficulties or the absence of support (financial as well as psychosocial interventions) in the aftermath of disasters as predictors for negative mental health (Apel and Coenen, 2021). However, these particular flood events in 2002 and 2013 were mainly slow-rising fluvial floods, with return periods of less than 300 and 500 years at the Mulde River (Kreibich et al., 2005; Merz et al., 2014). These floods were less severe compared to the fast-onset floods of 2021, where the discharge of the Ahr River at the Altenahr gauge far exceeded the 1000-year return period (Vorogushyn et al., 2022). However, some regions in the Eastern Ore Mountains experienced similar dynamics during the 2002 floods.

In addition to examining the number of people showing indications of PTSD after a flood event, many studies have assessed factors that might affect the onset of mental health problems. Socio-demographic factors have been studied extensively, indicating that women are at a higher risk of developing such issues than men (Paranjothy et al., 2011; Mason et al., 2010; Tunstall et al., 2006; Norris et al., 2002). Additionally, the economic situation of a person or household was found to be important, as households with low income seem to be more susceptible to suffering from mental health issues (Graham et al., 2019; Lamond et al., 2015; Paranjothy et al., 2011; Mason et al., 2010; Tapsell, 2010; Galea et al., 2007; Tunstall et al., 2006). Other personal factors can also play a role, such as personal traits (Puechlong et al., 2020) or the health status before the event (Paranjothy et al., 2011; Mason et al., 2010; Tunstall et al., 2006). By contrast, there are inconsistent findings for age (Norris et al., 2002; Galea et al., 2007; Stanke et al., 2012; Fernández et al., 2015; Graham et al., 2019). Further, it is important to take into account the characteristics of a flood event, such as the depth of water or the flow velocity (Tunstall et al., 2006; Paranjothy et al., 2011; Lamond et al., 2015; Bubeck and Thieken, 2018). In addition, the circumstances and stress experienced during a flood event as a result of these flood characteristics can affect whether a person exhibits signs of mental health issues, for example, whether they were injured or required rescue (Galea et al., 2007; Wiseman et al., 2013).

Moreover, the period following a traumatic event can be strongly linked to negative mental health. According to Tunstall et al. (2006), this impairment to health can result from the reconstruction process, caused by several factors such as a disruption of the daily routine, lack of or insufficient insurance coverage, and the unavailability of skilled labor. The most commonly reported cause related to the rebuilding process is significant financial loss (Galea et al., 2007; Paranjothy et al., 2011; Jermacane et al., 2018; Bubeck and Thieken, 2018). Other factors that may contribute to the development of PTSD include displacement (Paranjothy et al., 2011; Galea et al., 2007; Tunstall et al., 2006; Nitschke et al., 2006) or disruption to essential services (Bei et al., 2013; Paranjothy et al., 2011; Tunstall et al., 2006). Also, different coping mechanisms influence mental health (Bubeck and Thieken, 2018; Lamond et al., 2015; Mason et al., 2010). While a considerable amount of relevant literature already exists, relationships between these factors are complex. Studies do not always agree on the significance of influencing factors or on the direction of influence (Lamond et al., 2015).

Altogether, there is already a body of relevant literature on the impacts of flooding on mental health. However, relationships between these factors are complex and have not been fully investigated or understood yet; for instance, there is still limited knowledge about the reconstruction time and lasting psychosocial effects and recovery processes following flooding. In particular, there is little research on the mental health impacts of flooding in Germany, which makes it difficult to understand how much the flooding of 2021 affected the population.

Although flooding represents a significant natural hazard in Germany (Munich Re, 2018), the region lacks a comprehensive framework to address the social and psychological impacts of disasters, which other countries have already established. For example, the USA recently launched the Post-Disaster Mental Health Response Act (US Government, 2022), Australia has the Australian National Disaster Mental Health and Wellbeing Framework (National Mental Health Commission, 2023), and England had already established its guidelines on dealing with psychosocial and mental health after disasters in 2009 (DH Emergency Preparedness Division, 2009). Such a framework could help address the mental health needs of those affected by flooding. This lack of attention from policymakers and a noticeable gap in (fundamental) research can lead to insufficient support for individuals struggling with mental health issues. Additionally, such situations can create new demands that require immediate attention. However, we cannot identify the additional support needs without further research.

To address this gap, we conducted a household-level survey 1 year after the flood event in the Ahrweiler district, Germany's most-affected region. The survey used a short screening scale to determine the prevalence of PTSD and binary regression analyses to identify factors that influenced the indications of suffering from PTSD. Our aim was 2 fold: to determine the share of people in the heavily affected Ahrweiler district who exhibited signs of PTSD following the flood and to identify any risk or protective factors that may have played a role in the development of their PTSD. The study is crucial because it reflects the outstanding severity of the flood event in Europe, which lets us assume that a significant portion of the population experienced conditions that match those of PTSD. The study provides information on how much support needs to be provided in the aftermath of severe floods to help make societies more flood resilient. Further, with our study, we aim to contribute to developing guidelines for Germany on handling flood impacts on mental health.

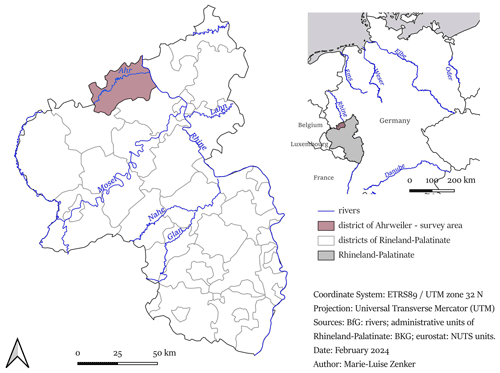

2.1 Case study

Persistent and regionally very pronounced rainfall over western Europe from 12 to 19 July 2021 led to catastrophic flood events, particularly in the steep Ahr valley in Rhineland-Palatinate (Tradowsky et al., 2023; Junghänel et al., 2021). According to the German Weather Service (Junghänel et al., 2021), local rainfall maxima exceeded 150 mm in 24 h in some locations, resulting in quickly rising flash floods that caused unparalleled human and economic losses in Germany (Thieken et al., 2023a, b; Dietze et al., 2022). In the Ahr valley alone, 135 lives were lost and one person is still missing (Thieken et al., 2023a). For the whole of Germany, around 190 people were reported dead (Thieken et al., 2023a). The only flooding in Germany that exceeded this number was the storm surge in 1962 along the North Sea coast (Paprotny et al., 2018; Thieken et al., 2023b). One possible reason for the high death toll was that the flood forecasting, warning, and response system (FFWRS) failed in areas affected by quickly rising flash floods, particularly in the Ahr valley, catching many people by surprise during the night (Thieken et al., 2023b; Fekete and Sandholz, 2021). At least 770 people were injured and several had to be dramatically rescued or were reported missing for several days (Kron et al., 2022). Also, economic losses were unprecedented, amounting to as much as EUR 33 billion for Germany (Munich Re, 2022). This number by far exceeds direct economic losses reported for previous large-scale river floods along the Elbe and Danube in 2002 and 2013 (Kron et al., 2022). In the Ahr valley, critical infrastructure, such as railway tracks and bridges, was heavily impacted. A total of 103 bridges along the Ahr River were destroyed and will need to be reconstructed in the coming years. Deutsche Bahn (2022) reported that restoring train infrastructure and services will take years.

2.2 Sampling

To understand the impact of such an extreme flood event on mental health, we surveyed residents in the heavily affected district of Ahrweiler in Rhineland-Palatinate. Affected households were sampled from the residents who had applied for emergency financial relief (Soforthilfe). The federal state of Rhineland-Palatinate initiated this financial relief program to cover residents' urgent necessities in the flood's direct aftermath. Affected households from the district of Ahrweiler could apply for emergency relief until the 10 September 2021. In total, more than 17 000 applications were submitted. Around 12 300 applications for immediate relief were granted and more than EUR 25 million was distributed (Statistical Office RP, 2021). The main reasons for denying applications were duplicate applications from the same household and incorrectly filed applications from companies and applicants who did not have their principal residences in the district of Ahrweiler. The financial relief was distributed by Ahrweiler's district authorities (Statistical Office RP, 2021).

With the support of the district administration, every third household that had applied for financial emergency relief was randomly selected and invited to participate in an online survey between June and August 2022, specifically 5250 households in total. They were contacted in the form of a letter signed by the district administrator. To ensure that we also included respondents without internet access and those who did not want to complete the questionnaire online, residents could also request a printed version. Twenty-one people completed the paper version of the questionnaire. About 40 letters did not reach the addressees because they could not be delivered. In total, 516 residents completed the questionnaire, equaling a response rate of 9.9 %. For further details on the sampling procedure and the total sample, see Truedinger et al. (2023).

Altogether, the questionnaire contained 76 questions addressing the following topics: mental health status – especially screening for PTSD – recovery and reconstruction; social vulnerability; and opinions about flood risk management.

Out of 516 completed questionnaires, only 411 could be used for screening PTSD due to missing values for the symptom questions. Since these questions are essential for calculating the indications of PTSD, the remaining 105 questionnaires had to be excluded from further analyses. Of the 411 respondents, 54.5 % were male, 44.8 % female, and 0.7 % did not answer. This indicates a slight gender bias in the sample population, as Ahrweiler's overall population was evenly split between women (50.6 %) and men (49.4 %) in 2022 (Statistical Office RP, 2024). The sample is mainly representative with respect to age (when removing people under 18 from official statistics). It includes participants ranging from their twenties to over 80 years old. The majority of people belonged to the age group of 50–59 years old, a group which was also the majority in Ahrweiler (Statistical Office RP, 2022). The median net monthly household income in the sample was EUR 2600–3599. Official statistics reported a yearly disposable household net income of EUR 24 590 per resident in the district of Ahrweiler in 2020 (Statistical Office RLP, 2023). While the numbers are not directly comparable, the income range appears plausible.

This survey was approved by the ethical committee of the University of Stuttgart in July 2022 (see Truedinger et al., 2023).

2.3 Measurement and methods

2.3.1 Screening PTSD after the flooding event

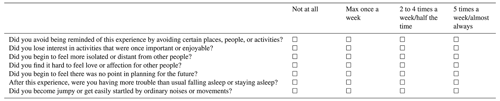

To detect indications of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among affected residents, we used the German short epidemiological screening scale by Siegrist and Maercker (2010). It is based on the scale developed by Breslau et al. (1999), which is closely in line with the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV; Siegrist and Maercker, 2010; Breslau et al., 1999; American Psychiatric Association, 1994).

Symptomatology of PTSD includes trauma re-experience, emotional numbing or avoidance, and hyper-arousal (American Psychiatric Association, 1994; Frans et al., 2005). The screening tool employed in this study comprises seven items, five of which relate to symptoms of avoidance and numbing and two to the hyper-arousal group (Siegrist and Maercker, 2010; Breslau et al., 1999). The short version of the screening tool was empirically derived from 17 items (symptoms) for PTSD according to the DSM-IV, which best identified respondents with PTSD in a telephone survey in the USA (Breslau et al., 1999). Good sensitivity, specificity, test–retest reliability, and internal consistency of the short screening scale have been demonstrated by various studies (Siegrist and Maercker, 2010; Breslau et al., 1999; Kimerling et al., 2006). Validation of the English version of the short screening tool revealed high agreement with the extended US version (Breslau et al., 1999).

Kimerling et al. (2006) evaluated Breslau's seven-item scale by comparing the self-administered results of 134 participants with the results from clinical interviews of the same patients carried out by psychologists using the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS). They concluded that the short screening scale was suitable for detecting probable PTSD prevalence without a lengthy or specific trauma assessment (Kimerling et al., 2006), which is the goal of this study.

The screening tool assesses how often the seven symptoms have occurred in the last 4 weeks, with a 4-point answering scale ranging from “not at all” to “5 times per week/almost always”. A complete version of the seven-item scale is provided in Table A1 in Supplement A. A respondent is considered to be showing the symptom if the respondent indicates the highest or second-highest option (i.e., “2–4 times a week/half of the time” or “5 times per week/almost always”). The PTSD score ranging from 0 to 7 is calculated by summing up the outcomes of all seven items (symptoms). An indication of PTSD then exists if the respondent reports four or more symptoms. The cutoff point of four is derived from empirical studies and is commonly applied, as it has been proven to discriminate between patients with and without PTSD best (Siegrist and Maercker, 2010; Kimerling et al., 2006; Breslau et al., 1999). Breslau et al. (1999, p. 908) reported that a score of 4 or greater “defined positive cases of PTSD with a sensitivity of 80 %, specificity of 97 %, positive predictive value of 71 %, and negative predictive value of 98 %.”

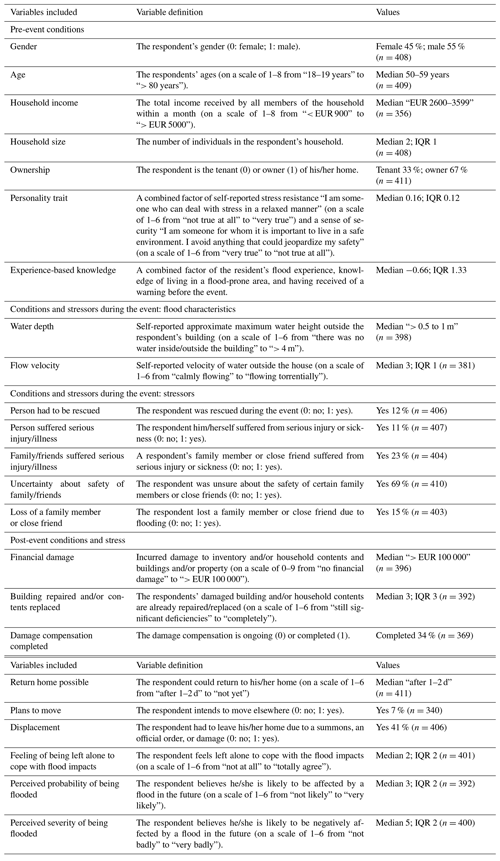

As stated in Sect. 1, there is a variety of research on factors influencing PTSD. For this study, we used an exploratory approach, which allowed us to identify stressors specific to the Ahr valley region to gain a more nuanced understanding of the region's vulnerability and mental health status. Potential stressors were related to the conditions for probable PTSD according to the DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) and empirical findings from other studies exploring the impact of PTSD following flood events (e.g., Galea et al., 2007; Lamond et al., 2015).

We grouped the potential influencing factors into four categories: (a) pre-existing conditions, (b) flood characteristics, (c) stressors during the event, and (d) post-event conditions and stress. The first category refers to conditions that describe a person or community before the flooding event, such as socio-demographic factors. In our study, gender, age, household income, size, and ownership were used. Further, personality traits and experiential knowledge describe a person or household before this event happened. The second category includes water level and flow velocity to describe the magnitude of the flood event. The third category is still considered a description of the conditions during the flooding event and was induced by the flood characteristics. These encompass whether respondents had to be rescued, if they were uncertain about the safety of loved ones or lost someone due to the flooding event, or if they or their relatives became injured or sick due to the flood. The fourth category includes variables defining stress and coping mechanisms after the event. This involves the incurred asset damage and its repair or replacement, e.g., replacing the damaged building or contents or obtaining damage compensation within a year of the event. The amount of financial loss is also taken into account. Due to the event, many individuals had to leave their homes and have not yet been able to return. Some plan to relocate. Their personal feelings and perceptions are also considered part of this category. For a comprehensive list of all variables used, please refer to Table 1.

2.3.2 Statistical analyses

IBM SPSS Statistics version 29.0 was used for data preparation and analysis. Descriptive analyses were performed to gain an overview of the data, and correlation analyses were performed to test for multicollinearity and coherence of different variables.

As stated in Sect. 2.3.1, the questionnaire contained various questions. Overall, 26 questions that could influence the development of PTSD were taken into account. To simplify this vast number of variables, a principal component analysis (PCA) was performed to reduce the enormous number of potentially important variables from the dataset, reduce dimensions (Norris and Lecavalier, 2010), and avoid multicollinearity. Therefore, oblique (specifically oblimin) rotation was used since this is recommended for only partially independent variables in social and behavioral research (Norris and Lecavalier, 2010). This approach condensed two variables representing personality traits into a singular factor. Additionally, three variables were consolidated into experiential knowledge, which encapsulates participants' understanding and experience of floods and warnings (Table 1). Following this approach, a total of 23 predictors were available for analysis.

Further, the existence of a PTSD indication (yes/no) was subsequently used in a logistic regression analysis to understand the influence of various potential stressors and protective factors. These stressors were explored empirically through exploratory research. We developed separate binary logistic regression models for each of the four categories, considering the binary indication for PTSD or non-PTSD cases as the dependent variable. Subsequently, an overall model was conducted incorporating variables from each of the four models that proved significant at a 10 % significance level.

Additionally, two predictor variables underwent a sensitivity analysis, namely whether a respondent was injured or got sick and the respondent's perceived severity of negative effects on the future. One reason for testing the explanatory power of getting injured or sick was the uncertainty in causality. Some respondents may have been diagnosed with a mental health disorder due to the flood event before the survey but that was not what the particular question was trying to assess. This question aimed to determine whether the respondents had experienced infections, injuries, distress, etc. The second sensitivity analysis was undertaken because the perceived severity of negative effects on the future matched the definition of PTSD and could also be classified as a symptom (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). The two predictors were removed from their categories and from the overall model. Nagelkerke's R2 and the Akaike information criterion (AIC) determined whether the predictors strongly affected the models or could be neglected.

Experiencing such a dramatic flood event represents an enormous mental burden for those affected. At the time of the survey, i.e., around 1 year after the event, about 42 % of the respondents reported that they still felt (very) strongly burdened by the event.

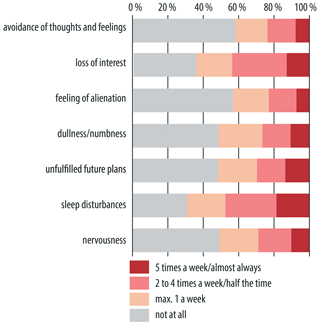

3.1 Distribution of PTSD symptoms

Figure 2 illustrates the frequency of symptoms based on the short screening scale. Our findings indicate that 67.9 % of respondents experienced at least one (out of seven) PTSD symptom 1 year post-event. Indeed, 5.1 % experienced all seven symptoms. Figure 2 displays the symptoms recognized as indicative of developing PTSD (see Sect. 2.3.1). Nearly half of the respondents experienced symptoms at least once a week, with even higher percentages reporting sleep disturbances and loss of interest in activities. About 70 % of the participants reported problems sleeping at least once a week and 20 % experienced them almost daily. Additionally, many participants reported no longer enjoying activities that they used to enjoy before the flooding. The least commonly reported symptom was avoidance of thoughts, feelings, and places that reminded them of the event (Fig. 2).

Figure 2Distribution of PTSD symptoms reported about 1 year after the occurrence of the flooding event, using the PTSD screening scale by Siegrist and Maercker (2010). n=411 for each bar.

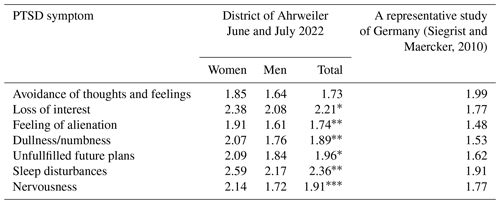

Our study found significantly higher indications of PTSD in six out of seven symptoms than were found in a 2005 epidemiological study representative of Germany's total population using the same PTSD screening tool (Table 2). While sleep problems and loss of interest were also the most common symptoms reported 1 year after the flooding event, the avoidance of thoughts, feelings, and people associated with flooding was less frequent in our study.

Table 2Mean values of the PTSD symptoms with possible answers ranging from 1 (not at all) to 4 (5 times a week/almost always) compared to a representative study of the total German population from 2010 measuring PTSD with the same screening tool (Siegrist and Maercker, 2010). The Pearson chi-squared test indicates gender differences with p values of < 0.05*, < 0.01, and < 0.001.

When comparing symptoms between genders in our study (Table 2), six out of seven symptoms were significantly higher for women. The only symptom that did not show statistically significant differences was the avoidance of thoughts, feelings, and people associated with the flooding. We assume that the ongoing reconstruction work, dealing with financial issues and insurance, and visible damage to buildings and infrastructure made it impossible to ignore the enormous impacts of the event, which were still visible at the time of the survey. Additionally, the flooding event still receives attention in national and local media, and ongoing research continuously strives to understand the circumstances better to help those affected.

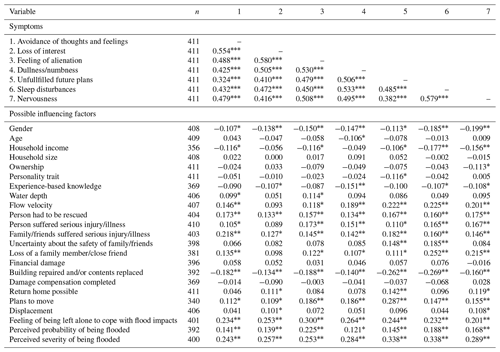

The correlation analysis between all seven PTSD symptoms shows a significant correlation between each symptom at a 10 % level (Table 3). Strong co-morbidity can be seen for loss of interest and feelings of alienation (r= 0.58; p<0.01), loss of interest and avoidance (r= 0.54; p<0.01), and sleep disturbances and nervousness (r= 0.58). These co-morbidity levels suggest that selecting a single outcome variable in regression modeling is practical, given the likelihood that similar factors will influence all outcomes, thereby reducing co-linearity. Moreover, the co-morbidity suggests that individuals encountering one symptom are more likely to experience multiple ones. This is supported by Lamond et al. (2015), who tested the co-morbidity of different psychosocial symptoms after a flood in 2007 in the UK. Moreover, several studies suggest substantial co-morbidity of psychiatric disorders (Galatzer-Levy et al., 2013; Brady et al., 2000). Depression, anxiety disorders, and substance use in particular are known to share symptoms with PTSD (Galatzer-Levy et al., 2013; Brady et al., 2000). In our study, we found an overlap with depression symptoms regarding sleep disturbances, avoidance, and loss of interest in activities, whereas anxiety, avoidance, and increased arousal overlap with PTSD symptoms. This highlights the complexity of mental health disorders and their coexistence, implying further that individuals who exhibit intense symptoms of PTSD may experience additional mental health impacts in addition to those related to PTSD. Altogether, the high co-morbidity levels indicate that the flooding interrupted the affected individuals' daily routines.

Table 3Correlation analysis of symptoms of PTSD with one another and with the potentially influencing factors for PTSD used in this study. The Pearson correlation coefficient and two-sided significance test indicating p values of < 0.05*, < 0.01, and < 0.001 are given.

Table 3 shows a further correlation analysis between the seven PTSD symptoms and all the predictor variables used in this study, showing significant relationships between feeling alienated and feeling left alone to cope with the flood impacts (r= 0.30; p<0.01), as well as between sleep disturbance and perceived severity of adverse effects of the flood in the future (r= 0.34; p<0.01). Experiencing such a traumatic event is linked to the fear of recurrence and of being strongly affected in the future. This fear is strongly associated with adverse mental health, as was also discovered by Puechlong et al. (2020) and Mason et al. (2010). Catastrophizing, a non-adaptive cognitive emotional regulation strategy, is also a risk factor for PTSD that is connected to the abovementioned factors (Puechlong et al., 2020).

3.2 Prevalence of flood-related PTSD

A total of 71.8 % of respondents did not exhibit indications of PTSD, according to the epidemiological screening tool. However, with a prevalence of 28.2 %, it is evident that a significant portion of respondents displayed indications of PTSD approximately 1 year after the flooding event. The prevalence was significantly higher for women (36 %, 184 female participants) than for men (22 %, 224 male participants; p<0.01).

The estimated prevalence of PTSD was substantially higher than is typically found in the total German population. An epidemiological study conducted in 2016 (Maercker et al., 2018) found a 1-month prevalence of 1.5 %. In contrast, the Robert Koch Institute reported a 12-month prevalence of 2.3 % for PTSD in Germany, with women being more affected (3.6 %) than men (0.9 %; Jacobi et al., 2014). Another study of six European countries showed even smaller prevalence rates in the population (0.9 %; Alonso et al., 2004).

However, when comparing the estimated prevalence to the literature in which PTSD was examined after flooding events, findings are very heterogeneous, ranging from 2.6 % to 52 % after flooding (Golitaleb et al., 2022; Keya et al., 2023). It is important to note that most of these studies were conducted in Asia, where circumstances, susceptibilities, and methods of handling floods may differ from those in Europe. This could affect the outcomes of the studies. Nevertheless, our results fit the average of 29 % given by Golitaleb et al. (2022) and seem comparable to the other findings.

It is also essential to account for the time elapsed after a traumatic event when considering the prevalence of PTSD. The percentage of people experiencing mental health symptoms can vary considerably after 6 months compared to those who have experienced a flood 1, 2, or more than 2 years ago (Mason et al., 2010; Jermacane et al., 2018; Graham et al., 2019; Zhong et al., 2018). Moreover, the overall severity of the event can contribute to differences in prevalence (Laudan et al., 2020). For Germany, the study of Apel and Coenen (2021) discovered 20.4 % PTSD prevalence a full 12 months after the flood of June 2013. However, as stated in Sect. 1, this flooding differed in type and severity compared to this case study.

In addition to possible differences in regions and cultures, it could be that the method of assessing PTSD can contribute to the variations in prevalence, for example, when diagnostic criteria are updated (e.g., DSM-III to DSM-IV to DSM-V; Schwarz and Kowalski, 1991; Wang et al., 2000; Galea et al., 2005).

It is important to note that we were unable to filter out individuals who may have already been experiencing symptoms of PTSD before the flooding since we did not gather information on their pre-flood mental health status. However, information on respondents' pre-existing health status before the disaster can be crucial in determining the exact impacts of the flooding event because physical impairments and chronic health conditions are known to influence mental health problems (Galea et al., 2005; Tunstall et al., 2006). Additionally, the still-ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine may have also had an impact on the prevalence of PTSD. Further, self-selection bias is possible, since those affected and randomly selected were able to voluntarily participate in the survey. Since individuals with severe mental health issues may have chosen not to complete the survey, this could have resulted in an underestimation of the true prevalence of PTSD 1 year after the flooding event. However, we took steps in the survey introduction to inform participants about the possibility of re-traumatization. We also recommended that only those who felt comfortable participate in the survey.

3.3 Factors influencing the development of PTSD

The flood caused significant damage to many of the households that were surveyed. Half of the households suffered financial losses of more than EUR 100 000. The water entered the cellar of every household, while 47.2 % had water on the outside of their homes up to 2 m or even higher (40.1 %). Over 40 % of respondents had to vacate their homes due to the damage and 14.4 % were still unable to return home at the time of the survey, i.e., 1 year after the event. Additionally, 90 % of respondents reported that the damaged buildings or contents had not been fully repaired or replaced. All of these conditions and stressors and more could influence the mental health status of those affected. The regression analyses presented in what follows reveal the relationship between potential factors and PTSD.

3.3.1 Pre-existing conditions

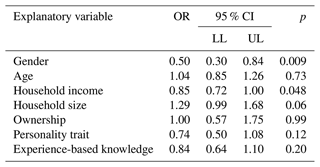

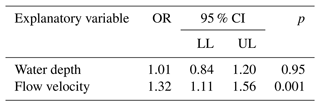

In this model, seven variables were tested, explaining 8 % of the variance (Nagelkerke's R2= 0.08). As can be seen in Table 4, gender is a significant pre-existing demographic predictor of PTSD with an odds ratio (OR) of 0.4 (95 % CI 0.2–0.8; p<0.01), showing that men are less likely to show indications of PTSD while women are more susceptible to developing PTSD. This is consistent with previous research, which has often shown gender to be a factor in the development of mental health issues (e.g., Paranjothy et al., 2011; Mason et al., 2010; Tunstall et al., 2006; Norris et al., 2002). However, this can have different explanations, often depending on social norms. On the one hand, women tend to be more sensitive and can express and show feelings more easily (Tunstall et al., 2006). They typically take on the primary care giver role and are generally more concerned about their community (Pulcino et al., 2003; Tunstall et al., 2006). On the other hand, men are often associated with the stereotype of being strong and not showing or talking about their vulnerabilities (Seidler et al., 2019).

Table 4Results of the binary regression analysis for pre-existing conditions, considering the binary indication for PTSD or non-PTSD cases.

n=320, Nagelkerke's R2=0.08, AIC = 379.40. CI = confidence interval, LL = lower limit of the confidence interval, UL = upper limit of the confidence interval.

Household income and household size have a significant correlation with disaster-related PTSD as per the model (OR 0.8, 95 % CI 0.7–1.0; OR 1.3, 95 % CI 1.0–1.7). This indicates that households with lower incomes are more likely to experience adverse mental health outcomes in the aftermath of disasters. The literature also suggests that income is a crucial factor associated with negative mental health effects after disasters (Graham et al., 2019; Lamond et al., 2015; Paranjothy et al., 2011; Mason et al., 2010; Tunstall et al., 2006; Galea et al., 2005). On the other hand, high income can be seen as a protective factor. However, age, ownership, personality, and experience-based knowledge had no significant effects (Table 4) on this model.

3.3.2 Conditions and stressors during the event

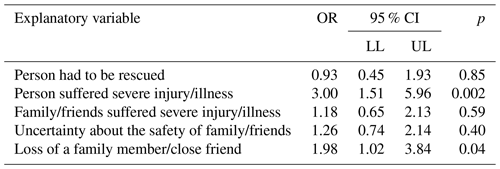

The flood characteristics define the initial shock and the event's magnitude and play a crucial role in determining the impact. There are several known parameters (Thieken et al., 2005); however, only water depth and flow velocity were recorded in this study and 5 % of the variance in the data was explained (Table 5).

The results for flow velocity in this model show a significant effect on the development of indications for PTSD (OR 1.3, 95 % CI 1.1–1.6; p= 0.001). This is in line with Bubeck and Thieken (2018), where flood velocity significantly predicted negative recovery for the (fluvial) flood of 2013 in Germany. However, water depth does not impact PTSD in our study, which is contradictory to other findings (Lamond et al., 2015; Lowe et al., 2013; Paranjothy et al., 2011).

The event's severity is also reflected in respondents' personal experiences during the flood. Five stressors proposed by Galea et al. (2007) were tested within this model (see also Table 1). Altogether, these predictors explain 8 % of the variance in the data.

At 75.9 %, the vast majority of respondents reported experiencing at least one of the five stressors (see “Conditions and stressors during the event: stressor items” in Table 1; mean 1.3, SD 1.1, n= 390), with uncertainty about the safety of a family member or close friend being the most prevalent at 69 %. Nevertheless, this particular variable does not serve as a predictor for PTSD as its prevalence is comparable among residents who both do and do not exhibit indications of PTSD (see Table 6). In contrast, respondents who suffered from a severe injury or got sick due to the flooding show a high OR of 3.0 (95 % CI 1.5–6.0; p<0.01), meaning that if those affected were physically traumatized during the event, the likelihood of experiencing PTSD increased by 200 %. Further, the sensitivity analysis reveals that this predictor contributes significantly to the model's performance, with R2= 0.08 and AIC = 447.39 (see Table 6); without the injury/illness predictor, the values were R2= 0.06 and AIC = 458.29 (see Table B1). Assuming the respondents related the question to the event seems reasonable since the questions before and after also referred to it. However, we cannot completely rule out the question having been misunderstood so that the illness referred to in the answers was a mental health disorder triggered by the flood event and was diagnosed prior to the survey. Therefore, we have decided to keep it in the model and investigate this question more thoroughly in the future. Nevertheless, becoming seriously injured during a flooding event is solid, tangible evidence that a person can feel and see and matches the definition of PTSD according to the DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). According to Wiseman et al. (2013), PTSD is the most common disorder that people experience after a traumatic event, especially if they have been physically injured, regardless of the severity of the injury. Similar results were found by Galea et al. (2007). Although Bromet et al. (2017) found a significant effect in their univariate model, it was not present in their multivariate models.

Further, the loss of a family member or close friend emerges as a significant PTSD predictor for residents (OR 2.0, 95 % CI 1.0–3.8; p<0.05) in this model. This finding is consistent with the literature (Keyes et al., 2014; Atwoli et al., 2017; Bromet et al., 2017). No influence was detected on the stressors requiring rescue or a family member's serious illness or injury.

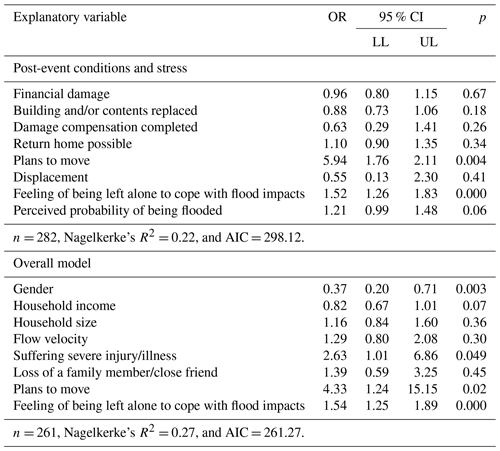

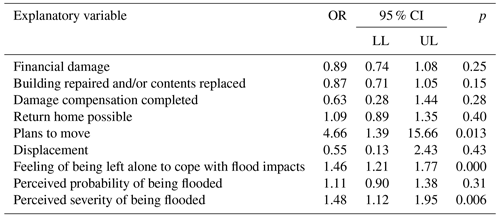

3.3.3 Post-event conditions and stress

In summary, the fourth model deals with variables that occur after the initial shock of a flood event has subsided and the reconstruction and recovery process begins. The model is represented by eight variables and explains 26 % of the variation in the data, making it the most meaningful so far. This underlines the importance of recovery processes for the wellbeing and health of disaster-affected regions.

Table 5Results of the binary regression analysis for flood characteristics during the event, considering the binary indication for PTSD or non-PTSD cases.

Note: n= 381, Nagelkerke's R2= 0.05, AIC = 455.33, CI means confidence interval, LL is the lower limit, and UL is the upper limit.

Table 6Results of the binary regression analysis for stressors based on Galea et al. (2007) during the event, considering the binary indication for PTSD or non-PTSD cases.

Note: n= 390, Nagelkerke's R2= 0.08, AIC = 447.39, CI means confidence interval, LL is the lower limit, and UL is the upper limit.

One year after the event, 38.3 % of respondents displaying indications of PTSD expressed feelings of being left alone to cope with flood impacts compared to 18.2 % of residents without indications of PTSD. Table 7 shows an OR of 1.5 (95 % CI 1.2–1.8; p<0.000), implying that respondents who feel left alone to cope with flood impacts are 50 % more likely to show indications of PTSD. There is limited evidence in the literature regarding this factor. Nonetheless, most studies suggest that having a support system of friends and neighbors can be helpful in protecting against mental health issues during the coping process (Norris et al., 2002; Tunstall et al., 2006; Stanke et al., 2012).

Table 7Results of the binary regression analysis for post-conditions and stress, considering the binary indication for PTSD or non-PTSD cases.

Note: n= 278, Nagelkerke's R2= 0.26, AIC = 290.48, CI means confidence interval, LL is the lower limit, and UL is the upper limit.

As shown in Table 7, the perceived probability of being negatively affected by future flooding was also found to have an impact on developing indications for PTSD. To further investigate this variable, a sensitivity analysis was conducted to test whether the predictor of the perceived severity of the negative future flooding aligns with the symptoms of PTSD according to the DSM-IV. The regression analysis demonstrated that this predictor contributes to the accuracy of the model (with predictor R2 = 0.26, AIC 290.48; see Table 7. Without predictor R2= 0.27, AIC = 298.12; see Table B2), which is why we left the variable in the model.

Planning to move after the event significantly correlates with PTSD, showing the highest OR in this model at 4.7 (95 % CI 1.4–15.7; p<0.01). This suggests that PTSD could be a contributing factor leading individuals to move to a new home, making it a consequence of the disorder.

The perceived probability of experiencing the adverse effects of a possible future flood has no significant influence (OR 1.5, 95 % CI 1.1–2.0; p<0.01).

Contrary to other findings, in our study, damage does not have a significant influence on PTSD. Jermacane et al. (2018) and Galea et al. (2007) discovered that severe financial loss resulting from flooding was linked to a higher incidence of PTSD. According to Van Der Velden et al. (2023), both pre- and post-trauma financial difficulties can increase the risk of mental health problems such as PTSD. However, due to the damage scale used in this survey, the extent of financial losses was not determined precisely, leading to a small variance in the data sample.

Furthermore, there is no evidence to suggest that the lack of fully repaired or replaced damaged buildings or contents, incomplete damage compensation, no possibility of returning home, displacement, or the perceived probability of future flooding have any impact on PTSD (see Table 7).

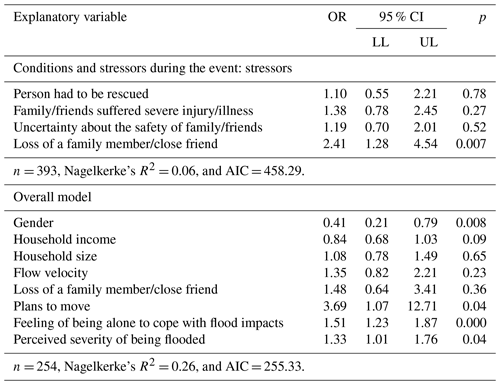

3.3.4 Overall model

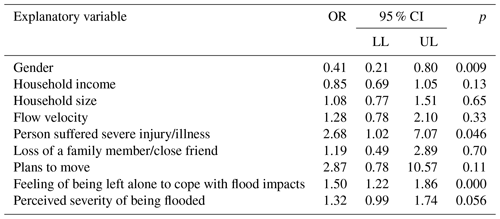

Finally, the overall model integrates predictors from all four categories presented so far, significantly above the 10 % significance level. It explains 28 % (Nagelkerke's R2= 0.28) of the variation in the data and accurately classifies 79.1 % of the categories. The model comprises nine variables, spanning all four models in Tables 4 to 7. In the overall model, three influencing factors demonstrate significant explanatory power with a p value of less than 0.05: seriously suffering from severe injury or illness, feeling left alone to cope with flood impacts, and gender (Table 8).

Table 8Results of the binary regression analysis for the final model, considering the binary indication for PTSD or non-PTSD cases.

Note: n= 253, Nagelkerke's R2= 0.28, AIC = 252.85, CI means confidence interval, LL is the lower limit, and UL is the upper limit.

During the flood event, residents who experienced an injury or got sick show a high odds ratio of 2.68 (95 % CI 1.02–7.07; p= 0.046), meaning that if those affected were physically traumatized during the event, the likelihood of developing PTSD increased by 168 %. Further, the sensitivity analysis in Table B1 reveals that this stressor needs to be considered and investigated better. As discussed in Sect. 3.2, this variable has a strong association with PTSD, according to the literature (Wiseman et al., 2013; Galea et al., 2007). This suggests that it is essential to monitor the mental health of individuals who have been injured during a flooding event and provide necessary treatment to help stabilize not only their physical but also their mental wellbeing. To exclude misinterpretations, the PTSD assessment should be accompanied by questions on illnesses and injuries induced by the flood, as well as information about the pre-disaster health status.

The odds ratio of 1.5 (95 % CI 1.22–1.86; p<0.000) suggests that individuals who feel left alone to cope with flood impacts are 50 % more likely to suffer from PTSD. Additionally, the significant positive correlation (r= 0.30; p<0.01) between feelings of alienation and the feeling of being left alone during the coping process (see Table 3) indicates a lack of support during the recovery and reconstruction phase, which is an important entry point for better post-event disaster management. Half of the survey respondents (54.4 %; n= 357) reported difficulties finding available building surveyors, craftspeople, or materials. Additionally, managing finances seems to be a source of stress for many, with 18 % (n = 357) reporting that the disbursement was insufficient or that the insurance did not acknowledge the damage and did not disburse (10.1 %, n = 357). However, a similar share stated they had enough financial reserves themselves. Moreover, 14.8 % (n = 357) had to wait for their landlord or community association to act before repairs were viable.

One attempt to support those affected by the disaster was establishing a trauma help center (Trauma Hilfe Zentrum im Ahrtal) a few months after the event happened. The center is located in one of the most affected areas and offers psychosocial counseling services. According to Katharina Scharping (personal communication, 4 March 2024), head of the center, 1475 individual counseling sessions had been held and 70 group offers were utilized as of September 2022. More than 2 years after the event, more people still seek help. We believe this center is important to support the reconstruction process and should be maintained in the long term.

According to our study, gender is the most significant demographic factor, with an OR of 0.41 (CI 95 % 0.21–0.80; p<0.01). This aligns with previous research, which indicates that women are at a higher risk, often due to societal norms (refer to Sect. 3.1).

Although the plan to move after the event shows the greatest effect size (OR 2.87; see Table 8) on PTSD among the residents, with a p value of 0.11, it does not seem to be a significantly strong predictor. This is probably due to the small sample size of respondents who plan to move (6.8 %; 28 out of n=340). The high confidence interval (CI) indicates a disagreement and ongoing discussion among the stakeholders (politicians, authorities, residents, etc.) about relocation and resettlement after the flooding event. However, the willingness to move to another location permanently is somewhat influenced by other variables, such as ownership and the housing situation at the time of the survey, and does not influence the indications of the development of PTSD. Respondents who were able to stay in their homes were less willing to move than respondents who had to move temporarily, and homeowners were less inclined to move than tenants (Truedinger et al., 2023).

Several participants in the survey raised concerns about the potential adverse effects of floods in the future. However, this was not strongly significant in the model (OR 1.32, 95 % CI 0.99–1.74; p= 0.06). The correlation analysis showed that this factor is significantly linked to sleeping disturbances (r= 0.34; p<0.01; see Table 3), the most frequently stated symptom among respondents, as well as unfulfilled future plans (r= 0.34; p<0.01). The sensitivity analysis shows R2 = 0.28 and AIC = 252.85 with the predictor, and R2 = 0.27 and AIC = 261.27 without the predictor, indicating further investigation of this variable. Mason et al. (2010) suggest that experiencing a threatening situation like a flood is linked to the fear of recurrence, which results in being strongly affected in the future. So, negatively perceiving future flood risk can harm a person's mental health, which is also supported by Puechlong et al. (2020). This feeling and the associated symptoms require proper treatment, as ignoring them may worsen the symptoms and lead to even worse mental health impacts in the future. Further, Babcicky et al. (2021) propose that such psychosocial indicators, e.g., the perceived probability and fear of being flooded again in the future, need consideration when regulating losses and supporting the recovery process rather than only looking at damages.

Although the model included the factors listed as significant in the previous sections (Sect. 3.1 to 3.3), the variables of household income and size, flow velocity, and the loss of a family member or close friend did not produce any significant results in the overall model.

The relationship between predictors and PTSD is often complex, and it is not always clear to what extent predictors are dependent on each other or even on other circumstances. This lack of clarity is also why different studies only sometimes agree on the significance of the predictors or the direction of influence. Other researchers have also addressed this issue (Galea et al., 2005; Lamond et al., 2015). Further, assessing cause and effect for potential influencing factors is difficult.

Our findings highlight the major psychosocial challenges faced by those affected during and after the flooding event. Given the severity of the flooding, we assumed that a large number of residents would experience negative mental health impacts such as PTSD. Our study provides evidence of such effects on the mental health of affected residents 1 year after the flood event in the heavily affected district of Ahrweiler. Around 70 % of those affected by the flood reported suffering from sleep disturbances and a lack of enjoyment in their activities at least once a week, which underlines the event's impact on their daily lives. Additionally, we have estimated that 28 % of respondents from the heavily affected district of Ahrweiler display indications of PTSD 1 year after the event based on the short epidemiological screening scale.

Further, by analyzing possible influencing factors that could contribute to PTSD, this study has uncovered several essential factors. Firstly, women seem to be particularly at risk of experiencing PTSD symptoms. Secondly, during the flood event itself, the most critical factor contributing to PTSD indications was whether someone became injured or sick due to the event. Thirdly, in the aftermath of the flood, the feeling of being left alone to cope with flood impacts was the most significant factor contributing to PTSD indications. Altogether, the findings show that such a catastrophic flood can lead to new health-related needs that require attention. Psychosocial offers should be adjusted to address the high prevalence of and risk factors associated with PTSD in the affected population. On the one hand, our results show that long-term support is needed. On the other hand, targeted interventions are required, especially during and after the flood event. The first implication is a targeted aftercare program for those injured during the flood event. Furthermore, the findings suggest a significant need for practical assistance during reconstruction. A helpful step was to establish a trauma support center. To ensure that those affected, who for whatever reason are unable to seek help on their own receive the help they need, it would be beneficial to introduce a visiting assistance program where qualified professionals go door to door and inquire whether they can be of any assistance (known as aufsuchende Hilfe in German). Further, results showed that difficulty in overcoming bureaucratic obstacles, in finding available building surveyors and craftspeople, and in managing finances can all hinder a speedy recovery process. Nevertheless, there is a need for further research into coping strategies. Additional research is also needed to show the causalities of different influencing factors. Additionally, more longitudinal studies are necessary, ideally with the same sample, to determine the time frame of negative mental health impacts and to obtain more insights into recovery processes. The insights can be utilized to assess the effectiveness of various measures. Finally, we propose integrating the long-term mental-health-related impacts of floods into overall flood risk management, as it is an essential part of the recovery process following a flood yet is often overlooked in many regions of the world (see Sect. 1 for selected countries with a framework). Developing a framework to support the mental health of those impacted by floods can help in building more resilient communities. Furthermore, while German flood risk management includes the term “avoidance and reduction of adverse effects on human health”, it lacks further explanation and recommendations. This study provides information to contribute to such a framework by highlighting the prevalence of and risk factors associated with PTSD following the 2021 flood in the Ahr valley, Germany.

Table B1Sensitivity analysis showing the results of the binary regression analysis for stressors based on Galea et al. (2007), without the predictor suffering severe injury/illness during the event, considering the binary indication for PTSD or non-PTSD cases.

Data is available from the authors upon reasonable request.

MLZ, PB, and AT conceptualized the study and participated in data collection. MLZ conducted the analyses. PB contributed to parts of the methods sections, while MLZ authored and visualized the initial draft, which underwent review and editing by all co-authors. MLZ finalized the paper for submission under the supervision of PB and AT.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors.

This article is part of the special issue “Strengthening climate-resilient development through adaptation, disaster risk reduction, and reconstruction after extreme events”. It is not associated with a conference.

We thank all respondents for participating in the survey.

This research was funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung – BMBF) under the Project “KAHR – Climate Adaptation, Floods and Resilience” (grant no. FKZ 01LR2102I).

This paper was edited by Marvin Ravan and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Alfieri, L., Burek, P., Feyen, L., and Forzieri, G.: Global warming increases the frequency of river floods in Europe, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 19, 2247–2260, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-19-2247-2015, 2015.

Alonso, J., Angermeyer, M. C., Bernert, S., Bruffaerts, R., Brugha, T. S., Bryson, H., de Girolamo, G., Graaf, R., Demyttenaere, K., Gasquet, I., Haro, J. M., Katz, S. J., Kessler, R. C., Kovess, V., Lépine, J. P., Ormel, J., Polidori, G., Russo, L. J., Vilagut, G., Almansa, J., Arbabzadeh-Bouchez, S., Autonell, J., Bernal, M., Buist-Bouwman, M. A., Codony, M., Domingo-Salvany, A., Ferrer, M., Joo, S. S., Martínez-Alonso, M., Matschinger, H., Mazzi, F., Morgan, Z., Morosini, P., Palacín, C., Romera, B., Taub, N., and Vollebergh, W. A. M.: Prevalence of mental disorders in Europe: results from the European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD) project, Acta Psych. Neurol. Su., 21–27, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0047.2004.00327.x, 2004.

American Psychiatric Association (Ed.): Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, DSM-IV, American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc., ISBN 0-89042-061-0, 1994.

Apel, D. and Coenen, M.: Mental health and health-related quality of life in victims of the 2013 flood disaster in Germany – A longitudinal study of health-related flood consequences and evaluation of institutionalized low-threshold psycho-social support, Int. J. Disast. Risk Re., 58, 102179, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2021.102179, 2021.

Atwoli, L., Stein, D. J., King, A., Petukhova, M., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Alonso, J., Bromet, E. J., De Girolamo, G., Demyttenaere, K., Florescu, S., Maria Haro, J., Karam, E. G., Kawakami, N., Lee, S., Lepine, J.-P., Navarro-Mateu, F., O'Neill, S., Pennell, B.-E., Piazza, M., Posada-Villa, J., Sampson, N. A., Ten Have, M., Zaslavsky, A. M., Kessler, R. C., and on behalf of the WHO World Mental Health Survey Collaborators: Posttraumatic stress disorder associated with unexpected death of a loved one: Cross-national findings from the world mental health surveys: ATWOLI ET AL, Depress. Anxiety, 34, 315–326, https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22579, 2017.

Babcicky, P., Seebauer, S., and Thaler, T.: Make it personal: Introducing intangible outcomes and psychological sources to flood vulnerability and policy, Int. J. Disast. Risk Re., 58, 102169, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2021.102169, 2021.

Bei, B., Bryant, C., Gilson, K.-M., Koh, J., Gibson, P., Komiti, A., Jackson, H., and Judd, F.: A prospective study of the impact of floods on the mental and physical health of older adults, Aging Ment. Health, 17, 992–1002, https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2013.799119, 2013.

Brady, K. T., Killeen, T. K., Brewerton, T., and Lucerini, S.: Comorbidity of psychiatric disorders and posttraumatic stress disorder, J. Clin. Psychiat., 61 , 22–32, 2000.

Breslau, N., Peterson, E. L., Kessler, R. C., and Schultz, L. R.: Short screening scale for DSM-IV posttraumatic stress disorder, Am. J. Psychiat., 156, 908–911, https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.156.6.908, 1999.

Bromet, E. J., Atwoli, L., Kawakami, N., Navarro-Mateu, F., Piotrowski, P., King, A. J., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Alonso, J., Bunting, B., Demyttenaere, K., Florescu, S., de Girolamo, G., Gluzman, S., Haro, J. M., de Jonge, P., Karam, E. G., Lee, S., Kovess-Masfety, V., Medina-Mora, M. E., Mneimneh, Z., Pennell, B.-E., Posada-Villa, J., Salmerón, D., Takeshima, T., and Kessler, R. C.: Post-traumatic stress disorder associated with natural and human-made disasters in the World Mental Health Surveys, Psychol. Med., 47, 227–241, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291716002026, 2017.

Bubeck, P. and Thieken, A. H.: What helps people recover from floods? Insights from a survey among flood-affected residents in Germany, Reg. Environ. Change, 18, 287–296, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-017-1200-y, 2018.

Bundesamt für Kartographie und Geodäsie (BKG): GeoBasis-DE: Verwaltungsgebiete 1:5 000 000, Stand 01.01. (VG5000 01.01.), dl-de/by-2-0, GeoBasis-DE/BKG [data set], https://gdz.bkg.bund.de/index.php/default/digitale-geodaten/verwaltungsgebiete/verwaltungsgebiete-1-5-000-000-stand-01-01-vg5000-01-01.html (last access: 5 January 2024), 2024.

Bundesanstalt für Gewässerkunde (BfG): Waterbody-DE. Waterbody as ESRI file geodatabase, ETRS89 (non INSPIRE conformant), WasserBLIcK/BfG und Zuständige Behörden der Länder [data set], https://geoportal.bafg.de/inspire/download/HY/waterbody/datasetfeed.xml (last access: 5 January 2024), 2023.

CRED and UNDRR: Human costs of disasters. An overview of the last 20 years, CRED and UNDRR, https://www.preventionweb.net/files/74124_humancostofdisasters20002019reportu.pdf (last access: 16 August 2024), 2020.

Deutsche Bahn: Zerstörungen in historischem Ausmaß: DB zieht nach Flutkatastrophe Zwischenbilanz, https://www.deutschebahn.com/de/presse/pressestart_zentrales_ uebersicht/Zerstoerungen-in-historischem-Ausmass-DB-zieht-nach-Flutkatastrophe-Zwischenbilanz-6868360, last access: 17 May 2022.

DH Emergency Preparedness Division: Emergency Planning Guidance: Planning for the Psychosocial and Mental Health Care of People Affected by Major Incidents and Disasters, DH Emergency Preparedness Division, London, https://www.coe.int/t/dg4/majorhazards/ressources/virtuallibrary/materials/UK/dh_103563.pdf (last access: 16 August 2024), 2009.

Dietze, M., Bell, R., Ozturk, U., Cook, K. L., Andermann, C., Beer, A. R., Damm, B., Lucia, A., Fauer, F. S., Nissen, K. M., Sieg, T., and Thieken, A. H.: More than heavy rain turning into fast-flowing water – a landscape perspective on the 2021 Eifel floods, Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci., 22, 1845–1856, https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-22-1845-2022, 2022.

Dreßing, H. and Foerster, K.: Traumafolgestörungen in ICD-10, ICD-11 und DSM-5, Forensische Psychiatr. Psychol. Kriminol., 15, 47–53, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11757-020-00645-6, 2021.

Eurostat/GISCO: NUTS, European Commission – Eurostat/GISCO, EuroGeographics and TurkStat [data set], https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/de/web/gisco/geodata/reference-data/administrative-units-statistical-units/nuts (last access: 5 January 2024), 2021.

Fekete, A. and Sandholz, S.: Here Comes the Flood, but Not Failure? Lessons to Learn after the Heavy Rain and Pluvial Floods in Germany 2021, Water, 13, 3016, https://doi.org/10.3390/w13213016, 2021.

Fernández, A., Black, J., Jones, M. K., Wilson, L., Salvador-Carulla, L., Astell-Burt, T., and Black, D.: Flooding and Mental Health: A Systematic Mapping Review, PLoS ONE, 10, 31, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0119929, 2015.

Frans, Ö., Rimmö, P.-A., Åberg, L., and Fredrikson, M.: Trauma exposure and post-traumatic stress disorder in the general population, Acta Psych. Neurol., 111, 291–290, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2004.00463.x, 2005.

Galatzer-Levy, I. R., Nickerson, A., Litz, B. T., and Marmar, C. R.: Patterns Of Lifetime PTSD Comorbidity: A Latent Class Analysis: Research Article: Patterns of Lifetime PTSD Comorbidity, Depress. Anxiety, 30, 489–496, https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22048, 2013.

Galea, S., Nandi, A., and Vlahov, D.: The epidemiology of post-traumatic stress disorder after disasters, Epidemiol. Rev., 27, 78–91, https://doi.org/10.1093/epirev/mxi003, 2005.

Galea, S., Brewin, C. R., Gruber, M., Jones, R. T., King, D. W., King, L. A., McNally, R. J., Ursano, R. J., Petukhova, M., and Kessler, R. C.: Exposure to hurricane-related stressors and mental illness after Hurricane Katrina, Arch. Gen. Psychiat., 64, 1427–1434, https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.64.12.1427, 2007.

Golitaleb, M., Mazaheri, E., Bonyadi, M., and Sahebi, A.: Prevalence of Post-traumatic Stress Disorder After Flood: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis, Front. Psychiatry, 13, 890671, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.890671, 2022.

Graham, H., White, P., Cotton, J., and McManus, S.: Flood- and Weather-Damaged Homes and Mental Health: An Analysis Using England's Mental Health Survey, Int. J. Env. Res. Pub. He, 16, 3256, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16183256, 2019.

Jacobi, F., Höfler, M., Strehle, J., Mack, S., Gerschler, A., Scholl, L., Busch, M. A., Maske, U., Hapke, U., Gaebel, W., Maier, W., Wagner, M., Zielasek, J., and Wittchen, H.-U.: Psychische Störungen in der Allgemeinbevölkerung: Studie zur Gesundheit Erwachsener in Deutschland und ihr Zusatzmodul Psychische Gesundheit (DEGS1-MH), Nervenarzt, 85, 77–87, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00115-013-3961-y, 2014.

Jermacane, D., Waite, T. D., Beck, C. R., Bone, A., Amlôt, R., Reacher, M., Kovats, S., Armstrong, B., Leonardi, G., James Rubin, G., and Oliver, I.: The English National Cohort Study of Flooding and Health: the change in the prevalence of psychological morbidity at year two, BMC Public Health, 18, 330, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5236-9, 2018.

Jongman, B., Ward, P. J., and Aerts, J. C. J. H.: Global exposure to river and coastal flooding: Long term trends and changes, Glob. Environ. Chang., 22, 823–835, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2012.07.004, 2012.

Jongman, B., Hochrainer-Stigler, S., Feyen, L., Aerts, J. C. J. H., Mechler, R., Botzen, W. J. W., Bouwer, L. M., Pflug, G., Rojas, R., and Ward, P. J.: Increasing stress on disaster-risk finance due to large floods, Nat. Clim. Change, 4, 264–268, https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2124, 2014.

Junghänel, T., Bissolli, P., Daßler, J., Fleckenstein, R., Imbery, F., Janssen, W., Kaspar, F., Lengfeld, K., Leppelt, T., Rauthe, M., Rauthe-Schöch, A., Rocek, M., Walawender, E., and Weigl, E.: Hydro-klimatologische Einordnung der Stark- und Dauerniederschläge in Teilen Deutschlands im Zusammenhang mit dem Tiefdruckgebiet “Bernd” vom 12. bis 19. Juli 2021, Deutscher Wetterdienst, https://www.dwd.de/DE/leistungen/besondereereignisse/niederschlag/20210721_bericht_starkniederschlaege_tief_bernd.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=10 (last access: 16 August 2024), 2021.

Keya, T. A., Leela, A., Habib, N., Rashid, M., and Bakthavatchalam, P.: Mental Health Disorders Due to Disaster Exposure: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis, Cureus, 15, e37031, https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.37031, 2023.

Keyes, K. M., Pratt, C., Galea, S., McLaughlin, K. A., Koenen, K. C., and Shear, M. K.: The Burden of Loss: Unexpected Death of a Loved One and Psychiatric Disorders Across the Life Course in a National Study, Am. J. Psychiat., 171, 864–871, https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13081132, 2014.

Kimerling, R., Ouimette, P., Prins, A., Nisco, P., Lawler, C., Cronkite, R., and Moos, R. H.: Brief report: Utility of a short screening scale for DSM-IV PTSD in primary care, J. Gen. Intern. Med., 21, 65–67, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.00292.x, 2006.

Kreibich, H., Thieken, A. H., Petrow, Th., Müller, M., and Merz, B.: Flood loss reduction of private households due to building precautionary measures – lessons learned from the Elbe flood in August 2002, Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci., 5, 117–126, https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-5-117-2005, 2005.

Kron, W., Eichner, J., and Kundzewicz, Z. W.: Reduction of flood risk in Europe – Reflections from a reinsurance perspective, J. Hydrol., 576, 197–209, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2019.06.050, 2019.

Kron, W., Bell, R., Thiebes, B., and Thieken, A.: The July 2021 flood disaster in Germany, in: 2022 HELP Global Report on Water and Disasters, High-level Experts and Leaders Panel on Water and Disasters (HELP), Tokyo, 12–44, https://dkkv.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/HELP_Global_Report_2022.pdf (last access: 16 August 2024), 2022.

Lamond, J. E., Joseph, R. D., and Proverbs, D. G.: An exploration of factors affecting the long term psychological impact and deterioration of mental health in flooded households, Environ. Res., 140, 325–334, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2015.04.008, 2015.

Laudan, J., Zöller, G., and Thieken, A. H.: Flash floods versus river floods – a comparison of psychological impacts and implications for precautionary behaviour, Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci., 20, 999–1023, https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-20-999-2020, 2020.

Lowe, D., Ebi, K. L., and Forsberg, B.: Factors increasing vulnerability to health effects before, during and after floods, Int. J. Env. Res. Pub. He., 10, 7015–7067, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph10127015, 2013.

Maercker, A., Hecker, T., Augsburger, M., and Kliem, S.: ICD-11 Prevalence Rates of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Complex Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in a German Nationwide Sample, J. Nerv. Ment. Dis., 206, 270–276, https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000000790, 2018.

Mason, V., Andrews, H., and Upton, D.: The psychological impact of exposure to floods, Psychol. Health Med., 15, 61–73, https://doi.org/10.1080/13548500903483478, 2010.

Merz, B., Elmer, F., Kunz, M., Mühr, B., Schröter, K., and Uhlemann-Elmer, S.: The extreme flood in June 2013 in Germany, Houille Blanche, 100, 5–10, https://doi.org/10.1051/lhb/2014001, 2014.

Munich Re: Schadenereignisse in Deutschland 1980–2017, NatCatSERVICE, https://www.ergo.com/-/media/ergocom/pdf-mediathek/naturgefahren/1980-2017-naturgefahren-deutschland-natcatservice.pdf (last access: 16 August 2024), 2018.

Munich Re: Hurricanes, cold waves, tornadoes: Weather disasters in USA dominate natural disaster losses in 2021, https://www.munichre.com/en/company/media-relations/media-information-and-corporate-news/media-information/2022/natural-disaster-losses-2021.html (last access: 22 December 2023), 2022.

National Mental Health Commission: National disaster mental health and wellbeing framework, Supporting Australians' mental health through disaster, National Mental Health Commission, https://nema.gov.au/sites/default/files/inline-files/28108 NEMA National Disaster Mental Health and Wellbeing Framework FA v4.pdf (last access: 16 August 2024), 2023.

Nitschke, M., Einsle, F., Lippmann, C., Simonis, G., Köllner, V., and Strasser, R. H.: Emergency evacuation of the Dresden Heart Centre in the flood disaster in Germany 2002: perceptions of patients and psychosocial burdens, Int. J. Disast. Med., 4, 118–124, https://doi.org/10.1080/15031430601138290, 2006.

Norris, F. H., Friedman, M. J., and Watson, P. J.: 60,000 disaster victims speak: Part II. Summary and implications of the disaster mental health research, Psychiatry, 65, 240–260, https://doi.org/10.1521/psyc.65.3.240.20169, 2002.

Norris, M. and Lecavalier, L.: Evaluating the Use of Exploratory Factor Analysis in Developmental Disability Psychological Research, J. Autism Dev. Disord., 40, 8–20, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-009-0816-2, 2010.

Paprotny, D., Morales-Nápoles, O., and Jonkman, S. N.: HANZE: a pan-European database of exposure to natural hazards and damaging historical floods since 1870, Earth Syst. Sci. Data, 10, 565–581, [dataset], https://doi.org/10.4121/uuid:5b75be6a-4dd4-472e-9424-f7ac4f7367f6, 2018.

Paranjothy, S., Gallacher, J., Amlôt, R., Rubin, G. J., Page, L., Baxter, T., Wight, J., Kirrage, D., McNaught, R., and Sr, P.: Psychosocial impact of the summer 2007 floods in England, BMC Public Health, 11, 145, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-145, 2011.

Puechlong, C., Weiss, K., Le Vigouroux, S., and Charbonnier, E.: Role of personality traits and cognitive emotion regulation strategies in symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder among flood victims, Int. J. Disast. Risk Re., 50, 101688, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101688, 2020.

Pulcino, T., Galea, S., Ahern, J., Resnick, H., Foley, M., and Vlahov, D.: Posttraumatic Stress in Women after the September 11 Terrorist Attacks in New York City, J. Womens Health, 12, 809–820, https://doi.org/10.1089/154099903322447774, 2003.

Schwarz, E. D. and Kowalski, J. M.: Posttraumatic stress disorder after a school shooting: effects of symptom threshold selection and diagnosis by DSM-III, DSM-III-R, or proposed DSM-IV, Am. J. Psychiat., 148, 592–597, https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.148.5.592, 1991.

Seidler, Z. E., Rice, S. M., Ogrodniczuk, J. S., Oliffe, J. L., Shaw, J. M., and Dhillon, H. M.: Men, masculinities, depression: Implications for mental health services from a Delphi expert consensus study, Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract., 50, 51–61, https://doi.org/10.1037/pro0000220, 2019.

Seneviratne, S. I., Zhang, X., Adnan, M., Badi, W., Dereczynski, C., Di Luca, A., Ghosh, S., Iskandar, I., Kossin, J., Lewis, S., Otto, F., Pint, I., Sato, M., Vicente-Serranno, S. M., Wehn, M., and Zho, B.: Weather and Climate Extreme Events in a Changing Climate, in Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, in: Climate Change 2021 – The Physical Science Basis: Working Group I Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, edited by: Intergovernmental Panel On Climate Change, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 1513–1766, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157896, 2021.

Siegrist, P. and Maercker, A.: Deutsche Fassung der Short Screening Scale for DSM-IV Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Aktueller Stand der Validierung, Trauma Gewalt, 4, 208-213–213, 2010.

Stanke, C., Murray, V., Amlôt, R., Nurse, J., and Williams, R.: The effects of flooding on mental health: Outcomes and recommendations from a review of the literature, PLoS Curr., 4, e4f9f1fa9c3cae, https://doi.org/10.1371/4f9f1fa9c3cae, 2012.

Statistical Office Rhineland-Palatinate (RP): Fast 24,5 Millionen Euro Soforthilfen an private Haushalte im Ahrtal ausgezahlt, https://www.statistik.rlp.de/nachrichten/nachichtendetailseite/fast-245-millionen-euro-soforthilfen-an-private-haushalte-im-ahrtal-ausgezahlt-innenminister-lewentz-dankt-statistischem-landesamt (last access: 19 August 2024), 2021.

Statistical Office Rhineland-Palatinate (RLP): Demografischer Wandel in Rheinland-Pfalz. Sechste regionalisierte Bevölkerungsvorausberechnung (Basisjahr 2020). Ergebnisse für den Landkreis Ahrweiler, https://www.statistik.rlp.de/fileadmin/dokumente/stat_analysen/RP_2070/kreis/131.pdf (last access: 18 August 2024), 2022.

Statistical Office Rhineland-Palatinate (RLP): Verfügbares Einkommen der privaten Haushalte, Statistische Monatshefte 1, https://www.statistischebibliothek.de/mir/servlets/MCRFileNodeServlet/RPMonografie_derivate_00000331/01_2023_Volkswirtschaft.pdf (last access: 19 August 2024), 2023.

Statistical Office Rhineland-Palatinate (RLP): Bevölkerung der Gemeinden am 30. Juni 2022, Statistische Berichte, https://www.statistischebibliothek.de/mir/servlets/MCRFileNodeServlet/RPHeft_derivate_00008228/A1033_202221_hj_G.pdf (last access: 19 August 2024), 2024.

Tapsell, S.: Socio-Psychological Dimensions of Flood Risk Management, in: Flood Risk Science and Management, edited by: Pender, G. and Faulkner, H., Wiley, 407–428, https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444324846.ch20, 2010.

Thieken, A. H., Müller, M., Kreibich, H., and Merz, B.: Flood damage and influencing factors: New insights from the August 2002 flood in Germany, Water Resour. Res., 41, 2005WR004177, https://doi.org/10.1029/2005WR004177, 2005.

Thieken, A. H., Bessel, T., Kienzler, S., Kreibich, H., Müller, M., Pisi, S., and Schröter, K.: The flood of June 2013 in Germany: how much do we know about its impacts?, Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci., 16, 1519–1540, https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-16-1519-2016, 2016.

Thieken, A., Bubeck, P., and Zenker, M.-L.: Fatal incidents during the flood of July 2021 in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany: what can be learnt for future flood risk management?, J. Coast. Riverine Flood Risk, 2, paper 5, https://doi.org/10.59490/jcrfr.2023.0005, 2023a.

Thieken, A. H., Bubeck, P., Heidenreich, A., von Keyserlingk, J., Dillenardt, L., and Otto, A.: Performance of the flood warning system in Germany in July 2021 – insights from affected residents, Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci., 23, 973–990, https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-23-973-2023, 2023b.

Tradowsky, J. S., Philip, S. Y., Kreienkamp, F., Kew, S. F., Lorenz, P., Arrighi, J., Bettmann, T., Caluwaerts, S., Chan, S. C., De Cruz, L., De Vries, H., Demuth, N., Ferrone, A., Fischer, E. M., Fowler, H. J., Goergen, K., Heinrich, D., Henrichs, Y., Kaspar, F., Lenderink, G., Nilson, E., Otto, F. E. L., Ragone, F., Seneviratne, S. I., Singh, R. K., Skålevåg, A., Termonia, P., Thalheimer, L., Van Aalst, M., Van Den Bergh, J., Van De Vyver, H., Vannitsem, S., Van Oldenborgh, G. J., Van Schaeybroeck, B., Vautard, R., Vonk, D., and Wanders, N.: Attribution of the heavy rainfall events leading to severe flooding in Western Europe during July 2021, Clim. Change, 176, 90, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-023-03502-7, 2023.