the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Tracing the evolving actor network: a social network analysis of the 2018 Mayotte crisis in the press

Louise Le Vagueresse

Marion Le Texier

Maud Helene Devès

The media, especially the press, play a crucial role in shaping public understanding during risk and crisis management, acting as intermediaries between various actors and the public. However, their framing of sources can introduce biases into these representations. Limited analysis exists regarding how press coverage portrays relationships between crisis and risk management actors. Using social network analysis, this study maps quotation networks in press coverage of a seismo-volcanic crisis in Mayotte, a French overseas department. This approach allows for an overview of the relationships between actors, highlights unique aspects related to the context and media portrayal, reveals underlying representations and levels of trust among interviewed actors, and visualises the network's dynamics over time. Analysis revealed variations in narrative approaches among newspapers, with some focusing on specific aspects. The results show that national authorities received more attention than local elected representatives and that scientific figures dominated reported speech, while the population's perspective remained relatively passive despite its centrality to the quotation network. Prominent individuals held significant positions, emphasising the importance of personal connections in communication and revealing a potential distrust of political and scientific institutions. This finding underscores the need for greater proximity between information sources and the affected community.

- Article

(6207 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(548 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Risk communication is a key component of disaster risk reduction (UNISDR, 2015). Implementing an effective risk communication strategy is, however, not a trivial matter and presents a complex undertaking (e.g. Mileti and Sorensen, 1990; Tierney et al., 2001; Graham et al., 2022). There are many pitfalls at multiple stages: in the communication process between actors responsible for risk monitoring and management, as well as in the process of public information dissemination. It is particularly difficult when uncertainties are high, which is often the case in crises related to volcanic hazards for instance (e.g. Barclay et al., 2008; Solana et al., 2017; Andreastuti et al., 2019). Mass media (newspapers, television, radio) play an important role in shaping public information (see Perry and Lindell, 1989, pp. 47–62, or Scanlon, 2007, for an overview). In crisis situations, they are identified as the main source of information for the public actively seeking hazard-related information (Nazari, 2011 ; Poudel et al., 2015; Van Belle, 2015). This is especially true for local and national media (Allan et al., 2000; Scanlon, 2007; Jin et al., 2025), and their participation is thus crucial for effective warning dissemination (Lindell et al., 2006). News reports are also closely followed by crisis management teams, which in turn influences official communication strategies (e.g. Lagadec, 1991; Lindell et al., 2006). In the long term, they affect risk perception, notably by contributing to the circulation of “erroneous representations” of how individuals, groups, or organisations behave during disasters (Coleman, 1993; Quarantelli, 2002; Wachinger et al., 2013; Van Belle, 2015).

Compared to other sources, newspapers, especially the daily press, are commonly seen as a more credible source of information because of their ability to provide in-depth analytic coverage (Quarantelli, 2002, cited in Steelman et al., 2015). They are also widely relayed in other media or on social networks. The local press occupies a specific position in this respect, as local journalists are both interested parties and commentators on ongoing crises. The resulting coverage tends to be more regular and more detailed, and it often provides the raw material for press agencies and, through them, for other media (e.g. Nielsen, 2015; Cagé et al., 2017). Studies have also demonstrated the pivotal role played by local journalists as intermediaries between risk management authorities and populations when disseminating warning messages, conveying the community's concerns, and providing updates on the situation at the grassroots level (Scanlon, 2007). Newspapers' coverage constitutes, therefore, an important issue for disaster research (see Harris et al., 2012; Camilleri et al., 2020; Calabrò et al., 2020; Le Texier et al., 2016; Devès et al., 2019, 2022b).

However, the daily press, and the media in general, cannot be considered simple vehicles for providing information. As recalled by Aylesworth-Spink (2017), they act as “a complex mediator with specific interests and motivations”. The way the media depict an event is neither exhaustive nor neutral. There are many factors influencing the final coverage: selection of topics (Pavelka, 2014), layout and design choices (e.g. Moirand, 2006; Schindler et al., 2017; Billard and Moran, 2023), political ideology and editorial policy of the newspaper (e.g. Shoemaker and Reese, 1996; Kaiser and Kleinen-von Königslöw, 2019), access to sources and their respective social status (Ploughman, 1997), and choices of contextualisation (Llasat et al., 2009; Cavaca et al., 2016; Carter and Kenney, 2018). Day-to-day journalistic practices also play a role (e.g. Boykoff and Boykoff, 2004). The way journalists tend to juxtapose the accounts of heterogeneous sources, while important for depicting a variety of viewpoints, has been shown to “blur” messages (e.g. Lejeune, 2005; Léglise and Garric, 2012; Devès et al., 2022a), thereby reducing their clarity. These various factors can lead to conveying representations to the public that are sometimes very different from how authorities and scientists see the situation (Ploughman, 1995). They may also implicitly replicate common misconceptions (see Quarantelli, 1996) or reproduce asymmetrical power relationships between actors without questioning them (Valencio and Valencio, 2018; Devès et al., 2023).

Examining press coverage provides insights into the pivotal moments and key actors perceived by journalists covering the event, who often serve as primary observers on the scene. The use of content and thematic analyses allows for the reconstruction of the sequence of events, the mapping of actors' networks (Hijmans, 1996), and the identification of representations conveyed by the press toward at-risk communities. This is exemplified by studies like those conducted by Thistlethwaite and Henstra (2019) or Calabro et al. (2020). However, a limited number of studies analyse how relationships between actors are portrayed in the press. Do these networks of interrelations, commonly connecting crisis management actors, experts, and populations, align with the envisaged distribution of roles during crisis management planning? If disparities exist, what insights do they provide?

Examining such interrelations can be accomplished by creating maps of quotation networks, representing how actors cite or reference each other in the press text (McLaren and Bruner, 2022). This method falls within social network analysis (SNA), a widely employed approach in the social and information sciences (Otte and Rousseau, 2002; Sapountzi and Psannis, 2018). SNA utilises tools from network analysis and graph theory to investigate social structures and information circulation within networks of actors. Past studies utilising SNA or its derivatives in the realm of disaster risk research have focused on examining misinformation and the structuring of information networks on social media (e.g. Pourebrahim et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2018) or conducting a functional analysis of crisis management organisations (e.g. Trias et al., 2019; Flecha et al., 2023). To our knowledge, there is a lack of studies utilising SNA on press data within the context of risk or crisis management. Yet, this is an important area of research, as the approach allows for (i) gaining insights into the actual organisation of actors by providing a comprehensive view of all cited actors and their interactions, allowing the detection of communities (e.g. Park et al., 2015; Williams et al., 2015); (ii) identifying actors who are prominently featured, whether due to their perceived reliability, relevance in transmitting information on a subject, specific social role, or accessibility to journalists; (iii) examining the involvement of various actors and the evolution of this network over time; and (iv) accessing a particular representation of actors, whether active or passive in media coverage.

In this article, this mapping of quotation network method is applied to press coverage of a seismo-volcanic crisis which began in May 2018 in the French overseas department of Mayotte. This study builds upon two previous investigations. The first, by Devès et al. (2022a), focused on public information processes and identified shortcomings in both scientific and state institutional communication. The second, by Devès et al. (2023), illustrated how newspapers implicitly reproduce asymmetrical power relationships between actors (e.g. local versus national authorities, experts versus lay public). Building on these findings and using SNA methodology, this study aims to identify and compare the presence of actors according to their role in the risk reduction network, the geographical scope of newspapers (local versus regional versus national), and whether there are significant differences between newspapers.

Before presenting the selection of articles (Sect. 3.1) and methods (Sect. 3.2), Mayotte's geological and sociological contexts are briefly outlined, along with an explanation of why it constitutes an interesting case study (Sect. 2). The results are then presented (Sect. 4). Section 4.1 concentrates on the actors' mention frequency and form in varying newspapers. Section 4.2 focuses on whether actors' statements are displayed directly or through a third party. Section 4.3 explores the positions of the actors mentioned in the chain of quotation. Section 4.4 compares the actor network structures during several specific “moments” of this media coverage. Section 5.1 and 5.2 discuss differences between the press representation of the actor network and the official organisation of risk and crisis management in France and its overseas territories. Finally, Sect. 6 concludes on the value and limitations of this approach and on future avenues of research.

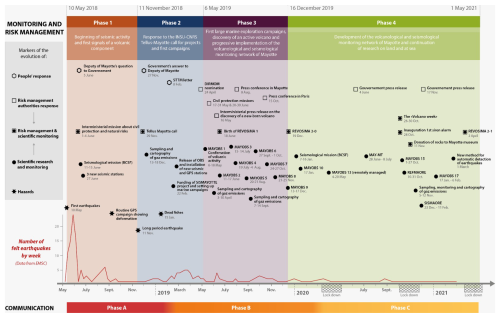

Devès et al. (2022a) provide a detailed description of Mayotte's geological context and the so-called “seismo-volcanic crisis” that began in Mayotte in May 2018. This section summarises the main events and reviews the latest scientific updates, since knowledge in this area evolves quite rapidly due to ongoing, significant research efforts. A detailed chronology is provided in Fig. 1.

Figure 1Key phases and milestones in the response by local and national authorities responsible for risk and crisis management, as well as by scientific experts monitoring seismo-volcanic activity in Mayotte. The period covered in this study spans 10 May 2018 to 1 April 2021. SISMAYOTTE, REFMAORE, MAY-MT, and SISMAORE refer to scientific campaigns – SISMAYOTTE was funded by Tellus Mayotte, while the others were supported by REVOSIMA's institutional partners. The lockdown periods indicated correspond to those implemented in metropolitan France during the Covid-19 pandemic (most scientific institutions involved in the monitoring effort are based in metropolitan France). Notably, Mayotte experienced longer lockdowns in spring 2020 and 2021, but no formal lockdown was imposed during autumn 2020 (figure from Devès et al., 2022).

The seismo-volcanic crisis began on 10 May 2018 with unusual seismic activity (tens of felt earthquakes in the first month alone, with a magnitude up to Mw 5.9; see Sira et al., 2018). This seismic crisis was linked to the formation of a new submarine eruption site, named Fani Maore, which was discovered 1 year later, in May 2019 (Feuillet et al., 2021), about 50 km off the eastern coast of the Mayotte islands. From a scientific perspective, uncertainties were exceptionally high, especially in the first months of the seismic crisis, due to scarce knowledge of the geodynamical context in the area and a poor monitoring network (Saurel et al., 2021; Bertil et al., 2021; Feuillet et al., 2021). The recorded signals were poorly constrained in terms of location and magnitude and remained difficult to explain in this region. The volcanic hypothesis to explain the origin of the seismic activity did not emerge until several months later, in October 2018, and was not confirmed until May 2019. This made public communication particularly difficult and led to the development of a “technicalist bias”, with frequent but minimalist communication from institutions that did little to help the population gain situational awareness (Devès et al., 2022a). Indeed, there was an overall feeling of a “lack of information” (Fallou et al., 2020), which led to the spread of numerous rumours to explain this phenomenon and to regular complaints from inhabitants and their representatives (see for instance the questions addressed to the government by a Member of Parliament for Mayotte, Ali, in 2018, as well as the open letter sent to the authorities and scientists by a group of citizens in February 2019; Picard, 2019). At the time of writing, the eruption of the new submarine volcano Fani Maore has ceased, and seismic activity is divided into two main clusters that have been active since the end of June 2018 (according to Lemoine et al., 2020), 5–15 km and 30–40 km from the coast (Feuillet et al., 2021; Saurel et al., 2021; Lavayssière and Retailleau, 2021). Most of these events are volcano-tectonic earthquakes. Another sign of this still-ongoing activity is the detection of acoustic plumes associated with geochemical anomalies 10–15 km off the coast (22 sites observed in July 2022, MAYOBS 23). These acoustic plumes are possibly linked to gas emissions monitored prior to 2018 on Petite Terre, Mayotte's second-largest island, east of the largest island and closer to the Fani Maore volcano. Hence, magmatic processes related to these observables are still located close to the island. As their uncertain evolution presents a significant hazard, this activity is currently being monitored by the Mayotte Volcanological and Seismological Monitoring Network (REVOSIMA).

In addition to scientific uncertainties and the ensuing difficulties in public information, other factors could also have undermined the relationship between actors. For instance, there is both a geographical and a cultural gap between the scientists involved and the local populations, since most of the former are based either in mainland France or on La Réunion and do not have many occasions to interact with Mayotte's inhabitants. As detailed in Devès et al. (2022a), Mayotte is a multicultural archipelago with a dominant oral culture where about 37 % of the population does not speak French (INSEE, 2017), which complicates risk communication from scientific institutions and the authorities in charge. It is also a particularly vulnerable territory marked by poverty and important social inequalities (Roinsard, 2014; INSEE, 2021). Since its recent departmentalisation in 2011, it has been regularly shaken by social crises, one ending just as the seismic swarm began (Roinsard, 2019; Mori, 2021). Finally, there seemed to be no living memory of seismic and volcanic phenomena in Mayotte within the population. The last important earthquake was a magnitude ML 5.3 event in 1993 (Bertil et al., 2021). This, added to the underwater nature of this activity, caused confusion among inhabitants. Some of them went so far as to doubt the scientific explanations and the very existence of a volcano, even today (see testimonials in Devès et al., 2023). In this context, marked by considerable scientific uncertainties, social tensions, and the involvement of a multitude of actors, particular attention is given to identifying the obstacles and mechanisms that have hampered information flow at each link of the communication chain.

Mayotte's seismo-volcanic activity is a useful case study because (i) although the seismic-volcanic phenomenon itself has been associated with moderate impacts, in the first years of activity, it triggered a social crisis that risk managers themselves qualified as a “communication crisis” (see questions to the government, Ali, 2018, where Deputy Ramlati Ali expressed a need for information in the national assembly, and an open letter sent by a citizens' group, Picard, 2019, in which state services, elected officials, and scientists were taken to task on this subject; more details are presented in Devès et al., 2022a, b; Fallou et al., 2020; and Mori, 2021, 2022); (ii) despite a large quantity of public information documents issued by scientists and the authorities (Devès et al., 2022a), the significant feeling of a “lack of information” within the exposed population documented by Fallou et al. (2020) raises questions about the transmission chain of this information to the public; (iii) risks are perceived mostly indirectly by at-risk populations, which poses specific challenges for public information (Skotnes et al., 2021); (iv) there are large uncertainties, some of them still ongoing as we write; and, finally, (v) the activity is long-lasting, allowing us to study the evolution of a large amount of coverage over time.

3.1 Selection of articles

The same selection of articles as in Devès et al. (2022b) and Devès et al. (2023) is used. This selection contains articles from six French-language daily newspapers published between 10 May 2018 and 10 May 2021. The methodology for creating this selection is inspired by Le Texier et al. (2016) and Devès et al. (2019). Newspapers were selected based on four criteria: (1) the number of articles published regarding this case study, (2) the breadth of readership, (3) the spatial distribution of the readership along with the structural and cultural links existing between the region and the study area, and (4) a specific language (French in this study). Six French-language daily newspapers were selected among 56 sources mentioning these events, addressing national (Le Monde, Le Figaro), regional (L'Express de Madagascar, Journal de l'île de La Réunion), and local readerships (Journal de Mayotte and Mayotte la 1ère); see Fig. 2 and Sect. S1 in the Supplement. Articles were then collected from two types of sources: (1) Factiva and Europresse, two full-text press databases offering a selection of general, specialised, paywalled, or freely accessible newspapers with regional, national, and international readerships, and (2) web archives, especially for local press articles which cannot be found in those two databases. The Factiva and Europresse databases are often used by scholars to study media coverage (Severo et al., 2015; Reboul-Touré, 2021; Bernier et al., 2013).

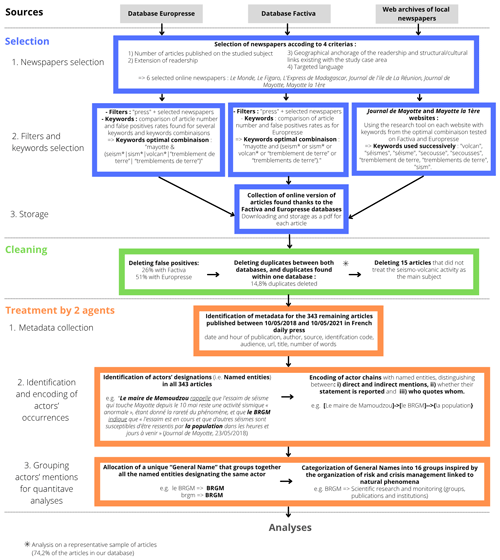

Figure 2Schematic workflow for article collection and processing. The articles are selected from three main sources using a combination of keywords (see Supplement for more details on the keyword analysis). Articles are all initially read to identify and remove false positives and duplicates. False positive and negative rates are determined on representative samples (see Supplement). Each article is then read independently by two to three researchers who complete a data table with metadata and coded variables. Disagreements were discussed and resolved collectively.

The resulting database is composed of 358 articles published between 10 May 2018 and 10 May 2021, thus covering the first 3 years of Mayotte's seismic-volcanic crisis. This selection of articles was limited to May 2021, after which pictures taken underwater and graphical representations of the phenomenon began to be regularly broadcast by these media. This date also corresponds to when articles in the local press became less frequent. Within this database, 15 articles were excluded from this study to ensure the selection contained only news items whose main subject was the seismo-volcanic activity. Therefore, the final database includes 343 articles and covers the first 3 years of the recent seismo-volcanic unrest near the archipelago of Mayotte.

3.2 Indicators

3.2.1 Actors and categories of actors

The term “actor” is used with a broad definition which encompasses both individual and legal entities, groups of individuals sharing a common character or purpose – such as a scientific mission or being impacted in the same way by the crisis – but also media agencies that play an active role in communicating about the event (Agence France Presse, X formerly known as Twitter, scientific journals, etc.). Places or buildings (mobile like a boat or immobile like a school) may be described in the media as actors when they are named as a proxy for the individuals they host and were therefore also included. Devès et al. (2022a) provide a detailed account of actors and actor categories and outline their expected roles, responsibilities, and capacities during the crisis.

To study the press coverage of different categories of actors, a double-reading process was employed. Two researchers independently reviewed the articles to identify each actor or group of actors mentioned, even when they were identified by professional status, by nicknames, etc. This qualitative analysis of the texts disambiguated the majority of references to actors in the texts. For example, the terminology “experts” can be used to refer to scientists specialising in the hazard and to technicians from the Bureau Veritas in charge of assessing the damage, and some actors have different affiliations depending on articles due to errors or evolutions in their career (e.g. Nathalie Feuillet, a researcher, was wrongly affiliated with IFREMER in some articles, such as in an article published in the Journal de Mayotte on 7 May 2019). A careful reading of the articles was thus necessary and generally enabled the actors to be categorised (see Table 1). The remaining actors are labelled as “unidentified” in the diverse/unidentified category (see Sect. S2 in the Supplement). When an actor is identified in an article, their exact denomination(s) is noted (i.e. named entities), and we build two correspondence tables that allow us to (i) identify the different ways of naming the same actor and group them under a chosen “general name” (TABLE NamedEntitiesToGeneralName in TABLE SA) and (ii) group these actors into categories (see TABLE GeneralNamesToCategories in TABLE SB for a correspondence table between “general names” and “categories”) in order to build a structural analysis.

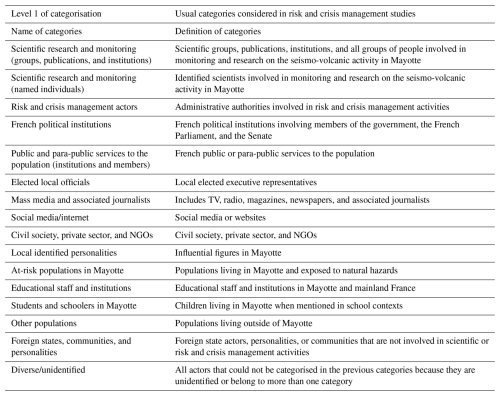

Table 1Denominations and definitions of categories used to group actors identified by two researchers in a database of 343 daily press articles published between 10 May 2018 and 10 May 2021 covering the first 3 years of the recent seismo-volcanic unrest in the Mayotte archipelago. Categories are determined according to the organisation of risk and crisis management in France (see Fearnley and Beaven, 2018, and Sect. S2.2 in the Supplement).

3.2.2 Direct and indirect mentions, reported speech, and simple mention

A direct mention occurs when an actor is cited in the text by the author of the article without being introduced by another actor. An indirect mention occurs when an actor is mentioned through a third party in the article. For example, in the sentence, “The prefecture reports that an earthquake with a magnitude of 4.0 was recorded by the Bureau of Geological and Mining Research (BRGM)”, the mention of the prefecture, which is the body representing and implementing government policy at the local level, is considered direct, while the mention of the BRGM is considered indirect. This distinction allows us to analyse the interactions between actor categories in the press. Specifically, it helps identify the most frequent citation links, the direction of these relationships (and therefore their potential asymmetry), and, finally, the central position of actors and actor categories within the citation network.

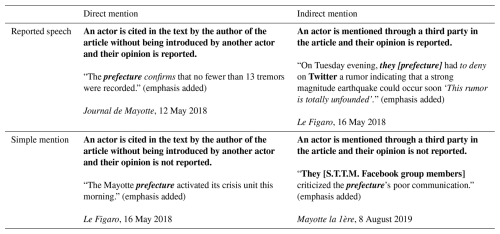

Reported speech and simple mentions of actors are also distinguished (see Table 2). Reported speech can be direct or indirect. Reported speech is defined as any text that the journalist presents as the words or opinions of an actor, whether it appears to be reported directly (e.g. with the use of quotation marks), indirectly, or even in a distorted manner. For example, in the sentence, “In May 2018, when the swarm of earthquakes began to shake Mayotte, the first scientists rushing to the island did not believe in volcanic activity”, the phrase “did not believe in volcanic activity” is considered to be reported speech since the news item is intended to convey their beliefs. In contrast, in the sentence, “End of mission: French prefect Dominique Sorain leaves Mayotte”, Dominique Sorain is “simply mentioned”.

Table 2Examples illustrating the distinctions between direct and indirect mentions and between reported speech and simple mentions, using the actor “prefecture”, which is the body representing and implementing government policy at the local level, as an example. Bold format refer to the actor in question, or to the one introducing this actor in the text. Italic format indicates either direct citations from an actor or words specifying whether the actor’s speech is being reported. The actor currently being discussed is shown in bold italics.

3.2.3 Actor network analysis

The system of actors depicted by the network of citations is studied to better understand the relationships between individual actors, actor categories, and their evolutions. This is accomplished using node-level centrality indices, including in-degree, out-degree, and betweenness centrality, computed with the igraph package in R. Network diagrams plot citation links with arrows, and the size of the nodes and font size of generic names are weighted according to their degree, representing the number of direct connections each node has within the citation network. Unidentified actors are removed from the graphs to avoid generating false co-citation relationship structures.

To study the position of the actors in the citation networks (source and destination of a citation) derived from the selection of articles, two node-level indicators from network analysis are used: degree centrality and betweenness centrality. Degree centrality measures the number of links held by a node. It captures the extent of an actor's connections in the media through the citation process. There is a distinction between in-degree (the number of times an actor is mentioned by others) and out-degree centrality. Actors with the highest out-degree values are those most active in transmitting the experiences, opinions, speeches, and actions of other stakeholders (including Mayotte's population). Conversely, a high in-degree index indicates a central position in the network resulting from strong interest from third parties. The ratio between in-degree and out-degree centrality reveals the level of reciprocity in these interactions.

Betweenness centrality measures the number of times a node lies on the shortest path between two other nodes. The values are normalised by the number of node pairs in the graph (the direction of citations is not accounted for). A high betweenness index indicates that an actor plays an important bridging role, connecting different parts of the network. This is particularly true for the subgroups revealed by the citation patterns, either because they position themselves at the centre of the network or because they are positioned on the periphery of several clusters.

Here, eight graphs, corresponding to the eight major periods of seismo-volcanic activity press coverage proposed by Devès et al. (2022b), are presented. This allows us to examine the evolution of the network at different periods, each characterised by the occurrence of a new triggering event (e.g. the first earthquakes, first discussions regarding the hypothesis of a volcanic origin, the discovery of the volcano, or a public conference).

4.1 Actors' mentions in the selection of articles

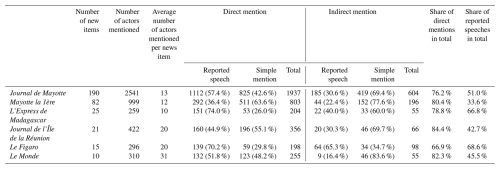

Table 3 presents a set of descriptive statistics on the frequency and form of actor mentions in this selection of articles. The publication frequency varies among the newspapers studied: the national daily Le Monde devoted 10 articles to the subject, while 190 articles were published by the local daily Journal de Mayotte. These varying publication rates result in different actor mention rates: Le Monde names 310 actors (often repeatedly), while this number peaks at 2541 for the Journal de Mayotte. Beyond this rate effect, differences also emerge in the diversity of the actors mentioned: Le Monde, the national daily Le Figaro, and the regional daily Journal de l'Île de la Réunion mentioned an average of 31, 20, and 20 actors per news item respectively, while this mean value was only 13 for the Journal de Mayotte and 12 for the local daily Mayotte la 1ère, dropping to 10 for the regional daily L'Express de Madagascar. An inverse relationship emerges between publication rates and the average number of actor mentions per article. Ultimately, the position of actors in the citation network is largely driven by the most prolific media. This effect is controlled for in this analysis through the use of relative indicators.

Table 3Proportions of reported speech and simple mentions across the six selected newspapers. This table presents data from 343 press articles, published between 10 May 2018 and 10 May 2021, on the seismo-volcanic activity off the coast of Mayotte. An indirect mention refers to when an actor is introduced in the press discourse by a third party, as opposed to a direct mention. A distinction is drawn between actors whose speech or opinion is reported (anything presented as their word or opinion, even if distorted) and actors that are simply mentioned.

Another source of variability in actor coverage lies in the balance each newspaper strikes between direct and indirect mentions and between reported speech and simple mentions. While for most newspapers, direct mentions constitute approximately 80 % of the total (compared to 20 % for indirect mentions), this proportion drops to 66.7 % for the national daily Le Figaro. However, this newspaper also distinguishes itself by the highest frequency of reported speech (68.6 %), both for direct mentions (70.2 %) and for indirect ones (65.3 %). The regional daily L'Express de Madagascar also features a high proportion of reported speech (66.8 %), but this is driven primarily by actors mentioned directly (74 %) and applies to a much lesser extent to those mentioned indirectly (40 %). The local daily Mayotte la 1ère has the lowest rate of reported speech (at 33.6 %), followed by the regional daily Journal de l'Île de la Réunion (42.7 %) and the national daily Le Monde (45.5 %). Consistently, the proportion of reported speech is invariably lower for indirectly mentioned actors than for those mentioned directly.

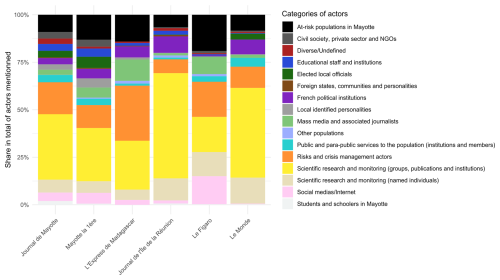

Beyond these structural characteristics, the newspapers distinguish themselves by the prominence given to different actor categories (Fig. 3), revealing distinct narrative specialisations. Although actors related to scientific research and monitoring (groups, publications, and institutions) are the most prominent category in all the newspapers, their proportion varies significantly from one outlet to another: they are particularly prevalent in the regional daily Journal de l'Île de la Réunion and, to a lesser extent, in Le Monde, while they represent less than a quarter of the actors mentioned by the national daily Le Figaro. This trend is reinforced when specifically named scientific and monitoring actors are also considered.

Figure 3Relative share of crisis actor categories across different media outlets. The actor categories were developed based on the organisational structure of risk and crisis management in France (see Fearnley et al., 2018, and Sect. 2).

The second-most prominent category of actors is risk and crisis management actors. Here, too, this proportion varies from one outlet to another, with the highest rates observed in the regional daily L'Express de Madagascar and in the national daily Le Figaro. Interestingly, at-risk populations in Mayotte do not exceed a quarter of the total share of actors mentioned in the media. In some newspapers, such as the local daily Journal de Mayotte, the regional daily Journal de l'Île de la Réunion, or Le Monde, they do not exceed 1/10. The relative presence of other actors is more variable from one outlet to another; for example, citations of social networks are more common in Le Figaro than in other newspapers, and a lower frequency of actors from French political institutions is observed in local newspapers than in national and regional newspapers (with the clear exception of Le Figaro).

4.2 Direct and indirect speech by actor category

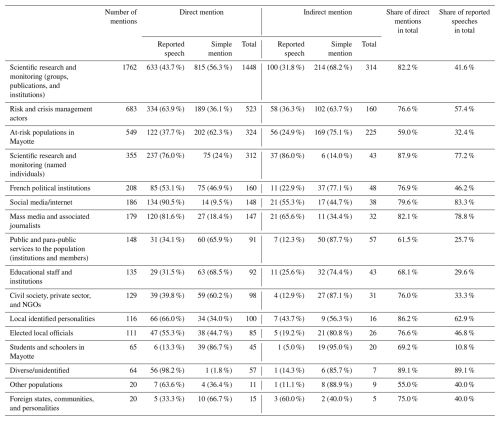

Table 4 reports the number and share of direct and indirect mentions and reported speech and simple mentions by actor category in the entire selection of articles. While most actor categories are primarily mentioned directly (i.e. without an intermediary), for certain groups, indirect mentions are more common. This is particularly true for at-risk populations in Mayotte, which, in more than 40 % of cases, are mentioned indirectly. The share of direct mentions is also relatively low for public and para-public services and for students and schoolers in Mayotte (over 30 % indirect mentions). Conversely, specifically named scientific and monitoring actors and identified local personalities are the groups most frequently mentioned directly.

Table 4Key statistics on actor category mentions across all articles. Data were compiled from 343 press articles, published between 10 May 2018 and 10 May 2021, on the seismo-volcanic activity off the coast of Mayotte. An indirect mention refers to when an actor is introduced in the press discourse by a third party, as opposed to a direct mention. A distinction is drawn between actors whose speech or opinion is reported (anything presented as their word or opinion, even if distorted) and actors that are simply mentioned.

Significant variations exist between actor categories regarding the proportion of reported speech compared to simple mentions. The analysis shows that scientific, media, and institutional actors are granted more frequent reported speech than actors from civil society. For instance, the proportion of reported speech for students and schoolers in Mayotte is only 10.8 % and 32.4 % for at-risk populations in Mayotte. In stark contrast, it reaches 62.9 % for local personalities, 77.2 % for specifically named individuals in science and monitoring, 78.8 % for mass media and associated journalists, and 83.3 % for social media/internet sources. Among the categories identified, only specifically named scientific actors and foreign states, communities, and personalities have a higher share of reported speech when mentioned indirectly than when mentioned directly.

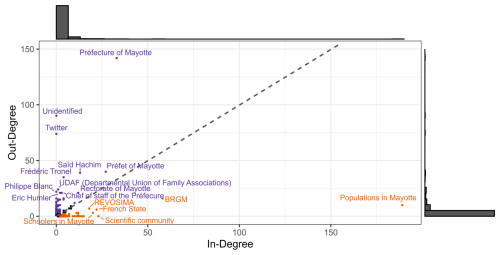

4.3 Position of actors in the citation network

A cross-analysis of the frequency with which actors are identified as a source or recipient of a quotation in the selection of articles (Fig. 4) indicates that the prefecture of Mayotte and its main representatives play a central role in communicating about the event, as their media appearances largely lead to the mention of other actors. Many mentions of actors also originate from the X (formerly Twitter) network, which appears to be an essential primary source in the media narrative. A few local personalities also emerge as central nodes in the network, relaying information concerning a large number of actors. These include (i) Saïd Hachim, a geographer from Mayotte (Mahoran) who works at the Departmental Council of Mayotte and is also a PhD candidate in geography at Paul Valéry Montpellier 3 University in mainland France; (ii) Lieutenant Colonel Philippe Blanc, a member of the Directorate-General for Civil Protection and Crisis Management who operates at a national level and was sent to Mayotte in June 2018 as a member of an interministerial delegation for civil protection; (iii) Eric Humler, scientific director of REVOSIMA from 2019 to 2022 and in charge of the coordination of the Tellus Mayotte mission; and (iv) Frédéric Tronel, the regional director of the French geological survey (BRGM) in Mayotte from 2017 to 2020. The Union des Affaires Familiales (UDAF) emerges as a key player in the actor citation chains within the selection of articles. In contrast, the Mahoran population and, to a lesser extent, schoolchildren, are highly cited but rarely initiate citations of other actors, indicating a relatively passive position within the citation network extracted from the selection of articles. This is also the case for the French geological survey (BRGM), REVOSIMA, and the scientific community (in general), which are regularly used as a source of information by third-party actors whose words are reported (directly or indirectly) in the articles.

Figure 4In-degree and out-degree distributions by actor category across all articles. This scatterplot shows the number of times an actor initiates a citation chain (out degree) versus the number of times they are mentioned as a recipient of a citation (in degree). Actors who are most often the source of the citation (and who are more often a source than a recipient) are annotated with purple labels. Conversely, actors who are most often the subject of the citation (and who are more often a recipient than a source) are annotated with orange labels.

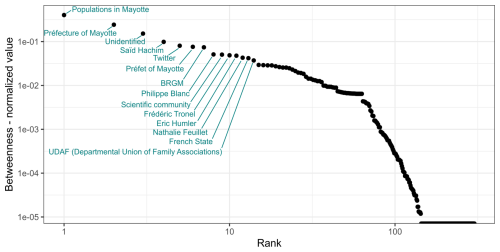

Figure 5 shows an exponential relationship between the normalised values of the betweenness indices and the ranks, indicating a hierarchical structure of the network through the concentration of citation interactions by a small proportion of actors. The Mahoran population emerges as a key connecting element of the network of actors constructed from citation links in the media, a role also prominently filled by the local expert Saïd Hachim. The central role of the prefect and the prefecture, representing the French State in the department, is also evident. The scientific community as a whole, the French geological survey (BRGM), and REVOSIMA also appear to be essential elements in structuring the network, as is the social media platform X (formerly Twitter), which allows media visibility for individuals and institutions and promotes citation chains via re-tweets and mentions. Individuals with many connections also have high degrees of betweenness: Philippe Blanc, Eric Humler, and Frédéric Tronel (mentioned above), as well as Nathalie Feuillet, an observatory physicist at the Institut de Physique du Globe de Paris (IPGP) and mission leader of the first oceanographic campaigns (MayObs 1 and 2; see Feuillet, 2019, and Jorry, 2019), who, despite having lower in-degree and out-degree values, connects a relatively large number of the shortest paths in the network.

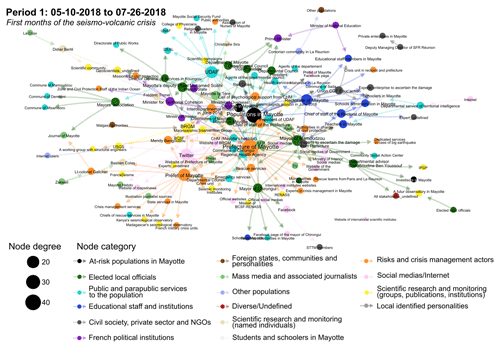

4.4 Actor network structure

The 126 articles published during the first months of the crisis (Period 1, from 10 May 2018 to 26 July 2018) reflect a network of highly interconnected actors structured around key figures attracting a certain number of citations (Fig. 6). These include the Mayotte population as a whole, the prefecture of Mayotte and the prefect, the Union des Affaires Familiales, and actors of the educational system (including the rectorate, the decentralised government department for education, and teachers) but also mayors (the association of mayors, the mayor of Mamoudzou (the capital city), the mayor of Chirongui, and other municipalities) and the social network X (formerly Twitter).

Figure 6Actor citation network from press coverage during the first months of the seismo-volcanic crisis.

The citation network is extensive, and all categories of actors are present with the exception of local personalities (although many groups made up of members from civil society, associations, and businesses appear in the network). Interestingly, while the citation chains from the entire selection of articles show paths between actors belonging to the same category, the network itself presents a certain heterogeneity. The prefecture of Mayotte relayed information not only from local and other national risk and crisis management actors, but also from scientific research and monitoring institutions, groups, and publications, and was cited by and communicated through a variety of mass media and social media. The articles in this selection also make it possible to link the prefecture of Mayotte to the Mahoran population, as well as to various public and para-public services such as hospitals. Thus, the prefecture emerges as the central actor in the management of this first period of the seismo-volcanic activity, which is in accordance with its official mandate for public safety and state representation. Notably, the prefect's interventions and mentions in the press do not link him to the same actors as the institution he represents. His communications were aimed at the civilian population and representatives of civil society and associations, stakeholders in the educational world, and mayors. Actors from the delegation of specialists in civil security and natural risks, such as Mendy Bengoubou, appear as intermediate nodes between the prefecture and the prefect, with whom they share a large number of co-cited actors. Conversely, in these first months of the crisis, the citation networks between scientific actors appear fragmented, and local elected officials seem relatively peripheral.

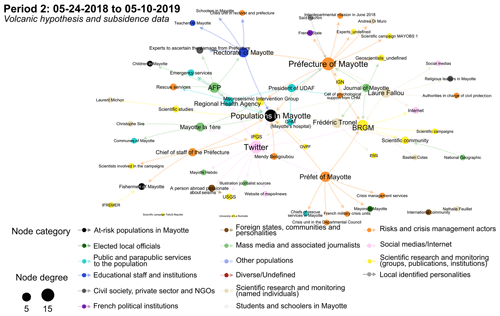

The citation network for the second period, derived from 29 articles published between 5 October 2018 and February 2019, is shown in Fig. 7. These articles focused on the emergence of the volcanic hypothesis and the first subsidence data. As in the first period of the crisis, the population (cited by numerous actors but never initiating a citation) is at the centre of the network. The prefecture and the prefect (and to a lesser extent, the prefect's chief of staff) still emerge as central nodes, initiating numerous citations. Only the prefecture, as an institution, receives a significant number of citations in return (19 citations, 10 for the prefect) from various actor categories. Once again, the institution is separated from its two key figures (prefect and chief of staff) within the citation network, with the exception of common citations of the population and the BRGM. The BRGM is also the destination of numerous citations (24) from scientific actors, which allows it to partially aggregate them within the network. Two scientific personalities stand out for the number and diversity of co-citation links they create: Laure Fallou and Frédéric Tronel. The first is a sociologist at the Euro-Mediterranean Seismological Centre (EMSC) who wrote an academic paper highlighting the emergence of a mistrustful atmosphere and the circulation of misinformation due to a lack of scientific information linked to the scarcity of seismic data. Although Fallou et al. (2020) was published in 2020, it was also the subject of public communication at the General Assembly of the European Geosciences Union in April 2019. The second was the regional director of BRGM in Mayotte between 2017 and 2020.

Figure 7Actor citation network following the emergence of the volcanic hypothesis and first subsidence data.

In contrast, Nathalie Feuillet (an observatory physicist), the University of La Rochelle in mainland France, and the Tellus Mayotte oceanographic mission from IPGP are isolated. Christophe Sira, a macroseismic surveyor and member of the Groupe d'Intervention Macrosismique, and Laurent Michon, a research professor at the University of La Réunion, are also separated from other scientific actors. Likewise, Bastien Colas and Mendy Bengoubou, two of the three members of the delegation of specialists in civil security and natural risks dispatched by two ministries (Ministry of Ecology and Ministry of the Interior) to assess the seismo-volcanic activity on site in June 2018, are cited separately from each other and from the interdepartmental mission itself, while the third expert, Lieutenant Colonel Olivier Galichet, is not mentioned in the selected articles. Once again, actors in the medico-social world, who initiate citations of various actors, have intermediate positions in the network, while actors in the educational world are more isolated than during the previous period. Another important distinction is the introduction of a first identified local personality, Saïd Hachim, in the network. In this subset of articles, he only cites the prefecture, as he relayed and detailed a note from the institution mentioning the volcanic origin hypothesis derived from the latest GPS data. Local fishers also appear in the network of actors via citations from IFREMER and the prefect's chief of staff, following the discovery of deep-sea dead fish about 50 km east of the coast.

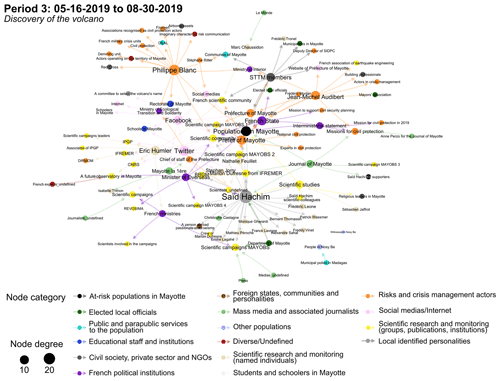

The third period studied corresponds to the discovery of the underwater volcano and covers 36 articles published from 16 May 2019 to 30 August 2019. Figure 8 depicts its actor co-citation network. Compared to the previous periods, the central connecting role of the population is diminishing, while the position of local actors acting either as relays for residents' voices (such as the Facebook group Signalement Tremblement de Terre Mayotte, or S.T.T.M.) or as relays for scientific voices (such as Saïd Hachim) is strengthened. Philippe Blanc, as a member of a civil security mission on volcano-related risks, also appears as an important source of citations in the network, mainly for other risk and crisis management actors, without receiving any citations in return. The same is true for Jean-Michel Audibert, who was part of the same mission for civil security; the two actors are only connected by their shared citation of the Mahoran population.

The various ministries involved in crisis management and the French State are only indirectly connected to each other, reflecting segmented cooperation networks, even within the framework of inter-ministerial actions. The Ministry of Overseas Territories introduces numerous actors into the citation network, including REVOSIMA (Mayotte's volcanological and seismological monitoring network), which was created on 18 June 2019, and a hypothetical future observatory in Mayotte, which is still in the planning stage at the time of writing. The network of scientific actors is more structured and includes more numerous, diverse, and international actors than in the previous periods. Indeed, the recording of the waves of a very-long-period earthquake all over the world on 11 November 2018 has attracted the attention of international institutions and media in addition to that of scientific and political authorities at the national level (Hossein and Sadaomi, 2021). Notably, the scientific actors named by Eric Humler or via the X (formerly Twitter) network differ from those named by Saïd Hachim, who mainly relays the names of scientists with whom he had published an atlas of natural risks and vulnerabilities of Mayotte in 2014 and discusses the MayObs campaigns. Several social networks, the Facebook group S.T.T.M., and two local newspapers appear as important nodes of the citation network, mainly citing other media, the Mahoran population, scientists (with the exception of the S.T.T.M. Facebook group), public institutions, and the actors of the MayObs oceanographic campaigns carried out from the Ifremer ship Marion Dufresne. Interestingly, the members of the MayObs oceanographic campaigns are not cited by the same actors, reflecting a sequencing of the actors mentioned in the media as the oceanographic campaigns progress (the prefecture, the prefect, and X (formerly Twitter) for the first campaign and the Ministry of Overseas Territories and Saïd Hachim for the fourth, while interministerial communiqués do not distinguish between the different missions).

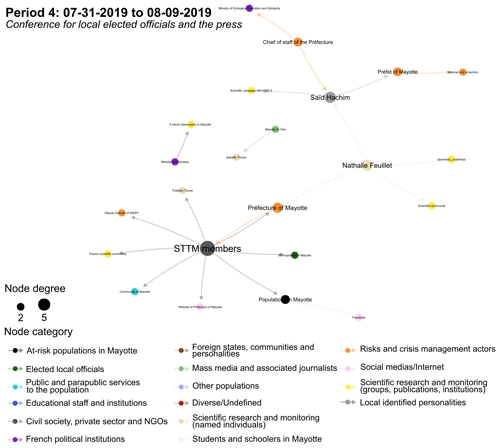

Period 4 focuses on a specific event within Period 3: a conference for local elected officials and the press, organised by the prefecture and led by scientists involved in the volcano's discovery. This period covers six articles published between 31 July 2019 and 9 August 2019.

As shown in Fig. 9, Nathalie Feuillet acts as an intermediary, connecting the part of the network structured around Saïd Hachim with the S.T.T.M. Facebook group. She creates this link via her citation of the prefecture which quotes and is quoted by the S.T.T.M Facebook group. Without this connection, the actor network appears fragmented, even among key actors: scientists, state representatives (the prefecture, the prefect, and his chief of staff), the Interministerial Defense and Civil Protection Service (SIDPC), the Ministry of Overseas Territories, and the Ministry of Ecological and Inclusive Transition. Frédéric Tronel and Isabelle Thinon are the only scientists cited by other actors: Tronel is cited by the S.T.T.M. Facebook group, while Thinon is cited by the local news broadcast Mayotte la 1ère. This low presence of named scientific actors is compounded by the absence of specific scientific institutions, which are instead referred to abstractly as “the scientific community”.

Figure 9Actor citation network from press coverage of the conference for local elected officials and the press.

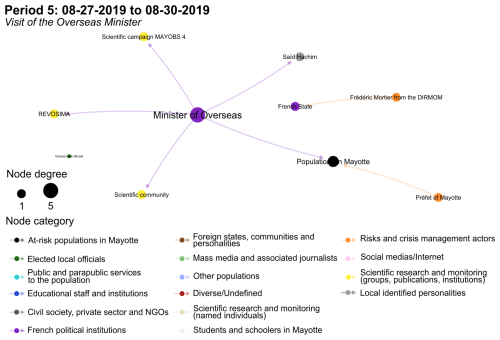

Period 5 (Fig. 10) focuses on a second specific event within Period 3: the visit of the minister for Overseas France to Mayotte. This period covers three articles published between 27 August 2019 and 30 August 2019. As depicted in Fig. 10, the number of cited actors is low. The minister for Overseas France occupies a central place in the network, as they mention five other actors: the scientific actors responsible for studying the phenomenon (REVOSIMA and the underwater observation campaign MayObs 4), the scientific community more generally, the local expert Saïd Hachim, and the Mahoran population (also cited by the prefect). The isolated mention of the French State by Frédéric Mortier (from the interministerial delegation for major overseas risks, DIRMOM) and a separate mention of local elected officials can also be noted.

Figure 10Actor citation network from press coverage of the minister for Overseas France's visit to Mayotte.

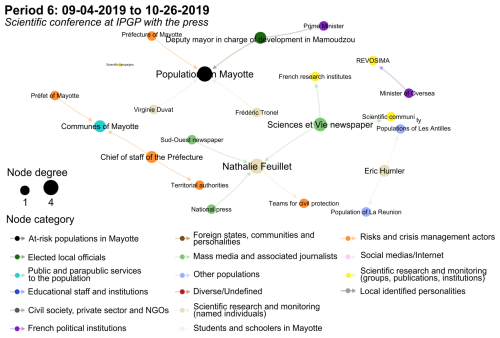

Eight articles in the selection of articles cover the period from 4 September 2019 to 26 October 2019 (Period 6, Fig. 11). This period encompasses a scientific conference held at the IPGP headquarters in Paris, immediately followed by a public conference hosted by scientists and ministerial officials.

Interestingly, REVOSIMA (once again solely cited by the Ministry of Overseas Territories) is isolated from the rest of the citation network (Fig. 11), even though it brings together the actors in charge of the volcanological and seismological monitoring of Mayotte. It is, nevertheless, the only scientific institute explicitly named, as the citation network gives a more central place to individual scientists than to institutions. The actor network is more fragmented than in previous periods, and its sub-networks are organised around Nathalie Feuillet (who received citations from various media), Eric Humler (quoting populations from other French overseas departments), the chief of staff of the prefecture (citing the communes of Mayotte and territorial authorities in general), and the journal Sciences et Vie (citing Nathalie Feuillet and encompassing the scientific community and French research institutes). Several isolated citations again point to the Mahoran population (from scientists Virginie Duvat and Frédéric Tronel but also from the prefecture of Mayotte and a local elected official from the capital city, Mamoudzou). Once again, the prefecture of Mayotte is separated from the prefect and his chief of staff within the citation network. For the first time, the prime minister is cited by an actor – specifically, the deputy in charge of development in Mamoudzou – regarding a letter sent to the prime minister to point out the effects of subsidence on urban development.

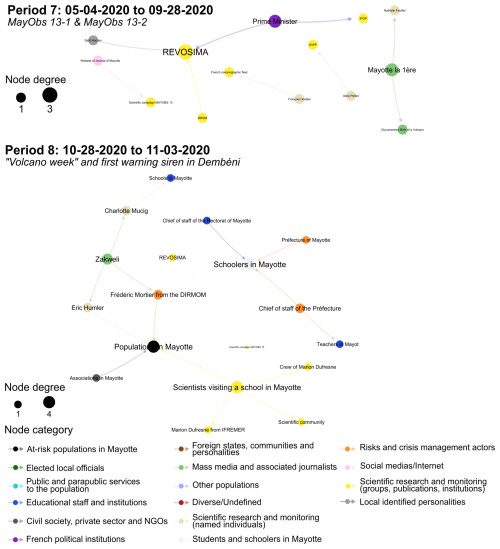

Period 7, which extends from 4 May 2020 to 28 September 2020 and covers the missions MayObs 13-1 and MayObs 13-2, is covered by seven articles from the selection of articles. Its citation network is shown in Fig. 12. For the first time, REVOSIMA appears as a central node of the network, although the number of nodes and links is limited by the small number of articles. REVOSIMA is cited by local expert Saïd Hachim and by the prime minister but also by BRGM, one of its member institutions. The prime minister also cites IPGP separately from REVOSIMA, even though IPGP is one of the institutions responsible for it. The network of scientific actors appears generally fragmented during these two missions. Notably, the documentary Birth of a Volcano, produced by Crestar Productions and L'éolienne and broadcast on Mayotte la 1ère, is not relayed by any actor other than the channel.

The last period extends from 28 October 2020 to 3 November 2020 and covers two events recounted in six articles: the “volcano week” and the first siren alerts in the municipality of Dembéni. The actor network (Fig. 12) is structured around two main components. The first is organised around Mahoran schoolchildren and includes citations from the chief of staff of the Mayotte rectorate, the chief of staff of the prefecture, and the prefecture itself. Teachers in Mayotte are also part of this citation chain, as they are cited by the chief of staff of the prefecture. Interestingly, schools in Mayotte (mentioned as actors) belong to the second citation sub-network, of which they form the periphery through a citation by Charlotte Mucig, who was in turn cited by the TV and radio show Zakweli, broadcast by Mayotte la 1ère. The show Zakweli also links Eric Humler and Frédéric Mortier, both of whom cite the Mahoran population. The latter is also cited by unidentified Mahoran associations, as well as by scientists visiting Mahoran schools during the volcano week, who also mention the MayObs missions on the ship Marion Dufresne either explicitly or implicitly. Finally, REVOSIMA appears fully isolated from the other actors.

Figure 12Actor citation networks during two key periods. In Period 7, the focus is on the organisation and execution of two campaigns at sea, MayObs 13-1 and MayObs 13-2. In Period 8, attention shifted to two communication initiatives from the Mayotte prefecture: the “volcano week” (a series of conferences and activities for schoolers) and the installation of the first public warning siren on the territory.

Mass media play a key role in risk and crisis communication, serving as the main information source for millions of people regarding natural, political, and social events (e.g. Gamson and Modigliani, 1989; Allan et al., 2000; Dixon, 2008; Aday, 2010). They influence people's perceptions of various actors involved in understanding and monitoring hazards and managing their effects, as well as their performance during events (Harris et al., 2012). Despite the focus on newspaper representations rather than those among populations and the use of articles from six non-specialist French-language newspapers, this study provides comprehensive insights into media narratives during the seismic-volcanic crisis in Mayotte from May 2018 to May 2021. The inclusion of additional local, regional, and national daily papers in different languages and other media forms could deepen the analysis. However, the chosen selection of articles, primarily from the non-specialist daily press, remains a strong candidate for studying representations conveyed by the media as a whole (Cagé et al., 2017). This is especially true given that this selection includes Mayotte la 1ère, an outlet that operates across multiple platforms (TV, radio, and a website) and produces content in both French and Shimaore, ensuring a wide local audience and considering the dynamics and complementarity between quantitative and qualitative analyses facilitated by written press data.

When examining the results, it is crucial to acknowledge the influence of journalistic practices. Newspapers, acting as mediators in the broadest sense, have their own practices and priorities in collecting and disseminating information. Daily newspaper journalists, who are often generalists with diverse profiles and working methods (Ruellan, 1992), are commonly bound by the constraint of tight deadlines. This limitation may affect their ability to access multiple sources or to investigate the context in depth. Consequently, they tend to prioritise information that is deemed reliable, easily accessible, and of interest to their readership (van Belle, 2015). Geographic proximity to events influences coverage (e.g. Cavaca et al., 2016), with local journalists having easier access to the field and local actors. This is evident in the composition of the selected articles, with a predominant 78 % (and 54 % in the Journal de Mayotte alone) being published in local newspapers. These local articles typically take the form of concise press releases offering updates on the latest developments. In contrast, national newspapers, faced with the challenge of engaging a readership approximately 8700 km away and not directly impacted by events, tend to favour less frequent but more extensive publications providing summaries or in-depth analyses (see Sect. 4.1: an average of 20–31 actors are mentioned per article in national newspapers, compared to around 10 in local newspapers). This also influences the selection of quoted sources, with local journalists relying more on local actors and national journalists adopting alternative strategies, such as using social networks (e.g. X and Facebook for national dailies like Le Figaro and Le Monde) or relying on news agencies like Agence France-Presse (AFP) or their local counterparts (Lecheler and Kruikemeier, 2016), directly or indirectly, via associated press (e.g. Reuters) who provide articles for international media based on local reporting. This is illustrated here by Le Figaro and Le Monde, which present a comprehensive view of the involved actors, albeit with less ease in reporting their statements. Given their time constraints, journalists typically favour sources they consider legitimate and relatively easy to access. For instance, the municipality of Chirongui stands out, as the mayor at the time remained in office from 2008 to 2020, and her team appears to have been particularly active and well integrated into the local community. Moreover, it hosted the delegation of specialists in civil security and natural risks dispatched by two ministries (Ministry of Ecology and Ministry of the Interior) (Journal de Mayotte, 6 June 2018), and this event served as an entry point for the presentation of the group in the local press. Another example is the Union des Affaires Familiales (UDAF), which emerges as a key player in the actor citation chains within the selection of articles. This can be explained by the meeting they organised on 5 June 2018 to relay people's experiences and promote dialogue between local actors (among them, state institutions, public and para-public services, local elected representatives, etc.) regarding measures to be taken at the start of the seismic crisis (Le Monde, 14 June 2018; Journal de Mayotte, 1 June 2018), which was relayed by both local and national press. The choice of sources may vary based on editorial stance (Shoemaker and Reese, 1996; Kaiser and Kleinen-von Königslöw, 2019). For example, in this context, local newspapers, which are seemingly inclined to emphasise the local context in comparison to national and regional newspapers, exhibit a lower rate of reported speech from French political institutions. As observed in these findings and reinforced by Ploughman (1997), journalists tend to have more accessible and regular contact with certain types of sources, including public institutions, officials, or high-profile personalities, who are consequently more prominent in the news.

Having acknowledged the influence of journalistic practices, this study shows that using this method to scrutinise press coverage also allows for the identification of actor groups typically present in a crisis context related to a natural phenomenon (e.g. Fearnley et al., 2018; Trias et al., 2019; González, 2022). First of all, the main trio in crisis management emerges as the most mentioned and quoted actors in this network: scientists overseeing monitoring, authorities responsible for civil protection, and at-risk populations (Fearnley et al., 2018; Devès et al., 2023). Other categories, such as mass media, social networks, civil society, public and para-public services, and even humanitarian aid associations (e.g. the Red Cross), are also well represented. However, the latter are less prevalent than in other crises, likely due to the limited physical impacts (e.g. minor building damage and few injuries). Notably, international actors, including personalities, newspapers, communities, and states, are also present, which suggests the importance of these external points of view as reported by other actors within the crisis narrative. This is also highlighted in previous studies as indicative of a growing interconnection between actors in the disaster risk reduction context on an international scale (e.g. Trias et al., 2019). In the case of this very local, small-scale crisis, the mere presence of international reactions becomes an event worth reporting by others. The actors involved in crisis management, organised by the Organisation de la Réponse de Sécurité Civile (ORSEC) in France, are also represented. Under the ORSEC framework, mayors coordinate emergency services and public facility management (hospitals, schools, etc.) if the event is local. If damage extends department-wide and surpasses the capacity of town halls, the prefecture assumes control. Ultimately, the crisis is managed by the regional headquarters (EMZCOI for Mayotte), then by the French government if the lower levels are overwhelmed. However, here, despite the limited physical impact of this crisis, it was mainly the prefecture and national civil protection services (under the responsibility of ministries) that were mentioned and whose speech was reported. Local elected representatives, including mayors, are surprisingly less present than other actors who theoretically play a lesser role (such as civil society, local personalities, and public and semi-public services, including education staff), while the regional headquarters is rarely mentioned. These asymmetries in representation partly reflect Mayotte's unique situation as a French overseas department, with part of its administration, including the regional headquarters, based more than 1400 km away in Réunion. This region, while distant from the mainland, poses specific challenges requiring a substantial response from the national authorities responsible for crisis management (Cottereau, 2021; Roinsard, 2022; Duchesne, 2023). Another specific feature also observed in several overseas departments is a lesser degree of cooperation between local elected representatives and national representatives located in these departments (Lemercier et al., 2014; Gillet et al., 2023). Overall, we obtain an overview of the diverse actors involved in this crisis management and communication, aligning with findings from other studies using similar (e.g. Rajput et al., 2020) and different methodologies (e.g. Villodre and Criado, 2020; Calabro et al., 2020).

Additionally, the results underscore the emergence of various actors or groups of actors within the population, a facet that is not treated homogeneously in official or legal texts. In particular, several local figures can be identified, as has been noted in other case studies (e.g. Devès et al., 2019). The temporal evolution of the network yields several insights. The notably dense network observed during the first 2 weeks of the seismic crisis reflects both the unprecedented nature of the hazard and the initial difficulty faced by the media, and by many of the actors interviewed, in identifying reliable or authoritative sources. This is unsurprising, as the hazard had no precedent in living memory on the island (Cripps and Souffrin, 2020), and the only scientific institution present at the onset of the crisis was the BRGM. This highly disorganised yet progressively clarifying and structuring network appears to exemplify a form of crisis-information-seeking behaviour, as observed in other contexts (e.g. Heverin and Zach, 2011; Krakowska, 2020), though here it occurs in a situation where authoritative sources were not yet clearly established. In the absence of recognised institutional referents, certain local personalities, such as Saïd Hachim, increasingly occupy central positions within the network. This is also consistent with a post-colonial context, in which there may be a degree of mistrust towards authorities and where local actors are more readily cited by local media outlets. Even when the scientific community began organising in 2019 around the creation of Mayotte's Volcanological and Seismological Monitoring Network (REVOSIMA), scientific actors – although present – remained relatively marginal in terms of visibility, often appearing as isolated nodes within the communication network. REVOSIMA itself also remained largely peripheral in the network, even more than 6 months after its establishment. Time appears to have worked against the institution, with information sources and actor networks already well established, making it difficult for REVOSIMA to integrate effectively among them. Nevertheless, the local figure Saïd Hachim progressively introduced scientists from mainland France, as well as from REVOSIMA, into the media discourse while reporting their speeches and mentioning maritime campaigns. However, he himself was rarely cited in return by these actors. His role thus aligns more closely with that of a mediator, facilitating the circulation of scientific information, rather than an alternative expert in direct opposition to institutional authorities, as it has been observed in other studies (e.g. Devès et al., 2022a).

During the examination of who is granted a voice in media coverage, several key observations emerge. Firstly, primary sources of information (often introduced or relayed by other actors quoted in the article) do not necessarily align with journalists' sources. This discrepancy may arise due to limited access to a primary source, as elaborated on earlier (due to geographical distance, time constraints, etc.); the preference for another source deemed more legitimate and more accessible; or implicit or explicit issues of representation (see Carlson, 2009, and Grassau et al., 2021). This opens a window into the newspapers' networks, the hierarchy of their trust, and the perceived legitimacy of interviewed sources. As identified in a qualitative analysis (Devès et al., 2023), scientific actors notably dominate reported speeches, both from the article authors and from third-party actors. Consequently, they are considered the most reliable or, at the very least, the most legitimate to express themselves, even surpassing the authorities responsible for crisis management and civil protection. While other studies have recognised scientists as “bridges” and “focal points” among various actors (Trias et al., 2019), the notable overrepresentation of scientific figures and institutions is noteworthy here. This could be attributed to journalists focusing on short-term issues like hazard descriptions, impacts, and emergency operations (Devès et al., 2019) or the complexities arising from scientific uncertainties requiring focused attention (Valencio and Valencio, 2018). Scientific actors, being perceived as those with knowledge, are considered closest to understanding the phenomenon and are thus positioned to make recommendations (Oreskes, 2019). Apart from scientific personalities and institutions, the analysis indicates that media and institutional actors also benefit from greater media reach for their statements compared to actors from civil society. This proximity of journalists to institutions, as highlighted in other case studies (e.g. Ploughman, 1997; Wintterlin, 2020), and their reliance on the publications of their counterparts when direct sources are unavailable (Coddington and Molyneux, 2023) are common practices. On the other hand, social media sources have a higher share of reported speech than other mass media, reflecting the increasing use of social media as information sources due to their detailed coverage of current events (e.g. Lindsay, 2011; Lecheler and Kruikemeier, 2016), potentially facilitating two-way communication between institutions and the public (Feldman et al., 2016; Kim and Hastak, 2018). Two-way communication has the potential to facilitate cooperative decision-making (Renn, 2009), to draw upon local knowledge in order to improve understanding of field-level dynamics (Lindell et al., 2006), and, in turn, to strengthen public engagement and contribute to the development of trust (Leiss, 1996; Renn, 2009). However, Pourebrahim et al. (2019) argue that this potential is largely underutilised, showing that X (formerly Twitter) is dominated by authorities primarily engaged in one-way communication rather than interacting with their audiences. A more focused analysis would be needed to explore this in the present case. Throughout the coverage, populations in Mayotte and, to a lesser extent, schoolchildren are frequently cited, but as discussed in this qualitative analysis, they are not often the origin of citations, indicating a relatively passive position within the citation network extracted from this dataset. Despite this, the population is central to the network and is cited by numerous actors. In the general imagination, its protection is the reason for the organisation of this network, but its opinion is seldom expressed, even in local media, which tend to apply pre-constructed news templates (Jemphrey and Berrington, 2000). This perpetuates an asymmetrical and hierarchical representation favouring those perceived to hold knowledge (scientists, institutions in charge of civil protection) at the expense of the inhabitants' perspective, who find themselves in the position of being subjected to the crisis and being protected (Valencio and Valencio, 2018; Gonzalez et al., 2022). Journalists' common practices make it challenging for them to distance themselves from this representation (Cavaca et al., 2016). This result is explored and assessed for this case study by Devès et al. (2023), who also demonstrate that these representations are integrated by various actors in crisis management, particularly within at-risk populations.

That being said, it is worth underscoring that named individuals hold a significant position in this network. Despite the context where crisis and risk management, as well as communication, is organised and framed by established institutions (ministries, prefectures, town halls, scientific institutions responsible for monitoring), individual sources with clear identities tend to contribute more to reported speech compared to institutions. Specifically, named scientists take the lead over their institutions when examining whose speeches these articles mostly report. Moreover, local personalities are mainly quoted when directly mentioned, while the reverse is true when they are indirectly mentioned. Even in the case of crisis managers, individuals such as the prefect, cabinet director, and ministerial envoys clearly stand out from their respective institutions within the network (see Sect. 4.4). Admittedly, these personalities are often associated with an institution. Oreskes (2019) highlights this aspect in her essay Why Trust Science?, using scientists as an example. She contends that trust in an individual is primarily conferred as a member of a professional community with a shared body of knowledge. Butts et al. (2007) also found that coordinating roles, which include information flow, are influenced by the formal institutional status or position within an organisation. This is compounded by the journalistic practice of conducting interviews, which involves collecting an institution's stance through the discourse of one of its representatives. Individuals act as entry points to information for journalists, relaying the messages of their institutions, colleagues, or, in all cases, a community. Hence, they play the role of hubs, or “guardian nodes”, as mentioned by Flecha et al. (2023). However, this interpretation needs qualification based on interviews with inhabitants, analysed in Devès et al. (2023). On one hand, these interviews highlight the importance, according to Mayotte's inhabitants, of embodying information or words with a name or a face. On the other hand, they reveal a significant distrust towards political and even scientific institutions. In this study, we observed that featuring the director of the local BRGM branch over the national director was prioritised, and even the prefect was featured over representatives of the ministries, although the latter had visited the area. Moreover, the local geographer Saïd Hachim is given prominence over members of the scientific monitoring network, even in situations where they are present during campaigns at sea or interventions with schoolchildren. Similar observations were made in two other independent studies: Cripps and Souffrin (2020), which emphasise a general distrust towards official discourse, and Bedessem et al. (2023), which found confidence in scientists without being able to determine if this extends to trust in their institutions. In such circumstances, one might question whether there exists a gap between the representation of journalists and that of local populations, accentuated by a journalistic bias towards institutions that journalists identify as reliable and easily accessible. Regardless, there is a clear need for proximity – geographical, if not cultural – between sources, given the evident dominance of cited personalities when they are on site. With regard to local personalities in particular, their emergence in press coverage occurs later than for others, perhaps attributable to a search for new sources to compensate for the perceived lack of information on the spot (Fallou et al., 2020). In any case, the overrepresentation of individuals compared to institutions raises questions and warrants further investigation.

This approach (i) offers an overview of the interrelationships between all actors involved in managing this crisis, (ii) highlights specificities linked to the context and media coverage, (iii) reflects implicit representations and bonds of trust between actors, and (iv) visualises the network's dynamics over time and how it is disrupted and reorganised after the occurrence of new events. It could be further refined to incorporate not only the quantitative frequency of actor citations, but also qualitative information indicating whether references in the press discourse are positive, negative, or neutral – thereby offering a more nuanced and precise understanding of their media representation. Furthermore, this approach also aligns with theoretical frameworks discussed in recent studies, which have proven relevant for studying risk and crisis management and governance, such as actor–network theory (ANT) (e.g. Beck and Kropp, 2011; Neisser, 2014; Bielenia-Grajewska, 2020) and assemblage theory (McGowran and Donovan, 2021). This study aligns with this theoretical background in several ways. First, it involves an empirical examination of interrelations and associations among actors operating in a simultaneously complex, uncertain, and ambiguous context. Our perspective on these actors is both relationalist and functionalist: it is the flow of discourse, itself structured by the roles these actors play in relation to one another, which creates and shapes this network. Moreover, these various actors are networks themselves, and they are considered on an equal footing, including the media used to constitute the dataset. This analysis also depicts the dynamic nature of this network and how it can be affected by the emergence of new actors, relationships, arrangements, or any other disruptive element, including non-human factors (see Sect. 4.4). Finally, this study illustrates and enhances our understanding of the patterns of ordering. Its originality lies in the fact that this method is applied not only to study the network of actors in the context of crisis management or governance but also to explore how certain actors (the media) represent information circulation in this crisis management context. The use of actor–network theory (ANT) and assemblage theory is relevant in this approach, considering their application in discussing the role of mobilisation in communication (Bielenia-Grajewska, 2020) and the compatibility of ANT with media theory (Couldry, 2008; Belliger and Krieger, 2017).