the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Risk reduction through managed retreat? Investigating enabling conditions and assessing resettlement effects on community resilience in Metro Manila

Hannes Lauer

Carmeli Marie C. Chaves

Evelyn Lorenzo

Sonia Islam

Jörn Birkmann

Managed retreat, a key strategy in climate change adaptation for areas with high hazard exposure, raises concerns due to its disruptive nature, vulnerability issues and overall risk in the new location. On-site upgrading or near-site resettlement is seen as more appropriate and effective compared to a relocation far from the former place of living. However, these conclusions often refer to only a very limited set of empirical case studies or do not sufficiently consider different context conditions and phases in resettlement. Against this background, this paper examines the conditions and factors contributing to community resilience of different resettlement projects in Metro Manila. In this urban agglomeration reside an estimated 500 000 informal households, with more than 100 000 occupying high-risk areas. In light of the already realized and anticipated climate change effects, this precarious living situation exposes families, already socio-economically vulnerable, to an increased risk of flooding. The response of the Philippine government to the vexing problem of informal dwellers has been large-scale resettlement from coasts, rivers and creeks to state-owned sites at urban fringes. However, only very few resettlement projects could be realized as in-city projects close to the original living space. The study employs a sequential mixed-method approach, integrating a large-scale quantitative household survey and focus group discussions (FGDs) for a robust comparison of resettlement types. Further, it reveals community-defined enabling factors for managed retreat as climate change adaptation strategy.

Results indicate minor variations in well-being conditions between in-city and off-city resettlement, challenging the expected impact of a more urban setting on resilience. Instead, essential prerequisites for resettlement involve reduced hazard exposure, secure tenure and safety from crime. Beyond these essential conditions, social cohesion and institutional support systems emerge as significant influencers for the successful establishment of well-functioning new settlements. With this findings, the study contributes to the expanding body of literature on managed retreat, offering a comprehensive evaluation based on extensive datasets and providing entry points for the improvement of retreat as a climate change adaptation strategy.

- Article

(1966 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

Planned relocation or managed retreat is an increasingly accepted adaptation strategy to mitigate the potential effects of climate-induced hazards such as flood disasters or sea level rise (Haasnoot et al., 2021; Mach and Siders, 2021; Ferris and Weerasinghe, 2020; Carey, 2020; Greiving et al., 2018; Hino et al., 2017; IPCC, 2014). Often, this entails uprooting entire communities and transferring them to safer locations where families can start anew without the constant threat of disasters and displacement. However, moving families out of harm's way is not synonymous with building their capacity to stem disaster impacts, much less catalysing their recovery from disruptions. Beyond a change in residence, managed retreat has to be an enabling process for communities (Arnall, 2019).

This holds particular significance in the context of the Philippines and Metro Manila, where relocation or resettlement (resettlement is the commonly used term in the Philippines) efforts principally target the most vulnerable, namely those 100 000 residing in informal settlements (Alvarez, 2019; Ballesteros and Egana, 2013). The Philippines has a long-standing tradition of resettlement, primarily associated with slum clearance initiatives and development projects, such as highway construction (Lauer et al., 2021; Ajibade, 2019). More recently, and notably following the devastating effects of Typhoon Ondoy in 2009 (international name: Ketsana), there have been ambitious plans to resettle the people living in designated danger areas (Alvarez, 2019; Galuszka, 2019; Ballesteros and Egana, 2013) as an integral part of disaster risk reduction strategies and intentions to flood-proof the city (Ajibade, 2019; Alvarez, 2019). One concern arises in this context, namely that there is no clarity and consensus on the definition and declaration of danger areas (Republic of the Philippines, 2022). In most cases, they refer only to the national water code from 1976 that defines no-build zones as a buffer of 3 m around waterbodies in urban areas. Thus, danger areas are not necessarily areas with a distinct flood probability or taking vulnerable and sensitive elements into account, nor do they consider future climate change impacts and associated risks. These risks are significant, when regarding, for example, that storm surges in the wake of typhoons are already threatening vast areas of the urbanized Metro Manila coastline and kilometres of hinterland (Lapidez et al., 2015; Tablazon et al., 2015) and that rising sea levels are accelerated by rapid land subsidence in the region (Cao et al., 2021; Jevrejeva et al., 2016; Rodolfo and Siringan, 2006). The second concern in the context of danger zone resettlement is that the default strategy of resettlement in Metro Manila has always been large-scale off-city settlements where the so-called beneficiaries are relocated in a top-down manner to the periphery of the national capital region (NCR) or even to rural regions in neighbouring provinces (Galuszka, 2020; Jensen et al., 2020b; Ballesteros and Egana, 2013). On the other hand, only a few examples of in-city settlements, where individuals are resettled within the same municipality in rather close proximity to their original living space, exist. Therefore critics argue that current resettlement activities are a new form of eviction in the name of saving lives (Alvarez, 2019) and leading to significant disruption to the lives of the resettled people (Mateo, 2022; Jensen et al., 2020a; Tadgell et al., 2017).

While managed retreat gains global traction as a climate change adaptation and risk reduction strategy, and resettlement has become a central component of urban development in Metro Manila, there is a noticeable gap in the evaluation of resettlement practices. Moreover, the expanding literature on managed retreat also lacks robust comparisons and evaluations using extensive datasets (Haasnoot et al., 2021; Greiving et al., 2018), indicating that the current and long-term impacts of managed retreat remain inadequately assessed in terms of success or effectiveness (Hoang and Noy, 2020), whereby the challenge starts already in defining what success should mean for retreat (Ajibade et al., 2022; de Sherbinin et al., 2011). Against this background, this study holds particular significance as it aims to contribute to filling this gap by evaluating and scrutinizing the suitability of retreat as an adaptation strategy and providing insights into the living conditions of resettled communities. What distinguishes this study is its approach – the success or the effectiveness of resettlement is defined by the resettled communities themselves, meaning that the communities resettled from flood-affected informal settlements identified elements crucial for their community resilience. These elements are considered as community-defined enabling factors for resilient retreat and serve in this study as categories for the assessment. Apart from the desire to distil these enabling factors, the two research questions based thereon are as follows. (1) Are resettlement practices in the Philippines deemed successful when assessing these community-defined enabling factors? (2) Are there significant disparities when comparing in-city resettlement projects with their off-city counterparts?

In pursuit of the research objective and exploration of these research questions, the study employs a comprehensive mixed-method approach with a large-scale quantitative household survey and focus group discussions (FGDs). The FGDs revealed the community perceptions of what accounts for community resilience in the context of their settlement, while the quantitative household survey provided essential data for analysing the defined enabling factors. Drawing from these first hand experiences and robust data, the study explores the essential conditions that contribute to the effectiveness of resettlement efforts at the household level.

The following second section sets the stage by delving into the state of the research field of retreat as hazard prevention and climate change adaptation strategy as well as into the historical context and contemporary landscape of resettlement practices in the Philippines. Section 3 elaborates the applied methodology. It describes the study design and informs about the conducted survey and the FGDs. Section 4 provides the results derived from the applied methods, while Sect. 5 offers a synthesis. The final Sect. 6 concludes by revisiting the initial research objective and further contextualizes the results within the realm of policy implications.

2.1 Retreat, resettlement in the context of climate change and habitability

Climate change is a significant risk amplifier, impacting both slow and sudden onset hazards (Birkmann and Lauer, 2022): sea level rise and salinization are threatening coastal regions, home to hundreds of millions (Glavovic et al., 2023; Kulp and Strauss, 2019). Extreme heat endangers human well-being, while extreme rain and storm events are likely to become more frequent and intense (Lee et al., 2023). These changes often impact areas already exposed to severe hazards, raising concerns about habitability. This discussion revolves around which regions will support healthy and sustainable living or even survival – today but especially in a world projected to be 2 or 3 °C warmer (Mach and Siders, 2021). Exploring habitability involves understanding potential thresholds in three dimensions: basic human survival, livelihood security and the capacities of societies to manage environmental risk (Horton et al., 2021). Within this context, discussions are increasingly concerned about present and future migration triggered by environmental and climate change, coupled with societal factors (Sakdapolrak et al., 2023; Szaboova et al., 2023; McLeman et al., 2021; Hauer et al., 2020; Scott et al., 2020; McLeman, 2018; Adams, 2016; Black et al., 2011). One form of such migration influenced by climate and environmental change is managed retreat, here defined as the deliberate and permanent movement of people (and/or infrastructure) away from hazard-prone areas to reduce the hazard exposure (Lauer et al., 2021). Retreat is primarily a scientific strategy, whereas resettlement and relocation are its practical components, often used interchangeably by stakeholders. Now as climate change is amplifying existing hazards and therewith risks, it is also amplifying resettlement activities. Certainly, resettlement is nothing new. It has been a relevant topic before climate change, and would remain critical even in the absence of future climate impacts. This is because it intertwines with ongoing planning discussions involving topics such as urban poverty, the right to the city, gentrification, social housing, equality, rapid urban growth or disaster risk reduction. However, its significance is set to increase tremendously under conditions of climate change (Haasnoot et al., 2021; Mach and Siders, 2021; Scott et al., 2020;). Government-led or planned resettlement to safeguard populations at risk from disasters aligns with the conception of planned adaptation. Planned adaptation arises from decisions rooted in recognizing changing conditions or anticipated changes, necessitating actions to attain, maintain or return to a desired state. These actions might involve interventions to prevent, tolerate, spread the loss or change location. These measures can be further classified by their function as protect, accommodate or retreat (IPCC, 2014). However, the choice of any planned adaptation action is value-laden, requiring governments to make prior decisions about what to preserve, alter or permit to stay its course. Planned adaptation decisions are commonly made at superordinate national levels, and it is thus criticized that government policies and practices might be inadequate to take into account context-specific vulnerability–poverty linkages (Rahman and Hickey, 2019). In most cases, the initial response of planned adaptation is to protect what is valued. If not possible, the approach is to accommodate and bear certain losses. The last resort is to retreat from a location when spreading the loss is no longer viable. While this argument merits rights-based policy discourse, disaster-prone countries like the Philippines will assert the moral imperative to protect their population and resources from imminent risk as a precaution to prevent or stem future loss and damage.

Besides the conceptual or heuristic examination of planned or managed retreat, it can be assumed that on the practical level, it builds mainly on existing practices of resettlement. It is unlikely that resettlement practice would dramatically change all of a sudden, solely as hazard risk and climate change are proclaimed as reasons for relocating people. Considering the significant risks associated with resettlement (Ajibade et al., 2022; Dannenberg et al., 2019; Rogers and Wilmsen, 2019; Maldonado et al., 2013; De Wet, 2006; Cernea, 1997; Scudder, 1993), it would pose potential problems when existing resettlement strategies and practices were merely continued or even extended under the guise of risk prevention as managed retreat. This might further be difficult, as it can be estimated that informal settlers are very sensitive to the fact that , based on their experience with land interest and development-induced resettlement, the land they are living on is of value and the actual reasons of their proposed resettlement might be other than for their safety (Lorenzo Pérez and Contreras, 2022; Saguin and Alvarez, 2022; Alvarez, 2019). Therefore, it is crucial to scrutinize and evaluate current practices and policies, aiming to identify enabling conditions that facilitate resilient forms of retreat, steering clear of previous or current mistakes being made in resettlement practice.

2.2 Resettlement as adaptation in Metro Manila, Philippines

Resettlement in Metro Manila mainly deals with relocating the urban poor, especially those in informal settlements (Jensen et al., 2020a). Since the 1960s and 1970s, various policies and programmes targeted informality, ranging from public housing to slum upgrading and centralized resettlement applying a low-rise housing typology to the outskirts of the urban areas (Lauer et al., 2021; Du and Greiving, 2020; Galuszka, 2020; Ballesteros, 2002). Despite these multiple efforts, coordinated centrally by the National Housing Authority (NHA) since its establishment in 1975, major challenges in the housing sector persist. These include a significant housing backlog, high homelessness rates and a substantial population residing in informal settlements (UN-Habitat, 2023).

Initially, resettlement served as an instrument for slum clearance to address tenure issues or to cater to private interests. Later, the focus shifted towards infrastructure development and the rehabilitation of public spaces (Delos Reyes and Francisco, 2015; Jensen et al., 2020a). Since the end of the 2000s, environmental and risk concerns created an urgency and motif for relocating families. In 2008, the Supreme Court issued a writ of continuing mandamus instructing different government departments and agencies to clean up and rehabilitate Manila Bay to a quality of water fit for swimming and other recreational activities. This clean-up initiative was extended to rivers and major tributaries feeding into the bay. Integral to the rehabilitation effort is the intensified conservation of buffers for waterways in urban areas by removing illegal structures in the 3 m easement area, which was also named a danger area. In the wake of this directive, Typhoon Ondoy wrought unprecedented havoc in Metro Manila and adjacent provinces, which bolstered the clearing operations anew. Resettlement then took a different impetus. By 2011, the newly installed administration initiated a 5-year resettlement programme called the Oplan Lumikas para Iwas Kalamidad at Sakit (LIKAS), which aimed to relocate roughly 120 000 informal settler families (ISFs) from the danger areas along major waterways in Metro Manila to other parts of the metropolis and neighbouring provinces (Galuszka, 2020). The government earmarked PHP 50 billion in funding to produce 120 868 dwelling units for qualified informal settler families within and around Metro Manila to respond to the court order while addressing the long-drawn clamour for housing by a ballooning IS population estimated to be around 1.2 million in NCR alone (World Bank, 2017). By the end of the programme, the Department of the Interior and Local Government (DILG) reported that the programme completed around 73.5 % of the targeted housing units (Galuszka, 2019). Over 80 % of these structures were established in off-city resettlement projects (Galuszka, 2018), an approach that Ballesteros (2017) described to be less effective in delivering the expected socio-economic benefits. This observation resonates with recent legislative reforms to institutionalize in-city resettlement over off-city options (Republic of the Philippines, 2022, 2017). Despite this articulated push for in-city resettlement, practical challenges remain, and thus, large off-city developments are still the default and more easily replicable strategy. Several factors come into play, including the availability of affordable or suitable lands for socialized housing in Metro Manila, the quantity of families to be relocated, or the urgency for fast-processing resettlement of informal settlers.

The discussion about off-city and in-city resettlement is still a controversial and intensively debated topic within the discourse on resettlement, underlining the argument that relocating to off-city sites may disrupt existing livelihoods and potentially lead to a high risk of impoverishment and, in some cases, even a return to informal urban areas (Mateo, 2022; Tadgell et al., 2017; Jensen et al., 2020a; Doberstein et al., 2020). This ongoing discourse has gained fresh momentum with the new administration's ambitious plan to develop 1 million housing units annually until 2028 nationwide. This initiative aims to address the massive housing backlog, estimated at around 6 to 6.8 million, and to ultimately eliminate the number of ISFs to zero: “Pambansang Pabahay para sa Pilipino: Zero ISF Program for 2028” (Republic of the Philippines, 2023a, b). According to this political initiative, it is estimated that still 500 000 ISFs live in Metro Manila, with many of them in the designated danger areas, despite the effort brought forward within the Oplan LIKAS programme. Most of their planned resettlement is nowadays intended to be accomplished through the construction of high-rise in-city housing (Republic of the Philippines, 2023b). However, the proposed target of 1 million units per year is highly ambitious, significantly surpassing the current output of the entire housing industry by 7-fold and without even speaking about the financial needs for such a programme (de Guzman, 2023; Katigbak, 2023). Together, the recent efforts to resettle individuals from danger areas, coupled with the ambitious plans to tackle informality, will likely accelerate resettlement activities in the Philippines, especially in Metro Manila. This direction towards rapid and substantial housing delivery for ISFs seems to be leaning more towards a standardized top-down or investor-driven development model. This would contradict the desired co-creation or People's Plan approaches outlined in policy documents and programmes such as in Oplan LIKAS (Galuszka, 2020, 2019). Such alternative resettlement practices would need more diverse housing and programme typologies, financing schemes, and budget allocation, addressing the needs of those being resettled and giving emphasis to social preparation before resettlement and to long-term post-resettlement activities (Lauer et al., 2021).

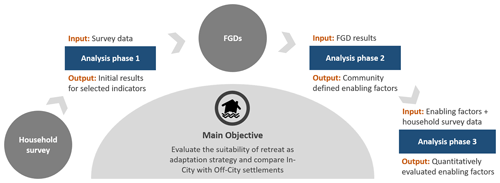

Figure 1Research design illustrating the study objective, methodology and analysis progression. The research commenced with a household survey, followed by analysis phase. (1) Subsequently, the focus group discussions (FGDs) were conducted followed by analysis phase. (2) Thereafter, the final analysis phase (3) integrated FGD outcomes with household survey data.

3.1 Research design

This study follows a sequential multi-method design, where each subsequent step builds upon the method and the findings of the preceding one. Along the 2-year study, the research questions and methods had to be adapted to changing conditions and gained insights. However, the overall underlying research themes are, as can be seen in Fig. 1, to evaluate and scrutinize the suitability of retreat as an adaptation strategy and to compare off-city with in-city settlements. The point of departure in the initial phase of the research was to investigate differences between the two settlement categories by data of a mainly quantitative household survey. The analysis envisaged an assessment and comparison of the hazard exposure and livelihood situation both in the current settlement and in contrast to the former location before the resettlement. The hypothesis was that in-city settlements show better results as the interruption to resettled people's lives is supposed to be smaller. An initial analysis of the data in analysis phase one uncovered partially surprising results (detailed in Sect. 4), in some instances challenging this hypothesis.

Accordingly, to validate and expand upon these results, the next step within the research process was to employ qualitative methods, engaging with residents of two settlements through FGDs. This qualitative approach explored the perception of the community about essential elements that contribute to their resilience in analysis phase two. These community-defined factors were discussed and ranked indicating their importance for the community. They are understood in this research as community-defined enabling factors for resilient retreat. In the last step of the research process, analysis phase three, these enabling factors were then analysed with the prevailing data from the household survey to ultimately deal with the underlying research objective, thus evaluating how the resettlement satisfied these factors. This quantitative evaluation of community-defined factors, investigating retreat effects and successes, is complemented in this research step by narratives from the FGDs.

3.2 Study area and resettlement sites

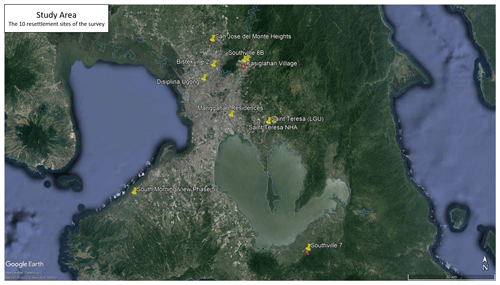

The research was conducted in 10 resettlement sites, comprising three in-city settlements situated within the NCR, commonly referred to as Metro Manila. The remaining seven settlements fall into the category off-city or peripheral near-city settlements, located in the provinces of Bulacan, Rizal, Cavite and Laguna. The selection process is grounded in a pre-established typology of resettlement projects in Metro Manila and surrounding provinces as outlined in prior work (Lauer et al., 2021). Consequently, to ensure a comprehensive overview and encompass the diverse range of resettlement approaches, the study selected settlements exhibiting variations in the four key components: location, programme and finance, strategy, participation, and housing types. It is crucial to note that in the political discussion on resettlement in the Philippines, the primary factor distinguishing settlements is their location. This is mirrored in categorizing settlements as either an in-city or an off-city resettlement type. However, it is essential to recognize that the settlements are divers and can differ from each other even if they are in the same location category. For instance, some off-city settlements, such as those in Cavite and Laguna, are situated at a considerable distance from urban areas, with distances exceeding 40 or even 70 km. On the other hand, certain settlements were originally constructed in rural areas at the fringes of Metro Manila around 20 years ago. But due to the rapid expansion of urban areas in the last decades, some of these settlements are no longer considered highly peripheral.

3.3 Household survey

In the course of the household survey between March and May 2022, a total of 1167 households were interviewed by a team of 12 professional enumerators in the local language Tagalog. The results of 30 households had to be excluded from the analysis because of missing values for important indicators. Accordingly, the final sample size is 1137. The questionnaire consisted of 170 questions, mainly of quantitative nature encompassing yes/no responses, single- and multiple-choice formats, and Likert scale questions. These questions addressed both the individual person surveyed and the household they live in. The questions were structured into the following different thematic areas: (1) resettlement and mobility profile, (2) livelihood (physical, financial, human, social, natural capital), (3) settlement (hazard profile, material and design, planning, and comfort), (4) process (self-organization, co-production and participation, long-term prospect, governance and trust), and (5) respondent household profile.

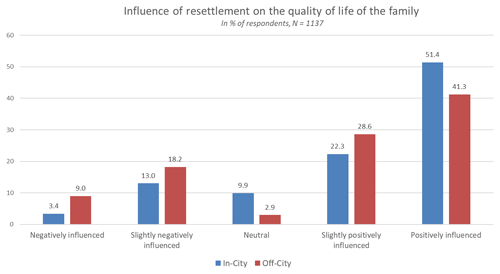

Following the survey, the collected data were digitalized and translated to English. These datasets were then organized within MS Excel and further processed in SPSS, including the necessary coding of questions and variables. The categorization of the settlements with the sample size can be seen in Table 1. The selected sites and the sample reveal that the three settlements categorized as in-city settlements provide 323 respondents, which accounts for 28.5 % of the overall sample size of 1137 respondents.

The sampling method employed in this survey followed a heterogeneous or flexible purposive multi-stage approach. It involved a combination of different probability sampling techniques tailored to the different settlement types. In smaller settlements, the research team initiated the process with a systematic sampling, selecting every xth house, and subsequently utilized a snowball sampling to achieve the desired sample. In larger settlements, the interviews were conducted in all areas or quarters of the settlement, and representatives of the homeowner associations (HOAs), who identified the areas with households that were relocated from waterways, mostly guided the enumerator team. Additionally, snowball sampling was applied. In the case of in-city settlements consisting of medium-rise buildings, each building block was assigned to a specific enumerator who was responsible for conducting systematic and then snowball sampling within the designated block to identify resettled households. This sampling method could ensure that most respondents can be understood as having experienced managed retreat activities. Out of the 1137 respondents 988 or 86.9 % mentioned that the reason for their resettlement was that they were living in a danger area.

3.4 Focus group discussions

The two FGDs took place in October 2022 in the settlements of Kasiglahan Village and Saint Therese Housing (NHA), both situated in Rizal Province. These two settlements, however, have markedly different characteristics. Kasiglahan Village, located in the municipality of Rodriguez, is a relatively aged settlement, established more than 20 years ago. It is a large community with various quarters, named phases, comprising a total of over 9000 housing units. Today, it finds itself in a rather urbanized area as Rodriguez witnessed urbanization processes in the past decades. Notably, Kasiglahan Village has faced severe flooding issues during recent typhoons in some phases of the settlement. Saint Therese Housing, on the other hand, is located in the municipality of Teresa. It is a small settlement with 270 housing units. Although Teresa is in proximity to Antipolo, a rapidly growing city just adjacent to Metro Manila, the settlement itself is situated in a remote, almost rural setting.

Overall, 26 participants provided insights into the community processes, social behaviour and development conditions they perceive to shape community resilience. In both settlements, the FGD participants were long-time residents of the sites. They represented different social groups, namely women, youth, community leaders, fathers, people with disabilities, the elderly and those of the LGBTQ+ community. Recordings and two external observers documented the discussions of the FGDs. MS Excel was used by the research team to code the FGD recordings, identifying the commonly occurring words, conditions and descriptions categorized into the resilience elements.

3.5 Limitations

The applied methods of this study have limitations that warrant acknowledgement and consideration when interpreting the findings. Particularly the household survey is constrained by its sample selection and size, as it only examines a fraction of the total population. Due to financial and organizational constraints, the number of investigated settlements had to be limited to 10 settlements. Thus, a purposeful site selection based on the detailed resettlement typology was essential. The chosen sites mirror the existing distribution, with most existing resettlement sites being off-city sites, providing a broad spectrum of resettlement approaches. However, the diverse nature of the 10 selected settlements, each with unique histories, sizes and features, may, on the other hand, also introduce limitations, necessitating caution when analysing the data for generalized findings.

Temporal aspects present another potential limitation, as settlements vary in age, and thus, the resettled people might find themselves in a different stage of resettlement. While this temporal differentiation offers valuable options for temporal comparisons, it also requires acknowledgement that the respondents may face difficulties recalling the pre-resettlement conditions many years ago. Furthermore, longer-term residency in a settlement can potentially influence the likelihood of experiencing hazards in that very settlement and thereby have an impact on the hazard exposure analysis. However, the whole region experienced a series of severe typhoons in the last years, impacting all surveyed settlements, making it reasonable to assume that the data provide a representative picture of hazard exposure across different sites.

Lastly, also the COVID-19 pandemic posed challenges as the survey took place in early 2022 during the third year of the pandemic and after far-reaching lockdown measures which potentially had a significant impact on the lives and livelihood strategies of the people surveyed.

Considering these limitations, it was crucial to employ the sequential multi-method design, which not only relied on the household survey but also integrated the FGDs as well as various field visits and transect walks.

The results section follows the elaborated research design depicted in Fig. 1. This implies that firstly, the initial comparison between in-city and off-city settlements is presented (analysis phase one), followed by an elaboration of the FGDs which distilled the enabling factors (analysis phase two). Finally, the section concludes with the in-depth analysis of the enabling factors by using the quantitative data (analysis phase three).

4.1 Initial analysis to compare in-city with off-city resettlement

The initial analysis of the survey data encompassed the use of descriptive statistics such as exploratory data analysis or frequency distribution for most indicators. An interesting first result is that when comparing the settlements regarding hazard exposure and livelihood outcomes we found that the difference between surveyed settlement categories (such as off-city versus in-city) was less significant than expected, meaning that solely minor variations could be found when comparing the seven off-city settlements with the three in-city settlements. Even for some indicators the off-city category encompassed better results, and thus in some cases the settlement with the best results was an off-city settlement.

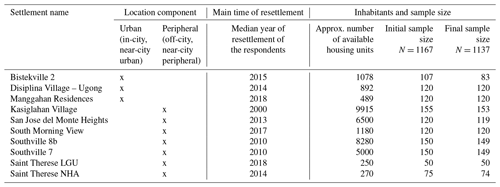

Three selected indicators briefly illustrate this observed trend in the data. The first indicator involves a comparison of safety against natural hazards. This is a central measure, considering that the reduction in hazard exposure, particularly minimizing flood risk and the clogging of waterways, served as the rational and justification for clearing the declared danger areas. The data of the household survey reveal that the major objective of improving hazard security has been largely achieved for the majority of resettled individuals. To be precise, 90.6 % or 1030 out of the 1137 respondents affirmed that their current resettlement offers greater safety against natural hazards compared to their former residence in informal settlements. A mere 1.0 % expressed that their current settlement is less secure, while 8.4 % reported a comparable level of safety to their previous situation. Furthermore, when contrasting in-city settlements with off-city settlements, the data demonstrate that in in-city settlements the rate of respondents who perceive the settlement as safer against natural hazards is marginally higher with 92.0 % compared to their off-city counterparts.

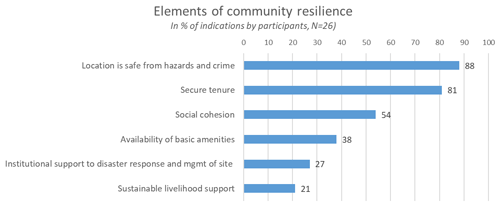

Figure 5Perceived essential elements of community resilience ranked by the frequency of the indication as relevant for FGD participants (N = 26).

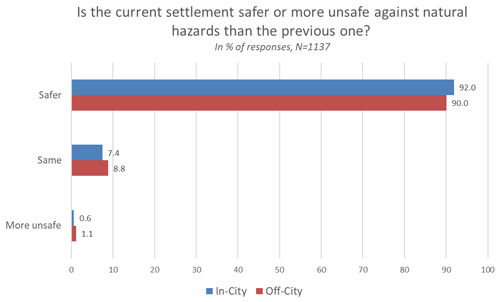

The second noteworthy indicator is the impact of the resettlement process on the quality of life for families. This indicator provides a very general yet summarizing view of perceived resettlement outcomes. An overall positive picture emerges for this indicator, with 44.2 % expressing a positive influence and 26.8 % reporting slightly positive influences, while only 7.4 % mentioned a negative influence, and 16.7 % noted a slightly negative effect. Figure 4 shows that the results slightly favour a more positive picture in in-city settlements, where a combined total of 73.7 % reported positive or slightly positive influences, compared to 69.9 % in off-city settlements.

The third indictor exemplifying the trend of the initial analysis focusses on monthly household income. Income hereby encompassed the total inflow of money from salaries, wages, self-employment, remittances, rent or other sources. The mean estimated monthly income is PHP 16 970 with a minimum of 500 and a maximum of PHP 133 500. When classified into the two settlement types, it becomes evident that in in-city settlements, the mean income is PHP 1477 higher, and the median income is PHP 1600 higher than in off-city settlements. In terms of currency conversion, this higher amount roughly equates to EUR 25 or USD 25 when fluctuations in exchange rates are not considered. Deeper analysis found that one in-city settlement (Bistekville 2) reported higher income than others with PHP 20 197.6 (median 20 000), significantly more than the settlement with the second-highest income, the far-away off-city settlement South Morning View with PHP 18 227.6 (median 15 000).

4.2 Community perception of resilient retreat

As highlighted in Sect. 3.1, the purpose of the FGDs was twofold: to validate the initial survey results and to delve deeper into how resettled communities perceive resilience to flooding given their lived experiences in coping with the impacts of the hazard. Hence, the participants were asked how they themselves think about their community resilience, hereby giving less weight to the academic discourse on resilience but more to their personal definitions and perceptions. Notably, many participants of the FGDs were already aware about the concept of resilience or at least had heard about it in the broadest sense of the community's ability to withstand shocks and fortify the quality of life. This basic understanding stems from their collaborations with local authorities or involvement in HOAs and NGOs.

The vivid discussions revealed that resilience as a collective capacity remains highly context-driven. Nevertheless, cross-cutting features suggest similar resilience-enhancing conditions mentioned in the long-established resettlement sites Kasiglahan Village and in the younger resettlement Saint Therese Housing. Based on their own understanding of resilience, as we did not further define it, the participants named and discussed various conditions associated with a resilient community.

Among these identified conditions, a safer location and better neighbourhood security tops the list of perceived essential elements of community resilience, as 88 % of the 26 participants in the FGDs claimed similar observations. Around 80 % of the participants further mentioned that possessing a legal document for their occupancy made them feel more secure and hopeful about owning their homes.

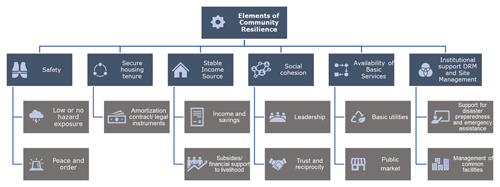

Aligning these elements with the detailed explanations given during the FGDs, six enabling factors are distilled and will subsequently serve as categories for evaluation using the quantitative data:

-

safety from flood risks due to safer location and better dwelling structure and safety from crimes;

-

secure housing due to the legal contracts that legitimize their occupancy and assurance of ownership of their homes upon completion of amortizations;

-

values of reciprocity among community members and dependable leadership;

-

relative stability of income, either through new or expanded livelihood opportunities or reduced cost of living, or expenses on basic services due to subsidies and financial assistance from the local government or other organizations;

-

availability of basic amenities, specifically water and electricity; and

-

institutional support, such as capacity building for disaster response and management, financial assistance during emergencies, and management systems for common service facilities.

4.3 Reality check: indicative levels of these enabling factors

4.3.1 Safety from flood risk and crime

Based on the insight of the initial analysis that resettlement has generally increased the safety against natural hazards, this sections delves deeper into the explicit impact of resettlement on the exposure to flooding. This is done by investigating the occurrence, the frequency and the occurred damage caused by floods in both the current resettlement sites and respondent's previous informal settlements. Although the household survey also gathered detailed information on storms, landslides and earthquakes this is not the focus of this study.

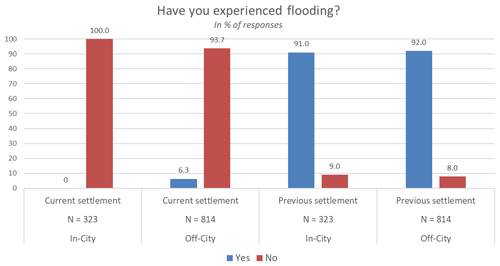

When examining the prevalence of flooding, 95.5 % of respondents report no cases of flooding in their current settlement. This marks a significant reduction in flood experience compared to the 8.3 % who did not face flooding in their previous settlement. This reduction holds true even for the younger resettlement sites, which might have a lower probability of having faced hazards, as the region experienced severe weather events in the past few years, including, for example, typhoons Ulysses in 2020 and Rolly in 2021. Upon further examination in which resettlement-site flooding incidents occurred, it was observed that all 51 cases of flooding were documented in off-city settlements, representing 6.3 % of the off-city respondents. These incidents were concentrated in particular locations, namely in Kasiglahan Village, Southville 7 and 8B, and Therese LGU. Notably, Kasiglahan Village and Southville 8B have gained a reputation for facing high exposure to flooding in certain areas of the settlements, leading to the perception of residents being “resettled from danger zones to death zones” (Ellao, 2013; Nicolas, 2021).

When respondents who experienced flooding were asked about the extent of damage resulting from these events in their current settlement, the majority reported only minor damage. Major damage, such as “collapsed walls” or “houses being washed away” were limited to Kasiglahan Village and Southville 7. In stark contrast, the situation was markedly different in their former informal settlements locations, where 68.7 % of all respondents reported damage due to flooding. Many of these cases involved severe damage and complete loss of household items or even entire dwellings. In response to questions regarding the frequency of flooding in their previous settlement, 1043 or 79.5 % of the respondents who experienced flooding reported that it occurred “several times a year”, while 8.6 % indicated that such events occurred “every few years” and 10.2 % reported that they experienced only a singular flood event.

The quantitative data align with the findings from the FGDs. Participants from Kasiglahan Village recounted their constant exposure to floods in their previous homes and shared their constant fear and anxiety every rainy season, especially during typhoons. The rising water levels of nearby tributaries forced them to evacuate regularly in their former settlement, hindering many from going to work. Since their resettlement, about 85 % of the FGD participants in Kasiglahan Village feel a sense of “peace of mind” and “at ease”, without worrying about flood water submerging their houses or being forced to take refuge in nearby schools. Residents from Saint Therese shared how most of them willingly left their old residences when they were offered to relocate to that rather remote place in Rizal Province. They mentioned the constant threat of flooding, disruption of schools, periodic evacuation from their residences to seek refuge in evacuation centres, and dependence on external support and subsidies for several days during the typhoon season.

Regarding the threat of petty crimes, the residents claimed that they feel safer, citing the “peacefulness” of their current neighbourhood with community security officers who regularly patrol the area. This observation is particularly reassuring for mothers, as it allows children and young people to mingle and play in open spaces. The neighbourhood streets are perceived safer, especially for children, thanks to the enforcement of curfews and notably reduced vehicular traffic within the resettlement area. Also this corresponds with household survey data where 78.5 % of all respondents stated that the level of security increased since the move, and 16.8 % mentioned it remained the same, while only 4.7 % reported about a decrease.

4.3.2 Secure housing

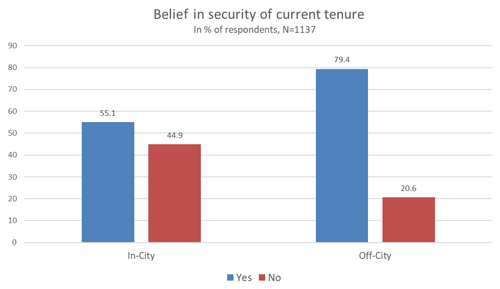

The change to a more secure housing in the wake of the resettlement is evident. A notable transition from an illegal status or, at the very least, an unclear legal status in their former settlements to a legal status is apparent, with 98.9 % of respondents indicating that they did not possess any valid documents, such as contracts or certificates, in their previous settlements. In the resettlement sites, 70.2 % now report having such documents. The availability, or lack thereof, of these documents also influences the perception of secure tenure. Whereas 99.4 % of all respondents reported that they did not have the feeling of secured tenure in the previous settlement, this number decreased to 27.5 % in the resettlement site. Conversely, 72.5 % reported feeling secure in their tenure. Nevertheless, this also implies that still over one-fourth of resettled households do not have a clarified tenure status or, at the very least, do not perceive an improvement in their status. Of particular interest is hereby that the percentage is higher in off-city settlements with 79.4 % than in in-city settlements, which report 55.1 %. Upon closer examination, this discrepancy can be attributed to a notable sense of insecurity prevalent in Disiplina Village. This is an in-city settlement with a renting scheme, where, contrary to all the other resettlement sites, people are not amortizing the house or apartment to which they were resettled. Obviously, a significant number of residents in this settlement do not perceive renting as providing long-term secured tenure.

The FGDs can provide details on improvement in secure housing but also on why still many do not perceive security. When asked about the security of the housing, 21 participants agreed that becoming a beneficiary of the housing programme and paying monthly amortization increased their confidence in owning their units in the future: “We can live decently and peacefully because we do not have to worry about flooding in the house and getting evicted or our houses getting demolished”. Others stated that they can now better focus on their work and meet their family's other needs. However, the security of tenure is primarily tied to the capacity to pay the monthly amortization or the rent. Accordingly, the participants from Kasiglahan Village came to the shared opinion that the tenure situation remains a source of fear, not providing real housing security. It is reported that many resettled people in the site either cannot or do not pay the monthly amortization, creating fear of potential eviction. In this situation, it does not help that they received the so-called entry pass, stating the right to live in the given house but not constituting a legal document for ownership.

4.3.3 Improved social cohesion

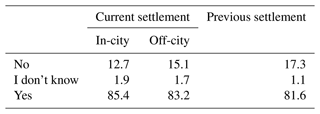

The social relations and networks within the settlement or among the families appear to be well-established in resettlement sites, even slightly surpassing the levels observed in the previous settlements. This is evident when examining the data related to seeking help from neighbours as illustrated in Table 2.

Table 2Responses (in %) to the question: “Would you feel comfortable to ask your neighbours for help (e.g. to mind children or support repairing the house), N = 1137.

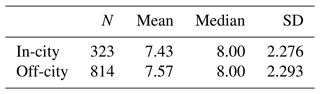

Table 3How do you rate the solidarity between people (sense of belonging or togetherness) in the current settlement? Rating from 0–10 (10 highest possible), N = 1137.

One reason might be that many have family or very close friends in the same settlement, as mentioned by 82.5 % of all respondents. This is only slightly lower than in the original settlement, where 87.5 % mentioned this circumstance. Notably, the percentage is higher for off-city settlements at 85.3 % compared to in in-city settlements at 75.5 %. This disparity may stem from the limited spaces available in in-city settlements. Another contributing factor is the involvement in self-help and lending groups, as well as in people's groups or associations such HOAs. Specifically, 83.0 % reported awareness of the existence of self-help groups and lending systems within the resettlement site, which is slightly higher than the 80.3 % in the previous settlement. When asked if they are organized in people's groups or an association, 69.3 % responded “yes”, a significantly higher percentage than in the previous settlement where only 29.6 % were organized. The organization rate is higher in in-city settlements, standing at 86.7 % compared to 62.4 % in off-city settlements, indicating a strong level of organization within the resettlement sites. Overall, when respondents were asked to rate the solidarity between people in terms of belonging and togetherness in the new settlement, the result was a mean of 7.53 and a median of 8 on a scale ranging from 0 to 10, with 10 as the highest value. The value was slightly higher in off-city settlements, with a mean of 7.57.

In the FGDs, all participants affirmed a change in community relations after the resettlement, underscoring their learning from forming a unity and getting organized. This strong form of organization seems to be attributed to the hardship experienced during the resettlement process, where everyone found themselves in a similar situation of starting anew. To overcome this hardship, one opportunity, maybe the only real opportunity, has been to come together, organize each other, help out and potentially also articulate shared interests.

Further, respondents mentioned benefits from having a trustworthy leader and members' cooperation, helping to unify in meeting their basic needs and safeguarding their community from hazards. In Kasiglahan Village, participants shared how their local leader encouraged them to share the cost of a temporary power supply for their houses during the early phase of their resettlement: “Each household in Phase 1-B regularly contributed five pesos for petrol to run the association's generator set, which was our temporary source of electricity for 3 months, while our (association) officers negotiated with the NHA to install permanent supply lines”. This unity among members empowered the association to advocate for support to install other utilities and amenities, such as water supply and building a local church within the settlement.

In Saint Therese, participants shared that there was no problem among their fellow relocates but also shared their initial challenges of being rejected by the host community when some barangay residents rejected them upon their arrival: “Some people used to disturb our site. They threw stones at us or our houses and stole personal belongings like slippers”. Through collaborative efforts between their association and barangay officers, several assemblies and orientations were held to introduce the relocated people to the initial barangay residents. Over time, the newcomers began joining other community activities, fostering relations with the locals.

4.3.4 Income stability

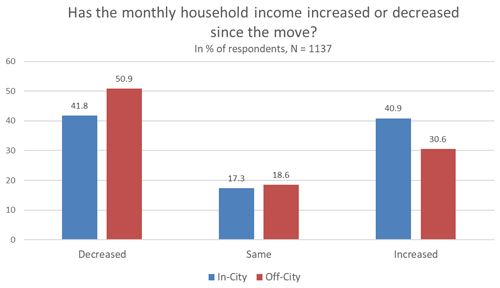

The household data document an overall reduction in financial capital. The respondents indicated that their income has predominantly decreased since their resettlement, with 48.3 % experiencing a decrease, while 18.2 % noted that it remained unchanged, and 33.5 % reported an increase in their income. Notably, the decrease in income is significantly higher in off-city settlements, where 50.9 % reported a decrease, compared to 41.8 % in in-city settlements.

The initial analysis of Sect. 4.1 already elaborated that the estimated monthly household income is PHP 16 970 with a higher mean income of PHP 1477 in in-city settlements. When asked if they are able to save money, 71.0 % of all respondents answered “no”. This percentage is lower when respondents were asked if they were able to save money before their resettlement, with 53.2 % responding “no”. Furthermore, the ability to safe money now is higher in in-city settlements, where 38.7 % claimed to be able to save, compared to 25.2 % in the off-city counterparts.

The qualitative data from the FGDs show a more nuanced view on the financial situation. A total of 17 participants claimed in the discussion that their livelihood slightly improved as income sources became more stable, especially before the COVID-19 pandemic. They explained that this situation did not manifest immediately after moving to the resettlement site. They needed time to adjust and find work. Over the years, most found income opportunities within the site and nearby areas. Some reported diversifying their income sources, providing tricycle service or water delivery. Several residents opened small retail shops, ran home-based food businesses, offered their neighbours housekeeping services, or worked in the local market. Others secured new employment in the nearby areas, leveraging their trade skills for more stable income. However, many also report about people still commuting to urban areas of Metro Manila for work. Often these are husbands or young men, who work for example in the construction sector or as security guards, sometimes only returning to the settlement on weekends. Overall, the FGDs document a general feeling that the incomes have not substantially increased from previous earnings, but for many, the costs of essential services are lower, allowing them to have higher disposable income to cover housing and education needs.

4.3.5 Availability of basic services

The access to the analysed basic services – water, electricity and sewage treatment – has improved as a result of resettlement. Looking at water supply, 97.8 % now have access to piped water, marking a notably increase from 64.6 % in their former settlement. Access to electricity stands at 99.2 %, with only isolated cases lacking due to various reasons, such as unpaid bills or technical issues. But also in their previous settlements, the access was good, with 93.8 % connected to service providers and 5 % using so-called jumper connections. In both services, there are marginal differences between resettlement types, with slightly better access reported in in-city settlements (electricity 100 % to 98.9 %; water 99.7 % to 97.1 %). However, access to sewage systems presents a different scenario. Two systems are in use: household septic tanks and connection to a public sewage system. In-city settlements are primarily connected to a public sewage system, while in off-city settlements, the majority relies on septic tanks. In this service category, a substantial improvement is noticeable. In their previous settlements, 41.3 % of respondents reported a lack of sewage system, leading to the discharge of sewage directly to the river or waterbodies.

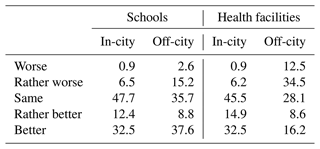

Table 4Responses (in %) to the task: “Rate the accessibility of human capital facilities now in comparison to your previous settlement”, N = 1137.

When regarding the accessibility of education and health facilities, the data indicate mostly similar or better access to schools than before the resettlement, whereas for health facilities, the access is reported similar or rather worse. Comparing the two types of settlements, it is evident that the change in in-city settlements is not that significant, with 47.7 % reporting similar access to schools and 45.5 % for health facilities. However, in off-city settlements, there is a more noticeable change, showing increased access to schools and a tendency towards relatively reduced access to health facilities.

The insights from the FGD in Kasiglahan Village suggest that the positive shift in the accessibility of basic amenities documented in the quantitative data only materialized over time and by constant claims. Participants reported that more than 20 years ago, when they first arrived at the settlement, basic services were inadequately provided or even absent: “In the year 2000, we did not have basic services like school, electricity, water, and church. Water supply came from Pasig City and was delivered to our community at dawn”. The situation only improved through constant advocacy and claims by HOAs and other civil society organizations. In the younger settlement of Saint Therese such deficiencies in service provision are not reported by the FGD participants. This indicates potential improvements in the resettlement process, i.e. the implementation of resettlement guidelines and procedures. However, due to the small size of the settlement with only around 250 housing units, respondents noted a lack of public amenities, such as a small public market and a chapel.

4.3.6 Institutional support to disaster management and of common service facilities

The survey data provide limited insights into the enabling factor of institutional support. Some indicators may partially illuminate this aspect but not to overall satisfaction. For instance, the questions of whether the resettled individuals received compensation for leaving their previous settlement is somewhat linked to institutional support. In this regard, 64.3 % of respondents reported receiving compensation payments, with a median value of PHP 18 000. This payment serves as initial support to assist in staring anew, often accompanied by food packages and groceries. Herein, the resettlement of informal settlers, who mostly lack legal documents for their dwellings, is fundamentally different from retreat in formal settings with buy-out programmes. Another relevant indicator is the provision of livelihood support in the form of training activities. In this context, only 2.9 % reported that they were offered livelihood training after the move. Additionally, when asked about the effectiveness of estate management, which exists in all settlements, 75.3 % of respondents reported that it is working fine.

For a more nuanced understanding of this enabling factor, the FGD results, particularly those from Kasiglahan Village, may provide richer insights compared to the quantitative data. These FGD results suggest that the relationship with institutions is not well-established and comes with challenges. This is evident from the absence of basic services in the early years of the settlements and grew alongside the recurring flooding in some parts of the settlement. The residents of Kasiglahan Village were able to address their issues and needs only through the formation of associations and unions among themselves, demonstrating the importance of bonding social capital. Moreover, the persistent fear of eviction when residents struggle with payments reinforces the view that institutional support is far from perfect.

The sequential multi-method research design utilized in this study worked well in addressing the research interest. It facilitated the integration of a comprehensive quantitative dataset with qualitative measures to validate and delve deeper into resettlement practices. The approach identified community-defined resilience elements, illustrated in Fig. 9, that serve as enabling factors for resilient retreat. These elements, at the very least, constitute the minimum preconditions that should be addressed or satisfied by any resettlement initiative. They hold significance as they were not defined as an outcome of the literature review or conceptual work of the research team but by statements of residents when they reflected on community resilience.

The assessment of these enabling factors across the 10 resettlement sites revealed valuable insights, encapsulated in two overarching findings. Firstly, there is a prevalence of reported improvements in the enabling factors compared to negative trends. That means planned resettlement seems to be more positive than anticipated. Improvements due to resettlement were particularly related to the reduction in hazard exposure and a higher security from crime. Also basic conditions that may help people to get out of chronic poverty, such as secure land tenure and the access to basic services, improved due to resettlement in the sites assessed. Also the social cohesion in the new site was positively evaluated. From these factors, security from hazard impacts and social cohesion deserve particular attention. Risk reduction due to a higher security from hazard impacts was primarily achieved by reducing hazard exposure and improved building material (higher robustness). The reduction in hazard exposure was measured through the three indicators hazard occurrence, frequency and occurred damage, recognizing that the occurred damage can already tend towards risk. It is likely that these indicators cannot completely guarantee hazard security and might not adequately account for future risk associated with further climate change impacting on hazards trends. However, resettlement addressed the most urgent need for exposure reduction. This was crucial for the respondents who faced frequent flooding and damage before their resettlement. Accordingly, the primary objective for the actual resettlement from danger areas could be achieved for most settlements and for most resettled individuals. This implies a substantial improvement in the precarious living situations of those resettled. However, in resettlement sites where flooding was reported in certain areas, additional measures such as flood protection measures or, in extreme cases, resettlement from highly exposed zones may be necessary. The other emphasis is on the strengthened social cohesion as this is countering the risk of marginalization and loss of social structures frequently highlighted in the literature on resettlement and displacement. This strengthening can be attributed to the fact that most resettled people did not resettle alone and that the resettlement process itself served as a catalyst for unity and the formation of associations.

Besides the positive effects on enabling factors, there are negative and inconclusive outcomes for the assessment categories stable income source and institutional support. Concerning monthly income, the data predominantly indicate a decrease. This implies subsequent challenges in other enabling factors, such as housing security. When the income source is unstable or insufficient, there are not enough financial resources to make the payments for amortization, having the effect that the culture of dependency from the NHA cannot be overcome and, ultimately, eviction from the resettlement site remains a potential threat. The factor institutional support, on the other hand, lacks sufficient data. However, insights from the vivid debates of the FGDs suggest ample room for improvement, ensuring that retreat is not only about providing houses and financial schemes for amortizing these houses.

Based on the obtained data in the selected case study sites, the second major insight of the assessment is that post-resettlement conditions only slightly vary between the two resettlement types. The initial analysis (Sect. 4.1) gave hindsight, and the detailed reality check validates this. Accordingly, the results are inconclusive in illustrating that in-city resettlement produces significantly better conditions for the enabling factors than the off-city modality. On one hand, there are factors where the in-city settlements perform better. Notably, hazard exposure is lower in in-city settlements compared to the off-city category, mainly due to individual off-city settlements that are affected by flooding and meanwhile known specifically for high exposure in some parts of the settlements. Additionally, the analysed income indicators show mainly slightly better outcomes in urban settings. On the other hand, some factors and individual indicators are assessed slightly higher in off-city settlements. This is particularly the case for social cohesion. However the picture is less clear for housing security, which largely depends on the different housing types and tenure schemes present in the settlements. In-city settlements predominantly consist of multi-storey medium-rise buildings, while off-city settlements are uniformly built with row houses on small lots. It turns out that the renting scheme in the in-city settlement Disiplina Village is perceived as providing less secure housing tenure leading to an overall feeling of a less secure tenure in the in-city category.

Hence, the results revealed no discernible pattern of improvement observed in either settlement. This suggests that the location, in the sense of an urban or rather rural setting, may not be a compelling factor for resilience and improved well-being if the same policies and processes remain in force. This observation is relevant and contradicts the dichotomy of the ongoing discussion on off-city versus in-city resettlement. Consequently, the finding that in-city resettlement, in the current practice, might not necessarily be the better option for resettled people needs further argument in Sect. 6 on political implications.

The need for adaptation and risk reduction to extreme events like storms and floods as well as to creeping changes such as sea level rise is evident for highly exposed urban coastal areas worldwide. Managed retreat is already being applied, though not always explicitly labelled as retreat, but it is a reality and thus must be part of the adaptation portfolio as a strategic planning tool. The study identified enabling factors that not only provide a framework for assessing the success of resettlement or retreat activities, recognizing the complexity of defining success in such contexts, but also serve as essential criteria for project implementation. By prioritizing these conditions, resettlement processes can harness the resilience of urban poor communities. These enabling factors may complement more classical analytical models, such as Michael Cernea's impoverishment risks and reconstruction (IRR) model (Cernea, 1997).

In translating these findings into practical recommendations, it becomes clear that not only adaptation requires a portfolio of measures but that retreat itself must consist of a diverse portfolio of options. Contrary to expectations, this study indicates that the location of the resettlement site, whether in a more urban or rural setting, does not significantly determine the success or failure of projects. Accordingly, the dichotomous thinking with the preferred in-city scheme versus the long time predominant off-city scheme is obstructive. Instead, a nuanced approach is necessary, offering programmes suitable to the needs of different target groups. For instance, well-planned and managed off-city resettlement may be favourable for some households, potentially for larger ones, while for others a non-extendable 24 m2 apartment in an in-city condominium building may be suitable.

In contrast to the new agenda of fast and large-scale in-city retreat, offering a one-size-fits-all solution, there is pressing need for flexible financing schemes and diverse housing and settlement typologies. While existing mechanisms and tools like People's Plan approaches and community mortgage programmes offer potential solutions, their implementation often faces bureaucratic hurdles and lacks prioritization from stakeholder. This is very exhausting for the involved communities, who are in parallel managing their precarious livelihood system and coping with shocks such as the coronavirus pandemic and natural hazards. Introducing additional tools and mechanisms such as community involvement in construction works and sweat equity agreements or more incremental approaches could enhance flexibility and effectiveness.

It is crucial for stakeholders to recognize that retreat is a complex process requiring time and alignment with the capabilities of the target group – in the Philippines mainly informal and low-income households. Accordingly resettlement projects are challenged by a highly dynamic urban development with skyrocketing land prices. This study highlighted that many resettled individuals express concerns about eviction due to difficulties in meeting the monthly amortization payments. This indicates that the proposed in-city condominium apartments will be financially not attainable by most informal settlers, highlighting that the problem with low-income housing is less housing than low income. Instead of introducing a far too ambitious one-size-fits-all approach, the government must play a proactive role in land management and provide financial support to local authorities for urban development and resettlement.

Ultimately, a nuanced policy formulation is essential, including an incorporation of an improved risk understanding. Establishing a new risk-informed danger area legislation could provide a direct entry point for nuanced retreat practices. Such legislation should not only define transparent criteria and clear methods for identifying danger areas but also outlining instruments and standards for their management and planning. Rather than hastily resettling ISFs to standardized high-rise in-city structures, a risk-informed framework should prioritize protection goals and offer a portfolio of flexible solutions, including retreat where necessary.

Due to privacy issues the questionnaire data are not publicly accessible, but they can be provided through a request to the corresponding author.

Conceptualization: HL, CMCC, EL; methodology and software: HL, EL; formal analysis: HL, CMCC, EL, SI; writing (original draft): HL, EL, SI; writing (review and editing): HL, CMCC, EL, JB; project administration: HL, CMCC, JB. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the paper.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors.

This article is part of the special issue “Strengthening climate-resilient development through adaptation, disaster risk reduction, and reconstruction after extreme events”. It is not associated with a conference.

This paper presents findings from the research project titled “Linking Disaster Risk Governance and Land Use Planning: the Case of Informal Settlers in Hazard Prone Areas in the Philippines (LIRLAP)”. This project is funded by the German Federal Ministry for Education and Research (BMBF) under the funding programme “Sustainable Development of Urban Regions”, grant no. 01LE1906C1.

This research has been supported by the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (grant no. 01LE1906C1).

This open-access publication was funded by the University of Stuttgart.

This paper was edited by Viktor Rözer and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Adams, H.: Why populations persist: mobility, place attachment and climate change, Popul. Environ., 37, 429–448, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11111-015-0246-3, 2016.

Ajibade, I.: Planned retreat in Global South megacities: disentangling policy, practice, and environmental justice, Climatic Change, 157, 299–317, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-019-02535-1, 2019.

Ajibade, I., Sullivan, M., Lower, C., Yarina, L., and Reilly, A.: Are managed retreat programs successful and just? A global mapping of success typologies, justice dimensions, and trade-offs, Global Environ. Chang., 76, 102576, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2022.102576, 2022.

Alvarez, M. K.: Benevolent Evictions and Cooperative Housing Models in Post-Ondoy Manila, RHJ, 1, 49–68, https://doi.org/10.54825/JEJO3330, 2019.

Arnall, A.: Resettlement as climate change adaptation: what can be learned from state-led relocation in rural Africa and Asia?, Clim. Dev., 11, 253–263, https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2018.1442799, 2019.

Ballesteros, M. M.: Rethinking Institutional Reforms in the Philippine Housing Sector, PIDS Discussion Paper Series, Philippine Institute for Development Studies, Makati City, Philippines, 2002.

Ballesteros, M. M.: Evaluating the Benefits and Costs of Resettlement Projects: A Case Study in the Philippines, in: Evaluation for Agenda 2030: Providing Evidence on Progress and Sustainability, edited by: van den Berg, R. D., Naidoo, I., and Tamondong, S. D., Exeter, 257–271, ISBN 978-1-9999329-1-6, 2017.

Ballesteros, M. M. and Egana, J. V.: Efficiency and Effectiveness Review of the National Housing Authority (NHA) Resettlement Program, PIDS Discussion Paper Series, Philippine Institute for Development Studies, Makati City, Philippines, 2013.

Birkmann, J. and Lauer, H.: Climate change: Mitigation and adaptation, in: Routledge handbook of environmental hazards and society, edited by: Penning-Rowsell, E. C. and McGee, T. K., Routledge, New York, NY, https://doi.org/10.4324/9780367854584-13, 2022.

Black, R., Adger, W. N., Arnell, N. W., Dercon, S., Geddes, A., and Thomas, D.: The effect of environmental change on human migration, Global Environ. Chang., 21, S3-S11, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.10.001, 2011.

Cao, A., Esteban, M., Valenzuela, V. P. B., Onuki, M., Takagi, H., Thao, N. D., and Tsuchiya, N.: Future of Asian Deltaic Megacities under sea level rise and land subsidence: current adaptation pathways for Tokyo, Jakarta, Manila, and Ho Chi Minh City, Curr. Opin. Env. Sust., 50, 87–97, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2021.02.010, 2021.

Carey, J.: Core Concept: Managed retreat increasingly seen as necessary in response to climate change's fury, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 117, 13182–13185, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2008198117, 2020.

Cernea, M.: The risks and reconstruction model for resettling displaced populations, World Dev., 25, 1569–1587, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(97)00054-5, 1997.

Dannenberg, A. L., Frumkin, H., Hess, J. J., and Ebi, K. L.: Managed retreat as a strategy for climate change adaptation in small communities: public health implications, Climatic Change, 153, 1–14, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-019-02382-0, 2019.

de Guzman, J. S.: Is the `Pabahay' target of one million houses a year realistic?, INQUIRER.net, 17 March 2023, https://opinion.inquirer.net/161765/is-the-pabahay-target-of-one-million-houses-a-year-realistic (last access: 2 November 2023), 2023.

de Sherbinin, A., Castro, M., Gemenne, F., Cernea, M. M., Adamo, S., Fearnside, P. M., Krieger, G., Lahmani, S., Oliver-Smith, A., Pankhurst, A., Scudder, T., Singer, B., Tan, Y., Wannier, G., Boncour, P., Ehrhart, C., Hugo, G., Pandey, B., and Shi, G.: Climate change. Preparing for resettlement associated with climate change, Science, 334, 456–457, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1208821, 2011.

De Wet, C. J.: Introducing the issues, in: Development-induced displacement: Problems, policies and people, edited by: De Wet, C. J., Berghahn, New York, NY, 1–12, https://doi.org/10.3167/9781845450953, 2006.

Delos Reyes, M. R. and Francisco, A. N.: Building Sustainable and Disaster Resilient Informal Settlement Communities, Public Policy, 2014–2015, 173–200, 2015.

Doberstein, B., Tadgell, A., and Rutledge, A.: Managed retreat for climate change adaptation in coastal megacities: A comparison of policy and practice in Manila and Vancouver, J. Environ. Manage., 253, 109753, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.109753, 2020.

Du, J. and Greiving, S.: Reclaiming On-Site Upgrading as a Viable Resilience Strategy-Viabilities and Scenarios through the Lens of Disaster-Prone Informal Settlements in Metro Manila, Sustainability, 12, 10600, https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410600, 2020.

Ellao, J. A. J.: From danger zones to a death zone, Bulatlat, 22 October 2013, Bulatlat, https://www.bulatlat.com/2013/10/22/from-danger-zones-to-a-death-zone/ (last access: 28 November 2023), 2013.

Ferris, E. and Weerasinghe, S.: Promoting Human Security: Planned Relocation as a Protection Tool in a Time of Climate Change, Journal on Migration and Human Security, 8, 134–149, https://doi.org/10.1177/2331502420909305, 2020.

Galuszka, J.: Co-Production as a Driver of Urban Governance Transformation? The Case of the Oplan LIKAS Programme in Metro Manila, Philippines, Planning Theory & Practice, 20, 395–419, https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2019.1624811, 2019.

Galuszka, J.: Civil society and public sector cooperation: Case of Oplan LIKAS, Policy Notes, Philippine Institue for Development Studies (PIDS), Quezon City, Philippines, 8 pp., https://www.pids.gov.ph/publication/policy-notes/civil-society-and-public-sector-cooperation-case-of-oplan-likas (last access: 1 July 2024), 2018.

Galuszka, J.: Adapting to informality: multistory housing driven by a co-productive process and the People's Plans in Metro Manila, Philippines, Int. Dev. Plann. Rev., 1–29, https://doi.org/10.14279/DEPOSITONCE-10072, 2020.

Glavovic, B. C., Dawson, R., Chow, W., Garschagen, M., Haasnoot, M., Singh, C., and Thomas, A.: Cities and Settlements by the Sea, in: Climate Change 2022 – Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability, edited by: IPCC, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, New York, NY, USA, 2163–2194, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009325844.019, 2023.

Greiving, S., Du, J., and Puntub, W.: Managed Retreat — A Strategy for the Mitigation of Disaster Risks with International and Comparative Perspectives, J. Extr. Even., 05, 1–35, https://doi.org/10.1142/S2345737618500112, 2018.

Haasnoot, M., Lawrence, J., and Magnan, A. K.: Pathways to coastal retreat, Science, 372, 1287–1290, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abi6594, 2021.

Hauer, M. E., Fussell, E., Mueller, V., Burkett, M., Call, M., Abel, K., McLeman, R., and Wrathall, D.: Sea-level rise and human migration, Nat. Rev. Earth Environ., 1, 28–39, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43017-019-0002-9, 2020.

Hino, M., Field, C. B., and Mach, K. J.: Managed retreat as a response to natural hazard risk, Nat. Clim. Change, 7, 364–370, https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate3252, 2017.

Hoang, T. and Noy, I.: Wellbeing after a managed retreat: Observations from a large New Zealand program, Int. J. Disast. Risk Re., 48, 101589, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101589, 2020.

Horton, R. M., Sherbinin, A. de, Wrathall, D., and Oppenheimer, M.: Assessing human habitability and migration, Science, 372, 1279–1283, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abi8603, 2021.

IPCC (Ed.): Climate Change 2014: Impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability: Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, volumes 〈1–2〉, 2014.

Jensen, S., Hapal, K., and Quijano, S.: Reconfiguring Manila: Displacement, Resettlement, and the Productivity of Urban Divides, Urban Forum, 31, 389–407, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12132-020-09399-0, 2020a.

Jensen, S., Hapal, K., and Quijano, S.: Reconfiguring Manila: Displacement, Resettlement, and the Productivity of Urban Divides, Springer, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12132-020-09399-0#citeas (last access: 6 November 2023), 2020b.

Jevrejeva, S., Jackson, L. P., Riva, R. E. M., Grinsted, A., and Moore, J. C.: Coastal sea level rise with warming above 2 °C, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 113, 13342–13347, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1605312113, 2016.

Katigbak, T. K.: How to build one million houses a year, Manila Bulletin, 2 November 2023, https://mb.com.ph/2023/02/20/how-to-build-one-million-houses-a-year/ (last access: 2 November 2023), 2023.

Kulp, S. A. and Strauss, B. H.: New elevation data triple estimates of global vulnerability to sea-level rise and coastal flooding, Nat. Commun., 10, 4844, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-12808-z, 2019.

Lapidez, J. P., Tablazon, J., Dasallas, L., Gonzalo, L. A., Cabacaba, K. M., Ramos, M. M. A., Suarez, J. K., Santiago, J., Lagmay, A. M. F., and Malano, V.: Identification of storm surge vulnerable areas in the Philippines through the simulation of Typhoon Haiyan-induced storm surge levels over historical storm tracks, Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci., 15, 1473–1481, https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-15-1473-2015, 2015.