the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

How to communicate and educate more effectively on natural risk issues to improve disaster risk management through serious games

Mercedes Vázquez-Vílchez

Rocío Carmona-Molero

Tania Ouariachi-Peralta

This study explores the potential of serious games for improving disaster risk management. The research employs a qualitative approach, combining content analysis of serious games (six digital games – three mobile apps and three online games) with an online survey of experts featuring open-ended questions. The results show that only the online games aligned with the informative narrative tone indicated by the experts, while the gameplay of the mobile apps focused more on interaction. Such interaction could enhance the playful aspect of the game and thus increase the desire to play; however, the educational aspect of online games is much higher, despite a few examples having inadequate representation of multiculturalism, diversity, and gender. This paper provides a list of recommended features for disaster risk management games, which we have categorized into three dimensions: (a) characters; (b) information and message tone; and (c) narrative dynamics, reward systems, and feedback. The results of the study may be of considerable help to teachers and game designers in improving citizens' knowledge of disaster risk management.

- Article

(1947 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(699 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Today's scientific and technological advances allow us to anticipate natural hazards and take early action, both at governmental and civilian levels. However, the occurrence of devastating disasters in countries of varied economic and cultural scale shows that these technological and scientific advances in disaster risk management (DRM) do not necessarily correspond to their correct implementation. Recent examples of major disasters include the 2024 floods in Spain; the 2021 floods that affected Germany, Belgium, and the Netherlands; and the devastating earthquake that struck Türkiye and Syria in 2023, resulting in significant loss of life and economic damage. Therefore, there is a huge gap between scientific-technological valuations and their practices and implementation, and this communication is a critical factor in DRM (Solinska-Nowak et al., 2018; Weyrich et al., 2021).

The dynamics of conflict resolution following natural hazards are based on centralized processes in which decision-making is dominated to governments, scientists, and experts (Clerveaux et al., 2008; Tanwattana and Toyoda, 2018), which minimize the participation of affected communities. In extreme cases, these decisions may even be made without considering the local cultural, social, or economic norms of the affected area. In this context, in the 21st century, there has been a growing interest in changing such hierarchical decision-making and developing more participatory strategies involving communities (Yamori, 2007; Suarez et al., 2014; Tanwattana and Toyoda, 2018). From this perspective, society is not understood as requiring only one monolithic solution proposed by stakeholders such as scientists or politicians, but as one where dialogue is possible and diverse viable answers coexist (Yamori, 2011). Some authors suggest mutual learning to promote the democratization of decisions, which combines diverse learning methodologies, such as adaptive management, experiential learning, and transformative learning (e.g. Lavell et al., 2012). Some important approaches in adaptive management incorporate the use of knowledge co-production, where scientists, politicians, and other stakeholders work to exchange, create, and implement knowledge (Van Kerkhoff and Lebel, 2006). In this sense, participatory mapping, workshops, and hackathons have been highlighted as possible options (e.g. Sullivan-Wiley et al., 2019; Trejo-Rangel et al., 2023; Macholl et al., 2024). These approaches integrate local knowledge of natural hazards into vulnerability evaluation, highlighting diverse vulnerabilities to natural hazards that are co-produced at local scales (Sullivan-Wiley et al., 2019). Experiential (Kolb, 2015) and transformative (Mezirow, 1995) learning underscore the importance of action oriented towards problem-solving and learning-by-doing and how these processes originate reflective thinking, theory generation, and knowledge application, enabling behaviour change for adaptation to natural hazards (Sharpe, 2016; Lavell et al., 2012).

Following this approach, which hypothesizes that acquiring knowledge about natural hazards enables citizens to make decisions and implement prevention measures, there is recognition of the need for active teaching methodologies, such as serious games, which may serve as a participatory and supportive tool for understanding the essential aspects of natural hazards (e.g. Solinska-Nowak et al., 2018; Tanwattana and Toyoda, 2018; Tsai et al., 2020; Schueller et al., 2020; Teague et al., 2021; Altan et al., 2022; Villagra et al., 2023). Serious games allow users to visualize and explore phenomena that would otherwise be challenging to experience by enhancing player immersion and allowing them to learn about the consequences of their actions at different points in time during a natural hazard (Solinska-Nowak et al., 2018; Heinzlef et al., 2024). In this way, serious games encourage experiential and transformative learning, as they aim to reproduce a context as close to reality as possible to facilitate behaviour change among players to enhance adaptation and resilience to natural hazards (Villagra et al., 2023). The effectiveness of learning through serious games is enhanced by the immediate feedback and the emotional and sensorial experiences they provide, essential for learning to mitigate the effects of natural hazards (Solinska-Nowak et al., 2018; Heinzlef et al., 2024). However, while serious games can provide useful evidence on how people conceive disasters, the representation of catastrophes within popular culture is poorly understood (Gampell and Gaillard, 2016; Safran et al., 2024). Some authors relate the characteristics of several disaster games to the disaster risk reduction framework (mitigation, preparedness, and recovery), highlighting the need for further research into how game characteristics (mechanics, dynamics, narrative, and content) and player skills, motivations, and social interactions contribute to improving decision-making in the area of disaster risk reduction (DRR) (Gampell and Gaillard, 2016; Safran et al., 2024). Few works address the influence of video games on players' tendency to prepare for natural hazards (Tanes and Cho, 2013; Tanes, 2017; Safran et al., 2024). Attention is drawn to the lack of scientific evidence on the potential of serious games as well as the challenges remaining for the development of more detailed studies to test and demonstrate the effectiveness of serious games for DRM education (Weyrich et al., 2021; Safran et al., 2024).

This paper aims to explore the potential of serious games for improving DRM. The main research question it raises is how can we improve education and communication about natural hazards through serious games? To this end, the following research sub-questions are posed: (a) How do serious games communicate and educate users on issues related to natural hazards? and (b) What are the educational and communicative elements or characteristics that serious games should have to improve DRM? The research method includes a qualitative research approach, incorporating content analysis of selected serious games on DRM, and an online survey with open-ended questions for experts.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: an overview of serious games as tools for learning and change, especially for DRM (Sect. 2); a description of the qualitative methodological approach used (Sect. 3); a presentation of the qualitative content analysis of serious games and the results of the open-ended online survey (Sect. 4); and finally, a discussion of the results (Sect. 5) and main conclusions, including the limitations of this study and recommendations for future works (Sect. 6).

2.1 Serious games for learning and change

A large body of research supports the idea that active learning can improve learning performance more than traditional learning strategies, with gamification being one of the more representative examples (e.g. Tolks et al., 2024). Gamification refers to the use of game design elements in non-game contexts, in order to enhance learning and certain behaviours (e.g. Ramírez-Cogollor, 2014). Games awaken, engage and motivate, provide social and civic skills, and promote problem-solving capabilities (e.g. Liao et al., 2023; Safran et al., 2024). Today, educational platforms are increasingly incorporating game elements (e.g. points, badges, difficulty levels, and leaderboards) so as to measure and encourage learning outcomes by adding scores and feedback (Hellín et al., 2023).

Serious games are those that aim not only to entertain, but also to teach, convey ideas and values, and influence the thoughts and actions of players in real-life contexts (e.g. Frasca, 2007; Bylieva et al., 2019; Sáiz-Manzanares et al., 2021). The terms “serious games” and “game-based learning” are frequently used synonymously (Corti, 2006), although serious games are often created with the broader aims of training and facilitating behaviour change in various fields, including business, healthcare, NGOs, and education (Sawyer and Smith, 2008). Serious games are also referred to as “change games” (Bogost, 2007; Courbet et al., 2016) and “social impact games” (Cremers et al., 2015).

Serious games have experienced a rapid increase over the last decade, with extensive research providing empirical evidence of cognitive benefits (Vogel et al., 2006; Bellotti et al., 2013), as well as impacts on affective and motivational outcomes (Connolly et al., 2012; Wilson et al., 2009; Pineda-Martínez et al., 2023). Serious games allow users to visualize and explore phenomena, which would otherwise be very difficult to experience, and see the consequences of their actions at different times (Wiek and Iwaniec, 2014). One of the significant benefits of learning through serious games is the immediate feedback they provide. These kinds of games allow active learning through problem solving, where students focus solely on their learning (Medina, 2012). In addition, serious games favour personal autonomy and social and cultural engagement (Magnuszewski et al., 2018).

A special case is that of serious games based on computer technologies, which have experienced a rapid increase in the last decade, increasingly replacing traditional games. Computer games take advantage of young people's interest in social networks and video or online games; can cover diverse learning objectives and multiple fields; and target different age groups (Mouaheb et al., 2012). Playing computer games is associated with a range of cognitive, affective, behavioural and motivational impacts and outcomes, the most common of these being knowledge acquisition and content comprehension (Connolly et al., 2012). Considering their characteristics, there is a wide variety of genres and formats, from simulations, which replicate aspects of real or fictional realities, and adventures, in which users solve challenges by interacting with people or the environment in a non-confrontational manner (Lamb et al., 2018; de Freitas, 2018; Heintz and Law, 2015, 2018).

2.2 Serious games for disaster risk management

Most disaster-related serious games involve social simulations and role-playing (Solinska-Nowak et al., 2018; Cremers et al., 2015). These types of games are intended for a large number of players, from different contexts, providing them with opportunities for face-to-face discussion and negotiation about a given problem. Players have the opportunity to share different values and perspectives and engage with stakeholders with conflicting interests to cooperate towards a common goal (Akhtar et al., 2020).

Floods (e.g. Teague et al., 2021; Tsai et al., 2020; Gordon and Yiannakoulias, 2020), earthquakes (e.g. Safran et al., 2024; Feng et al., 2020; Whaley, 2019), and droughts (e.g. Poděbradská et al., 2020; Wang and Davies, 2015) are the most common subjects of natural hazard games (Solinska-Nowak et al., 2018). This is in line with occurrence statistics. Data from the Emergency Events Database (EM-DAT, CRED) shows that in 2023, floods were the most common natural hazards globally (163 events, 44 %), followed by storms (139 events, 37 %) and earthquakes (30 events, 8 %) (ADRC, 2023). On the other hand, the three dominant themes correspond to those causing the highest number of deaths (IFRC, 2020), and it is reasonable that they are the most represented in serious games.

Most serious games aim to strengthen players' preparation capacity for natural hazards (Solinska-Nowak et al., 2018). These games provide instructions through appropriate activities on buildings, preparing emergency kits, stockpiling equipment and supplies, and recognizing the first signs of disasters (e.g. Tanwattana and Toyoda, 2018; Teague et al., 2021; Mossoux et al., 2016). In contrast, there are fewer games that focus on the post-disaster phase, including evacuation management (e.g. Feng et al., 2020) or how to save people (e.g. Whaley, 2019).

According to Solinska-Nowak et al. (2018), serious games reach a broad audience. Most serious games focus mainly on adults and to a lesser extent on younger people. This audience diversification constitutes a powerful tool for furthering communication and education about DRM.

Serious games provide a satisfying learning and training experience of disaster management (e.g. Safran et al., 2024; Zhao et al., 2023). However, some limitations could potentially hinder their effectiveness. Firstly, although serious games are intended for a wide audience, few examples consider cultural diversity, gender equality and learning from past events (Solinska-Nowak et al., 2018). This limitation is important, because adequate risk management demands participatory strategies involving communities (Tanwattana and Toyoda, 2018). Instead, few studies have addressed the development of diverse resiliency skills through serious games (Villagra et al., 2023; Teague et al., 2021; Neset et al., 2020). The biggest research gap in serious games related to DRR is the lack of empirical evidence about their effectiveness, with a scarcity of quantitative and qualitative studies (Solinska-Nowak et al., 2018; Safran et al., 2024).

The approach of this study is qualitative, involving content analysis of selected serious games and an online survey with open-ended questions to experts.

3.1 Qualitative content analysis of serious games

In order to answer the first research sub-question (“How do serious games communicate and educate on issues related to natural hazards?”), a qualitative content analysis was carried out on serious games for DRM.

We have selected digital games from the wide range of existing examples available. Firstly, we conducted a web search using common search engines, including Yahoo, Google, YouTube, Vimeo, and the Apple iTunes store, using different combinations of the following keywords: serious games, positive communication, simulation, role-play, DRM, DRR, crisis management, emergency, disaster prevention, and disaster mitigation. This search allowed us to find a total of 11 mobile apps, 6 online games, and 20 board games with material available for download from the web (Supplementary material S1, Table S1 in the Supplement). Among the apps and online games, we found four dedicated to volcanoes, six to earthquakes, and seven related to floods.

Subsequently, to limit the scope of this study, we selected only non-commercial games with freely accessible content available in English or Spanish, with a DRM focus in different situations, aimed at young people and adults (age 12 and upwards), with the disasters considered limited to those caused by human interactions with natural hazards (such as volcanic eruptions, earthquakes, floods, droughts, and tsunamis). According to the criteria explained above, a total of 6 examples were selected in this phase from 17 digital games: 3 mobile apps (Earthquake Relief Rescue, Geostorm, and Disaster Rescue Service) and 3 online games (Build a Kit, Disaster Master, and Stop Disasters). Among the former, we found two flooding apps (Geostorm and Disaster Rescue Service) and one focusing on earthquakes (Earthquake Relief Rescue). Two of the online games consider various natural hazards in a detailed way at different levels (Disaster Master and Stop Disasters), while Build a Kit deals with emergencies due to natural hazards in a more generic way.

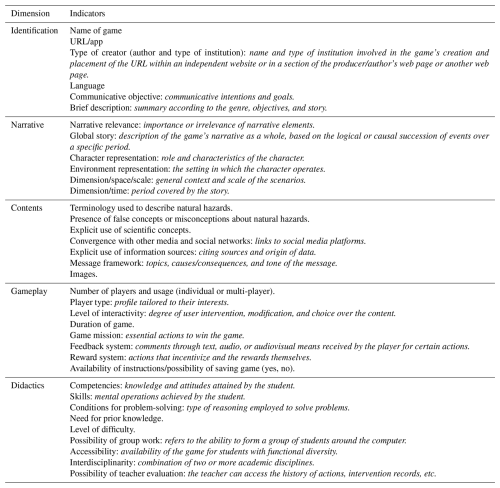

A content analysis of the selected games was then carried out. This is a research method used to quantify and analyse the presence, meaning, and relationships of specific words, themes, or concepts, allowing for inferences to be made about the messages within different units of analysis (e.g. webs sites, journals, games, etc). The type of content analysis used in this research is conceptual analysis. In conceptual content analysis, a concept is chosen for examination, and the analysis involves quantifying and counting its presence. It can be used to identify intentions or communicative tendencies in games; it describes the attitudes or behaviours resulting from communications, revealing patterns in communication content. The dimensions analysed in this study were those proposed by Ouariachi et al. (2017). These authors adapted the theoretical Social Discourse of Video Games Analysis Model (Pérez-Latorre, 2010) into an analytical instrument for games about climate change using the Delphi method. The instrument presents 51 criteria or variables, which are analysed in regards to the messages within the texts, audio, and static and dynamic images of the games. These criteria were classified into five dimensions: identification (features that help identify and locate the game), gameplay (set of properties that describe the player's experience within a given game system), narrative (discursive construction around a complex phenomenon), contents (analysis of the information and messages, transmitted), and educational aspects (referring to competencies, skills and learning). These criteria are described in further detail in Table 1. The analysis of the games was carried out by the authors, who played the games and filled out a form that captured the criteria mentioned above.

3.2 Online survey with open-ended questions to experts

In order to answer the second research sub-question (“What are the educational and communicative elements or characteristics that serious games should have to improve DRM?”), an online survey with open-ended questions for experts was used.

The expert panel was carefully chosen on the basis of their knowledge or skill in the areas of either natural hazards and education or video games. We employed snowball sampling, asking the selected experts to recommend others who also matched our criteria. This study involved individuals with at least five years of professional or experiential knowledge of the research topic, constituting an informed panel and thereby justifying the use of the title “experts” (Mullen, 2003). In total, 21 international experts (from Spain, Italy, Brazil, and USA) took part in the study, with the main areas of expertise of the participants being video games (eight participants) and natural hazards and earth science education (13 participants). The communication process was conducted online. Among the video game respondents, 62.5 % were experts in video game design and the rest were experts on video game programming, development, and production. The panel of experts on natural hazards had different specializations (climate change, floods, earthquakes, volcanoes, and mass movement) and professions (researchers, emergencies experts, a politician, and the partner of a consulting company in urban and territorial planning). To begin with, participants were informed through email about the focus and approach of this study, including the subject, goal, planning and ethical issues, confidentiality and anonymity.

The surveys were conducted online through open-ended questions and in a consensual way. The consensus method aimed to identify indicators and criteria for the design of serious games on natural hazards in order to improve DRM. Two online surveys (Supplementary material S2, Tables S2 and S3 in the Supplement) were created using Google Forms, one addressed to natural hazards experts and earth science educators and one addressed to video games experts. The survey was carried out from 10 March to 20 May 2022.

After sharing the online surveys, the experts in natural hazards and earth science (13) responded during the first week. However, the 42 video games experts required frequent follow-up in order to collect just eight responses. Once all the responses had been collected, codes were formulated based on their analysis using the program MAXQDA (2020). We used this software because it allows the collaborative analysis of qualitative data, helping create a common language in our codebook and reaching a consensus while benefiting from the unique perspectives of each team member.

4.1 Qualitative content analysis of serious games

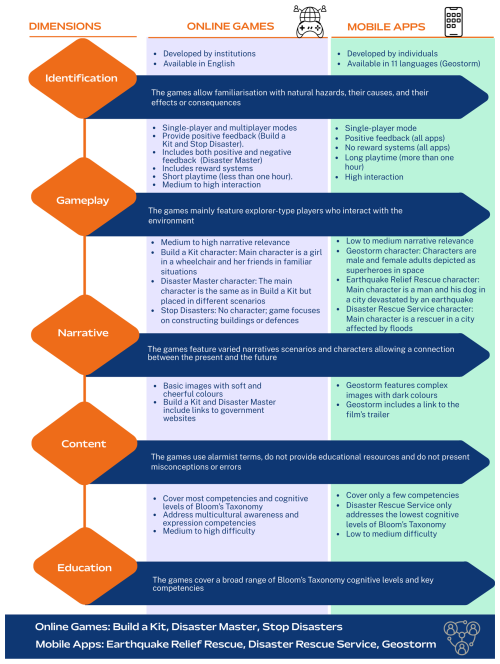

Using the dimensions indicated in Table 1, the results of the analysis of each indicator are shown in Fig. 1 and Supplementary material S3 (Tables S4–S8 in the Supplement).

4.1.1 Identification

The results of the identification dimension can be found in Fig. 1 and Table S4. We detected some differences between the online games and mobile apps. The selected game apps for phones and tablets were created by individuals; in contrast, in the case of the online games, they are created by institutions such as the US Government and the United Nations Office for Disaster and Risk Reduction. All the games were available only in English, except in the case of Geostorm, which has a storyline based on a popular movie, and lets the user choose from 11 languages (Table S4). The games aims to make users familiar with natural hazards in general, raise awareness of their causes and consequences, promote changes in attitude, and develop ideas for action and prevention.

4.1.2 Gameplay

The results of the gameplay dimension are shown in Fig. 1 and Table S5. The online games could be played in both the individual and multi-player mode, while in the case of mobile apps, only individual play is possible. The objective of Build a Kit is to select items for different scenarios; therefore, decisions can be made through teamwork. Disaster Master consists of reading a comic and answering questions in order to check knowledge acquired individually or as a team. Finally, in Stop Disasters, decisions such as which buildings to construct or improve, where to build hospitals, or which barriers to build against natural hazards can also involve teamwork.

The player trait most represented in the games analysed is explorer, with the creative trait also being featured in Stop Disasters, where there is a high level of interactivity over the course of the game, giving players power to intervene.

In terms of game duration, there is a high degree of variability. Build a Kit is the only game that can likely be completed within an hour, while Disaster Master may also be finished in that time, depending on the students' age and comprehension level. The others games feature levels that might also be completed in one hour.

Positive feedback through in-game messages in response to certain actions are abundant in the games, and we only found a reward system in the online examples. None of the games offer the possibility of saving progress in the middle of a level, but if a mission or level is completed, players can then continue the next level at a later time, with the exception of Build a Kit.

4.1.3 Narrative

Across the games, we observed different storylines, highly varied scenarios, and a diversity of characters (Fig. 1 and Table S6). We found that some characters appeared in more than one game, as in the case of Build a Kit and Disaster Master, meaning that students could see them as a continuation of the story, as they already knew the characters. The scenarios used are diverse, ranging from familiar environments such as a teenage girl's bedroom or a living room (Build a Kit), to more unusual settings, such as an international space station (Geostorm).

The game development locations cover different parts of the planet. In the case of Disaster Master, a game created by the US government, the action takes place in different scenarios, all in US territory. Geostorm situates the player in different parts of the world, such as Afghanistan, Dubai (United Arab Emirates), and Florida (US), according to the film on which it is based. Stop Disasters occurs in different parts of the world, depending on the natural catastrophe chosen, coinciding with the areas with the highest incidence of this natural hazard.

Present–future connection is addressed in most of the games. Only Earthquake Relief Rescue and Disaster Rescue Service focus on a natural catastrophe that has already occurred and, therefore, the mission is limited to finding the injured, so players know the consequences. The situation of Geostorm is similar, with the natural catastrophe in progress and the consequences already playing out in the game, but action can still be taken to stop the catastrophe and restore normality. As it is based on a fictional film, Geostorm leans more toward fantasy and is less realistic than the other games, such as Disaster Master.

Finally, in terms of player types, we found a limited range of representation in the games analysed. The main character of Build a Kit is a girl in a wheelchair who has to select items in an emergency situation, and Disaster Master presents the same character in a summer camp surrounded by her friends, each of a different origin. In the case of Geostorm, it includes both female and adult male characters in the role of superheroes, though it does not represent an especially wide range of identities or backgrounds, particularly regarding race, ethnicity, and non-binary perspectives.

4.1.4 Content

The results of the content dimension analysis are presented in Fig. 1 and Table S7. As for the terms used in the games evaluated, we found some rather alarmist terms such as “emergency”, “catastrophe”, and “disaster”. The link to social networks in some of them is merely informative, as in the case of Geostorm, which directs players to the trailer of the film on which it is based. In the case of Build a Kit and Disaster Master, we find that the link provided to the government website leads to a space where more information can be found on natural hazards, as an extension of the knowledge provided by the game.

Build a Kit, Disaster Master, and Stop Disasters feature basic images with soft and cheerful colours. The game with the best image quality and effects is Geostorm, which, simulating the special effects of the film, contains more complex images, although their colours are darker than in the rest of the games.

4.1.5 Learning implications

The results of the analysis of the educational dimension (Fig. 1 and Table S8) show the great potential of the games, which cover a broad spectrum of the cognitive levels of Bloom's Taxonomy (reviewed by Anderson et al., 2001). Bloom's Taxonomy consists of a hierarchical structure of objectives or levels, which allow educators to evaluate the learning process of students; it is also a useful starting point for designing activities to achieve meaningful and lifelong learning. Accordingly, the evaluation criteria related to “Remember” and “Understand” are classified as “Basic”; the criteria related to “Apply” and “Analyse” are classified as “Optimal”; and the criteria related to “Evaluate” and “Create” are classified as “Desirable”. Taking into account these levels, the most complete are Stop Disasters, Disaster Master, and Geostorm, which cover all of them; meanwhile, Earthquake Relief Rescue and Disaster Rescue Service are the two games that cover only the Basic and Optimal learning levels.

Disaster Master and Stop Disasters align with the key competencies for lifelong learning according to the European education curriculum (European Commission, 2019). This connection is relevant, because the curriculum promotes core competencies such as citizenship, sustainability, and learning to learn – objectives closely aligned with the pedagogical goals of serious games in natural hazards education. All the games analysed enable the obtaining of citizenship competence and digital competence. Build a Kit and Disaster Master enable the achievement of the personal, social, and learning to learn competence. In contrast, it is only possible to relate the literacy competence to Disaster Master. Earthquake Relief Rescue and Disaster Rescue are the only games that do not work on the science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) competence. The multiculturalism and cultural awareness and expression competencies are addressed only by the online games (Build a Kit, Disaster Master, and Stop Disasters).

4.2 Online survey with open-ended questions to experts

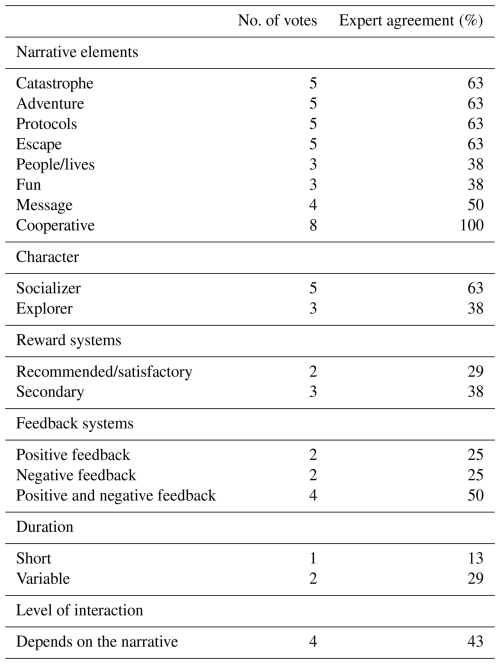

Selected examples of experts' responses to the online surveys are shown in Supplementary Material S4, Table S9 and S10 in the Supplement, while the complete set of thematic categories derived from the analysis is shown in Tables 2 and 3.

Most of the video game experts (63 %) agree that the catastrophic/dramatic and adventure theme, teaching protocols for action, and a possible escape dynamic are key elements in the design of a video game to raise awareness of natural hazards. In line with this catastrophic theme, some experts (33 %) believe that the inclusion of the danger-to-human-life element could enhance empathy on the part of players. Some experts (38 %) add that it is also necessary for the game to be fun enough for children to want to play.

The majority of the video game experts (63 %) agree that the most interesting type of character would be the socializer in a cooperative game dynamic. They remark that for raising awareness of natural hazards, interacting and collaborating with other players who have been affected by disasters could help to generate empathy. Similarly, some of them (33 %) state that the profile of explorers is very interesting for this topic, since natural phenomena lend themselves well to interaction with the environment.

The video game experts recommend including reward systems because they increase engagement and fun. However, some (38 %) remark that the reward system could be considered as a secondary element. If it were included, players may focus on the rewards and disconnect from the main objective, which is to raise awareness and increase knowledge about natural hazards. In the same vein, according to some experts (13 %), the overuse of levels and progression bars could distract from the main objective.

Some video game experts (25 %) agree that positive feedback is the most effective motivation, but it would be interesting to include both positive and negative feedback, so that players can see that their actions have both good and bad repercussions. In this regard, these experts point out that the age of the students must be taken into account; if they are too young, it is more convenient to include positive feedback. However, as they advance in development and enter adulthood, it is advisable to include both. They also emphasize that in order to promote the acquisition of knowledge, feedback should always be constructive.

Regarding the duration of play, it should be a relatively short game, ranging from 15 min to several hours. This duration is recommended for both the full game and for the individual levels. The game can be longer, as long as it has concrete levels or scenarios that can be completed in a short period of time. Some experts (38 %) emphasize that the most important element is the narrative of the game, which must engage players. If this is achieved, the length of the game can even be variable (Table 2).

Finally, the experts recommend that there should be interaction in the game, as it generally engages players and makes it more fun. However, the most prominent element in this context is narrative, since serious games with well-developed storylines may involve less interaction yet still have a powerful impact.

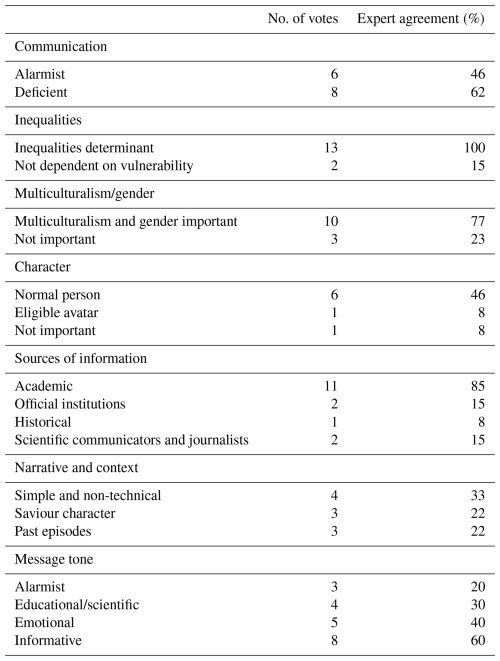

Examples of natural hazards experts' responses to the online surveys are summarized in Table S10, and the analysed categories are shown in Table 3. The natural hazards experts criticize the media for being too alarmist (46 %) and focusing only on high-impact disasters once they have happened, which increases uncertainty and fails to enhance collective and individual prevention. In addition to this, they rarely contact university or technical experts, so they resort to misleading clichés. Therefore, the information they transmit is deficient (62 %) and does not contribute to raising public awareness or to the acquisition of fundamental knowledge about natural hazards.

Table 3Expert agreement on communicative, social, and narrative dimensions in serious games for DRM.

The natural hazards experts also agree that social and structural inequalities significantly influence the vulnerability of a territory or society, since livelihoods, housing, and access to training and information are often unequal and more susceptible to natural hazards. Therefore, a balanced society will be much more resilient than an unequal society. The experts suggest that video games could help players better understand natural hazards and raise awareness among them, i.e. they could be good training in prevention and vulnerability reduction, providing information on self-protection, planning, and emergency management in a playful and enjoyable way. Aspects of multiculturalism and gender should be included in the game, which must consider interracial, intercultural, disability, and gender factors, as these are fundamental for any society. All cultures and genders should be included in video games, given that the whole of society, without exception, can be affected. For this reason, the main character in a game on natural hazards should be an ordinary, responsible, coherent, and supportive person, who has fears and faces them by learning, and who can also fail. In other words, a character with whom players can identify.

The natural hazards experts propose that different sources of information should be used in natural hazard games, such as historical sources and those from official institutions. However, the most important category is academic sources, to avoid introducing erroneous data or information.

With regard to the game narrative and context, most of the natural hazard experts opt for simple, non-technical narratives so that players become familiar with the language and feel that it is a real situation. They mention the figure of a saviour character in the face of natural hazards, making them aware of the resulting environmental and social problems. The last code present among the expert responses is the representation of past natural-hazard-related disasters that have occurred through time. In this way, they convey that natural hazards are things that have always existed and will continue to exist, reinforcing the idea that they are real and have happened at different times in human history.

There was some disagreement about the tone of the message that should be used in video games about natural hazards. The experts opine that an informative tone is important for transferring information combined with an emotional tone to have a greater impact on the user, helping to raise awareness. All of the natural hazards experts reject the alarmist tone except for two, who propose mixing the informative tone with the alarmist tone to prevent the former from being boring and causing indifference. Experts who suggest a purely informative tone also propose a clear and concise message based on science, so that players know what can really happen and how to act in an objective manner.

4.3 Synthesis of findings

In this section, the findings of the qualitative content analysis and the expert responses were compared and further summarized.

4.3.1 Characters

According to the experts' opinions, the main characters of the game should be socializers or explorers with the characteristics of an ordinary person, who reflects their fears, may fail, and who presents a saviour attitude. The experts emphasize that characters should include aspects of multiculturalism and gender and represent interracial people and those with disabilities. The experts agree that games on natural hazards must take gender and cultural differences into account in order to reflect today's society.

The only game with a socializing character in a cooperative dynamic is Disaster Master. The three mobile apps, Geostorm, Disaster Rescue Service, and Earthquake Relief Rescue all feature more exploratory characters. In this sense, Disaster Rescue Service and Earthquake Relief Rescue do present a cooperative dynamic, but there is no opportunity for interaction between players.

4.3.2 Information and message tone

The experts agree that information should be presented in a non-alarmist and non-catastrophist way, and that the information sources used for the development of the games should be mainly academic. In addition, they stress that the tone of the game message should be informative, clear, and concise. It should also have an emotional tone in order to connect with players.

The mobile apps present a more catastrophist and alarmist tone, with people's lives endangered and the adventure factor increased, but they do not use the game narrative to convey information to boost players' preparedness. However, Disaster Master also plays with this aspect of catastrophism and fun, and at the same time, it has a narrative that aims to transmit knowledge and teach protocols for action. Stop Disasters has message texts that explain in a very clear, concise, and simple way the usefulness of each material in preventing the impact of natural hazards and how they should be used. Build a Kit bases its game on teaching protocols for action in case of a natural-hazard-related disaster.

4.3.3 Narrative, dynamics, reward systems, and feedback

The experts recommend that the narrative of the game be simple and non-technical, and it could include references to past episodes. A narrative based on a catastrophic/dramatic and adventure theme is considered ideal by the video game experts. The dynamics of the game should be cooperative, and reward systems and levels or game progression bars should be included as secondary features. Feedback should be included taking into account user age, and positive feedback is especially important. The duration should be between 15 min and several hours, and the game should always be fun.

Build a Kit, Geostorm, Disaster Rescue Service, and Earthquake Relief Rescue present only one reward system, which involves completing a level or scenario, choosing the right tools to make an emergency backpack, opening the office door to escape, or arriving in time to rescue an injured person. The other two games have progression indicators and award points to players when they choose the correct answer or construct a building in a suitable location, but always secondarily. All of the games have player feedback systems, and their durations fall within the experts' recommendation.

5.1 Communication and education on natural hazards through serious games

The serious games analysed in this study present highly varied narratives, which act as key communicative strategies to convey complex information about natural hazards. In most of these games, a connection is made between the present and the future, allowing players to be aware of the impacts of their decisions and experience them directly through the game. This connection fosters experiential learning, enabling knowledge acquisition through active engagement rather than passive observation (Kolb, 2015). By simulating realistic decision-making processes, these games contribute to raising awareness about disaster risks and preparedness.

The central character is usually an explorer with a high level of interactivity. This character type enhances the communicative objective by encouraging players to interact directly with the environment and explore what is happening around them. In doing so, the games simulate real-world hazard scenarios, enhancing players' understanding of risks through experiential exploration.

Examples of positive feedback are common in the games, serving as a mechanism to reinforce correct decisions related to hazard management and preparedness. Only the online games present structured reward systems, which incentivize users to obtain rewards through specific actions. Offline games in particular show limited implementation of motivational strategies, potentially affecting sustained player involvement. Despite these differences, feedback mechanisms in both cases play a critical role in highlighting the consequences of player choices, thereby facilitating the communication of key disaster risk management concepts.

The scenarios used are highly diverse, ranging from familiar environments, such as the home (Build a Kit), to more unfamiliar and spectacular settings, like an international space station (Geostorm). Both types of scenarios can contribute to player motivation: familiar contexts may foster empathy and raise awareness, while surprising and dramatic environments can increase engagement through their novelty. However, this focus on exotic or unrealistic settings may sometimes detract from the realism required for effective risk education, limiting the transferability of learned behaviours to real-world contexts. Although the use of real geographical locations (Stop Disasters) has great educational value, by facilitating an understanding of actual effects and consequences, the absence of mechanisms that explicitly link in-game decisions with real-world preparedness strategies may ultimately weaken the educational impact of these games (Solinska-Nowak et al., 2018).

Few games consider multiculturalism and inclusivity, with only Build a Kit and Disaster Master presenting characters with different backgrounds and individuals with functional diversities, which can be connected to the findings of Solinska-Nowak et al. (2018). Although Geostorm offers language options and portrays both male and female protagonists in leadership roles, such inclusive representations remain isolated cases.

The serious games analysed activate various cognitive levels of Bloom's Taxonomy, with a clear emphasis on higher-order thinking and strategic reasoning. At the foundational levels, such as “Remember” and “Understand”, games like Build a Kit and Disaster Master help learners identify types of natural hazards and recognize emergency protocols, becoming familiar with key terminology and visual warning signs. At the “Application” level, Stop Disasters stands out by requiring players to implement specific decisions regarding housing locations, resource allocation, and infrastructure planning, applying knowledge about vulnerability and resilience. The “Analysis” level is promoted when players must compare the outcomes of different decisions and anticipate their consequences within a dynamic simulation, as in the case of Geostorm, where each choice alters the unfolding scenario. The “Evaluation” level, reached in both Stop Disasters and Geostorm, emerges through the need to prioritize mitigation strategies given limited resources, requiring players to weigh factors such as cost-effectiveness and population protection. Finally, some games, particularly Stop Disasters, achieve the “Creation” level by allowing players to design resilient urban environments from scratch, integrating multiple variables into a coherent action plan. Notably, many of these cognitive processes are directly connected to scientific understanding. For example, players must interpret seismic risks (Stop Disasters), identify flood-prone areas (Stop Disasters and Disaster Master), or respond to changing weather conditions (Geostorm and Disaster Master). Altogether, these games not only enhance student engagement but also support cognitive progression, fostering both scientific literacy and practical decision-making in simulated situations that reflect real-world risk contexts.

In summary, this study demonstrates that serious games communicate and educate players about natural hazards by combining narrative immersion, experiential learning, and decision-making under uncertainty. Through these mechanisms, players experience the consequences of their actions and develop essential competencies for disaster preparedness, including risk assessment and adaptive problem-solving.

5.2 Educational and communicative elements recommended for improving DRM in serious games

The expert opinions are in line with the results of other studies on how to promote social resilience (e.g. Kwok et al., 2016). In this sense, resilience can be strengthened through cooperative dynamics that foster democratic decision-making, shared problem-solving, and the articulation of community values. These processes contribute to the development of collective efficacy, defined as the shared belief in a community's capacity to act effectively when facing adversity (Norris et al., 2008).

Importantly, collective efficacy is not only an outcome of gameplay but can be actively integrated into the game design itself. For instance, the serious game developed by Tanwattana and Toyoda (2018) assigns players community roles such as mayor or first responder and requires them to reach a consensus on mitigation strategies. This mechanism encourages players to coordinate actions, assume responsibility, and experience interdependence. Similarly, the Costa Resiliente game engages participants in spatial co-design exercises to address tsunami risk, simulating community planning processes that reinforce the value of collective agency (Olivares-Rodríguez et al., 2022). The Disaster Response game uses time-limited decision-making across multiple actors, requiring communication, coordination, and distributed leadership to manage emergencies (Klein et al., 2022). These examples illustrate how serious games can support social resilience by embedding collective efficacy directly their core gameplay dynamics.

The use of simple and non-technical narratives based on academic information could promote knowledge of natural risks and hazard consequences and further community preparedness against natural hazards (Kwok et al., 2016). Additionally, incorporating multiculturalism, diversity, and gender awareness into game design can foster inclusivity in DRM and a sense of community and attachment, which are essential factors for building both collective efficacy and resilience in disaster response (Tanwattana and Toyoda, 2018).

Regarding character design, Safran et al. (2024) reveal that player performance is related to the video game narrative and highlights the importance of character traits; so, high-powered avatars lead to a greater increase in attempts to adopt health-promoting behaviours. Similarly, Klimmt et al. (2009) assert that players undergo significant changes in self-perception to align themselves with certain attributes of such characters. Therefore, when players identify with a character, their perceived self-efficacy concerning the acquisition of health-promoting behaviour can increase (Peng, 2008). Therefore, serious games should carefully design avatars and roles that encourage not only engagement but also prosocial attitudes and risk-mitigation behaviours.

Feedback mechanisms in DRM games could be more efficient when based on direct and specific information that achieves objectives and is presented close to the item being evaluated. This feedback should be both positive and empowering (Prensky, 2001). Reward systems are recommended because they enhance motivation and entertainment; however, too many of these could distract from the main objective of the game (Chou, 2016). To maximize educational impact, reward systems in serious games should be carefully aligned with core DRM concepts and designed to recognize meaningful progress in addressing realistic challenges. Rather than relying on superficial incentives, rewards should reinforce key actions such as accurately identifying hazards, prioritizing protective measures, or coordinating mitigation strategies. A tiered reward structure can support this process by offering progressive recognition, for example, smaller rewards for mastering foundational concepts and more significant ones for demonstrating strategic reasoning and complex decision-making (Boyle et al., 2016). Furthermore, cooperative rewards that celebrate group accomplishments, such as successfully planning and executing a community evacuation, can foster social learning and build collective efficacy, a critical factor in facilitating risk-informed action and resilience-building (Kwok et al., 2016). Ensuring an engaging gameplay experience remains essential, as repeated play increases exposure to DRM content and supports long-term knowledge retention (Ouariachi et al., 2019).

A difference of opinion emerges between the experts in relation to the tone of the message. The natural hazards experts recommend a non-alarmist and non-catastrophist tone, while the video game experts agree on a catastrophic/dramatic tone. In this regard, self-efficacy may be diminished by the panic and stress provoked by the perception of both the gravity of a hazard and one's own susceptibility to it, which is important for motivating risk-mitigating action (O'Neill, 2004). Natural hazards frequently provoke negative emotions, including denial and fatalism, which go against the problem-solving orientation necessary for triggering risk-mitigating actions (Safran et al., 2024). However, Zhao et al. (2023) show that these negative emotions are necessary, because they have a greater impact on decision-making than a positive emotional state. Therefore, well-designed video games could balance threats by offering ways to overcome them, incorporating mediated disaster-related problem-solving experiences (Safran et al., 2024). To address this, serious games should strategically combine emotional intensity with mechanisms that reinforce players' sense of agency. A well-designed game might open with immersive, high-stakes scenarios to capture attention and elevate perceived risk, followed by interactive phases that support decision-making through goal-driven challenges, narrative choices, and problem-solving tasks. This progression enables players to experience the gravity of risk while gradually regaining control. By combining threat perception with coping opportunities in collaborative, feedback-rich environments, serious games can foster adaptive engagement, enhance risk awareness, and promote informed mitigation behaviours, without emotionally overwhelming users (Vervoort et al., 2022; Zhao et al., 2023).

To summarize, serious games should integrate cooperative mechanics, multicultural and inclusive narratives, empowering character designs, feedback aligned with learning goals, and emotionally balanced communication strategies. Through these elements, they can effectively foster disaster preparedness, promote resilience, and support the development of informed, proactive communities.

In response to the need for engaging and motivational approaches to education and communication, video games have been recognized as one of the most useful strategies for teaching DRR (e.g. Hawthorn et al., 2021). However, the impacts of video games on players in terms of improving DRM remain relatively unstudied (e.g. Safran et al., 2024). This work offers novel insights by combining a content analysis of serious games with expert perspectives and by identifying and validating specific communicative and educational features that can significantly enhance the effectiveness of DRM education.

To better understand how to inform and educate the public about natural hazards through serious games, this research identifies the most desirable game characteristics, as determined through an online survey with open-ended questions to experts. These features include: exploratory characters in a cooperative dynamic; simple and non-technical narratives based on academic sources; themes of multiculturalism, diversity, and gender; fun and short games; and a constructive feedback system, with rewards having a secondary presence. The results provide valuable and evidence-based design guidelines for developers and educators, offering practical strategies to maximize the educational potential of serious games in DRM contexts.

The proposed features were used to evaluate selected online games and mobile apps to identify which formats best achieve educational and communicative goals in DRM. The findings indicate that only the online games align with the narrative structures emphasized by the experts, fulfilling their educational purpose more thoroughly. In contrast, mobile apps prioritize interaction, both, between the player and game controls, and between the character and the game environment, enhancing enjoyment and motivation to play but often at the expense of deeper educational value. Nonetheless, online games were found to provide greater educational benefits, both through the explicit messages they convey and the way their gameplay progresses. Notably, only three online examples (Build a Kit, Disaster Master, and, Stop Disasters) integrate themes of multiculturalism, diversity, and gender, while also offering geographically relevant information on areas prone to natural hazards. These aspects not only support knowledge acquisition but also foster greater social awareness, thereby offering valuable guidance to teachers in selecting games for implementation in the classroom.

The limitations of this study are related to the subjective nature of qualitative analyses, due to their focus on interpreting meaning and the meaning-making process. To address this, we employed a combined qualitative approach based on two complementary methods: a thematic content analysis of selected serious games and an online survey with open-ended questions to experts in natural hazards and educational video games. Additionally, the sample size of the expert panel, while sufficient for exploratory qualitative research, may limit the generalizability of the findings. Despite this, the participants were carefully selected based on their expertise in DRM, ensuring the relevance and validity of their contributions. This approach provided depth and nuance; nonetheless, future research would benefit from experimental or mixed-method designs that allow for causal inference and generalizability. In particular, subsequent studies could address specific research questions to deepen our understanding of how design elements influence learning and behavioural outcomes in DRM: (1) How does narrative tone (e.g. catastrophic vs. non-alarmist) affect players' motivation to adopt DRM-related behaviours? (2) In what ways do feedback and reward structures (e.g. immediate vs. delayed) impact decision-making and knowledge retention? (3) How do specific gameplay mechanics (e.g. collaborative vs. competitive strategies or resource discovery) shape the development of problem-solving skills in simulated disaster contexts?

Overall, when grounded in sound educational principles, serious games have the potential to become transformative tools that reshape how individuals and societies engage with natural risks. By explicitly integrating knowledge acquisition, emotional engagement, interactive learning, and inclusive narratives with cooperative dynamics, these games can foster critical thinking, promote adaptive behaviours, and contribute to building a more resilient and prepared society.

The complete dataset comprising the expert interviews is available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17255147 (Vázquez-Vílchez et al., 2025).

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-25-3939-2025-supplement.

MVV, RCM, and TOP conceptualized the study and designed the methodology; MVV, RCM, and TOP conducted the content analysis of serious games; MVV, RCM and TOP organized the expert survey and collected the data; MVV, RCM, and TOP performed the data analysis; MVV and TOP drafted the manuscript; MVV, RCM, and TOP reviewed and edited the manuscript.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors.

The authors would like to thank Adam Cundy for his support in revising and improving the English language of an earlier version of the article and the two reviewers for their insightful comments.

This research was supported by project PID2024-160481OB-I00 (MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033/ERDF, EU) and by the Junta de Andalucía (research group HUM-613).

This paper was edited by Robert Sakic Trogrlic and reviewed by Miguel Angel Trejo Rangel and one anonymous referee.

ADRC: Natural Disasters Data Book 2023: An Analytical Overview, Tech. rep., Asian Disaster Reduction Center, https://www.adrc.asia/publications/databook/ORG/databook_2023/pdf/DataBook2023.pdf (last access: 24 September 2025), 2023. a

Akhtar, M. K., De La Chevrotière, C., Tanzeeba, S., Tang, T., and Grover, P.: A serious gaming tool: Bow River Sim for communicating integrated water resources management, J. Hydrol., 22, 491–509, https://doi.org/10.2166/hydro.2020.089, 2020. a

Altan, B., Gürer, S., Alsamarei, A., Demir, D. K., Düzgün, H. Ş., Erkayaoğlu, M., and Surer, E.: Developing serious games for CBRN-e training in mixed reality, virtual reality, and computer-based environments, Int. J. Disast. Risk. Re., 77, 103022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2022.103022, 2022. a

Anderson, L. W., Krathwohl, D. R., Airasian, P., Cruikshank, K., Mayer, R., Pintrich, P., Raths, J., and Wittrock, M.: A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching, and Assessing: A Revision of Bloom's Taxonomy of Educational Objectives, Addison Wesley Longman, Inc., New York, ISBN 978-0-321-08405-7, 2001. a

Bellotti, F., Kapralos, B., Lee, K., Moreno-Ger, P., and Berta, R.: Assessment in and of serious games: an overview, Advances in Human-Computer Interaction, 2013, 1–11, https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/136864, 2013. a

Bogost, I.: Persuasive Games: The Expressive Power of Videogames, The MIT Press, https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/5334.001.0001, 2007. a

Boyle, E. A., Hainey, T., Connolly, T. M., Gray, G., Earp, J., Ott, M., Lim, T., Ninaus, M., Ribeiro, C., and Pereira, J.: An update to the systematic literature review of empirical evidence of the impacts and outcomes of computer games and serious games, Computers and Education, 94, 178–192, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2015.11.003, 2016. a

Bylieva, D. S., Lobatyuk, V. V., and Nam, T. A.: Serious games as innovative tools in HR policy, IOP C. Ser. Earth Env., 337, 012048, https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/337/1/012048, 2019. a

Chou, Y.-k.: Actionable Gamification: Beyond Points, Badges, and Leaderboards, Octalysis Media, Fremont, CA, ISBN 978-0-692-67333-1, 2016. a

Clerveaux, V., Spence, B., and Katada, T.: Using game technique as a strategy in promoting disaster awareness in Caribbean multicultural societies: The Disaster Awareness Game, Journal of Disaster Research, 3, 321–333, https://doi.org/10.20965/jdr.2008.p0321, 2008. a

Connolly, T. M., Boyle, E. A., MacArthur, E., Hainey, T., and Boyle, J. M.: A systematic literature review of empirical evidence on computer games and serious games, Computers and Education, 59, 661–686, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2012.03.004, 2012. a, b

Corti, K.: Games-Based Learning: A Serious Business Application, Tech. rep., PIXELearning Limited, https://www.cs.auckland.ac.nz/courses/compsci777s2c/lectures/Ian/serious%20games%20business%20applications.pdf (last access: 24 September 2025), 2006. a

Courbet, D., Bernard, F., Joule, R.-V., Halimi-Falkowicz, S., and Guéguen, N.: Small clicks, great effects: the immediate and delayed influence of websites containing serious games on behavior and attitude, Int. J. Advert., 35, 949–969, https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2015.1082226, 2016. a

Cremers, A., Stubbé, H., Van Der Beek, D., Roelofs, M., and Kerstholt, J.: Does playing the serious game B-SaFe! make citizens more aware of man-made and natural risks in their environment?, J. Risk Res., 18, 1280–1292, https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2014.919513, 2015. a, b

de Freitas, S.: Are games effective learning tools? A review of educational games, Journal of Educational Technology and Society, 21, 74–84, 2018. a

European Commission: Key Competences for Lifelong Learning, Tech. rep., European Commission, https://doi.org/10.2766/569540, 2019. a

Feng, Z., González, V. A., Amor, R., Spearpoint, M., Thomas, J., Sacks, R., Lovreglio, R., and Cabrera-Guerrero, G.: An immersive virtual reality serious game to enhance earthquake behavioral responses and post-earthquake evacuation preparedness in buildings, Adv. Eng. Inform., 45, 101118, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aei.2020.101118, 2020. a, b

Frasca, G.: Play the Message: Play, Game and Videogame Rhetoric, PhD thesis, IT University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark, https://www.dropbox.com/scl/fi/cn123tbyik9od74kefw7n/Frasca_Play_the_Message_PhD.pdf?rlkey=xmpm0hj3scd65hvngsvef372n&dl=0 (last access: 24 September 2025), 2007. a

Gampell, A. V. and Gaillard, J. C.: Stop disasters 2.0: video games as tools for disaster risk reduction, International Journal of Mass Emergencies and Disasters, 34, 283–316, https://doi.org/10.1177/028072701603400205, 2016. a, b

Gordon, J. N. and Yiannakoulias, N.: A serious gaming approach to understanding household flood risk mitigation decisions, J. Flood Risk Manag., 13, https://doi.org/10.1111/jfr3.12648, 2020. a

Hawthorn, S., Jesus, R., and Baptista, M. A.: A review of digital serious games for tsunami risk communication, International Journal of Serious Games, 8, 21–47, https://doi.org/10.17083/ijsg.v8i2.411, 2021. a

Heintz, S. and Law, E. L.-C.: The game genre map: a revised game classification, in: Proceedings of the 2015 Annual Symposium on Computer-Human Interaction in Play, ACM, London UK, 175–184, https://doi.org/10.1145/2793107.2793123, 2015. a

Heintz, S. and Law, E. L.-C.: Digital educational games: methodologies for evaluating the impact of game type, ACM T. Comput.-Hum. Int., 25, 1–47, https://doi.org/10.1145/3177881, 2018. a

Heinzlef, C., Lamaury, Y., and Serre, D.: Improving climate change resilience knowledge through a gaming approach: application to marine submersion in the city of Punaauia, Tahiti, Environmental Advances, 15, 100467, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envadv.2023.100467, 2024. a, b

Hellín, C. J., Calles-Esteban, F., Valledor, A., Gómez, J., Otón-Tortosa, S., and Tayebi, A.: Enhancing student motivation and engagement through a gamified learning environment, Sustainability, 15, 14119, https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914119, 2023. a

IFRC: World Disasters Report 2020, Tech. rep., International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, Geneva, ISBN 978-2-9701289-5-3, 2020. a

Klein, M. G., Jackson, P. L., and Mazereeuw, M.: Teaching humanitarian logistics with the disaster response game, Decision Sciences Journal of Innovative Education, 20, 158–169, https://doi.org/10.1111/dsji.12261, 2022. a

Klimmt, C., Hefner, D., and Vorderer, P.: The video game experience as “true” identification: a theory of enjoyable alterations of players' self-perception, Commun. Theor., 19, 351–373, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2009.01347.x, 2009. a

Kolb, D. A.: Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development, Pearson Education, Inc, Upper Saddle River, New Jersey, 2nd Edn., ISBN 978-0-13-389240-6, 2015. a, b

Kwok, A. H., Doyle, E. E., Becker, J., Johnston, D., and Paton, D.: What is “social resilience”? Perspectives of disaster researchers, emergency management practitioners, and policymakers in New Zealand, Int. J. Disast. Risk. Re., 19, 197–211, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2016.08.013, 2016. a, b, c

Lamb, R. L., Annetta, L., Firestone, J., and Etopio, E.: A meta-analysis with examination of moderators of student cognition, affect, and learning outcomes while using serious educational games, serious games, and simulations, Comput. Hum. Behav., 80, 158–167, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.10.040, 2018. a

Lavell, A., Oppenheimer, M., Diop, C., Hess, J., Lempert, R., Li, J., Muir-Wood, R., Myeong, S., Moser, S., Takeuchi, K., Cardona, O. D., Hallegatte, S., Lemos, M., Little, C., Lotsch, A., and Weber, E.: Climate change: New dimensions in disaster risk, exposure, vulnerability, and resilience, in: Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaptation, Vol. 9781107025066, Cambridge University Press, UK, https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139177245.004, 25–64, 2012. a, b

Liao, K.-H., Chiang, Y.-S., and Chan, J. K. H.: The levee dilemma game: a game experiment on flood management decision-making, Int. J. Disast. Risk. Re., 90, 103662, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2023.103662, 2023. a

Macholl, J. D., Roberts, H., Steptoe, H., Sun, S., Angus, M., Davenport, C., Luscombe, W., Rolker, H. B.., Pope, E. C. D., Dawkins, L. C., Munday, G., Giles, D., Lam, T., Deutloff, J., Champion, A. J., Bloomfield, H. C., Mendes, J., Speight, L., Bradshaw, C. D., and Wyatt, F.: A collaborative hackathon to investigate climate change and extreme weather impacts in justice and insurance settings, Weather, 79, 196–203, 2024. a

Magnuszewski, P., Królikowska, K., Koch, A., Pająk, M., Allen, C., Chraibi, V., Giri, A., Haak, D., Hart, N., Hellman, M., Pan, D., Rossman, N., Sendzimir, J., Sliwinski, M., Stefańska, J., Taillieu, T., Weide, D., and Zlatar, I.: Exploring the role of relational practices in water governance using a game-based approach, Water-Sui., 10, 346, https://doi.org/10.3390/w10030346, 2018. a

Medina, L.: Tecnologías Emergentes al Servicio de La Educación, Aprender y educar con las tecnologías del Siglo XXI, 35–47, ISBN 978-958-99999-2-9, 2012. a

Mezirow: Transformation theory of adult learning, in: In Defense of the Lifeworld: Critical Perspectives on Adult Learning, edited by: Welton, M., State University of New York Press, New York, 37–90, ISBN 0-7914-2539-8, 1995. a

Mossoux, S., Delcamp, A., Poppe, S., Michellier, C., Canters, F., and Kervyn, M.: Hazagora: will you survive the next disaster? – A serious game to raise awareness about geohazards and disaster risk reduction, Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci., 16, 135–147, https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-16-135-2016, 2016. a

Mouaheb, H., Fahli, A., Moussetad, M., and Eljamali, S.: The serious game: what educational benefits?, Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 46, 5502–5508, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.06.465, 2012. a

Mullen, P. M.: Delphi: Myths and Reality, Journal of Health Organization and Management, 17, 37–52, https://doi.org/10.1108/14777260310469319, 2003. a

Neset, T.-S., Andersson, L., Uhrqvist, O., and Navarra, C.: Serious gaming for climate adaptation – assessing the potential and challenges of a digital serious game for urban climate adaptation, Sustainability, 12, 1789, https://doi.org/10.3390/su12051789, 2020. a

Norris, F. H., Stevens, S. P., Pfefferbaum, B., Wyche, K. F., and Pfefferbaum, R. L.: Community resilience as a metaphor, theory, set of capacities, and strategy for disaster readiness, Am. J. Commun. Psychol., 41, 127–150, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-007-9156-6, 2008. a

Olivares-Rodríguez, C., Villagra, P., Mardones, R. E., Cárcamo-Ulloa, L., and Jaramillo, N.: Costa Resiliente: a serious game co-designed to foster resilience thinking, Sustainability, 14, 16760, https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416760, 2022. a

O'Neill, B.: Handbook of Game Theory, Vol. 3, Game. Econ. Behav., 46, 215–218, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0899-8256(03)00172-6, 2004. a

Ouariachi, T., Gutiérrez-Pérez, J., and Olvera-Lobo, M.-D.: Criterios de Evaluación de Juegos En Línea Sobre Cambio Climático: Aplicación Del Método Delphi Para Su Identificación, Revista mexicana de investigación educativa, 22, 445–474, 2017. a

Ouariachi, T., Olvera-Lobo, M. D., Gutiérrez-Pérez, J., and Maibach, E.: A framework for climate change engagement through video games, Environ. Educ. Res., 25, 701–716, https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2018.1545156, 2019. a

Peng, W.: The mediational role of identification in the relationship between experience mode and self-efficacy: enactive role-playing versus passive observation, Cyberpsychol. Behav., 11, 649–652, https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2007.0229, 2008. a

Pérez-Latorre, Ó.: Análisis de la significación del videojuego fundamentos teóricos del juego, el mundo narrativo y la enunciación interactiva como perspectivas de estudio del discurso, Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona, http://hdl.handle.net/10230/11835 (last access: 24 September 2025), 2010. a

Pineda-Martínez, M., Llanos-Ruiz, D., Puente-Torre, P., and García-Delgado, M. Á.: Impact of video games, gamification, and game-based learning on sustainability education in higher education, Sustainability, 15, 13032, https://doi.org/10.3390/su151713032, 2023. a

Poděbradská, M., Noel, M., Bathke, D., Haigh, T., and Hayes, M.: Ready for drought? A community resilience role-playing game, Water-Sui., 12, 2490, https://doi.org/10.3390/w12092490, 2020. a

Prensky, M.: The games generations: how learners have changed, in: Digital Game-Based Learning, Vol. 1, McGraw-Hill New York, New York, Chapter 2, ISBN 0-07-136344-0, 2001. a

Ramírez-Cogollor, J. L.: Gamificación mecánicas de juegos en tu vida personal y profesional, Sclibro, Madrid (España), ISBN 978-84-941272-6-7, 2014. a

Safran, E. B., Nilsen, E., Drake, P., and Sebok, B.: Effects of video game play, avatar choice, and avatar power on motivation to prepare for earthquakes, Int. J. Disast. Risk. Re., 101, 104184, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2023.104184, 2024. a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i, j, k, l

Sáiz-Manzanares, M. C., Martin, C. F., Alonso-Martínez, L., and Almeida, L. S.: Usefulness of digital game-based learning in nursing and occupational therapy degrees: a comparative study at the University of Burgos, Iint. J. Env. Res. Pub. He., 18, 11757, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182211757, 2021. a

Sawyer, B. and Smith, P.: Serious Games Taxonomy, https://thedigitalentertainmentalliance.files.wordpress.com/2011/08/serious-games-taxonomy.pdf (last access: 24 September 2025), 2008. a

Schueller, L., Booth, L., Fleming, K., and Abad, J.: Using serious gaming to explore how uncertainty affects stakeholder decision-making across the science-policy divide during disasters, Int. J. Disast. Risk. Re., 51, 101802, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101802, 2020. a

Sharpe, J.: Understanding and unlocking transformative learning as a method for enabling behaviour change for adaptation and resilience to disaster threats, Int. J. Disast. Risk. Re., 17, 213–219, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2016.04.014, 2016. a

Solinska-Nowak, A., Magnuszewski, P., Curl, M., French, A., Keating, A., Mochizuki, J., Liu, W., Mechler, R., Kulakowska, M., and Jarzabek, L.: An overview of serious games for disaster risk management – prospects and limitations for informing actions to arrest increasing risk, Int. J. Disast. Risk. Re., 31, 1013–1029, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2018.09.001, 2018. a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i, j, k, l

Suarez, P., de Suarez, J. M., Koelle, B., and Boykoff, M.: Serious Fun: Scaling up community-based adaptation through experiential learning, in: Community-Based Adaptation to Climate Change, Routledge, London UK, 1st Edn., 136–151, https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203105061-11, 2014. a

Sullivan-Wiley, K. A., Short Gianotti, A. G., and Casellas Connors, J. P.: Mapping vulnerability: opportunities and limitations of participatory community mapping, Appl. Geogr., 105, 47–57, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2019.02.008, 2019. a, b

Tanes, Z.: Shall we play again? The effects of repetitive gameplay and self-efficacy on behavioural intentions to take earthquake precautions, Behaviour and Information Technology, 36, 1037–1045, https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929x.2017.1334089, 2017. a

Tanes, Z. and Cho, H.: Goal setting outcomes: examining the role of goal interaction in influencing the experience and learning outcomes of video game play for earthquake preparedness, Comput. Hum. Behav., 29, 858–869, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.11.003, 2013. a

Tanwattana, P. and Toyoda, Y.: Contributions of gaming simulation in building community-based disaster risk management applying Japanese case to flood prone communities in Thailand upstream area, Int. J. Disast. Risk. Re., 27, 199–213, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2017.10.007, 2018. a, b, c, d, e, f, g

Teague, A., Sermet, Y., Demir, I., and Muste, M.: A collaborative serious game for water resources planning and hazard mitigation, Int. J. Disast. Risk. Re., 53, 101977, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101977, 2021. a, b, c, d

Tolks, D., Schmidt, J. J., and Kuhn, S.: The role of AI in serious games and gamification for health: scoping review, JMIR Serious Games, 12, e48258, https://doi.org/10.2196/48258, 2024. a

Trejo-Rangel, M. A., Marchezini, V., Rodriguez, D. A., Dos Santos, D. M., Gabos, M., De Paula, A. L., Santos, E., and Do Amaral, F. S.: Incorporating social innovations in the elaboration of disaster risk mitigation policies, Int. J. Disast. Risk. Re., 84, 103450, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2022.103450, 2023. a

Tsai, M.-H., Chang, Y.-L., Shiau, J.-S., and Wang, S.-M.: Exploring the effects of a serious game-based learning package for disaster prevention education: the case of battle of flooding protection, Int. J. Disast. Risk. Re., 43, 101393, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2019.101393, 2020. a, b

Van Kerkhoff, L. and Lebel, L.: Linking knowledge and action for sustainable development, Annu. Rev. Env. Resour., 31, 445–477, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.energy.31.102405.170850, 2006. a

Vázquez-Vílchez, M., Carmona-Molero, R., and Ouariachi-Peralta, T.: Expert interviews on communicating and educating more effectively on natural risk issues to improve disaster risk management (v1.0.0), Zenodo [data set], https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17255147, 2025. a

Vervoort, J., Mangnus, A., McGreevy, S., Ota, K., Thompson, K., Rupprecht, C., Tamura, N., Moossdorff, C., Spiegelberg, M., and Kobayashi, M.: Unlocking the potential of gaming for anticipatory governance, Earth System Governance, 11, 100130, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esg.2021.100130, 2022. a

Villagra, P., Peña Y Lillo, O., Ariccio, S., Bonaiuto, M., and Olivares-Rodríguez, C.: Effect of the Costa Resiliente serious game on community disaster resilience, Int. J. Disast. Risk. Re., 91, 103686, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2023.103686, 2023. a, b, c

Vogel, J. J., Vogel, D. S., Cannon-Bowers, J., Bowers, C. A., Muse, K., and Wright, M.: Computer gaming and interactive simulations for learning: a meta-analysis, J. Educ. Comput. Res., 34, 229–243, https://doi.org/10.2190/flhv-k4wa-wpvq-h0ym, 2006. a

Wang, K. and Davies, E.: A water resources simulation gaming model for the invitational drought tournament, J. Environ. Manage., 160, 167–183, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2015.06.007, 2015. a

Weyrich, P., Ruin, I., Terti, G., and Scolobig, A.: Using serious games to evaluate the potential of social media information in early warning disaster management, Int. J. Disast. Risk. Re., 56, 102053, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2021.102053, 2021. a, b

Whaley, B.: Virtual earthquakes and real-world survival in Japan's Disaster Report Video Game, The Journal of Asian Studies, 78, 95–114, https://doi.org/10.1017/s0021911818002620, 2019. a, b

Wiek, A. and Iwaniec, D.: Quality criteria for visions and visioning in sustainability science, Sustain. Sci., 9, 497–512, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-013-0208-6, 2014. a

Wilson, K. A., Bedwell, W. L., Lazzara, E. H., Salas, E., Burke, C. S., Estock, J. L., Orvis, K. L., and Conkey, C.: Relationships between game attributes and learning outcomes: review and research proposals, Simulation and Gaming, 40, 217–266, https://doi.org/10.1177/1046878108321866, 2009. a

Yamori, K.: Disaster risk sense in Japan and gaming approach to risk communication, International Journal of Mass Emergencies and Disasters, 25, 101–131, https://doi.org/10.1177/028072700702500201, 2007. a

Yamori, K.: The roles and tasks of implementation science on disaster prevention and reduction knowledge and technology: from efficient application to collaborative generation, Journal of Integrated Disaster Risk Management, 1, 48–58, https://doi.org/10.5595/idrim.2011.0009, 2011. a

Zhao, X., Wang, S., Gao, J., Chen, J., Zhang, A., and Wu, X.: A game model and numerical simulation of risk communication in metro emergencies under the influence of emotions, Int. J. Disast. Risk. Re., 97, 104046, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2023.104046, 2023. a, b, c