the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Invited perspectives: “Natural hazard management, professional development and gender equity: let's get down to business”

Valeria Cigala

Heidi Kreibich

- Article

(826 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(60 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Women constitute a minority in the geoscience professional environment (around 30 %; e.g. UNESCO, 2015; Gonzales, 2019; Handley et al., 2020), and as a consequence, they are underrepresented in disaster risk reduction (DRR) planning. After examining the Sendai framework documents and data outputs, Zaidi and Fordham (2021) pointed out that the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030 (SFDRR) has failed to promote women and girls' inclusion in disaster policy effectively. In addition, it represents a missed opportunity to tackle gender-based issues in DRR (even beyond the female–male dichotomy). Nevertheless, practical actions have been promoted and applied in several contexts with promising results, but often they only remain lessons learned in localised environments (Zaidi and Fordham, 2021). Instead, the global gender gap index, which includes political empowerment, economic participation and opportunity, educational attainment, health, and survival, reveals that the average distance completed to parity is only 68 % in 2019. Although the gap closing rate has constantly improved, it will take about 135.6 years to close it completely (WEF, 2021). These numbers do not yet account for 2020–2021 data, where the global pandemic has more strongly impacted women, their career, their opportunities, and their health in comparison with men (e.g. Alon et al., 2020; Chandler et al., 2021; Yildirim and Eslen-Ziya, 2021).

Gender recognition and representation do not affect the sole career sphere or the policy and DRR agenda. They even impact our vision about gender and gender equity in the actions, behaviours, and intentions before, during, and after natural hazards. Based on our literature search, we recognise that for most disaster-related papers, gender was merely used as a dichotomous variable (usually together with a set of other socio-demographic variables) to test assessments and model results, which are the core of the papers. When gender results in a significant variable, it is rarely contextualised with the vulnerability of women and men in the socio-cultural and political environment of the study site (exceptions are Finucane et al., 2000; Cvetković et al., 2018; Mondino et al., 2021). Instead, stereotypical biological sex motivations are more often considered (e.g. women are more vulnerable due to housekeeping and child-bearing responsibilities; Paradise, 2005; De Silva and Jayathilaka, 2014). Gender as a social structure has a complex interaction at both the individual and communal levels (Risman, 2018), able to influence the capacity of communities to withstand the negative occurrence of natural hazards actively. In our opinion, if we fail to understand that, we fail in risk reduction strategies and effective planning. To this point, we recognise that gender is poorly investigated in DRR papers. It is much more considered in social science articles, oriented to history, societies, and social behaviours in general. Moreover, gender diversity is scarce in the professional sphere of natural hazards, with consequences for managing vulnerabilities and career opportunities in academic research.

Thus, despite the global gender gap index decreasing over the years, challenges to gender equity (e.g. reaching equal political power, economic participation, educational attainment) are still strongly perceived. Therefore, practical actions, solutions, and strategies to close the gender gap must continue to be tested and researched, the actions' efficacy assessed, and their effects adequately monitored. In this “invited perspective”, we put individuals identifying themselves with genders that are a minority in the field of natural hazards, i.e. female and non-binary genders, at the centre of the discussion. We aim to concretely contribute to understanding the standpoint of these minorities who are often underrepresented, unheard, and poorly considered professionally in DRR policy and practice. Thus, this perspective qualitatively explores a collection of 121 opinions of individuals identifying themselves as female and one opinion of an individual identifying themselves as non-binary working in the broad field of natural hazards (in academia and in the industry as practitioners or policymakers). The respondents are disproportionate towards the female gender; as a result, most of the issues and solutions proposed and discussed in the present paper revolve around the female gender.

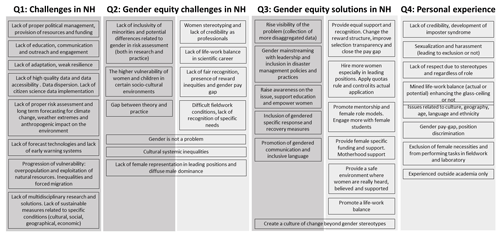

The questionnaire was short and explorative, examining opinions on the challenges (Q1) related to natural hazards in general and those concerning (Q2) natural hazards and gender equity, plus (Q3) opinions on the most urgent solutions to withstand gender inequities. The last question (Q4) asked for the respondent's gender-related challenges experienced during their career (or studies). Questions have been purposely developed following a general to local scale, narrowing down their general perspectives in natural hazards research and concluding with one's own experience. We have chosen open questions to let the professionals personally provide the most critical priority for action, related challenges, and solutions. We have categorised all the answers through qualitative text analysis. Each response to the four questions has been analysed independently by the three authors. A final discussion allowed us to assign all responses to definitive categories to the key concepts expressed. All categories are shown in Fig. 1. The survey included socio-demographic variables (profession, educational level, and country of residence) characterising the respondents. The data collection used a random approach, where only interested participants offered their time participating in the survey; we found a heterogeneous (and disproportionate) representation of those demographic categories. The survey was conducted in April 2021 online on EUSurvey, a service created and managed by the European Commission. The survey was fully anonymised, and no user-related data were saved. No respondent's sensitive information (e.g. name, surname, or age) was requested. The survey, i.e. link to the questionnaire with a short explanatory and motivational text, was advertised via email to the EGU NHESS author list and to a list of female professionals whom the authors had collected in their networks. Moreover, the survey was advertised on social media, particularly on Twitter, LinkedIn, and Facebook, through the personal accounts of the first two authors.

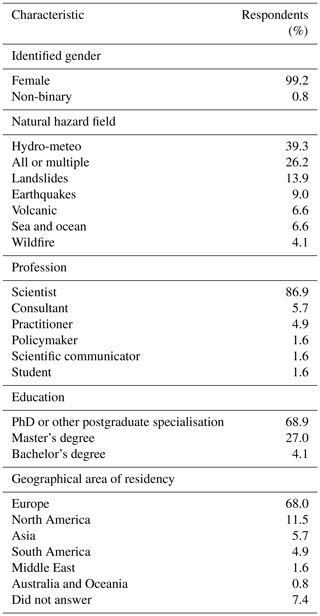

Among 122 people who filled out the questionnaire, 121 identified as female and one as non-binary. Since non-binary people are also underrepresented, we decided to include their answer in the analysis. Table 1 summarises the demographics of the respondents. Individuals identifying as male were excluded from the survey via a first barrier question about the gender. The sample is dominated by female European scientists working on hydro-meteorological hazards or multi-hazards.

The responses to each of the four questions have been categorised into two groups: related to (i) natural hazards (dark grey in Fig. 1) and (ii) professional development (light grey in Fig. 1). This division is because respondents oriented their answers based on personal judgement, progressed professional experience, and cognitive and emotional background. In the following chapters, direct quotes of responses received are identified with ID and a sequential number (from 1 to 122 for each question). The categories for each question and the related percentage of responses are also included in the Supplement in the form of a table.

Figure 1Summary of the categories of challenges and solutions in natural hazards (NH) related to gender equity and personal experiences. In dark grey are natural-hazard-related responses while in light grey are responses related to professional and career development.

2.1 Natural hazards' biggest challenges

Natural hazards and disaster reconnaissance have been widely investigated among professional, government, and academic experts. Somewhat lesser is the state of the arts regarding the natural hazards community's grand challenges to direct new approaches for investigation. For this reason, we asked our respondents to express the most critical challenge in natural hazards research (Q1) with no limiting context. The importance of starting from global to local (from natural hazards in general to gender equity and personal experience) aimed at helping the interviewee to get into the topic and value their professional knowledge and expertise about natural hazards. In addition, despite the question being explorative, we wanted to check whether women would have connected the biggest challenges of natural hazards to broad concepts of vulnerability, fragile communities, vulnerable groups, and similar. This is because it has always been one of the greatest stereotypes associated with women (i.e. the most dedicated to caring activities and fragile). Instead, the most perceived challenge (44.3 %) is related to climate change and extreme events, focusing on the difficulties of long-term forecasting and predictive models due to the interchange of anthropogenic impacts on the environment.

Similarly, Wartman et al. (2020) found that computational simulation and forecasting are essential tools for decision making and planning, but they still represent a challenge to the professional community. This result evidences that women professionals in the natural hazard community do not differ from their counterparts. None of their possible more prominent caring attitudes and sensitivities can affect their perceptions of their work priorities and directions. To continue, respondents believed that one of the most evident constraints is the high complexity and data requirements for model development to provide a reliable forecast concerning the short observation periods, which increases uncertainty. As evidenced by the 10 % of the sample, problems with data are multifaceted, and data quality, accessibility, and transparency are an utmost priority. This is especially true when

research solutions are […] translated into operational procedures […] without considering the actual legal framework or the availability of data, referring to a resolution [being too small or too large] that in practice is not used by the managing authorities (ID84).

This mismatch can generate “confusion among practitioners and managing authorities”, with difficulties harmonising the results and consequent miscommunication risks. Uncertainty is considered a prominent issue in this regard, especially concerning the unpredictability of climate change as widely acknowledged among scientists. These are challenging communication efforts, especially when communities lack trust in authorities' decisions or due to competitive objectives and interests.

Enhancing communication is one of the top priorities for 17 interviewees (13.9 %), highlighting that “our biggest challenge as scientists is to convince the general public and politicians about our scientific findings and to be able to communicate them properly, in a language that they can understand” (ID30). Problems with comprehension may also derive from a “lack of consensus concerning basic definitions (hazard, risk, vulnerability, resilience), leading to misunderstandings or misuse of these terms” (ID52) that can affect authorities who can neglect the information received. A total of 27 % of interviewees also pointed to a lack of proper political management and insufficient resources and funding. In this regard, even more prominent is the need for a

stronger dialogue between scientists and governments, [for the] identification of strategies and solutions that might be effectively implemented in the real world, thus promoting a research that might really contribute to the solution of real-life problems and not remain in the academic discourses (ID60).

Integrating multidisciplinary perspectives into this dialogue would significantly enhance the approach (methodological and communicational) towards such a complex field of research, which 27.9 % of respondents believed. Respondents also indicated a lack of multidisciplinarity, with a concurrent lack of transversal competencies and integrated solutions for multidimensional problems. Integrating multidisciplinary perspectives into this field would significantly enhance the approach towards such complex phenomena. Multidisciplinary in natural hazards means the following:

build and use land planning integrated multi-risks models which are able to contain both multi-hazard analyses (including hazards evolutions due to climate change) and complex exposure elements (including population migration, natech components) (ID33)

that “deal with the underlying conditions that influence (social and physical) vulnerability to natural hazards, namely, poverty and inequality” (ID37). This may be well explained by Diekman et al. (2015), who analysed women's motivation for undertaking a STEM career (for study or work). Collaborative goals, such as translating theory into practice to help communities advance and enhance development, traditionally appear to lack in the STEM fields. Inter- and transdisciplinary research may therefore be a women's professional requirement to be able to consider the multifaceted nature of the problem. However, although it is widely recognised, it is still very much concentrated within specific disciplinary areas (Latour, 2004). Datta (2018) also recognised the need to overcome dynamic notions of static disciplinary practice welcoming interdisciplinary research training to solve and understand the practical challenges from various perspectives. In this regard, we need to “step outside western norms” (ID27) and the influence that cultural and social relations and power may have on our approach to research:

I think that in natural hazards and Earth sciences, in general, we are suffering from a crisis of (lack of) diversity. I think there are many reasons for this. Some are historical, and we can hope that they begin to change as the conversation around diversity becomes more open [than it is now], but some are cultural. Academia does not always foster an environment where these open discussions can be had, and where people are held accountable for their actions (ID98).

Thus, a strong connection with collective and policy responsibility exists. Datta (2018) referred to indigenous knowledge. However, we believe we can expand the discourse to collaborative research knowledge that is culturally appropriate, respectful, honouring, and careful of the local community, promoting anti-racist, gender-inclusive theory and practice, cross-cultural research methodology, critical perspectives on environmental justice, and land-based education.

The call for a more inclusive and ethical science that is useful, usable, and used (Aitsi-Anselmi et al., 2018) is prominent among the respondents and ascribable to the progression of vulnerability investigated and underlined in the last decade of research in natural hazards and disaster management. Vulnerability but also the progression of vulnerability for multiple interactive factors is challenging for 16.4 % of respondents. A response recognised such “underlying conditions that influence the social and physical vulnerability of natural hazards, [are] poverty and inequality” (ID37). Women in disaster risk management are mostly “invisible and are not heard” (ID95), but also “women in science and leading positions are still a minority, and therefore their performance and opinions are also sometimes underestimated” (ID41) (see Sect. 2.2 and 2.3). Two respondents believe that the increased impacts of global warming and the concurrent increase in weather extremes can have an impact on the most vulnerable individuals globally, “seeing more [environmental] migration” (ID79) and “[…] lead[ing] to [a] reorganisation of populations” (ID80). However, despite the financial investments towards natural hazard mitigation infrastructures, there is much consensus that they are still not evenly distributed, “even within wealthy nations” (ID79). Adaptation, resilience, and sustainable solutions are challenging for the 18 % of respondents who reported significant obstacles in creating a culture of risk (by increasing awareness) because some natural hazards cannot be prevented, as they are natural geomorphic processes. It is “the human behaviour in responding to a natural disaster [that] can make the difference” (ID86). A respondent stated that it is a challenge to “address inequities for people in [the] location of hazards, access to mitigation/adaptation/preparation/recovery resources, access to hazard warnings, research/observing near underserved communities” (ID103); furthermore, “rather than the technological progress the biggest challenge is reducing the losses where resources are not available” (ID93). The last 13.1 % argue instead about the poor forecast of hazards, poor understanding of the complexity of the occurrence of phenomena and their effects, and lack of early warning systems.

2.2 Natural hazards and gender equity: challenges and solutions

Natural hazards affect individuals without fixed distinctions of their gender, and it is important to not over-generalise a popular trend that sees women as vulnerable per default. However, case-specific disaster losses demonstrate how women and girls are more likely to be disproportionately affected by disasters during and in the aftermath of disasters, a situation exacerbated by the increase in climate-change-induced hazardous events (Neumayer and Plümper, 2007; Fatouros and Capetola, 2021). The impact includes unprecedented challenges regarding health and well-being, for example, high rates of mortality and morbidity, prolonged psychological distress, and exposure to high-risk domestic environments (Fatouros and Capetola, 2021; Thurston et al., 2021)1, also hampering their opportunity to gainful employment after the occurrence of a disaster. Socio-economic conditions and cultural beliefs, social norms, and traditional practices contribute to the complex progression of the vulnerability of women in the wake of natural hazards and disasters, recognised by 12.3 % of respondents. Cultural, systemic inequalities emerge, especially in “lesser-developed countries, but almost everywhere [where] women are paid less and thus have less to respond to disasters” (ID45). In addition, it is more difficult for a female-headed household to acquire financial assistance and loans that are essential in the post-disaster rebuilding and re-establishing processes (Alagan and Aladuwaka, 2011; Fatouros and Capetola, 2021).

Systemic inequalities are also perceived at the family level, because as a respondent expressed, “women are less encouraged to take information on their own, in most cases, they listen to their partner and agree with their decisions” (ID82), which is not new in literature (Cvetković et al., 2018). Patriarchal families can experience communication problems within the domestic sphere and in the wake of natural hazard occurrences (Cvetković et al., 2018; Thurston et al., 2021). In this context, a respondent added,

the most obvious challenge is the need to find ways to give women a voice in some countries where, again, the society is male-dominated. Women will often be the people in the household responsible for preparedness and planning activities related to natural hazards. Yet, their opinion may not be sought when decision and policymakers put together plans for improving household resilience (ID109).

Another respondent, in fact, imperatively stated, “educat[e] women to react and survive. The experience of the Indian Ocean tsunami 2004 is that women died more than men because they waited at home for their husbands to leave their homes” (ID91). In practical terms, 18.9 % of the respondents asked for more awareness and support for educational and empowerment activities for women.

Women have unfortunately globally [fewer] opportunities for education and might therefore already be running behind in their understanding of natural hazards and how to prepare themselves and their communities. More effort should be done to reach female communities and educate them (ID104)

expressed a respondent sharing the concerns of many others, who additionally argue for “enhanc[ing] the connection of women in the field of natural hazards and make their voice heard” (ID19).

The concept of unheard voices is well experienced personally by most respondents and is found in Sect. 2.3. Awareness should not be considered just as a means but also as a place. We found an interesting comment of a respondent asking for “the creation of safe spaces to consider fully the impacts on women in the event of hazard events, and their experiences and frustrations as researchers” (ID27). This approach recognised the need for a horizontal space of dialogue in DRR, where no top-down or bottom-up approaches are considered. Women's accumulated skills, experiences, and capabilities in times of catastrophes are often not adequately identified, recognised, and promoted. Women's participation in DRR decision-making processes at all levels throughout the world is meagre. In this respect, 18 % of respondents perceive a lack of inclusivity (of minorities in general, thus extending the vulnerable pool) and potential differences related to gender in risk assessment (both research and practice). Inclusivity has been advocated to be “not just to reach a quota and not only if they first have to be more like the majority (e.g. men-like women, rich coloured people)” (ID36). Respondents share the concern that women and other gender minorities do not have a seat at the table when it comes to disaster risk management and resilience. Hence, their needs and interests are excluded from disaster management programmes (Dominey-Howes et al., 2014; Gaillard et al., 2017; Gorman-Murray et al., 2018), which fail to recognise their diverse economic, political, legal, occupational, familial, ideological, and cultural backgrounds (Zaidi and Fordham, 2021), creating many issues during response and recovery stages (Hemachandra et al., 2018; Thurston et al., 2021). However, women are considered agents of change with unique skills, qualities, and expertise benefitting quality governance (Gurmai, 2013) through accuracy and transparency in the decision-making process (Araujo and Tejedo-Romero, 2016). Gender inclusion in DRR is recognising and welcoming differences rather than accepting homogeneous thinking. Respondents' testimonies make us realise that the personal experiences in DRR research and management are well integrated into individuals' cognitive and experiential backgrounds. A total of 31 % of respondents argue for gender mainstreaming with leadership and inclusion in disaster management policies and practices. They recognise female underrepresentation in leadership positions and male dominance in decision-making bodies and communities related to the disaster cycle (18.9 %). A respondent is convinced that “better equity between genders in governing bodies would modify the decision trees of the authorities, particularly in terms of mitigation and long-term view pattern[s]” (ID33).

A total of 6.6 % of respondents to question Q2 believe that gender is not a (big) problem in natural hazards. Most of their responses refer to positive personal experience in their professional career and the opinion that “science is likely one of the field[s] that suffers least of gender un-equality. At least in the western countries.” (ID86). Interestingly, none of these eight respondents considered gender an important variable in the disaster assessment or its vulnerability construction. We discuss positive changes experienced by the respondents in terms of gender equity in the professional sphere more in Sect. 2.3.

All the above demonstrates a literature gap in identifying the ways to improve the role of women in disaster risk governance derived by a gender data gap that still exists. A total of 7 % of the respondents found it a priority to collect more disaggregated data to raise the visibility of the problem when assessing risks and adaptation options of natural hazards, recognising gender differences without mainstreaming the stereotypes. That might give the idea of gender to be merely connected to a vulnerable condition (Roder et al., 2017) and to be exclusively related to women, promoting stereotypical notions of women as “victims” or the “weaker sex” (Zaidi and Fordham, 2021). This is because, often, vulnerability assessments do not emphasise the fact that individuals simultaneously belong to multiple and intersectional social groups – gender being just one of these – from which they draw their identities and which shape their risk profile in the context of disasters (Zaidi and Fordham, 2021). Real progress towards mainstreaming gender into DRR needs a cultural change beyond gender stereotypes (13 % of responses). Possibly,

it would be great if there could be some overarching guiding principles that all institutions could adhere to, but academia is quite fragmented, so I think it really comes down to individual institutions fostering open conversations and using these to drive change (ID86).

Education is still considered at the base of the change, able “to build bridges [and] not barriers between each other and to see the richness in diversity and inclusivity” (ID112).

Finally, the need to include gender-specific response and recovery measures is an utmost priority for 4.1 % of respondents, where 0.8 % argue for a gendered and inclusive language and communication. So, combining multiple concepts brought up by the interviewees, we need women, and we need to use appropriate language when including them in the DRR policy and practice. However, which women should be involved? This is the interesting question that Enarson and Chakrabarti (2009) expressed in one of the latest books. They recognised the need to consult and involve local women's organisations and networks, including development and grassroots organisations active in high-risk areas.

We can conclude shortly that there is no “silver bullet” to solve gender equity in natural hazards. However, there is a need to know how useful and effective concrete examples, specific suggestions, action guides, and indicators are to mainstream gender into DRR.

2.3 Professional development and gender equity

The questions related to natural hazards and gender equity (Q2 and Q3) were perceived to be related to natural hazards per se (see Sect. 2.2) and for some others to professional development (Fig. 1, light grey boxes). Only Q4 specifically addressed gender-based issues in the work environment; in particular, we asked for personal experiences. Since personal experiences and general challenges often coincide, we have used both to address the abundant issues still residing within the community and the actions to be implemented for a more inclusive work environment. The challenges perceived in natural hazards and gender equity (Q2) are for 37.7 % of responses related to the lack of role models and female representation in decision roles and leadership positions, showing the range of career possibilities and paths. In addition, 36.1 % of respondents (Q2) evidenced unresolved challenges related to an unfair reward structure, pay gap, life–work imbalance, stereotyping, and lack of recognition in a male-dominated field. However, these are not just perceptions; they are also matched by 73.8 % of personal experiences (Q4), people who have confronted career advancement and unfair treatment obstacles.

In detail, 27.9 % experienced being attributed a lower salary compared to male colleagues and being discriminated against in obtaining leadership positions:

More visibility is given to male colleagues all the time. Even more power and resources are given to them. In my place of work (State organisation), power positions belong 100 % to men (ID17).

Moreover, 14.8 % of respondents also experienced or witnessed life–work imbalance, particularly worsened due to unequal expectations of women and men's family responsibilities. A respondent reported that “it has always been very difficult to combine motherhood with the challenges of making a career” (ID37), and another echoed that “it has been very hard to find role models in my field when I took the decision of having a family. I had no reference for a successful woman in my field with children” (ID69).

Unfair treatment has also been experienced widely by our respondents. A respondent reported “My opinions have been quite often undervalued by other colleagues. Even when I was the PI of a project, some people preferred to speak to male colleagues” (ID110). Compared to male colleagues, and a lack of credibility was reported by 27.9 %, a lack of respect regardless of role was reported by 23.8 %. Sexualisation and harassment were reported by 13.9 %. One of the interviewees, unfortunately, shared one of the most negative experiences:

Anything deemed “feminine” about me was used against me as a weakness. Constant inappropriate talk [was] designed to see if it would get a reaction out of me by my co[-]workers. In the field, free time was spent at the bar or even hostess lounges, and I was incredibly uncomfortable. Then I was put in a closed-door meeting with just my supervisor and asked how working there as a woman was. I felt very unsafe and therefore unable to be truthful (ID79).

Discrimination can be pervasive to the point of feeling “pushed to be more “masculine” in the workplace to fit in” (ID79). To our dismay, the biases and stereotypes reported and the harassment experienced are not new to women working in male-dominated disciplines or literature (Kenney et al., 2012), news outlets, and documentaries (Pottle et al., 2020). Despite the wide recognition of the problem, progress is still slow. Cultural, systemic inequities are part of this problem and are linked not only to gender stereotypes but also to age, ethnicity, religion, and nationality (9.8 % of respondents).

Finally, 8.2 % of respondents reported issues related to fieldwork: they experienced exclusion and lack of consideration of their specific needs precluding them from performing tasks. In some cases, the problem is again very much related to stereotypes concerning capability; one respondent reported, “Many times in the field I was asked, “are you sure you can do this (going uphill, going down, dirt myself)?” (ID44). One respondent also felt uneasy “about certain accommodations (e.g. bathroom) that I feel I might be imposing on my peers, and thinking twice about taking valuable measurements in areas where my safety might be at risk” (ID101).

A positive trend has been observed concerning structural changes in recent times. For example, one respondent who experienced discrimination in the past recognised that “female colleagues entering the field now, with solid competencies and a lot of “guts”, have much more chances now to move up to decision positions” (ID23). In addition, 23 % of respondents explicitly said they did not experience any gender-related career challenges, reporting their positive experience in a supportive environment and gender-mixed teams (at both the educational and the professional levels). Although for a couple of respondents the personal experience was positive, they reported being aware of gender-related challenges encountered by other female colleagues.

We can conclude that the struggle for women to find inclusive work environments was and still is not resolved, despite recognising positive efforts in the right direction and some virtuous examples. Solutions concerned with promoting gender equity in the work environment are envisioned by 54.1 % of the responses to Q3. The proposed solutions will not read unfamiliar to those accustomed to the debate in the broader gender-related STEM career challenges: “Diversity begins at the top. Work to understand why retention is challenging and change reward structures. Put women in leadership positions. Refuse to hold all-male panels, all-male sessions, all-male anything” (ID42), said one respondent, well summarising the general feeling of the interviewees.

A total of 43.9 % of responses suggested enhancing selection transparency via providing equal support and access to resources and information, recognising women's work, and changing the reward structure, ensuring an experience-based salary to close the gender gap. Bell and co-authors advocated for such changes and actions almost 20 years ago (Bell et al., 2003). It is noteworthy and disappointing how slow the process towards equity is if we are still discussing the benefit these changes would accomplish today. Indeed, many institutions have taken steps forward in these regards. However, the mission is far from being complete, and possibly one reason is that the efficacy of actions undertaken is often not measured or not publicly shared (Timmers et al., 2010; McKinnon, 2020). Promoting women's work reflected 31.8 % of responses calling for hiring more women, particularly in high-profile and relevant positions, as a solution. To achieve that, quotas are one of the actions commonly proposed. Quotas have long since been introduced in many institutes and funding organisations and resulted in an effective reduction of the gender gap in leadership roles in certain areas (Handley et al., 2020; Pellegrino et al., 2020). However, as some respondents also noted, quota rules may appear only on paper at times. They may also be seen as controversial or counterproductive, reinforcing old stereotypes (Handley et al., 2020; Pellegrino et al., 2020). We believe that quotas can be a double-edged sword able to raise negative opinions among women in the workplace, undermining their credibility. However, quotas can be a valuable instrument to promote and normalise more gender-balanced environments until more transparency in selection procedures is enacted.

One respondent, for example, pointed out

as a woman, I am always extremely disappointed when positions are open only for my gender. First, because it means that male[s] in this specific institution had the power to only employ other males. Second, because women employed at such positions can always be taught that they only got it because of their gender, not their capacities (ID12).

A global survey targeting Earth and space scientists by Popp et al. (2019) clearly showed the divided opinion on quotas. They noted how quotas' favour tends to be gendered, with 44.9 % of women and 27.9 % of men sharing a favourable opinion, and related to career stage. Among women favouring quotas, 56.1 % are postdocs, while among men 34 % hold a professor position. They concluded this result showed a clear sign of a disadvantage for early- to mid-career women and a fear of being negatively affected by quotas for mid-career men geoscientists (Popp et al., 2019). Handley et al. (2020) have analysed the gender balance in universities in Australasia and noted that even if quota regulations were in place, few to no women would apply to vacancies for various reasons. Therefore, to counteract the issue, they proposed creating a database of female professionals working in geosciences divided by area of research. Such a database can be used to find new collaborators, advertise vacancies, invite applications from relevant candidates (possibly leading to a larger number of female applicants), inquire about consultancy, ask for an interview, and pool for surveys. We find this solution interesting and responsive to the needs of giving equal career opportunities while maintaining a transparent process and recognising female professionals. Such a database could also be used to promote female-specific mentorship and role models, including increasing the visibility of women's work and thus help engage more female students and potentially retain them in the field, as noted by 27.8 % of responses. On mentoring and role models, Handley et al. (2020) highlighted an important point. Since not many women occupy apical positions yet, horizontal mentoring among women peers or close in the career stage can also be a good option. For several years, several associations have made their primary goal to provide support and mentoring to women in geosciences. These include the Earth Science Women's Network (ESWN; Adams et al., 2016) established in 2016 by 500 women scientists and Geolatinas founded in 2002. A complete list of women-focused and women-led geoscience and related networks are available in Handley et al. (2020). Moreover, female-specific funding and support schemes, including those specifically for supporting motherhood, are solutions for 21.2 % of respondents. The latter goes together with the promotion of life–work balance, the acceptance of part-time careers, and a better redistribution of roles and responsibilities, which are seen as significant help by 13.6 % of responses. In addition to promoting more women in our work environments and providing adequate support, institutions must become safe places where people in “positions of power and administration take harassment claims seriously and stand by a zero-tolerance policy and made women feel comfortable and believed when reporting these issues” (ID80), said a respondent, reflecting 15.2 % of responses.

We can conclude that one of the main steps forward with the potential to have a profound impact is a broad cultural change that will break down stereotypes and allow real diversity. A total of 27.8 % of responses explicitly hope for this change in the work environment, but it is possible to include all actions proposed in this much broader resolution. Cultural changes are slow to achieve. Keeping up a constructive debate and attention around the topic helps as much as the proposed change in the reward structure, the promotion of women's work, hiring more competent women for apical positions, providing motherhood-specific support, and redefining roles and responsibilities. We do not exclude the immense necessity for normalisation of co-parenting and genderless or gender equivalent parental initiatives. We believe that there have been very prominent actions undertaken in this direction in some countries. However, they are political regulations where we, singularly, have little to no control. Instead, institutions (or companies) can lead the change and become the first promoters of equal support with well-thought-out plans and effective assessment.

One more way to foster profound changes is to promote inclusive language at all levels, particularly from people in leadership positions, regardless of their gender. Language profoundly shapes our mind and our way of interpreting the world we live in: the words we use can discriminate as much as they can empower (McKay et al., 2015; Taheri, 2020). Where not yet in place, specific training on inclusive language and unconscious bias should be organised at institutions and organisations and possibly be made mandatory with a top-down priority.

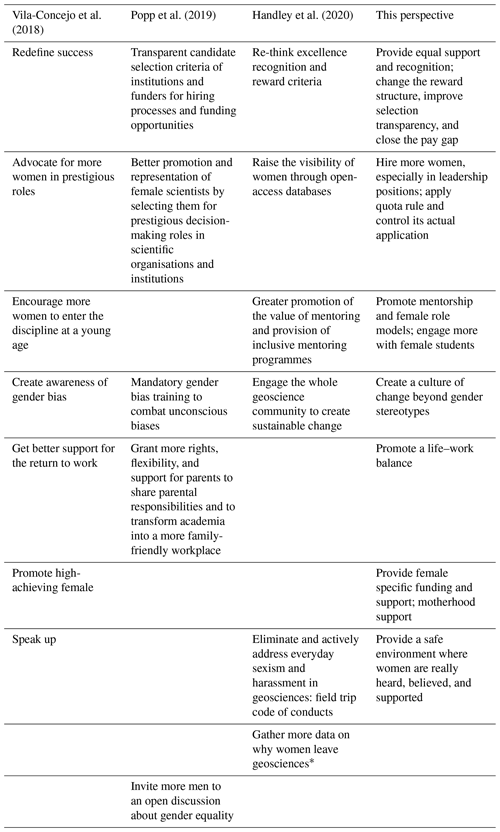

Table 2Summary of strategies and envisioned solutions towards gender equity in STEM and geoscience from recent literature and this study. It can be observed how the proposed solutions align well among themselves, showing strong similarity. When a solution has been proposed that does not find direct comparison, the related box is left blank. * Handley et al. (2020) focus mainly on the Australasian situation. However, these data are also fundamental for elsewhere in the world.

The solutions envisioned by the pool of respondents to our survey are very similar to strategies already highlighted in the literature, reported in Table 2. We can conclude that strategies, actions, and solutions are well defined and, in some instances, already enacted. However, monitoring the efficacy of these actions is far more complex but of great relevance to understanding which of them are worth pursuing and which instead do not provide significant improvement towards closing gender-based issues. Timmers et al. (2010), analysing aggregated data for employment in the year 2000–2007 in 14 universities in the Netherlands, could observe that the larger the number of gender equality policy actions adopted, the more significant the reduction of the glass ceiling. However, they criticised the lack of internal evaluation of the adopted measures by the universities themselves. Universities, research institutes, and organisations should promote researching and applying adequate methods for monitoring their strategies and implementing them with high priority.

From the response analysis and state-of-the-art literature, we have understood that gender-based challenges at the professional level and within the disaster cycle are very close. Moreover, because of their interrelation, the solutions proposed may not be exclusive for a professional or a more technical sphere, but they can work simultaneously, with mutual benefit. Early education is key to fostering a cultural revolution. If children attend classes related to social norms, diversity, and inclusion, they might become adults able to see beyond individuals' gender. If so, women and other gender minorities would be much more considered for leadership positions in DRR institutions or academia, thus promoting a more comprehensive vision about vulnerabilities before, during, and after natural hazard occurrence. But the cultural change must also be vertical in a top-down approach by organising specific compulsory training for leaders and professionals to explain biases and stereotypes and fight them to promote a more effective and just natural hazard management and, thus, more inclusive society. In addition, the scale of the change should consider the horizontal space in which role models are found within peer networks to promote and support positive imitative behaviour.

For what concerns the guiding principles and institutions, several examples highlighted in this perspective showed how the political agenda (e.g. SFDRR) lacks any gender-related practical guidance. The same is true for all other local administrations and institutions. Many gender-inclusive initiatives are short-term and aim primarily to spark interest rather than build skills. Most of the time, they are just a box “ticked” rather than an effective action. Therefore, we advocate for compulsory study, implementation, and application of methods to measure and monitor the efficacy of actions and strategies put in place at institutional, national, and international levels over time.

In addition, current gender-inclusive initiatives exclude men despite literature demonstrating a disjunction between the assumptions and lack of understanding of the reality of men's lived disaster experiences (e.g. Rushton et al., 2020). What Fordham and Meyreles (2014) called a paradox, masculinity, which contributes to the structure of power that privileges men, can also put men at risk (e.g. Jonkman and Kelman, 2005; Ashley and Ashley, 2008; Fitzgerald et al., 2010). Similarly, we can observe how in the professional domain, specific jobs and disciplines are still perceived as belonging to a (stereotyped) female world only and where men are seen as outliers. If the final goal is a truly inclusive society, we must be aware of all the biases and stereotypes we are surrounded by and counteract all of them appropriately. The future of research in natural hazards and disaster mitigation and our professional domain needs to include all voices and find allies in the privileged categories of the specific domain of interest. We think that lessons learnt within the context of discrimination against women can serve as a starting point to expand the discourse to other gender minorities and that intersectional research should be advocated for to gain an all-inclusive approach and understanding of disaster stories that foreground differences.

Given the confidential nature of data gathered from the interviews, they are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding authors.

The supplement related to this article is available online at: https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-22-85-2022-supplement.

All authors have contributed to the conceptualization and data curation. VC and GR have equally contributed to the analysis and preparation of the first draft. All authors have contributed to the revision and editing of the manuscript.

At least one of the (co-)authors is a member of the editorial board of Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the special issue “Perspectives on challenges and step changes for addressing natural hazards”. It is not associated with a conference.

We would like to thank the Copernicus NHESS office team for their help in distributing the survey and especially the survey participants, who took the time to share their thoughts and experiences.

This paper was edited by Paolo Tarolli and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Adams, A. S., Steiner, A. L., and Wiedinmyer, C.: The earth science women's network (ESWN): Community-driven mentoring for women in the atmospheric sciences, B. Am. Meteorol. Soc., 97, 345–354, https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-15-00040.1, 2016.

Aitsi-Selmi, A., Blanchard, K., and Murray, V.: Ensuring science is useful, usable and used in global disaster risk reduction and sustainable development: A view through the Sendai framework lens, Palgrave Commun., 2, 1–9, https://doi.org/10.1057/palcomms.2016.16, 2016.

Alagan, R. and Aladuwaka, S.: Natural disaster, gender, and challenges: Lessons from Asian tsunami, Res. Polit. Sociol., 19, 121–132, https://doi.org/10.1108/S0895-9935(2011)0000019012, 2011.

Alon, T., Doepke, M., Olmstead-Rumsey, J., and Tertilt, M.: The Impact of COVID-19 on Gender Equality, NBER Working Paper No. 26947, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA, available at: https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w26947/w26947.pdf (last access: 14 January 2022), 2020.

Araujo, J. F. F. E. and Tejedo-Romero, F.: Women's political representation and transparency in local governance, Local Gov. Stud., 42, 885–906, https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2016.1194266, 2016.

Ashley, S. T. and Ashley, W. S.: Flood fatalities in the United States, J. Appl. Meteorol. Clim., 47, 805–818, https://doi.org/10.1175/2007JAMC1611.1, 2008.

Bell, R. E., Kastens, K. A., Cane, M., Muller, R. B., Mutter, J. C., and Pfirman, S.: Righting the balance: Gender diversity in the geosciences, Eos Trans. Am. Geophys. Union, 84, 292, https://doi.org/10.1029/2003EO310005, 2003.

Chandler, R., Guillaume, D., Parker, A. G., Mack, A., Hamilton, J., Dorsey, J., and Hernandez, N. D.: The impact of COVID-19 among Black women: evaluating perspectives and sources of information, Ethn. Health, 26, 80–93, https://doi.org/10.1080/13557858.2020.1841120, 2021.

Cvetković, V. M., Roder, G., Öcal, A., Tarolli, P., and Dragićević, S.: The role of gender in preparedness and response behaviors towards flood risk in Serbia, Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health, 15, 2761, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15122761, 2018.

Datta, R.: Decolonizing both researcher and research and its effectiveness in Indigenous research, Res. Ethics, 14, 1–24, https://doi.org/10.1177/1747016117733296, 2018.

De Silva, K and Jayathilaka, R.: Gender in the context of Disaster Risk Reduction; A Case Study of a Flood Risk Reduction Project in the Gampaha District in Sri Lanka, Procedia Econ. Financ., 18, 873–881, https://doi.org/10.1016/S2212-5671(14)01013-2, 2014.

Diekman, A. B., Weisgram, E. S., and Belanger, A. L.: New Routes to Recruiting and Retaining Women in STEM: Policy Implications of a Communal Goal Congruity Perspective, Soc. Issue. Policy Rev., 9, 52–88, https://doi.org/10.1111/sipr.12010, 2015.

Dominey-Howes, D., Gorman-Murray, A., and McKinnon, S.: Queering disasters: on the need to account for LGBTI experiences in natural disaster contexts, Gender Place Cult., 21, 905–918, https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2013.802673, 2014.

Enarson, E. and Chakrabarti, P. G. D.: Published version in Women, in: Gender and Disaster: Global Issues and Initiatives, edited by: Enarson, E. and Dhar Chakrabarti, P. G., Sage, 1–23, ISBN 13: 9788132101482, 2009.

Fatouros, S. and Capetola, T.: Examining Gendered Expectations on Women's Vulnerability to Natural Hazards in Low to Middle Income Countries: A critical Literature Review, Int. J. Disast. Risk Reduct., 64, 102495, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2021.102495, 2021.

Finucane, M. L., Slovic, P., Mertz, C. K., Flynn, J., and Satterfield, T. A.: Gender, race, and perceived risk: The “white male” effect, Health. Risk Soc., 2, 159–172, https://doi.org/10.1080/713670162, 2000.

Fitzgerald, G., Du, W., Jamal, A., Clark, M., and Hou, X. Y.: Flood fatalities in contemporary Australia (1997–2008): Disaster medicine, EMA – Emergency Medicine Australasia, 22, 180–186, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-6723.2010.01284.x, 2010.

Fordham, M. and Meyreles, L.: Gender aspects of disaster management, in: Disaster Management: International Lessons in Risk Reduction, Response and Recovery, edited by: Lopez-Carresi, A., Fordham, M., Wisner, B., Kelman, I., and Gaillard, C., Routledge, 23–40, ISBN 978-1849713474, 2014.

Gaillard, J. C., Gorman-Murray, A., and Fordham, M.: Sexual and gender minorities in disaster, Gender Place Cult., 24, 18–26, https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2016.1263438, 2017.

Gonzales, L.: Participation of Women in the Geoscience, AGI Data Br. 2019-015(November), 1–2, available at: https://www.americangeosciences.org/geoscience-currents/participation-women-geoscience-profession (last access: 14 January 2022), 2019.

Gorman-Murray, A., McKinnon, S., Dominey-Howes, D., Nash, C. J., and Bolton, R.: Listening and learning: giving voice to trans experiences of disasters, Gender Place Cult., 25, 166–187, https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2017.1334632, 2018.

Gurmai, Z.: Women's role in good governance Workshop of the CEE Network for Gender Issues, 14–15, available at: https://www.europeanforum.net/uploads/2013_cee_booklet_en_a5_v4.pdf (last access: 14 January 2022), 2013.

Handley, H. K., Hillman, J., Finch, M., Ubide, T., Kachovich, S., McLaren, S., Petts, A., Purandare, J., Foote, A., and Tiddy, C.: In Australasia, gender is still on the agenda in geosciences, Adv. Geosci., 53, 205–226, https://doi.org/10.5194/adgeo-53-205-2020, 2020.

Hemachandra, K., Amaratunga, D., and Haigh, R.: Role of women in disaster risk governance, Procedia Eng., 212, 1187–1194, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2018.01.153, 2018.

Jonkman, S. N. and Kelman, I.: An analysis of the causes and circumstances of flood disaster deaths, Disasters, 29, 75–97, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0361-3666.2005.00275.x, 2005.

Kenney, L., McGee, P., and Bhatnagar, K.: Different, not deficient: The Challenges Women Face in STEM Fields, J. Technol. Manage. Appl. Eng., 28, available at: https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.atmae.org/resource/resmgr/Articles/Kenney-Challenges-Women-STEM.pdf (last access: 14 January 2022), 2012.

Latour, B.: Politics of Nature: How to bring the science into democracy, edited by: Porter, C., Harvard University Press, London, UK, ISBN 9780674013476, 2004.

McKay, K., Wark, S., Mapedzahama, V., Dune, T., Rahman, S., and MacPhail, C.: Sticks and stones: How words and language impact upon social inclusion, J. Soc. Incl., 6, 146, https://doi.org/10.36251/josi.96, 2015.

McKinnon, M.: The absence of evidence of the effectiveness of Australian gender equity in STEM initiatives, Aust. J. Soc. Issue., https://doi.org/10.1002/ajs4.142, 2020.

Mondino, E., Scolobig, A., Borga, M., and Di Baldassarre, G.: Longitudinal survey data for diversifying temporal dynamics in flood risk modelling, Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci., 21, 2811–2828, https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-21-2811-2021, 2021.

Neumayer, E. and Plümper, T.: The gendered nature of natural disasters: The impact of catastrophic events on the gender gap in life Expectancy, 1981–2002, Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr., 97, 551–566, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8306.2007.00563.x, 2007.

Paradise, T. R.: Perception of earthquake risk in Agadir, Morocco: A case study from a Muslim community, Environ. Hazards, 6, 167–180, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hazards.2006.06.002, 2005.

Pellegrino, A., Zucchelli, M., Angeletti, F., Russo, A., Gloder, A., Pancalli, M. G., Vestito, E., Yamazaki, N., Kawashima, R., Otsuka, A., Ismail, N., Nassisi, A., Valente, C., Battagliere, M. L., and Buongiorno, M. F.: Cross-cultural analysis on the gender equality perception as a driver for the future space workforce development, in: Proc. Int. Astronaut. Congr. IAC, 71st International Astronautical Congress – The CyberSpace Edition: IAC-2020, Virtual format, October 2020, 12–14, 2020.

Popp, A. L., Lutz, S. R., Khatami, S., Emmerik, T. H. M., and Knoben, W. J. M.: A Global Survey on the Perceptions and Impacts of Gender Inequality in the Earth and Space Sciences, Earth Space Sci., 6, 1460–1468, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019EA000706, 2019.

Pottle, M., Cheney, I., Shattuck, S., Cheney, I., Shattuck, S., Hopkins, N., Burks, R., and Willenbring, J.: Picture a Scientist, an Uprising Production, available at: https://www.pictureascientist.com/ (last access: 14 January 2022), 2020.

Risman, B. J.: Gender as a Social Structure, in Handbook of the Sociology of Gender, edited by: Risman, B. J., Froyum, C. M., and Scarborough, W. J., Springer International Publishing, Cham, 19–43, https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243204265349, 2018.

Roder, G., Sofia, G., Wu, Z., and Tarolli, P.: Assessment of Social Vulnerability to Floods in the Floodplain of Northern Italy, Weather Clim. Soc., 9, 717–737, https://doi.org/10.1175/WCAS-D-16-0090.1, 2017.

Rushton, A., Phibbs, S., Kenney, C., and Anderson, C.: The gendered body politic in disaster policy and practice, Int. J. Disast. Risk Reduct., 47, 101648, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101648, 2020.

Taheri, P.: Using Inclusive Language in the Applied-Science Academic Environments, Tech. Soc. Sci. J., 9, 151–162, https://doi.org/10.47577/tssj.v9i1.1082, 2020.

Thurston, A. M., Stöckl, H., and Ranganathan, M.: Natural hazards, disasters and violence against women and girls: A global mixed-methods systematic review, BMJ Global Health, 6, 1–21, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2020-004377, 2021.

Timmers, T. M., Willemsen, T. M., and Tijdens, K. G.: Gender diversity policies in universities: A multi-perspective framework of policy measures, High. Educ., 59, 719–735, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-009-9276-z, 2010.

UNESCO: UNESCO science report: towards 2030, in: Second revised edition 2016, edited by: Schlegel, F., UNESCO, France, available at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000235406 (last access: 14 January 2022), 2015.

Vila-Concejo, A., Gallop, S. L., Hamylton, S. M., Esteves, L. S., Bryan, K. R., Delgado-Fernandez, I., Guisado-Pintado, E., Joshi, S., Da Silva, G. M., De Alegria-Arzaburu, A. R., Power, H. E., Senechal, N., and Splinter, K.: Steps to improve gender diversity in coastal geoscience and engineering, Palgrave Commun., 4, 103, https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-018-0154-0, 2018.

Wartman, J., Berman, J. W., Bostrom, A., Miles, S., Olsen, M., Gurley, K., Irish, J., Lowes, L., Tanner, T., Dafni, J., Grilliot, M., Lyda, A., and Peltier, J.: Research Needs, Challenges, and Strategic Approaches for Natural Hazards and Disaster Reconnaissance, Front. Built Environ., 6, 1–17, https://doi.org/10.3389/fbuil.2020.573068, 2020.

WEF – World Economic Forum: Global gender gap report 2021, The World Economic Forum, available at: https://www.weforum.org/reports/global-gender-gap-report-2021 (last access: 14 January 2022), 2021.

Yildirim, T. M. and Eslen-Ziya, H.: The differential impact of COVID-19 on the work conditions of women and men academics during the lockdown, Gender Work Organ., 28, 243–249, https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12529, 2021.

Zaidi, R. Z. and Fordham, M.: The missing half of the Sendai framework: Gender and women in the implementation of global disaster risk reduction policy, Prog. Disast. Sci., 10, 100170, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pdisas.2021.100170, 2021.

Disclaimer: the topic of well-being, gender, and natural hazards related to psychological and physical burdens (e.g. violence or suicide in the aftermath of a disastrous event) has not been included in the current paper because of the lacking competencies to develop such complex clinical topic. In addition, none of the respondents considered this topic in their answers.