the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Factors of influence on flood risk perceptions related to Hurricane Dorian: an assessment of heuristics, time dynamics, and accuracy of risk perceptions

Peter J. Robinson

W. J. Wouter Botzen

Toon Haer

Jantsje M. Mol

Jeffrey Czajkowski

Flood damage caused by hurricanes is expected to rise globally due to climate and socio-economic change. Enhanced flood preparedness among the coastal population is required to reverse this trend. The decisions and actions taken by individuals are thought to be influenced by risk perceptions. This study investigates the determinants that shape flood risk perceptions and the factors that drive flood risk misperceptions of coastal residents. We conducted a survey among 871 residents in flood-prone areas in Florida during a 5 d period in which the respondents were threatened to be flooded by Hurricane Dorian. This approach allows us to assess temporal dynamics in flood risk perceptions during an evolving hurricane threat. Among 255 of the same households, a follow-up survey was conducted to examine how flood risk perceptions varied after Hurricane Dorian failed to make landfall in Florida. Our results show that the flood experience and social norms have the most consistent relationship with flood risk perceptions. Furthermore, participants indicated that their level of worry regarding the dangers of flooding decreased after the near-miss of Hurricane Dorian compared to their feelings of worry during the hurricane event. Based on our findings, we offer recommendations for improving flood risk communication policies.

- Article

(1131 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(565 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Florida is one of the most at-risk states in the United States for hurricanes (Basolo et al., 2017; Klotzbach et al., 2018). Hurricanes such as Katrina in 2005, Sandy in 2012, and Ian in 2022 resulted in catastrophic losses (Bostrom et al., 2018; Conroy, 2022). These losses from hurricanes are rising due to population and economic growth and potentially climate change (Coronese et al., 2019; Knutson et al., 2019; Webster et al., 2005). Given the fact that climate change may increase the frequency of floods induced by hurricanes, residents' efforts to protect themselves and reduce their losses are crucial. Risk reduction strategies, such as evacuation and flood-proofing measures, are important responses to a hurricane threat to avoid damage and loss of life (Basolo et al., 2017; Botzen et al., 2019).

Given the rising hurricane risk, one would expect an increase in hurricane preparedness activities. However, many households are currently underprepared for natural hazards (Basolo et al., 2009; Murti et al., 2014), which may be due to a low perception of risk (Dash and Gladwin, 2007; Lindell and Perry, 2012; Peacock et al., 2005). Moreover, individual perceptions of risk are often at odds with expert estimates of risk (Duží et al., 2017), with some individuals underestimating their risk and others overestimating the risk (Dueñas-Osorio et al., 2012). It is useful to understand how individual flood risk perceptions compare with expert risk assessments and the factors influencing these perceptions to improve flood risk communication strategies and flood risk management policies (Brown and Damery, 2002; Bradford et al., 2012; Senkbeil et al., 2019). For instance, policymakers can adapt current risk communication strategies to enhance support for flood risk reduction measures among the public (Bradford et al., 2012; Peacock et al., 2005).

Most prior analyses of flood risk perceptions associated with a hurricane threat rely on data collected at a single moment using cross-sectional surveys conducted after a hurricane has occurred (Basolo et al., 2017; Burnside et al., 2007; Demuth et al., 2016; Lechowska, 2018; Matyas et al., 2011). However, such an approach may not give adequate insights into risk perceptions during a hurricane threat. Risk perceptions may also vary after the hurricane event, depending on the severity of the experienced impacts. Understanding these dynamics regarding risk perceptions is important since many emergency hurricane preparations are made shortly before a hurricane makes landfall. Additionally, it is often observed that structural adjustments to properties to limit future disaster damage are made shortly after a disaster (Bubeck et al., 2012b). Both emergency preparedness actions taken during a threat and structural damage mitigation actions taken afterwards are likely to be guided by individual risk perceptions, among other factors.

Empirical studies that examine flood risk perceptions during a direct threat of a hurricane making landfall are limited. Exceptions are Meyer et al. (2014) and Botzen et al. (2022). Meyer et al. (2014) documented the dynamics of coastal residents' risk perceptions as hurricanes Isaac and Sandy approached the coasts of Louisiana and New Jersey in 2012 using a real-time survey. Botzen et al. (2022) utilised a real-time hurricane survey approach at the end of the 2020 hurricane season to study the evacuation intentions and behaviour of coastal households in Florida. They compared these findings with evacuation intentions at the beginning of the hurricane season using a cross-sectional survey. However, neither Meyer et al. (2014) nor Botzen et al. (2022) offered an analysis of the factors influencing flood risk perceptions, as is done in our study.

The objectives of our study are to understand the temporal dynamics in flood risk perceptions shortly before a hurricane makes landfall and afterwards and to obtain insights into the factors that relate with these risk perceptions, including how they compare with objective indicators of the risk respondents faced at the time of the survey. Our study analyses data collected during the period in which Hurricane Dorian approached Florida in 2019 using a real-time survey. By resurveying part of the original sample a few months after the storm, our paper also contributes to the flood risk perception literature by exploring these dynamics in the context of a near-miss hurricane event. Research on near-miss hurricanes has shown that people may underestimate the dangers of subsequent hazardous situations based on the experience of the near-miss, reasoning that the negative outcome did not materialise last time (Dillon et al., 2011; Dillon and Tinsley, 2016). These insights have been collected through vignette surveys, which are based on hypothetical scenarios. Our research goes beyond these previous studies by examining perceptions in response to a Category 5 hurricane predicted to make landfall in Florida. As such, the main innovation of our study is that we examine how various factors relate with dimensions of flood risk perceptions during an imminent threat of a hurricane as well as changes in these perceptions following an actual near-miss event.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: Sect. 2 provides a theoretical background and our hypotheses about factors related to flood risk perceptions. Section 3 describes the survey and statistical methods. Section 4 presents the results, and Sect. 5 discusses the key findings. Section 6 concludes the paper.

Risk perceptions form an integral part of decision theories in behavioural economics and psychology, which postulate that perceiving a high risk is a necessary condition for taking risk reduction actions (Kahneman and Tversky, 1979; Hertwig and Wulff, 2022). Two thought processes that explain how people perceive and respond to risks are System 1 and System 2 thinking (Kahneman, 2011). The former refers to an intuitive thinking process that operates quickly, effortlessly, and automatically. Furthermore, this mode of thinking has been associated with heuristics. Heuristics are mental shortcuts that simplify the complex reality surrounding risks (Tversky and Kahneman, 1973). By contrast, System 2 considers a more analytical risk assessment by evaluating the available information more systematically and with more effort (Kahneman, 2011). For example, flood likelihood and potential consequences are likely to be assessed by individuals based on information that is available to them.

Since individual perceptions of risk are expected to be shaped by System 1 and System 2, our hypotheses and our explanatory variables are grounded in System 1 and System 2 thinking. In the section below, we describe the heuristics from which the hypotheses follow logically. We examine the influence of experience, in line with the availability heuristic, and herding as part of System 1 thinking processes on flood risk perception. The former refers to a type of cognitive bias in which an event's probability is evaluated based on relevant examples that come to mind (Tversky and Kahneman, 1973). The latter, on the other hand, refers to the mirroring of behaviour of other individuals. In the case of a highly uncertain or risky issue, individuals are more likely to mirror behaviour (Kunreuther, 2021). The influence of actual risk and the development of Hurricane Dorian on risk perception is analysed as part of System 2 thinking in our study because accounting for such information in one's judgement about risk takes considerable effort, in contrast to the heuristic-based judgements that guide System 1 thinking processes.

2.1 Heuristics (System 1)

Consistent with the availability heuristic, a substantial amount of literature has found that previous experience with a flood positively impacts the perceived flood probability as exposure to a flood may make the risk easier to recall and more salient (Bradford et al., 2012; Peacock et al., 2005; Reynaud et al., 2013; Richert et al., 2017). Therefore, we expect that past flood experience has a positive relationship with flood risk perceptions.

- H1.

-

Respondents who have experienced a flood have a higher perception of flood risk.

In addition to actual experience, and consistent with the availability heuristic, we argue that the perception of specific characteristics and risks associated with a hazard, at one moment in time when the hazard is salient, may make it cognitively easier to judge that similar experiences regarding the hazard and its associated risks in general can occur in the future. In the case of Dorian, people faced the possibility of catastrophic damages and developed risk perceptions, such as perceptions about the strength and severity of possible impacts. Individuals with high perceptions of these specific hurricane characteristics may find future hurricane hazards, including their induced flooding, easier to imagine. Thus, we expect high perceptions of specific hurricane characteristics (awareness of living in a Dorian impact area and the perceived hurricane wind speed on the Saffir–Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale) to increase perceived flood risk.

- H2.

-

Respondents with a high perception of specific Dorian characteristics have a higher perception of flood risk.

In a situation where individuals lack objective information regarding a hazard, they may depend on local government officials responsible for risk management instead. This might be the case in our context if people were unaware of information on risk or were unwilling to incur search costs associated with collecting information on risk (Kunreuther and Pauly, 2004). Previous studies have found that individuals distrusting local government officials in charge of flood risk management have a higher perception of risk regarding natural hazards (Siegrist et al., 2005). Terpstra (2011) has shown that respondents who trust local flood risk management assess flood probabilities as lower. Hence, we expect that trust in the capabilities of local government officials responsible for flood risk management lowers flood risk perceptions.

- H3.

-

Respondents who have more trust in the flood management capabilities of local government officials have a lower perception of flood risk.

Few household survey studies have examined social factors as a driver of risk perceptions (Lechowska, 2018; Van der Linden, 2015). We elicit the prescriptive dimension of social norms in our study (Cialdini et al., 1991). Prescriptive social norms in the context of hurricane-induced floods can be defined as the degree of social pressure an individual feels to view floods as a risk that requires action (Van der Linden, 2015). It is hypothesised that individual risk perceptions are amplified if social referents (friends, family, and acquaintances) view an event as a risk that should be acted upon (Swim et al., 2009).

- H4.

-

Respondents who acknowledge that important social referents believe that someone in their (the respondent's) situation ought to act upon the risk of floods have a higher perception of flood risk.

2.2 Objective risk characteristics (System 2)

In line with System 2 thinking, previous studies have found a positive relationship between indicators of actual flood risk and flood risk perception (Botzen et al., 2015; O'Neill et al., 2016; Richert et al., 2017; Rufat and Botzen, 2022). As such, we expect the flood probability at one's residence to be positively related to flood risk perception. Furthermore, we expect that the floor of one's residence influences perceived flood risk because those living on lower floors are more exposed to flood water than people residing on upper floors (Lechowska, 2018). A similar reasoning holds for people who reside in homes with a basement. Overall, we expect the presence of residence characteristics that signal a high exposure to flooding to be positively associated with perceptions of flood risk.

- H5a.

-

Respondents whose homes are situated in an area with a high flood risk have a higher flood risk perception than those whose homes are situated in an area with a lower flood risk.

- H5b.

-

Respondents who occupy the ground floor at their home have a higher perception of flood risk than those who live on an upper floor.

- H5c.

-

Respondents with a basement, cellar, or crawlspace in their home have a higher flood risk perception than those who do not have a basement, cellar, or crawlspace in their home.

The flood risk caused by a hurricane making landfall varies as the characteristics of a hurricane develop over time (Musinguzi and Akbar, 2021). Risk communication strategies regarding flood risk aim to raise awareness and conform risk perceptions to the objective risk that residents face as the risk evolves (Kellens et al., 2013). In the case of Hurricane Dorian, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) informed inhabitants in real-time, as the hurricane was approaching the coast of Florida, about the current level of hurricane intensity. We expect high flood risk perceptions within periods in which the storm's wind speed was high. Furthermore, it has been observed that perceived risk, especially the sense of danger, is likely to decrease after a near-miss of catastrophic damages (Baker et al., 2009). In the context of a near-miss situation, people may assume that they escaped the danger and perceive the intervening good fortune as an indicator of resiliency (Dillon et al., 2011; Tinsley et al., 2012). In addition, risk perceptions are likely to be high during the imminent threat of a hurricane as flood risk is likely to be salient. As a result, we expect the level of worry and concern to decline between the period during the threat of Hurricane Dorian and after the threat had dissipated.

- H6.

-

Respondents who finished the survey during time periods in which the maximum wind speed of Hurricane Dorian was high have a higher flood risk perception.

- H7.

-

During a direct threat of a hurricane, respondents have a higher flood risk perception compared to when this threat has dissipated.

2.3 Individual preferences

Besides heuristics and objective risk characteristics, personal characteristics such as risk preferences have been identified as shaping risk perception (Feyisa et al., 2023; Villacis et al., 2021). In economic theories of decision-making, risk preferences refer to the willingness of an individual to face a potentially risky situation (Feyisa et al., 2023). Negative attitudes may result in an elevated view of risk levels, such as the probability of loss (Prince and Kim, 2021). Therefore, we expect this individual preference to be positively associated with perceived flood risk. Risk aversion is explicitly modelled as a determinant of risk perception, as implemented in studies such as Cullen et al. (2018), Feyisa et al. (2023), and Villacis et al. (2021).

- H8.

-

Respondents who are risk-averse have a higher flood risk perception than those who are risk-seeking.

Locus of control may also be associated with risk perception (Breakwell, 2014; Ahmed et al., 2020). Locus of control can be defined as an individual's belief about whether they have control over outcomes in their life (Rotter, 1966). People with an internal locus of control believe that their efforts determine outcomes in their lives. In contrast, those with an external locus of control think that these outcomes are out of their control and often arise due to fate (Rotter, 1966). Since individuals with an internal locus of control may believe they have the propensity to moderate their level of risk, e.g. by taking risk reduction measures, we predict that they are less likely to worry about risk than people with an external locus of control.

- H9.

-

Respondents with an internal locus of control have a lower flood risk perception than those with an external locus of control.

3.1 Survey instrument and implementation

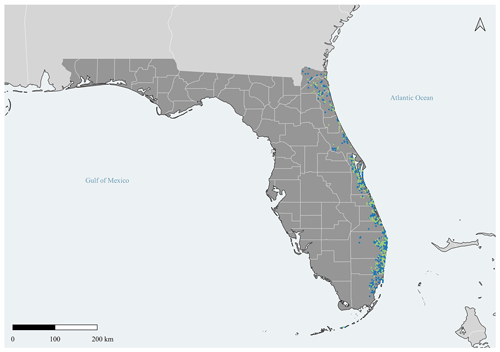

The real-time survey was conducted from the evening of 29 August until 2 September 2019. In total, 871 responses were collected using telephone interviews. The interviews were administered by the company Downs & St. Germain, had a response rate of 12 %, and lasted 20 min on average. All participants were residents of Florida living in potential flood areas based on the FEMA flood zone maps. The sampled respondents lived in neighbourhoods that were forecasted by the National Hurricane Centre to be hit by Hurricane Dorian (National Hurricane Center, 2019). While the projected path of Dorian remained uncertain during the 5 d survey period, the survey sample was updated over time to include areas where flood impacts were expected to be the largest. Figure 1 shows the geographical distribution of survey respondents.

Figure 1Locations of respondents in Florida in our initial survey (in blue dots) and follow-up survey (in green dots).

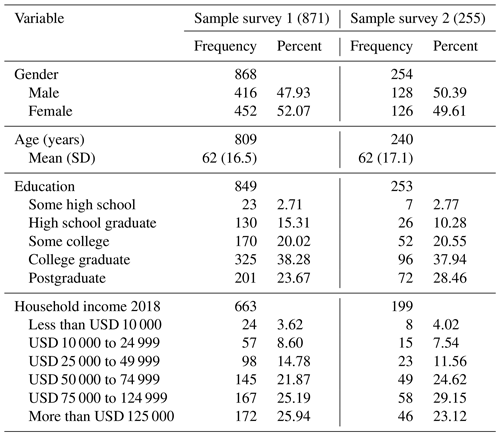

The second survey was administered several months after the near-miss of catastrophic damages from Dorian, among the first survey sample, in order to analyse how risk perceptions at the individual level changed after Hurricane Dorian. Particular care was taken to ensure similar sample characteristics across surveys to meaningfully compare samples in the analysis. Responses were collected using both phone interviews and online questionnaires. Participants who completed the second survey were offered a payment of USD 20. This amount was raised to USD 50 to increase the survey response rate. Non-responders were reminded through a postal mail letter in which they were also informed of the monetary incentive. In total, 255 responses were collected. The sample's main socio-demographic characteristics are similar across the two surveys (see Table 1).

The gender distribution of the first survey is comparable to that of the population of the coastal counties. However, individuals over the age of 65 are overrepresented in the sample, as 49 % of the respondents are 65 years and over compared to the 24 % of citizens in the coastal counties in Florida in 2020 (U.S. Census Data, 2020c). Furthermore, the sample is skewed towards respondents with a college degree or higher (62 %) compared to the coastal population (23 %) (U.S. Census Data, 2020a). Lastly, the median annual gross household income range is USD 100 000, which is higher than the USD 62 600 median household income of the coastal counties after tax (U.S. Census Bureau, 2020b).

3.2 Measures

3.2.1 Dependent variables of general flood risk perceptions

A total of four measures were used to elicit subjective judgements about flood risk: two qualitative questions regarding feelings about risk and two quantitative predictions of the flood probability and the cost to repair damage in the case of a flood. The coding of these variables can be found in Table S1 in the Supplement. The quantitative question regarding the flood probability asked respondents to judge the yearly likelihood that a flood would occur at their homes on a logarithmic scale. Bruine de Bruin et al. (2011) and Woloshin et al. (2000) observed that a logarithmic answer design performs well in eliciting the perception of low likelihood risks. Furthermore, we asked participants to indicate how worried they felt about the danger of a flood at their home and indicate their feelings of concern about the consequences of flooding (following Botzen et al., 2015; Robinson and Botzen, 2018, 2019).

3.2.2 Independent variables

With regard to the independent variables, a range of socio-demographic information was collected, including respondents' gender, age, education, income, and home ownership. The coding of these and the other independent variables can be found in Table S1.

One question was used to assess prior experience with flooding due to natural disasters. Respondents were asked to recall how often their current home had been flooded during the time they had lived there. To measure trust, we asked respondents to indicate how much they felt they could trust the flood limiting capabilities of local government officials on a four-point Likert scale anchored from 1 (not at all) to 4 (completely). Furthermore, we asked respondents two questions about the extent to which they felt social pressure regarding the purchase of flood insurance and the implementation of risk reduction measures on a five-point Likert scale anchored from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Two questions were used to assess Dorian-specific risk perceptions. One question asked respondents to assess their level of certainty that the area they lived in would be affected by Hurricane Dorian. Respondents were also asked to report the wind speed of Hurricane Dorian on the Saffir–Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale based on the last time they received this information.

With regard to objective flood risk, three questions were asked to respondents to elicit the characteristics of their residence. Specifically, we inquired whether part of the building the participant occupied included the ground-floor level and about the presence of a basement, cellar, or crawlspace in the home. Furthermore, we gathered spatial information regarding objective flood risk using FEMA flood zone maps and respondents' ZIP Codes. This information allowed us to geospatially classify the location of participants as either living within a 100-year flood zone (FEMA Zone A) or outside of a 100-year flood zone.

Lastly, regarding individual preferences, both locus of control and risk preferences were elicited using an 11-point Likert scale. Respondents had to indicate how much they felt in control over their lives and how much risk in general they were willing to take. This qualitative survey question to elicit willingness to take risks in general has been shown to predict risk-taking behaviour across different contexts (Dohmen et al., 2011).

3.3 Statistical analysis

3.3.1 Flood risk perceptions

We estimated various ordered logistic regression models to assess the impact of the independent variables on each of the flood risk perception dimensions. The ordinal nature of the dependent variables is accounted for using this method (Liddell and Kruschke, 2018). The general specification can be defined as follows:

where flood risk perception Y of an individual depends on a vector of socio-demographic characteristics of the individuals (S), heuristics (H), objective risk variables (O), and individual preferences (I). For each independent variable the assumption of proportional odds applies, meaning that the coefficient estimate β is the same across logit equations for the different cut points for categories j (Fullerton, 2009).

A series of correlation tests of the explanatory variables were run to analyse multicollinearity. Taking 0.6 as a threshold value from the commonly recommended threshold range of 0.6–0.8 (Tay, 2017), social norms regarding risk mitigation and insurance were found to be highly correlated (r=0.643). As a result, we created a new variable by synthesising the observations of these two variables (Cronbach α=0.779) into one. The reason is that the high correlation implies that the two questions measure the same underlying construct, i.e. a tendency to comply with social norms.

3.3.2 Change in flood risk perceptions

Paired sample t tests were performed to identify differences in the risk perception dimensions during Hurricane Dorian and afterwards. Furthermore, logit regressions were applied to examine determinants of changes in the perceptions of risk. Change variables were calculated by subtracting the observations of the first survey from the observations of the second survey for each risk perception dimension. Thus, the dependent variable Yi in the model is a dummy variable representing negative change (excluding positive change) or positive change (excluding negative change) in the risk perception of individual i, with the reference category indicating no change in risk perception. Independent variables were chosen for inclusion if they remained constant across individuals, in other words, if they were unaffected by the near-miss of Hurricane Dorian, namely socio-demographic variables, residence characteristics, and flood experience. The socio-demographic and residence characteristics were only measured in the first survey, as significant changes were not anticipated.

3.3.3 Flood risk misperceptions

Respondents were classified into groups that either underestimated, correctly estimated, or overestimated the risk. To do so, we compared the subjective valuation (SV) for the three different risk dimensions of each participant with the objective valuation (OV), allowing the error margins (EMs) to differ according to previous studies regarding perceptions of flood risk (Botzen et al., 2015; Mol et al., 2020). Therefore, we consider the perceived risk estimate to be accurate when . The error margin for the perceived flood probability and hurricane wind speed is anchored at 0 %, while the error margin for perceived flood damage caused by Hurricane Dorian is fixed at 50 %. The error margin of 0 % was chosen for perceived flood probability and hurricane wind speed because the objective estimates, the FEMA flood zones, and the Saffir–Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale represent distinct categories. As a result, the estimates of respondents are either regarded as correctly estimating the category or not. The modelled flood damage data, on the other hand, are continuous, and, as such, an interval was chosen for the error margin to reflect flood damage model uncertainty.

The objective flood damage was derived using a model cascade: firstly, the actual storm track of Hurricane Dorian was obtained from NOAA (Historical Hurricane Tracks, 2019). The storm track was then translated into a spider web format using Delft3D software, which provided spatially explicit meteorological data, speed, and direction for the hurricane (Deltares, 2024). The spider web data were used to force the Delft3D Flexible Mesh to obtain inundation depths for all respondent locations. The inundation depths were all translated into a damage fraction using HAZUS depth damage curves (FEMA, 2013). Finally, by multiplying the reported value of the houses by the damage fraction, an objective estimate of flood damage were obtained per respondent.

In order to investigate the drivers of flood risk misperception, two logit regressions for each risk indicator were estimated. The dependent variable Yi in the model is a dummy variable depicting underestimation (excluding overestimation) or overestimation (excluding underestimation) of the risk dimensions of individual i. For all models, the reference category is a correct estimation by the participants.

4.1 Descriptive statistics of risk perceptions

During the first day of the survey the forecast indicated that Hurricane Dorian was predicted to make landfall in the middle of the east coast of Florida, with the uncertainty cone covering almost the entire state. Midway through the survey period, landfall in Florida was still likely, but the hurricane was expected to turn away from the coast over time. On the last day of the survey, the predicted rightward shift became stronger (National Hurricane Center, 2019). However, landfall in Florida was still within the cone of uncertainty. Furthermore, hurricane and flood warnings were issued along the coastline of Florida during the entire duration of data collection (National Hurricane Center, 2019). As a result, respondents faced the threat of suffering flood damage from Hurricane Dorian during the entire time the survey was conducted.

It is notable that almost all participants had heard of the approaching hurricane (92 %), of which the majority correctly indicated that Dorian was a hurricane (93 %) instead of a tropical storm (6 %). A small proportion of the sample stated that they did not know whether Dorian was a hurricane or tropical storm (1 %). Nevertheless, 1 in 4 participants were unaware that they lived in an area that could be affected by the hurricane.

Moreover, almost all respondents in the second survey indicated that their primary source of information to stay updated about the approaching hurricane was the television (91 %). In contrast, social media and face-to-face communication were less commonly utilised. Only 3 % of respondents used Instagram or Twitter, while 18 % used Facebook to gather information about Dorian. Respondents who followed specific social media accounts to acquire information about the storm mainly followed the weather channel (14 %).

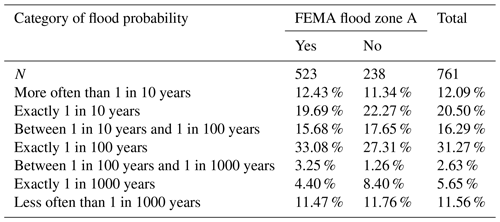

In addition, there is a high perception of the flood probability among respondents (Table 2). In total, 80 % of respondents expect a yearly flood probability of 1 in 100 or more frequently at their home. Furthermore, the majority of the participants (81 %) who live in the 100-year floodplain reported a flood probability of 1 in 100 or more frequently, which shows that many respondents' flood risk perceptions align with the relatively high flood risk they face in reality.

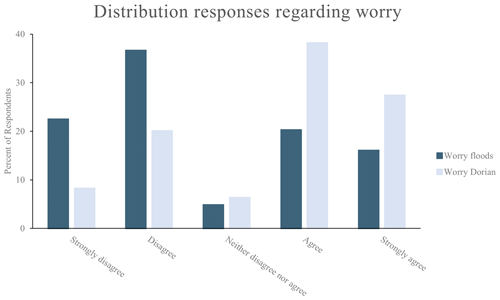

However, this awareness does not result in feelings of concern about flooding, as a majority of respondents believed that the flood probability at their home was too low to be concerned about the consequences of a flood (54 %). Similarly, the majority of the sample indicated that they strongly disagreed or disagreed with the statement “I am worried about the danger of a flood at my current residence” (59 %) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2Distribution of responses to statements about worry of general flood damage and damage caused by Hurricane Dorian.

While the majority of the sample stated that they did not feel generally worried about the danger of a flood at their residence, feelings of worry with regard to possible damage caused by Dorian specifically were present to a greater extent. Only 28 % of the respondents indicated that they strongly disagreed or disagreed with the statement concerning feelings of worry about the hurricane causing damage to their home or home contents. As such, respondents were more worried about damages caused by the approaching hurricane (65 %) than flooding in general (36 %).

4.2 Regression analysis

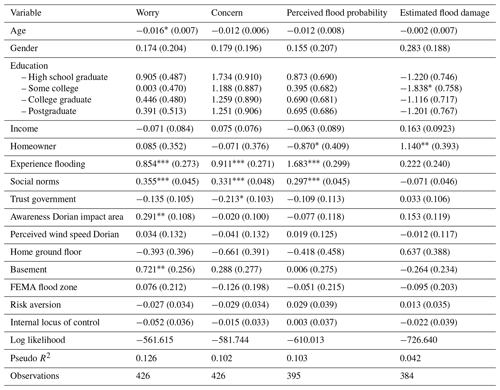

Flood risk perception is measured using four indicators in this study, namely worry about flooding, concern regarding flood consequences, perceived flood probability, and the estimated cost to repair damage in the case of a flood. We present the results of the models for each dimension of flood risk in Table 3. Time-fixed effects are included in the estimations, but we suppress those coefficient estimates in the interest of conserving space.

Table 3Ordered logistic regression model of variables of influence on flood risk perception dimensions.

Notes: time dummy variables are suppressed. Robust standard errors in parentheses. Significance levels: * p<0.05; p<0.01; p<0.001.

Regarding socio-demographic variables, the predictor age is significantly correlated with worry. The negative coefficient for age indicates that older people are less likely to be worried about the dangers of flooding at their current residence compared to younger people. Moreover, the negative coefficient for completion of some college indicates a lower damage estimate. Home ownership has a statistically significant impact on perceived flood probability and estimated flood damage.

We find a strong effect of flood experience and social norms across models. With the exception of estimated flood damage, flood experience and social norms were found to be statistically significant in estimating the level of worry, concern, and perceived flood probability. The positive coefficient on the flood experience variable implies that those who have experienced flooding as a result of natural disasters are more likely to worry about flooding, feel concerned about flood consequences at their home, and have a higher perception of the flood probability compared to those who have not experienced flooding at their current residence. In addition, trust was found to be negatively correlated with the level of concern. That is, those who trust the ability of government officials to limit flood risk are less likely to feel concerned regarding the flood probability at their homes.

With the exception of worry, we find no effect for respondents' awareness of living in an area that was expected to be affected by Hurricane Dorian on flood risk perception. Respondents who indicated that they were certain that the area they live in is expected to be affected by Hurricane Dorian are more likely to feel worried about the dangers of floods at their residence compared to respondents who were not sure whether they live in an area that might be affected by the hurricane.

With regard to housing characteristics, the presence of a basement, cellar, or crawlspace in one's house is significantly related to the level of worry but not to the level of concern, perceived flood probability, and estimated flood damage.

The regression models including the time-fixed effects can be found in the Supplement (Table S2). Time dummy variables, referring to the time and date within which respondents finished the survey categorised by when maximum sustained wind speeds were published by the National Hurricane Centre, concerning the second and third days of the survey period, are significant in estimating levels of worry and concern. Participants who completed the survey during time periods which have significant coefficient estimates have an increased likelihood of feeling worried and concerned about the dangers and consequences of flooding compared to participants who completed the questionnaire at the very beginning of the data collection.

Regarding the individual characteristic variables, we find no relationship between risk aversion and flood risk perceptions or between internal locus of control and flood risk perceptions.

4.3 Differences in risk perception before and after the hurricane threat

Paired sample t tests were performed to determine whether flood risk perceptions changed significantly during and after the threat of Hurricane Dorian. Most changes in flood risk perception are statistically insignificant, except for feelings of worry about the dangers of flooding. The mean decreased from 2.6 to 2.4 (p=0.017), suggesting that worry regarding flooding is higher during periods of extreme weather in line with our hypothesis.

With regard to the explanatory variables, all changes in personal beliefs and experiences are statistically insignificant. Significant changes are observed for the individual preference variables. The mean of risk aversion decreased from 3.9 to 2.8 (p<0.001). This implies that during the hurricane threat people were more risk-averse, which is not surprising in the context of an emergency situation. Locus of control, on the other hand, slightly increased. However, the change in means was not found to be statistically significant.

Exploratory regression analysis

Furthermore, we looked at potential predictors regarding the change in the risk perception dimensions (Table S3, in the interest of conserving space). With the exception of flood experience and education, we find no effect of the independent variables on the change in flood risk perception before and after Hurricane Dorian. Experience of a flood increases the likelihood of feeling less worried and concerned about the dangers and consequences of a flood at respondents' residences after Dorian. Respondents who have completed a higher level of education are less likely to feel a lower level of concern about the flood consequences after Dorian.

4.4 Objective risk assessment

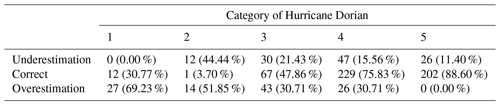

As can be seen in Table 4, the majority of participants overestimated the wind speed of the hurricane while it was a Category 1 or 2 hurricane. Furthermore, the majority of respondents either underestimated or overestimated the wind speed of Dorian while it was a Category 3 hurricane. As such, most of the misperceptions occurred while the hurricane wind speed was low. In contrast, during the 3 d period in which Dorian developed into a Category 4 and 5 hurricane, the majority of respondents correctly estimated the wind speed of the storm. In total, 115 participants (16 %) underestimated the wind speed of Hurricane Dorian, 511 participants (69 %) correctly estimated the hurricane category, and 110 participants (15 %) overestimated the strength of Dorian.

Table 4Distribution of hurricane wind speed estimates on the Saffir–Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale per day (at 0 % error margin).

With regard to the perceived yearly flood probability at the residence of respondents, 423 (60 %) participants correctly stated that they lived in an area with a flood probability of 1 in 100 years or less. In total, 287 participants either underestimated or overestimated the probability of a flood. More precisely, 100 participants (14 %) considered the recurrence interval of a flood at their current residence as less frequent than 1 in 100 years even though they live in FEMA flood zone A, thereby underestimating the flood probability. A total of 187 (26 %) participants, on the other hand, overestimated the flood probability at their current residence, estimating the return period as 1 in 100 years or more frequent while living outside the 1 in 100 years flood zone.

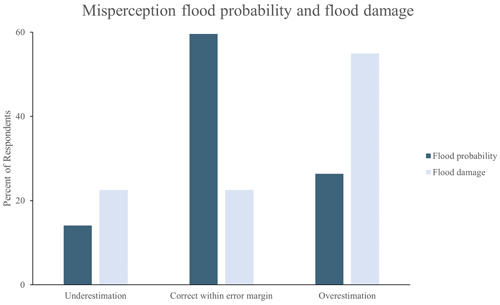

Figure 3 provides an overview of the distribution of underestimations, correct estimations, and overestimations for anticipated flood damage. The vast majority of respondents, namely 356 participants (55 %), overestimated the cost to repair the damage to their home and its contents in the case of a flood.

Figure 3Distribution underestimations, correct estimations, and overestimations for anticipated flood probability (EM = 0 %) and damage (EM = 50 %).

Exploratory regression analysis

Table S4 (in the interest of conserving space) reports regression results for the three dimensions of flood risk perception. The negative coefficient for the variable concern indicates that respondents who perceive the flood probability as sufficiently high to be concerned about the consequences of a flood are less likely to underestimate the flood probability. In addition, those who are concerned are less likely to underestimate potential flood damage, while those who are risk-averse are more likely to overestimate the damage.

With regard to residence characteristics, the positive coefficient for the ground floor indicates that individuals who live on the ground floor are more likely to overestimate the flood probability at their home. This result makes sense, since individuals who live on the ground floor are more at risk regarding floods.

Regarding personal preferences, being risk-averse makes it more likely that respondents will overestimate the cost to repair their home and home contents in the case of a flood. In other words, the more risk-averse respondents are, the more pessimistic they are in estimating the cost to repair the damage to their home caused by a flood.

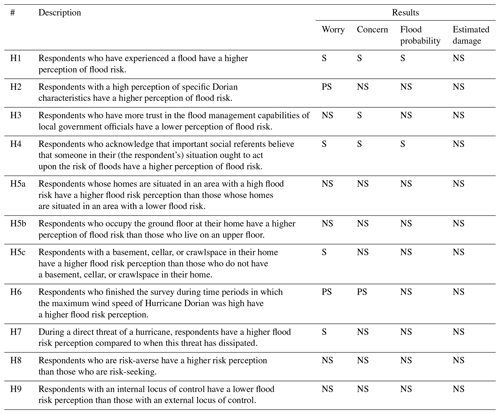

The results described in Sect. 4 concerning our hypotheses are summarised in Table 5. Overall, flood experience and social norms are the most consistent predictors of flood risk perception. Numerous studies have observed the role experience plays in shaping flood risk perception (Bubeck et al., 2012a; Lechowska, 2018). In contrast, few papers discuss the role of socio-cultural context, which includes the influence of social norms, in relation to flood risk perceptions (Lechowska, 2018), which we find to be a key explanatory variable.

Table 5Summary of hypotheses.

Notes: S is supported, PS is partially supported, and NS is not supported.

The results are consistent with the availability heuristic (H1) in line with previous research (Bradford et al., 2012; Botzen et al., 2015; Peacock et al., 2005; Reynaud et al., 2013; Richert et al., 2017; Rufat and Botzen, 2022). Our assessment shows that the experience of a flood significantly and positively influences the flood risk perception dimensions of worry, concern, and perceived flood probability but not estimated damage. The latter effect may be explained by the previously experienced floods not resulting in substantial damage. Furthermore, our findings provide additional insights to the literature on the availability heuristic in flood risk perception. We find that a direct flood experience influences flood risk perceptions to a greater extent than a high perception of specific hazard characteristics does (H2). This result indicates that the experience of flooding matters regarding the availability heuristic, rather than being in a situation where the flood hazard is salient.

In addition, our findings do not strongly support the negative effect of trust on flood risk perceptions (H3). Previous research has suggested that higher levels of trust reduce perceptions of flood risk (Siegrist et al., 2005; Terpstra, 2011). While trust concerning government officials and their capability to limit flood risk negatively relates to concern regarding flood consequences in our study, we find no significant effect of trust on the other flood risk perception dimensions.

Social norms, on the other hand, are strongly related to risk perceptions. We find that the variable social norms relate positively and significantly to worry regarding flooding, concern regarding flood consequences, and the perceived flood probability, confirming H4. Risk behaviour research in the context of flooding has found similar results (Lo, 2013; Poussin et al., 2014), indicating that individual uptake of flood risk reduction measures is amplified the more social referents recognise and act upon a risk. As such, our results add to the risk perception literature as social norms do not only influence the uptake of flood risk reduction measures, but they are also associated with higher flood risk perceptions.

System 2 thinking processes, which include analytical risk judgements, are also found to influence risk perception. The positive relationship between objective and perceived flood risk is in line with previous literature (Botzen et al., 2015; O'Neill et al., 2016; Richert et al., 2017). With regard to residence characteristics, we find that the presence of a basement is positively related to the level of worry regarding flooding.

Furthermore, we find that the development of the hurricane forecasts concerning the hurricane wind speed has no impact on perceived flood probabilities. This finding suggests that the cognitive assessment of flood risk (flood probabilities) is largely insensitive to shifts in the maximum wind speed. In contrast, feelings about risk (worry and concern) are more susceptible to these changes. We find that worry and concern regarding floods are higher during periods in which the hurricane category is high.

Our data show that after the respondents experienced Hurricane Dorian, all dimensions of risk perception dropped. Previous studies have found similar results, demonstrating that people have a diminished risk perception after facing a near-miss natural hazard (Dillon et al., 2011; Dillon and Tinsley, 2016). However, the current analysis finds only partial support for H7, as worry was the only variable to decrease significantly after Hurricane Dorian. Regarding the explanatory variables, we find a significant decrease in risk aversion after the near-miss of Hurricane Dorian. The decline in risk aversion suggests that in the context of natural hazards risk, preferences vary over time, with individuals being more risk-averse during a direct threat and less risk-averse following a near-miss, rather than being a stable personality trait (Schildberg-Hörisch, 2018).

With regard to the over- and underestimation of risk dimensions, many respondents have accurate perceptions of the risks they face. Most respondents correctly recalled the maximum wind speed of Hurricane Dorian, especially when it was high (Category 4 of 5), but overestimated it when the wind speed was low (Category 1 or 2). These results may indicate an enhanced communication of, or interest in, the risk as Dorian proceeded to rapidly intensify by 1 September. Similarly, most of the respondents correctly perceived the flood probability at their homes. The overall correct estimation of the flood probability is in contrast to some previous work (Botzen et al., 2015; Mol et al., 2020). Floods are much more frequent in Florida compared with the areas focused on in these previous studies, which may explain a more rational appraisal of the flood probability in Florida. Regarding the estimated damage, more respondents overestimated (55 %) than underestimated (23 %) the cost to repair damage in the case of a flood. The results show that being risk-averse contributes to this overestimation. Respondents who think that the flood probability is above their threshold level of concern, on the other hand, are less likely to underestimate the cost of repairing the damage to their home and home contents in the case of a flood. This result is consistent with the findings of Botzen et al. (2015), who found that individuals who assessed the flood probability to be below their threshold level of concern are more likely to underestimate their flood damage.

Policy implications

Our results show that misperceptions prevail. As many as 1 in 4 participants incorrectly perceived themselves as living in an area that could not be impacted by Hurricane Dorian. Furthermore, we find that most people overestimated the wind speed of Hurricane Dorian when it was low (Category 1 or 2). These misperceptions show the importance of improving risk communication strategies, especially in cases where risk perceptions are significantly lower than objective risk. Risk communication during a storm can be improved by spreading more information about the storm and the areas it can affect to the inhabitants of these areas. Furthermore, we find that flood risk perceptions are high during an imminent hurricane threat. Periods in which risk perceptions are more likely to be high are suitable moments to motivate and inform people about appropriate dry and wet flood-proofing measures using risk communication campaigns (Botzen et al., 2020; Bubeck et al., 2012a). Therefore, communication policies during a hurricane threat should not only focus on the risk itself but also on the risk reduction measures people can implement during times of heightened risk perceptions.

Based on our results, we recommend that raising awareness and activating social norms should be the focus of these campaigns. The decline in worry regarding the dangers of a flood, in combination with the strong influence of previous flood event experience on flood risk perception, highlights the need to preserve the memory of past floods. Enlisting the help of those whom inhabitants feel trust for or trust as experts could lead to employing the most influential sources in the communication of flood risk information. However, the effectiveness of activating social norms depends on the careful design of communication messages and is highly context-dependent (Bicchieri and Dimant, 2022; Hauser et al., 2018).

Moreover, promoting flood risk awareness in the absence of a natural disaster is especially important after a near-miss hazard, since our findings show that risk perceptions decline after the near-miss. The uniqueness of each storm should be stressed in communication strategies, with the possibility of a direct hit for each hurricane being taken seriously in order to prevent the underestimation of flooding caused by natural disasters.

Flood damage caused by hurricanes is predicted to continue to increase in the future. Flood preparedness and support of flood risk management policies among the public are needed to reverse this trend. However, empirical studies on household preparedness show that many households are underprepared for hurricane-induced floods, which to a larger extent could be due to low flood risk perceptions. We investigated various determinants of flood risk perceptions and aimed to understand flood risk misperceptions of coastal residents in Florida in order to give recommendations for flood risk communication strategies.

The novelty of our approach can be considered the main addition to the literature, as we employed a real-time and a follow-up survey during and after the threat of Hurricane Dorian. The former allows us to gain a relatively unique and important understanding of flood risk perceptions and their drivers during a period in which the hurricane threat is heightened, while the latter provides a longitudinal view of the change in risk perceptions after the close call of Hurricane Dorian making landfall in Florida.

Overall, the results show that while there is a high awareness of the flood probability, this awareness does not necessarily translate into a high concern or worry about flooding. However, participants tended to perceive the approaching hurricane as more of a threat with regard to the possible damage caused by Dorian. Still, 1 in 4 participants were unaware that they were living in an area that was predicted to be impacted by Hurricane Dorian. After the near-miss, participants indicated that they felt less worried regarding the dangers of flooding, and risk aversion declined.

Regarding the drivers of the flood risk perceptions, we find that previous flooding experience, in line with the availability heuristic, and social norms have the most consistent influence. The latter result suggests the importance of including socio-cultural context in future flood risk perception studies to approach flood risk perception in a more holistic manner. Furthermore, we observe a significant relationship with various variables associated with the mode of thinking that represents the deliberate and analytical mental process (System 2 thinking) and perceived flood risk, although to a lesser extent than the variables associated with the intuitive thinking process that operates quickly and automatically (System 1 thinking).

Based on our results, the following policy recommendations can be drawn. Information campaigns should aim to preserve the memory of past floods among the population and focus on activating social norms. Furthermore, the observation that worry regarding the dangers of flooding declined after a near-miss shows the importance of regular campaigns promoting risk awareness after a near-miss. In order to prevent the underestimation of flooding caused by hurricanes, each possibility of a direct hit should be taken seriously.

The raw and processed data are not publicly available as the participants of this study did not give written consent for their data to be shared publicly.

The supplement related to this article is available online at: https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-24-1303-2024-supplement.

LAdW: formal analysis, methodology, and writing (original draft preparation and review and editing). PJR: supervision and writing (review and editing). WJWB: conceptualisation, supervision, and writing (review and editing). TH: methodology. JM: methodology and writing (review and editing). JC: data curation.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors.

This research was funded by the State of Florida Division of Emergency Management, the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant no. 101036599 of the REACHOUT project, and EU ERC INSUREADAPT (grant no. 101086783).

This paper was edited by Olga Petrucci and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Ahmed, M. A., Haynes, K., Tofa, M., Hope, G., and Taylor, M.: Duty or safety? Exploring emergency service personnel's perceptions of risk and decision-making when driving through floodwater, Progress in Disaster Science, 5, 100068, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pdisas.2020.100068, 2020.

Baker, J., Shaw, W. D., Riddel, M., and Woodward, R. T.: Changes in subjective risks of hurricanes as time passes: Analysis of a sample of Katrina evacuees, J. Risk. Res., 12, 59–74, 2009.

Basolo, V., Steinberg, L. J., Burby, R. J., Levine, J., Cruz, A. M., and Huang, C.: The effects of confidence in government and information on perceived and actual preparedness for disasters, Environ. Behav., 41, 338–364, 2009.

Basolo, V., Steinberg, L. J., and Gant, S.: Hurricane threat in Florida: examining household perceptions, beliefs, and actions, Environ. Hazards-UK, 16, 253–275, 2017.

Bicchieri, C. and Dimant, E.: Nudging with care: The risks and benefits of social information, Public Choice, 191, 443–464, 2022.

Bostrom, A., Morss, R., Lazo, J. K., Demuth, J., and Lazrus, H.: Eyeing the storm: How residents of coastal Florida see hurricane forecasts and warnings, Int. J. Disast. Risk. Re., 30, 105–119, 2018.

Botzen, W., Robinson, P. J., Mol, J. M., and Czajkowski, J.: Improving individual preparedness for natural disasters: Lessons learned from longitudinal survey data collected from Florida during and after Hurricane Dorian, Institute for Environmental Studies – Vrije Universiteit, Amsterdam, 2020.

Botzen, W. W., Kunreuther, H., and Michel-Kerjan, E.: Divergence between individual perceptions and objective indicators of tail risks: Evidence from floodplain residents in New York City, Judgm. Decis. Mak., 10, 365–385, 2015.

Botzen, W. W., Kunreuther, H., Czajkowski, J., and de Moel, H.: Adoption of individual flood damage mitigation measures in New York City: An extension of Protection Motivation Theory, Risk. Anal., 39, 2143–2159, 2019.

Botzen, W. W., Mol, J. M., Robinson, P. J., Zhang, J., and Czajkowski, J.: Individual hurricane evacuation intentions during the COVID-19 pandemic: insights for risk communication and emergency management policies, Nat. Hazards, 111, 507–522, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-021-05064-2, 2022.

Bradford, R. A., O'Sullivan, J. J., van der Craats, I. M., Krywkow, J., Rotko, P., Aaltonen, J., Bonaiuto, M., De Dominicis, S., Waylen, K., and Schelfaut, K.: Risk perception – issues for flood management in Europe, Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci., 12, 2299–2309, https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-12-2299-2012, 2012.

Breakwell, G. M.: The psychology of risk, Cambridge University Press, https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139061933, 2014.

Brown, J. D. and Damery, S. L.: Managing flood risk in the UK: towards an integration of social and technical perspectives, T. I. Brit. Geogr., 27, 412–426, 2002.

Bruine de Bruin, W., Parker, A. M., and Maurer, J.: Assessing small non-zero perceptions of chance: The case of H1N1 (swine) flu risks, J. Risk. Uncertainty, 42, 145–159, 2011.

Bubeck, P., Botzen, W. J. W., and Aerts, J. C.: A review of risk perceptions and other factors that influence flood mitigation behavior, Risk. Anal., 32, 1481–1495, 2012a.

Bubeck, P., Botzen, W. J. W., Kreibich, H., and Aerts, J. C. J. H.: Long-term development and effectiveness of private flood mitigation measures: an analysis for the German part of the river Rhine, Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci., 12, 3507–3518, https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-12-3507-2012, 2012b.

Burnside, R., Miller, D. S., and Rivera, J. D.: The impact of information and risk perception on the hurricane evacuation decision-making of greater New Orleans residents, Sociol. Spectrum., 27, 727–740, 2007.

Cialdini, R. B., Kallgren, C. A., and Reno, R. R.: A focus theory of normative conduct: A theoretical refinement and reevaluation of the role of norms in human behavior, in Advances in experimental social psychology, Academic Press, 24, 201–234, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60330-5, 1991.

Conroy, J. O.: Flooding, outages, confusion: Florida reels as Hurricane Ian death toll rises, 3 October 2022, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2022/oct/03/hurricane-ian-death-toll-florida (last access: 14 February 2024), 2022.

Coronese, M., Lamperti, F., Keller, K., Chiaromonte, F., and Roventini, A.: Evidence for sharp increase in the economic damages of extreme natural disasters, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA., 116, 21450–21455, 2019.

Cullen, A. C., Anderson, C. L., Biscaye, P., and Reynolds, T. W.: Variability in cross-domain risk perception among smallholder farmers in Mali by gender and other demographic and attitudinal characteristics, Risk. Anal., 38, 1361–1377, 2018.

Dash, N. and Gladwin, H.: Evacuation decision making and behavioral responses: Individual and household, Nat. Hazards. Rev., 8, 69–77, 2007.

Deltares: Delft3D FM Suite 1D2D, Version 2023, https://content.oss.deltares.nl/delft3dfm1d2d/D-Flow_FM_User_Manual_1D2D.pdf (last access: 7 February 2024), 2024.

Demuth, J. L., Morss, R. E., Lazo, J. K., and Trumbo, C.: The effects of past hurricane experiences on evacuation intentions through risk perception and efficacy beliefs: A mediation analysis, Weather. Clim. Soc., 8, 327–344, 2016.

Dillon, R. L. and Tinsley, C. H.: Near-miss events, risk messages, and decision making, Environment Systems and Decisions, 36, 34–44, 2016.

Dillon, R. L., Tinsley, C. H., and Cronin, M.: Why near-miss events can decrease an individual's protective response to hurricanes, Risk. Anal., 31, 440–449, 2011.

Dohmen, T., Falk, A., Huffman, D., Sunde, U., Schupp, J., and Wagner, G. G.: Individual risk attitudes: Measurement, determinants, and behavioral consequences, J. Eur. Econ. Assoc., 9, 522–550, 2011.

Dueñas-Osorio, L., Buzcu-Guven, B., Stein, R., and Subramanian, D.: Engineering-based hurricane risk estimates and comparison to perceived risks in storm-prone areas, Nat. Hazards. Rev., 13, 45–56, 2012.

Duží, B., Vikhrov, D., Kelman, I., Stojanov, R., and Juřička, D.: Household measures for river flood risk reduction in the Czech Republic, J. Flood. Risk. Manag., 10, 253–266, 2017.

FEMA: Multi-hazard loss estimation methodology: Flood model HAZUS: Flood model, HAZUS, Department of Homeland Security, Technical Manual, https://www.fema.gov/flood-maps/tools-resources/flood-map-products/hazus/user-technical-manuals (last access: 7 February 2024), 2013.

Feyisa, A. D., Maertens, M., and de Mey, Y.: Relating risk preferences and risk perceptions over different agricultural risk domains: Insights from Ethiopia, World. Dev., 162, 106137, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2022.106137, 2023.

Fullerton, A. S.: A conceptual framework for ordered logistic regression models, Sociol. Method. Res., 38, 306–347, 2009.

Hauser, O. P., Gino, F., and Norton, M. I.: Budging beliefs, nudging behaviour, Mind & Society, 17, 15–26, 2018.

Hertwig, R. and Wulff, D. U.: A description–experience framework of the psychology of risk, Perspect. Psychol. Sci., 17, 631–651, 2022.

Historical Hurricane Tracks: https://coast.noaa.gov/hurricanes/#map=4/32/-80 (last access: 7 February 2024), 2019.

Kahneman, D.: Thinking, fast and slow, Macmillan, ISBN 9780374533557, 2011.

Kahneman, D. and Tversky, A.: Prospect theory: an analysis of decision under risk, Econometrica, 47, 263–291, https://doi.org/10.2307/1914185, 1979.

Kellens, W., Terpstra, T., and De Maeyer, P.: Perception and communication of flood risks: A systematic review of empirical research, Risk. Anal., 33, 24–49, 2013.

Klotzbach, P. J., Bowen, S. G., Pielke, R., and Bell, M.: Continental US hurricane landfall frequency and associated damage: Observations and future risks, B. Am. Meteorol. Soc., 99, 1359–1376, 2018.

Knutson, T., Camargo, S. J., Chan, J. C., Emanuel, K., Ho, C. H., Kossin, J., Mohapatra, M., Satoh, M., Sugi, M., Walsh, K., and Wu, L.: Tropical cyclones and climate change assessment: Part I: Detection and attribution, B. Am. Meteorol. Soc., 100, 1987–2007, 2019.

Kunreuther, H.: Improving the national flood insurance program, Behavioural Public Policy, 5, 318–332, 2021.

Kunreuther, H. and Pauly, M.: Neglecting disaster: Why don't people insure against large losses?, J. Risk Uncertainty, 28, 5–21, 2004.

Lechowska, E.: What determines flood risk perception? A review of factors of flood risk perception and relations between its basic elements, Nat. Hazards, 94, 1341–1366, 2018.

Liddell, T. M. and Kruschke, J. K.: Analyzing ordinal data with metric models: What could possibly go wrong?, J. Exp. Soc. Psychol., 79, 328–348, 2018.

Lindell, M. K. and Perry, R. W.: The protective action decision model: Theoretical modifications and additional evidence, Risk. Anal., 32, 616–632, 2012.

Lo, A. Y.: The role of social norms in climate adaptation: Mediating risk perception and flood insurance purchase, Global Environ. Chang., 23, 1249–1257, 2013.

Matyas, C., Srinivasan, S., Cahyanto, I., Thapa, B., Pennington-Gray, L., and Villegas, J.: Risk perception and evacuation decisions of Florida tourists under hurricane threats: A stated preference analysis, Nat. Hazards, 59, 871–890, 2011.

Meyer, R. J., Baker, J., Broad, K., Czajkowski, J., and Orlove, B.: The dynamics of hurricane risk perception: Real-time evidence from the 2012 Atlantic hurricane season, B. Am. Meteorol. Soc., 95, 1389–1404, 2014.

Mol, J. M., Botzen, W. W., Blasch, J. E., and de Moel, H.: Insights into flood risk misperceptions of homeowners in the Dutch River Delta, Risk. Anal., 40, 1450–1468, 2020.

Murti, M., Bayleyegn, T., Stanbury, M., Flanders, W. D., Yard, E., Nyaku, M., and Wolkin, A.: Household emergency preparedness by housing type from a Community Assessment for Public Health Emergency Response (CASPER), Michigan, Disaster Med. Public, 8, 12–19, 2014.

Musinguzi, A. and Akbar, M. K.: Effect of varying wind intensity, forward speed, and surface pressure on storm surges of Hurricane Rita, Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 9, 128, https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse9020128, 2021.

National Hurricane Center: DORIAN Graphics Archive: 3-day Forecast Track and Watch/Warning Graphic, https://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/2019/DORIAN_graphics.php?product=3day_cone_no_line (last access: 31 May 2023), 2019.

O'Neill, E., Brereton, F., Shahumyan, H., and Clinch, J. P.: The impact of perceived flood exposure on flood-risk perception: The role of distance, Risk. Anal., 36, 2158–2186, 2016.

Peacock, W. G., Brody, S. D., and Highfield, W.: Hurricane risk perceptions among Florida's single family homeowners, Landscape Urban Plan., 73, 120–135, 2005.

Poussin, J. K., Botzen, W. W., and Aerts, J. C.: Factors of influence on flood damage mitigation behaviour by households, Environ. Sci. Policy, 40, 69-77, 2014.

Prince, M. and Kim, Y.: Impact of risk aversion, reactance proneness and risk appraisal on travel destination risk perception, J. Vacat. Mark., 27, 203–216, 2021.

Reynaud, A., Aubert, C., and Nguyen, M. H.: Living with floods: Protective behaviours and risk perception of Vietnamese households, Geneva Pap. R. I-ISS. P., 38, 547–579, 2013.

Richert, C., Erdlenbruch, K., and Figuières, C.: The determinants of households' flood mitigation decisions in France-on the possibility of feedback effects from past investments, Ecol. Econ., 131, 342–352, 2017.

Robinson, P. J. and Botzen, W. J.: The impact of regret and worry on the threshold level of concern for flood insurance demand: Evidence from Dutch homeowners, Judgm. Decis. Mak., 13, 237–245, 2018.

Robinson, P. J. and Botzen, W. W.: Determinants of probability neglect and risk attitudes for disaster risk: An online experimental study of flood insurance demand among homeowners, Risk. Anal., 39, 2514–2527, 2019.

Rotter, J. B.: Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement, Psychol. Monogr.-Gen. A., 80, 1–28, 1966.

Rufat, S. and Botzen, W. W.: Drivers and dimensions of flood risk perceptions: Revealing an implicit selection bias and lessons for communication policies, Global. Environ. Chang., 73, 102465, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2022.102465, 2022.

Schildberg-Hörisch, H.: Are risk preferences stable?, J. Econ. Perspect., 32, 135–154, 2018.

Senkbeil, J., Collins, J., and Reed, J.: Evacuee perception of geophysical hazards for Hurricane Irma, Weather Clim. Soc., 11, 217–227, 2019.

Siegrist, M., Gutscher, H., and Earle, T. C.: Perception of risk: the influence of general trust, and general confidence, J. Risk. Res., 8, 145–156, 2005.

Swim, J., Clayton, S., Doherty, T., Gifford, R., Howard, G., Reser, J., Stern, P., and Weber, E.: Psychology and global climate change: Addressing a multi-faceted phenomenon and set of challenges. A report by the American Psychological Association's task force on the interface between psychology and global climate change, American Psychological Association, Washington, 66, 241–250, 2009.

Tay, R.: Correlation, variance inflation and multicollinearity in regression model, Journal of the Eastern Asia Society for Transportation Studies, 12, 2006–2015, 2017.

Terpstra, T.: Emotions, trust, and perceived risk: Affective and cognitive routes to flood preparedness behavior, Risk. Anal., 31, 1658–1675, 2011.

Tinsley, C. H., Dillon, R. L., and Cronin, M. A.: How near-miss events amplify or attenuate risky decision making, Manage. Sci., 58, 1596–1613, 2012.

Tversky, A. and Kahneman, D.: Availability: A heuristic for judging frequency and probability, Cognitive Psychol., 5, 207–232, 1973.

U.S. Census Bureau: FIELD OF BACHELOR'S DEGREE FOR FIRST MAJOR, American Community Survey, ACS 5-Year Estimates Subject Tables, Table S1502, https://data.census.gov/table/ACSST5Y2020.S1502?q=education_florida_2020&t=Educational_Attainment&g=050XX00US12009,12011,12031,12035,12061,12085,12086,12087,12089,12099,12109,12111,12127 (last access: 8 January 2024), 2020a.

U.S. Census Bureau: INCOME IN THE PAST 12 MONTHS (IN 2020 INFLATION-ADJUSTED DOLLARS), American Community Survey, ACS 5-Year Estimates Subject Tables, Table S1901, https://data.census.gov/table/ACSST5Y2020.S1901?q=income%20florida%202020&t=Education&g=050XX00US12009,12011,12031,12035,12061,12085,12086,12087,12089,12099,12109,12111,12127 (last access: 8 January 2024), 2020b.

U.S. Census Bureau: PROFILE OF GENERAL POPULATION AND HOUSING CHARACTERISTICS, https://data.census.gov/table/DECENNIALDP2020.DP1?q=Nassau%20County,%20Florida&g=040XX00US12_050XX00US12009,12011,12031,12035,12061,12085,12086,12087,12089,12099,12109,12111,12127&d=DEC%20Demographic%20Profile (last access: 8 January 2024), 2020c.

Van der Linden, S.: The social-psychological determinants of climate change risk perceptions: Towards a comprehensive model, J. Environ. Psychol., 41, 112–124, 2015.

Villacis, A. H., Alwang, J. R., and Barrera, V.: Linking risk preferences and risk perceptions of climate change: A prospect theory approach, Agr. Econ., 52, 863–877, 2021.

Webster, P. J., Holland, G. J., Curry, J. A., and Chang, H. R.: Changes in tropical cyclone number, duration, and intensity in a warming environment, Science, 309, 1844–1846, 2005.

Woloshin, S., Schwartz, L. M., Byram, S., Fischhoff, B., and Welch, H. G.: A new scale for assessing perceptions of chance: a validation study, Med. Decis. Making, 20, 298–307, 2000.