the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Public intention to participate in sustainable geohazard mitigation: an empirical study based on an extended theory of planned behavior

Huige Xing

Ting Que

Yuxin Wu

Shiyu Hu

Haibo Li

Hongyang Li

Martin Skitmore

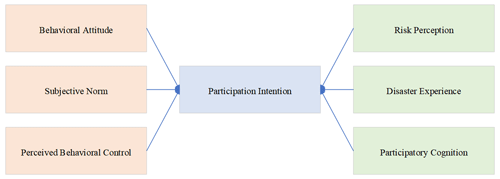

Nima Talebian

Giving full play to the public's initiative for geohazard reduction is critical for sustainable disaster reduction under a government-led top-down disaster governance approach. According to the public's intention to participate in geohazard mitigation activities, this study introduces the analytical framework of the theory of planned behavior (TPB), with attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control as the primary explanatory variables, with three added explanatory variables: risk perception, disaster experience, and participation perception.

Survey data obtained from 260 respondents in Jinchuan County, Sichuan Province, China, are analyzed using structural equation modeling and combined with multivariate hierarchical regression to test the explanatory power of the model. The results indicate that attitude, subjective normative, perceived behavioral control, and participatory cognition are significant predictors of public intention to participate. Disaster experience is negatively associated with public intention to participate. In addition, the extended TPB model contributes 50.7 % to the explanation of the behavioral intention of public participation.

Practical suggestions and theoretical guidance are provided for strengthening geohazard risk management and achieving sustainable disaster reduction. In particular, it is concluded that, while correctly guiding public awareness of disaster reduction activities, policymakers should continue developing participatory mechanisms, paying attention to two-way communication bridges between the public and the government, uniting social forces, and optimizing access to resources.

- Article

(1696 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

Frequent natural disaster events have caused great harm in many aspects, such as economic and social development, people's safety, and environmental ecosystems, among which geohazards are more prominent in mountainous areas where the level of socioeconomic development is lagging and the natural ecological environment is fragile; 80 % of southwestern China's Sichuan Province is in a mountainous environment, and geohazards such as flash floods seriously threaten people's lives and property safety (Gong et al., 2018). According to the National Bureau of Statistics of the People's Republic of China, a total of 160 640 geohazards occurred from 2008 to 2019, causing 9525 casualties and CNY 51.9 billion direct economic losses.

Sustainable development is the theme of today's global development, and the goal of its systematic operation mechanism is to make the Earth system achieve the best structure and function, which means to achieve the organic coordination of economic, social, and ecological benefits under the premise of the relationship between man and nature and the relationship between people, so as to achieve sustainable development (Olawumi and Chan, 2018). The Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction (2015–2030), adopted by the United Nations in March 2015, states that the expected outcome of the framework for the next 15 years is “significant reduction in disaster risk and loss of life, livelihoods and health, as well as the impact of disasters on economic, physical, social, cultural, business, community and national” (Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030, 2015; Peters and Peters, 2021). Preventing new disasters and reducing existing disaster risks, as well as managing residual risks, all contribute to strengthening resilience and thus to achieving sustainable development. Therefore, the human society coexisting with disasters urgently needs to manage disasters effectively from the point of view of sustainable development. Effectively addressing risks and promoting sustainable development needs to be integrated with climate change adaptation (Seidler et al., 2018), resilience strategies (Cwa and Sjc, 2020), resilient communities (Dube, 2020), etc. According to Stephan et al. (2017) the design of disaster risk management measures in line with the concept of social and ecological sustainability contributes to the long-term reduction of social vulnerability and is a major trend for the future, based on disaster science and the sustainability impact of post-disaster measures.

As a fundamental force in disaster risk management, the public is increasingly becoming part of sustainable disaster reduction governance. In sustainable geohazard mitigation, as participants in disaster reduction activities, the public plays a dual role. On the one hand, they need to cooperate with the government and actively participate in disaster preparedness training such as evacuation drills, so as to improve the disaster reduction ability of himself and the whole community. On the other hand, they actively express their opinions when participating in government discussions on the preparation of the plan, based on their own feelings and experiences of participation. Studies have shown that the public actively participates in disaster reduction activities, learns self-help skills and disaster reduction knowledge, formulates effective disaster reduction and household disaster prevention programs, and proactively provides advice to decision-makers according to the actual situation. This two-way interaction helps decision-makers gain access to local knowledge as well as “additional benefits of sustainability and potential behavioural changes” (Roopnarine et al., 2021). Pearce (2003) argues that the organic combination of disaster management, community planning, and public participation can achieve sustainable disaster reduction and governance. The focus of disaster management has shifted from reactive prevention to proactive mitigation and from single actors to multiple participants. From a multistakeholder collaborative perspective, it is also clear that community-based disaster risk reduction is the foundation for the disaster management system pyramid and is critical to successful “sustainable disaster reduction” (Xu et al., 2018).

It is worth acknowledging that, for the past 72 years, the Chinese government has been using different disaster management approaches to mobilize public participation in disaster reduction activities. Since the beginning of group monitoring and prevention endeavors in 1970, the public participation monitoring and warning system (PPMW) has facilitated the establishment of a three-tier monitoring network at the county, township, and village levels to reduce human casualties and management costs (Wu et al., 2020). The community disseminates disaster warning information to residents through instant messaging groups (WeChat groups). In terms of strengthening the construction of “disaster-resistant communities”, China has held a “National Integrated Disaster Reduction Demonstration Community” competition for 11 consecutive years. Community grid-based management is precise to every household and person. The government actively carries out the geohazard-related popularization of science activities to improve the residents' disaster reduction awareness and skills (Yuan et al., 2014).

Although many countries and regions are beginning to recognize the critical role of public participation for sustainable disaster reduction, community residents currently have low levels of participation, poor risk awareness, and a lack of responsibility for disaster prevention and mitigation in the disaster risk management process (Rong and Peng, 2013), which is not conducive to sustainable disaster reduction. Direct or indirect disaster experiences can change individuals' emotions or feelings, which, according to studies of self-protective behavior on an individual or household basis, in turn affect their readiness to take action (Mertens et al., 2018). At the same time, residents in high-risk areas have a clear knowledge and perception of potential hazards and environmental risks, which also cannot be ignored in disaster preparedness research (Khan et al., 2020). Furthermore, it is necessary for people to appreciate the importance of participatory approaches for community catastrophe mitigation and their well-being (Zubir and Amirrol, 2012), as this will facilitate their cooperation with government endeavors. However, few studies consider how to increase public participation in disaster risk management that are still in the early stages of development, and they mostly focus on disasters of a greater impact and concern, such as earthquakes (Hua et al., 2020), droughts (Meadow et al., 2013), and floods (Lawrence et al., 2014; van Heel and van den Born, 2020). Geological hazards such as mudslides and landslides, which have the greatest impact on residents of remote mountainous areas, are under-researched. Therefore, further research is needed to explore the role of the public in geological hazard mitigation management from the perspective of sustainable development, as well as the specific factors and influencing mechanisms that affect public participation.

Public participation is a socio-behavioral decision-making process that is usually studied using social psychological models from such theories as social cognitive theory (Lantz, 1978), the theory of reasoned behavior (Chang, 1998), and the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen, 1991). Of these, the theory of planned behavior (TPB) is widely used to explain the general decision-making process of individual behaviors, such as predicting recycling (Oztekin et al., 2017) and urban smog reduction (Zhu et al., 2020), with high explanatory and predictive power in terms of human behavior (Steinmetz et al., 2016). As the application of TPB progresses, an increasing number of studies have found that adding other variables to enrich the theoretical basis of TPB in different contexts significantly improves explanatory power. Shi et al. (2017) have confirmed that the extended TPB model has strong applicability in the intention of residents to participate in the reduction of PM2.5 emissions. In the study of disaster preparedness behavior, an extended TPB that includes “community participation” and “community-agency trust” can increase the explanatory power of household preparedness in earthquake disasters (Zaremohzzabieh et al., 2021).

Therefore, based on the TPB, we consider risk perception and disaster experience factors from the perspective of risk and disaster reduction behavior and consider the degree of public perception of participation activities from the perspective of participation behavior as three additional explanatory variables. According to the “Standards on National Comprehensive Disaster Reduction Demonstration Communities” and the development of disaster reduction work in China, emergency drills, self-rescue skills, and discussion of emergency plans are selected as the background of disaster reduction management activities with public participation. An empirical study is conducted in Jinchuan County, Sichuan Province, where such geological hazards as flash floods and mudslides are serious issues. The main objectives of this study are as follows: (1) to identify the factors influencing public intention to participate in sustainable disaster mitigation management and ascertain their degree of influence, (2) to extend the application of the TPB in geohazard risk management and test the explanatory and predictive power of the extended TPB model, and (3) to provide recommendations to decision makers for improving public participation. This study has practical implications for mobilizing public participation, improving regional sustainable disaster reduction capacity, and developing a participatory disaster risk reduction management model.

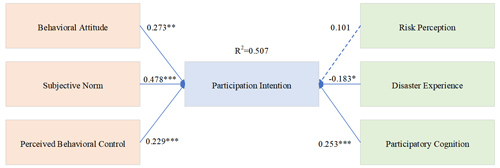

The TPB can be used to explain human behavioral decision processes in specific situations (Ajzen, 1991), such as in health, protective, and learning behaviors. TPB considers behavioral intention to be an important predictor of behavior and is influenced by three independent factors: behavioral attitude (BA), subjective norm (SN), and perceived behavioral control (PBC). The TPB has been successfully applied in public participation behavioral intention studies to air pollution control (Xu et al., 2020), afforestation and carbon reduction (Lin et al., 2012), and community governance (Zhang and Zhang, 2015). However, it has not been fully tested for public participation behavior in disaster management, and only a few studies have explored its applicability in disaster mitigation settings (Ong et al., 2021). A particular issue is that geological hazards, due to the special characteristics of their nurturing environment and disaster-causing factors, differ from such natural disasters as floods and earthquakes in terms of behavioral intention to participate and risk management tools. Therefore, this paper combines the characteristics of geohazards and public participation and adds “risk perception”, “disaster experience”, and “participatory cognition” as additional explanatory variables to the basic TPB model. A theoretical framework of the factors influencing public intention to participate in disaster prevention and mitigation activities was constructed (Fig. 1). The hypothesis based on the model is combined with the reality of comprehensive disaster reduction efforts in China. The communities in the study area have been affected by geohazards, and the local government actively organizes public participation in disaster reduction activities.

2.1 Theory of planned behavior

2.1.1 Behavioral attitude

Behavioral attitude reflects the outcome of an individual's evaluation after

considering the advantages and disadvantages of a particular behavior

(De Jong et al., 2019). Wang and Tsai (2022) found that attitudes positively affected the degree of

teachers' participation in school disaster preparedness. Prior research

shows that attitudes have a positive effect on behavioral intentions. The

more positive the behavioral attitude, the stronger the intention to adopt

the behavior (De Groot and Steg, 2007). In the present study, the

measure of attitude includes the perception of evaluating the advantages and

disadvantages of the behavior, as well as the psychological feelings of the

individual about performing the behavior, prompting hypothesis

H1. Behavioral attitude is positively correlated with the public's participation intentions.

2.1.2 Subjective norm

Subjective norm reflects social pressure from important people or groups

around an individual, which may motivate people to perform or not perform a

certain behavior (Fu et al., 2021; I., 1991). Subjective norm

is measured by the degree to which individuals are surrounded by important

people who approve of their behavioral performance. Past research has shown

that subjective norms are the strongest predictors of intention to seek help

after a natural disaster (Shi and Hall, 2021). Most studies support

the ability of subjective norm to forecast the intention to alleviate

behavior (Slotter et al., 2020) and state that the higher the

individual's perceived subjective norm, the more probable the behavior will

be performed. In this paper, the measurement of subjective norms mainly

includes the influence of surrounding friends, relatives, community

committees, government, and other personnel on individual participation

intention. Thus, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H2. Subjective norm is positively correlated with the public's participation intention.

2.1.3 Perceived behavioral control

Ajzen (1985) has suggested that individual controlling of intention requires

not only internal factors but also external conditions to be considered;

therefore, he added perceived behavioral control to the theory of rational

behavior (TRA) to improve is explanatory power. Perceived behavioral control

refers to an individual's perceived ease of performing a behavior,

reflecting an assessment of its ability and a prediction of the difficulty

of such obstacles as time, money, and distance (Ajzen, 1991). When an

individual perceives that it can easily cope with the impediments, the more

probable it is to perform the behavior (De Leeuw et al., 2015; Gao et

al., 2017). A study of volunteers involved in geological disasters found

that perceived behavioral control had a positive effect on volunteering

(Cahigas et al., 2023). Hence, the measurement of perceived

behavioral control mainly includes the evaluation of one's own ability and

the ability to control the influence of external environment such as time,

money, and distance. The following hypothesis is proposed:

H3. Perceived behavioral control is positively correlated with the public's participation intention.

2.2 Risk perception

Risk perception usually refers to an individual's perception of the

probability of a risky event occurring and its adverse consequences

(Lindell and Hwang, 2008), and fear of risk has also been

suggested as one of the representations of risk perception

(Fischhoff et al., 1978). The impact of “risk perception” on

public behavioral decisions has attracted much attention in past studies,

and research confirms that improving residents' risk perception is key to

community disaster management (Hernández-Moreno and Alcántara-Ayala, 2017). Xu et al. (2019) showed that risk perception and disaster risk

reduction awareness were significantly and positively associated with the

intention to relocate in order to avoid a disaster. Risk perception also

affects how communities respond to disasters and how prepared and motivated

they are to take preventive measures to mitigate the associated risks

(Pagneux et al., 2011).

The results of Miceli's (2008) study suggest that risk

perception can provide reliable psychological indicators of people's actions

and behaviors to reduce their vulnerability during disasters and

environmental emergencies. Therefore, based on the risk perception model

proposed by Slovic (1987), this study measures risk perception

including fear level, consequence severity, probability factor, and control

factor and proposes the following hypothesis:

H4. Risk perception is positively correlated with the public's participation intentions.

2.3 Disaster experience

Residents living in geohazard-prone areas have often had direct or indirect

experiences of disasters, and these experiences could have an impact on

their lives, property, psychology, and livelihoods. Previous studies show

that disaster experiences influence an individual's level of disaster

prevention and behavioral intentions; for example, people who have

experienced floods are more likely to adopt disaster mitigation and

prevention behaviors in the future (Lawrence et al.,

2014), and residents who have experienced disasters have a higher

willingness to invest in safety measures to reduce their personal losses

(Entorf and Jensen, 2020; Seifert et al., 2013). To explain this, some

studies argue that disaster experience is a social learning process, and the

relationship between the environment, behavior, and human thinking and

cognition is an interactive decision (Zhou and Yan, 2019).

Thus, in a severe natural disaster environment, individuals will recognize

the severity of the consequences of a disaster and thus seek more

information and knowledge to counteract its impact on their subsequent lives

since the effects on people of risk events fade over time (Felgentreff,

2003). In the present paper, the assessment of disaster experiences on

behavioral intentions is completed based on the damage to individuals'

lives, health, and property (as well as the impact on their lives and

psychology) from geohazards that occurred in the region in the past decade.

And the following hypothesis is proposed:

H5. Disaster experience is positively correlated with the public's participation intentions.

2.4 Participatory cognition

In studies of environmental management and urban planning, it was found that

public participation can better facilitate the implementation of decisions

and provide opportunities for two-way communication between decision makers

and the public (Fredrik et al., 2012; Gamper and Turcanu, 2009). The

degree of openness to participation and public perceptions of the

participatory process has a significant impact on the level of environmental

participation (Zhang et al., 2018). In

addition, individual behavioral motivation requires consideration of the

degree of attention given to behaviors and events (Echavarren et al., 2019). Past research, through

case studies, has found that behavioral responsibility values and a sense of

belonging increase residents' attention to participatory activities, and

thus their participation intention (Verma et al.,

2019). Therefore, the present paper includes “participatory cognition” to

describe the public's understanding of disaster risk reduction activities

and their concern over participation mechanisms (Huang et al., 2017; Ong

et al., 2021). These mainly include knowledge of participation activities

such as local disaster risk reduction policies and emergency plans, the time

and content of the activities, and the form of participation; the value

and significance of such participation activities as influencing the

democratic power of decision making (Najafi et al., 2017); and

the ongoing significance of public participation (Adams et al., 2017). Thus, the final hypothesis is the following:

H6. Participation cognition is positively correlated with the public's participation intentions.

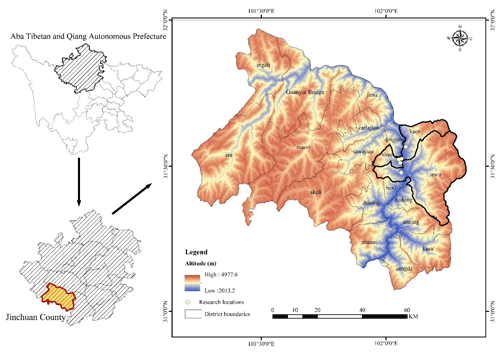

3.1 Study area

Jinchuan County belongs to the Aba Tibetan and Qiang Autonomous Prefecture of Sichuan Province, located on the northwest plateau of Sichuan, at the eastern edge of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau and upper reaches of the Dadu River (Fig. 2). Jinchuan County in 2016 identified a total of 421 geological hazard sites, including 250 mudslides (accounting for 59.38 %), 103 landslides (accounting for 24.47 %), 61 collapses (accounting for 14.49 %), and 7 unstable slopes (accounting for 1.66 %) – threatening the lives of 18 865 people and CNY 931.84 million (Zhang et al., 2016) of property security. On 14 June 2020, Jinchuan County experienced flooding and mudslide disasters, affecting a total of 19 townships, 1899 households, and 7598 people.

To reduce the damage of geological hazards and maintain the safety of people and property, the government of Jinchuan County – located in a geohazard-prone area – has undertaken many disaster prevention and mitigation activities, such as the full-coverage survey work of geological hazard potential sites in Kaer Township and the comprehensive emergency drill for disaster prevention and mitigation in Kasa Township. Jinchuan County's Mulin community was designated a “National Model Disaster Reduction Community” in 2020 and has played an exemplary role in calling for public participation in disaster reduction activities. Being more prominent in terms of public participation in sustainable disaster reduction, Jinchuan County was therefore chosen as the investigation area for this study.

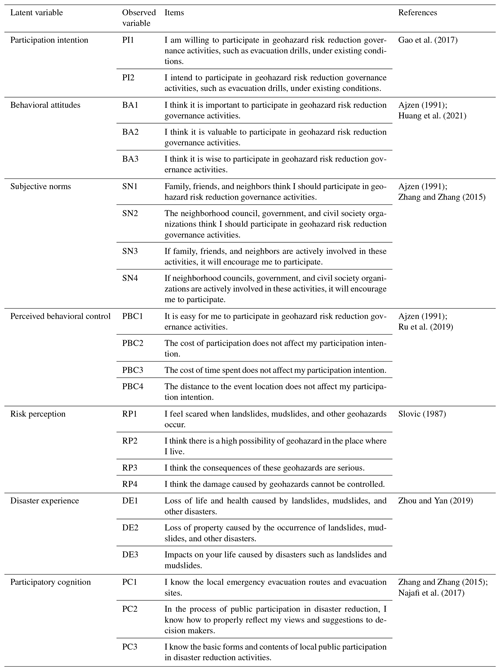

3.2 Measurement tools

The questionnaire comprises three sections. The first introduces the background of the study and public participation in disaster risk reduction governance activities, including emergency drill, self-rescue skills, and discussion of emergency plan preparation. The second involves the basic demographic characteristics, including age and education level. The third is the core of the questionnaire, measuring such latent variables as participation intention, attitude, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, risk perception, disaster experience, and participatory cognition, with variables such as attitude measured with multiple indicators. The measurement items in the questionnaire were adapted and modified to fit the current research context and research topic based on the TPB and research related to public participation. Table 1 shows the related items and their references. Five-point Likert scale was used to measure all potential variables in the questionnaire. Participation intention, behavioral attitudes, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, risk perception, and participatory cognition were measured from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5); disaster experience was measured from very low (1) to very high (5). All the items are positive statements.

3.3 Data collection and analysis

The initial questionnaire prepared was sent to professional scholars, village supporters, and other cadres to pilot it before the main survey. Based on the results, some unclear statements and unreasonable wordings were revised and adjusted. The main survey was conducted in June 2021 in Jinchuan County.

In order to ensure the representativeness and validity of sample data, stratified sampling and random sampling methods are used to determine sample. We invited three experts familiar with the distribution of geological disasters in Jinchuan County and contacted government personnel familiar with local conditions to help us determine the investigation site. According to the disaster situation and public participation in disaster reduction activities, we selected three sample towns: Shaer Township, Kaer Township, and Leiwu Township. Secondly, according to the past disaster situation and the living range of the permanent population, Shaer Township selects the town center, Danzhamu Village, and Shangengzi Village; Kaer Township selects Desheng Village; and Leiwu Town selects Mulin community as the sample village (community). In order to ensure the effective number of samples, a proportional random sampling was conducted according to the total number of permanent residents (26 810) in the three sample villages. One person was randomly selected from each household to fill in a questionnaire. In general, the minimum sample size for SEM is 100–150 (Lomax, 1989), while a reasonable sample size for confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) models is about 150 (Muthén and Muthén, 2002). Therefore, a total of 300 questionnaires were designed and distributed. Residents who could not participate in the survey and residents who did not understand the subject content of the questionnaire were excluded; 260 valid questionnaires (86.7 %) were obtained.

Structural equation modeling (SEM) is a widely used multivariate statistical approach to test theoretical models and hypotheses while estimating modeling path coefficients and measurement errors (Fonseca, 2013). It combines the statistical tools of factor analysis and path analysis to divide variables into potential variables and observed variables. One of the main reasons for researchers to use SEM is that it is the first choice to quantitatively measure whether the theoretical model is correct (Schumacker and Lomax, 2004), which also helps to test the scientificity of social science theories in practical application (Mueller, 1997).

To achieve the research objectives, SEM is used on the survey data to analyze the factors influencing public participation in disaster risk reduction governance intentions included in the extended TPB model. The analysis is in three parts. The first is a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to assess the adequacy and fit of the measurement model (Anderson and Gerbing, 1988), the second is the hypothesis testing and path analysis of the model, and the third uses hierarchical regression to evaluate the predictive power of the basic TPB model and extended TPB model. All calculations are performed by SPSS 23.0 as well as AMOS 23.0.

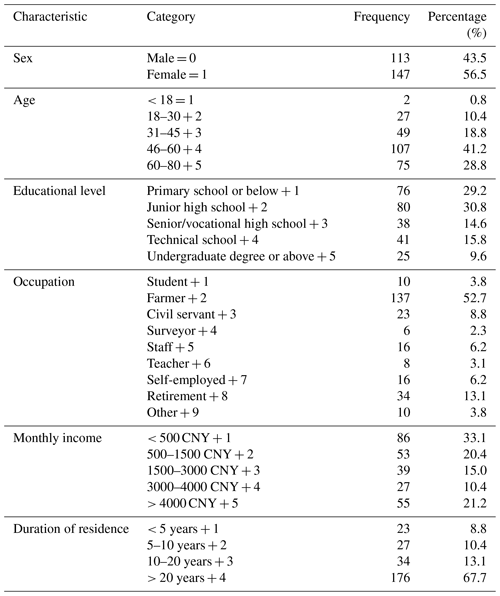

4.1 Demographic characteristics of the sample

Table 2 shows the demographic data of the respondents, with the following distinguishing characteristics: first, the female sample size is slightly larger than the male sample size; in terms of age level, 70 % of the sample is mainly concentrated in the 46 to 60 age group. In terms of educational level, nearly 60 % of the population is below junior high school. About 50 % of the respondents were employed as farmers. Overall, the monthly income of the respondents was generally low, with one-third earning less than CNY 500 per month. The vast majority have been living in the area for more than 10 years. Overall, the range of social groups covered by the respondents and the sample size are consistent with the actual situation and are highly representative.

4.2 Structural reliability and validity

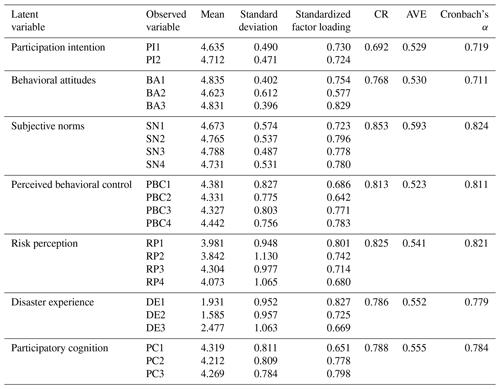

Cronbach's α and composite reliability (Meadow et al., 2013) are used to measure the reliability of each construct in the questionnaire (Huang et al., 2021) (Table 3). The overall Cronbach α coefficient of the questionnaire is 0.786. Cronbach's α coefficients range from 0.711 to 0.824 (generally required to be greater than 0.7). The combined validity (Meadow et al., 2013) values range from 0.692 to 0.853 – generally close to or over 0.7 is considered acceptable (Fornell and Larcker, 1981), indicating that the questionnaire has good internal consistency with Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) = 0.780 (generally required to be greater than 0.6), while Bartlett's test of sphericity = 2100.573, and significance test P < 0.001. These results indicate the data are suitable for factor analysis (Hu et al., 2019). A CFA is used to assess the fit and validity of the constructed model.

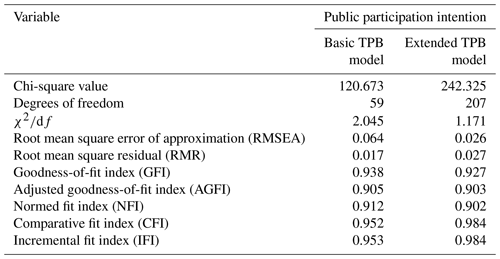

-

Regarding structural validity (Table 4), , root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.026, root mean square residual (RMR) = 0.027, goodness-of-fit index (GFI) = 0.927, adjusted goodness-of-fit index (AGFI) = 0.903, normed fit index (NFI) = 0.902, comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.984, incremental fit index (IFI) = 0.984, indicating a good model fit, as is not greater than 3; RMSEA and RMR are considered good below 0.08; and GFI, AGFI, CFI, NFI, and IFI are greater than 0.9 (Hu and Bentler, 1999).

-

Convergent validity is evaluated by standardized factor loading and average variance extraction (AVE). Table 3 shows that the standardized factor loadings range from 0.577 to 0.829. The AVE values range from 0.523 to 0.593, above the recommended threshold of 0.50 (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). This indicates that each observed variable had some explanatory power for its latent variable, with excellent convergence.

-

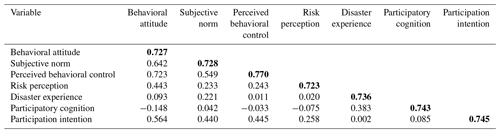

Discriminant validity, using AVE and correlation coefficients, is evaluated. The correlation coefficient between the factors is required to be lower than the square root of the AVE value for discriminant validity to be passed (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). The results show that the correlation coefficients between the latent variables are less than the AVE's square root (Table 5), indicating good discriminant validity.

4.3 Hypothesis test

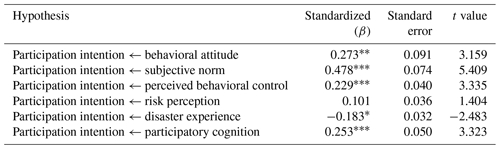

All three hypotheses related to the intention to participate are supported in the basic TPB theoretical model. First, the public's behavioral attitude makes a significant positive contribution to their intention to participate (β=0.273, p < 0.01), and there is a strong correlation between the relationship, indicating that the more valuable members of the public perceive disaster reduction management activities to be to them, the stronger their intention to participate is. In particular, subjective norms have a strong positive effect (β=0.478, p < 0.001), suggesting that social pressure and motivation to participate – or exemplary leadership by close family, friends, and government personnel – would promote individual intention to participate. In addition, perceived behavioral control also has a strong positive relationship (β=0.229, p < 0.001), suggesting that the public's intention to participate is substantially increased when behaviors are perceived to be easier to perform.

Of the new factors added to the extended TPB model, the perception of the participation factor has a positive effect at a significant level of P < 0.001 and contributes to the model to a high degree (β=0.253, P < 0.001), which indicates that the more the public understands the participation process and the form of participation involved, the more positive their participation intention is. Surprisingly, disaster experiences are not consistent with our assumptions about the public's intention to participate (, p < 0.05). This may mean that the less affected the public is by a disaster, the more likely they are to participate in disaster reduction activities. In addition, the hypothesis of risk perception on intention to participate is not supported, and further analysis is needed. Table 6 (Fig. 3) shows the path results of the hypothesis testing.

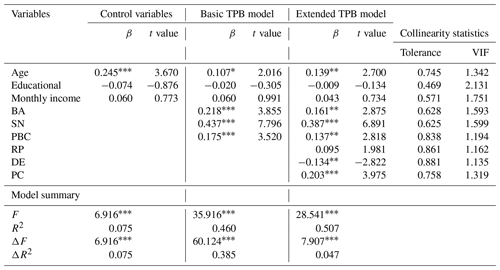

4.4 Multiple hierarchical regression analysis

Multiple hierarchical regression analyses are used to assess the explanatory and predictive power of the basic and extended TPB model (Table 7). Multiple linearity tests are performed on the data by testing the independent variables' linear regression variance inflation factor (VIF) scores, which are calculated to be VIF < 5, indicating the independent variables in the regression model are essentially free of multicollinearity.

Considering previous studies and the actual demographic characteristics of Jinchuan County, the control variables of age, education level, and monthly income are added (Zheng and Wu, 2020). The results show that these three control variables together explain 7.5 % of the variance in participation intention. Then, the basic TPB model explains 46.0 % of the variance – an increase of 38.5 %. In other words, the basic TPB can effectively explain the public's intention to participate in geological hazard mitigation activities. The extended TPB model continues to add three new variables to the original model: risk perception, disaster experience, and participatory perception. Compared with the basic TPB model, it significantly increases the variance of participation intention (R2=0.507) and the explanatory amount by 4.7 %, indicating that the addition of new variables increases the explanatory amount of public participation behavioral intention, and the extended TPB model is more applicable to the prediction of public behavioral intention.

5.1 Factors influencing intention to participate

The present study uses an extended TPB model to explain the participation intention in sustainable disaster reduction. Consistent with previous studies is that individual participation intention is related to attitudes, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, and participatory cognition. Not fully consistent with the previous hypothesis is that H4 does not pass the hypothesis test and the result for H5 is the opposite of the hypothesis.

Of the four predictors that pass the hypothesis test, behavioral attitude has a significant positive effect on the public's intention to participate. Most previous studies conclude that attitude is the main predictor of behavioral intention and that, if individuals have a positive attitude toward a participation matter or issue, they would act corresponding with their attitude (Ajzen and Fishbein, 1977).

The findings indicate that subjective norm is the most important predictor of public participation intention, suggesting that social pressure (encouragement from family and friends, appeals and support from organizations such as the government) is a positive force for the public. In the behavioral decision-making process, people are more likely to be influenced by the perceptions of others and more willing to take advice from those who matter most to them, which reflects a sense of trust in the organization and a sense of social belonging. This is especially the case with smaller communities, which inherently lack internal capacity, and therefore small group participation may be less enthusiastic or even neglected if they continue to lack sustained support from local government (Mathers et al., 2015).

Perceived behavioral control plays a role in having a positive effect on participation intention. Previous studies also confirm that individuals are more likely to participate when they perceive easier execution behaviors and higher self-efficacy (Li et al., 2018; Shi et al., 2017). In other words, people are more willing to participate in activities that are low-cost, less time-consuming, and less difficult to perform.

Participatory cognition is one of the core variables that influence the intention to participate. The higher the level of participatory cognition, the more positive the public's intention to engage in the behavior; from another perspective, participatory activities need to be widely noticed and understood by individuals. Weinstein (2000) found that people with a moderately high level of concern about tornado governance were 56 % to 79 % more likely to take preparedness actions than those with a moderately low level of concern.

Contrary to our hypothesis, however, there is no significant correlation between risk perception and public intention to engage in disaster reduction behaviors – despite such findings having emerged in past studies – although this does not mean that risk perception is not important for individual disaster reduction behaviors (Chen, 2016). First, most residents in the present study are farmers and less educated, which reflects the basic status of rural Sichuan. Members of this group tend to have only a vague perception of disaster risk and generally have a “fluke mentality” compared to that with disasters that have not happened yet. Moreover, structural engineering measures invariably have an immediate protective effect compared to non-engineering measures, with a strong trust in engineering measures reducing the sense of responsibility for disaster reduction. After the Wenchuan earthquake in 2008, for instance, the country paid more attention to the risk management of post-earthquake-derived geological hazards and implemented many structural engineering measures to address clear potential hazard sites (Fig. 4). In the study area, emergency shelter signs were profuse (Fig. 5). In the process of conducting the survey, ad hoc comments were often received indicating the generally high satisfaction of the public with the work of the government, such as in “the government's engineering measures make us feel well protected” and, despite a high perception of surrounding disaster risk, “our houses are safe”. In addition, the image of disaster victims may make them subconsciously believe that they are the target of assistance, which accelerates the transfer of public responsibility for disaster reduction. The participation intention in disaster reduction activities is weak even if they perceive high risks in their environment (Terpstra, 2010).

Figure 4Structural engineering measures to prevent and control: (a) gravity retaining wall, (b) debris flow pre-warning device, (c) discharge chute for debris flow, (d) permeable type of retaining dam for debris flow.

To our surprise, it was found that disaster experience was negatively related to participation intention. This is inconsistent with previous hypotheses, but a similar situation has nevertheless been found in previous studies (Siegrist and Gutscher, 2008). The possible reason for this is the reverse psychological impact of past disaster experiences on disaster victims. On the one hand, disaster victims who have been severely affected by a disaster may show some fear and anxiety about trauma-related situations and activities during the post-disaster trauma phase, and some studies have shown that 20 % of survivors develop psychological disorders that make it difficult to reintegrate into society (Augustijn-Beckers et al., 2010). On the other hand, the loss situation of the subjects of this study was at a moderate level (mean = 1.585–2.477), so they felt more stubborn and lucky than fearful and helpless, believing that “they will not experience the same disaster in the same place twice in their lifetime” (Bustillos Ardaya et al., 2017). Several respondents refused to answer the questionnaire during the research process because of their past tragic experiences. Therefore, it may well be that the impact of disaster experience on the psychological aspects of the public still needs to be taken seriously.

5.2 Implications for participatory disaster risk reduction management

With the government's top-down disaster prevention and mitigation approach, the expected sustainable disaster reduction effect cannot be achieved if the public is not highly motivated to participate (Raikes et al., 2021). In addition, public participation in the disaster prevention and mitigation process can create a down-top surge effect to achieve multiple purposes:

-

People help individuals take responsibility for disaster reduction and achieve a sense of “ownership”: take the initiative to experience risk education, acquire self-rescue skills, and take responsibility for disaster preparedness.

-

People promote mutual communication between the government and the public to build trust: understand the needs and suggestions of the public in promoting geohazard prevention and mitigation activities to develop emergency plans that meet actual local conditions.

-

People express their opinions and needs on an open and transparent platform, monitor government actions, and receive social attention: stakeholders are closely linked to reaching a consensus on disaster reduction to form an “up and down linked” participatory disaster risk management framework.

Future geohazard risk management's focus is to improve public participation enthusiasm based on the existing governance, improve the public participation system, and accelerate the construction of “disaster-resistant communities” to achieve the sustainability goal of minimizing and maximizing disaster mitigation costs and effects, respectively. The findings of the present study provide the following guidance for further strengthening participatory disaster risk management in geohazard-prone areas to achieve sustainable disaster reduction.

First, it is shown that public attitude and participatory perception positively impact on participation intention. If the members of the public feel that the participation process is beneficial and valuable to them, this will significantly increase their intention to participate. Therefore, managers need to provide adequate guidance of the public's perceptions of disaster prevention during the organization and implementation of activities. Policymakers can conduct abundant disaster prevention and mitigation activities to increase the public's awareness of disaster reduction activities, such as joint teams with professional knowledge and social organizations to conduct risk mapping and publicity, knowledge lectures, and the training of self-help and mutual help skills. Studies have confirmed that prior training can help people take appropriate actions in advance and prepare for emergencies (McBride et al., 2019). Encouraging public participation in the design and testing of emergency plans is the most natural and effective form of two-way interactive participation, helping the public to directly understand the functions of local government and the role of members of the public and assisting them in recognizing the social and disaster mitigation responsibilities they need to assume. It can effectively avoid the false sense of security that eventually leads to weak risk awareness due to the transfer of responsibility for disaster preparedness (Wachinger et al., 2013).

Second, according to Chen and Tung (2014), subjective norms can positively influence individuals' behavioral decisions. Social pressure from family, friends, and government workers on individuals may cause them to consider that “everyone around me is taking action, so should I go?” or “everyone thinks I should get involved, so should I try?” before making behavioral decisions. Furthermore, according to traditional Chinese culture, collective interests tend to take priority over individual interests: thus, the government can build on current grid-based management by focusing on the group effect and by adopting incentives (e.g., distributing small gifts) to appeal to residents to participate in disaster reduction activities as a family unit.

Third, emergency management departments and social organizations need to focus on improving the public participation mechanism, optimizing how rural residents obtain information (e.g., exclusive one-to-one services for the elderly and WeChat group notifications for younger groups), and ensuring adequate participation in the participation process. Disseminating basic knowledge concerning geohazard prevention and control to the public and providing a good resource environment for the public is necessary for increasing public awareness and participation. When members of the public understand the participation procedures and associated working arrangements, they can know how to cooperate with the government in the participation process and provide their opinions or suggestions for better feedback.

Fourth, the whole of society should pay attention to the psychological health of the residents and provide timely psychological counseling for affected people. Residents who have experienced disasters are prone to, possibly severe, psychological damage. People recognize severe consequences of disasters from their past disaster experiences, the great loss of life and property, and the sense of difficulty and powerlessness they feel before facing a destructive natural disaster. Therefore, managers need be mindful of providing post-disaster reconstruction help to local disaster victims that is not limited to material help (such as housing and food) but should also provide post-disaster psychological counseling to help disaster victims adequately cope with negative emotional impacts. In implementing future disaster prevention and mitigation policies, it is important that affected people trust, and actively cooperate with, the government. Disaster-affected groups have the most profound understanding of disasters and the local situation, and their experience and local knowledge are valuable for decision makers to improve emergency plans and risk prevention accordingly.

Encouraging public participation as a means of forming a bottom-up complement to the traditional top-down geohazard risk management model provides an important way for improving sustainable disaster reduction. In the present study, risk perception, disaster experience, and participation cognition were added to the basic TPB framework to analyze the factors influencing public intention to participate in disaster reduction in geological hazard-prone areas. A questionnaire survey is used to conduct an empirical analysis in Jinchuan County, one of the most disaster-prone areas in China. The study results show attitude, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, and participation cognition to be significantly and positively correlated with public intention to participate in the extended TPB framework. In contrast, disaster experience is negatively correlated, and risk perception is not significantly correlated with intention to participate. The multilevel regression reveals that the extended TPB model improves the explanatory power of the public's intention to participate in disaster prevention and mitigation compared to the basic model.

Combining the research results and the actual situation in the study area, it is found that the participatory disaster reduction framework contributes to the sustainable development of human society. However, the process requires the joint endeavors of the government, the public, and social groups to reach a “consensus on disaster reduction”. On the one hand, policymakers need to ensure that the public has a good sense of participation and to improve public motivation and disaster prevention capabilities, including diverse forms of activities, rich organizational content, effective publicity, and transparent and convenient participation channels. On the other hand, it is necessary to strengthen the participation mechanism, pay attention to the two-way communication bridge between the public and the government, unite social forces, optimize access to resources, and improve the disaster reduction capacity of individuals and communities to achieve sustainable disaster reduction. This study provides research support for enhancing individual awareness of participation in geohazard prevention and mitigation, improving group awareness of risk prevention, and promoting the overall trend of sustainable disaster reduction in the region. It provides theoretical guidance for mobilizing public and social forces to cooperate with the government to form a participatory disaster management mechanism with upward and downward linkages.

This study has made valuable progress and some noteworthy results, which are crucial for increasing the public's intention to participate in sustainable geohazard mitigation activities. However, this study still faces certain limitations. Firstly, this study analyzed public participation intentions as a whole without considering whether there are cognitive differences and risk awareness differences between townships with different disaster situations and levels of economic development, and the findings are representative of geohazard-prone areas with extensive public participation, such as Jinchuan County in Sichuan, China. Therefore, subsequent studies can delve into the impact of objective environment and risk awareness differences on public participation in disaster prevention and mitigation as a way to obtain valuable findings. In addition, this paper is a combination of factors such as the TPB, risk perception, disaster experience, and participatory cognition on the public's intention to participate, without considering factors such as different power structures, local attachments, and religious beliefs in culture or society. Therefore, future research can go deeper into the influences arising from factors such as cultural perceptions, social relations, and regional emotions, based on understanding the mechanisms influencing the intention to participate.

Analyses were performed in SPSS Statistics Version 23.0 and AMOS Version 23.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). No other type of code or software was used.

The dataset of this study has not been made public due to the protection of the research team's subject and privacy. However, the data are available upon reasonable request by contacting the corresponding author.

HX reviewed and edited the manuscript; TQ analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript draft; YW, SH, and HL performed the investigation; MS and NT proofread the language; HL funding acquisition.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher’s note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. U20A20111 and 72271086), the Sichuan Youth Science and Technology Innovation Research Team Project (grant no. 2020JDTD0006), Innovation and Entrepreneurship Talents Program in Jiangsu Province, 2021 (project no. JSSCRC2021507, fund no. 2016/B2007224), the “13th Five-Year” Plan of Philosophy and Social Sciences of Guangdong Province (2019 General Project) (grant no. GD19CGL27), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (grant no. B210201014).

This research has been supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. U20A20111 and 72271086), the Sichuan Youth Science and Technology Innovation Research Team Project (grant no. 2020JDTD0006), Innovation and Entrepreneurship Talents Program in Jiangsu Province, 2021 (project no. JSSCRC2021507, fund no. 2016/B2007224), the “13th Five-Year” Plan of Philosophy and Social Sciences of Guangdong Province (2019 General Project) (grant no. GD19CGL27), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (grant no. B210201014).

This paper was edited by Animesh Gain and reviewed by Md. Shibly Sadik and one anonymous referee.

Adams, R. M., Rivard, H., and Eisenman, D. P.: Who Participates in Building Disaster Resilient Communities:A Cluster-Analytic Approach, J. Public Health Man., 23, 37–46, https://doi.org/10.1097/PHH.0000000000000387, 2017.

Ajzen, I.: From Intentions to Actions: A Theory of Planned Behavior, edited by: Kuhl, J. and Beckmann, J., Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 11–39, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-69746-3_2, 1985.

Ajzen, I. and Fishbein, M.: Attitude-behavior relations: A theoretical analysis and review of empirical research, Psychol. Bull., 84, 888–918, https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.84.5.888, 1977.

Ajzen, I.: The theory of planned behavior, Organ. Behav. Hum. Dec., 50, 179–211, https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T, 1991.

Anderson, J. C. and Gerbing, D. W.: Structural Equation Modeling in Practice: A Review and Recommended Two-Step Approach, Psychol. Bull., 103, 411–423, https://doi.org/10.1037//0033-2909.103.3.411, 1988.

Augustijn-Beckers, E. W., Flacke, J., and Retsios, B.: Investigating the effect of different pre-evacuation behavior and exit choice strategies using agent-based modeling, Procedia Engineer., 3, 23–35, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2010.07.005, 2010.

Bustillos Ardaya, A., Evers, M., and Ribbe, L.: What influences disaster risk perception? Intervention measures, flood and landslide risk perception of the population living in flood risk areas in Rio de Janeiro state, Brazil, Int. J. Disast. Risk Re., 25, 227–237, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2017.09.006, 2017.

Cahigas, M. M. L., Prasetyo, Y. T., Persada, S. F., and Nadlifatin, R.: Filipinos' intention to participate in 2022 leyte landslide response volunteer opportunities: The role of understanding the 2022 leyte landslide, social capital, altruistic concern, and theory of planned behavior, Int. J. Disast. Risk Re., 84, 103485, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2022.103485, 2023.

Chang, M. K.: Predicting Unethical Behavior: A Comparison of the Theory of Reasoned Action and the Theory of Planned Behavioressment, J. Bus. Ethics, 17, 1825–1834, https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005721401993, 1998.

Chen, M. F.: Extending the theory of planned behavior model to explain people's energy savings and carbon reduction behavioral intentions to mitigate climate change in Taiwan–moral obligation matters, J. Clean. Prod., 112, 1746–1753, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.07.043, 2016.

Chen, M. F. and Tung, P. J.: Developing an extended Theory of Planned Behavior model to predict consumers' intention to visit green hotels, Int. J. Hosp. Manag., 36, 221–230, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2013.09.006, 2014.

Cwa, B. and Sjc, D.: Meeting at the crossroads? Developing national strategies for disaster risk reduction and resilience: Relevance, scope for, and challenges to, integration, Int. J. Disast. Risk Re., 45, 101452, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2019.101452, 2020.

De Groot, J. and Steg, L.: General beliefs and the theory of planned behavior: The role of environmental concerns in the TPB, J. Applied Soc. Psychol., 37, 1817–1836, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2007.00239.x, 2007.

De Jong, M. D. T., Neulen, S., and Jansma, S. R.: Citizens' intentions to participate in governmental co-creation initiatives: Comparing three co-creation configurations, Gov. Inform. Q., 36, 490–500, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2019.04.003, 2019.

De Leeuw, A., Valois, P., Ajzen, I., and Schmidt, P.: Using the theory of planned behavior to identify key beliefs underlying pro-environmental behavior in high-school students: Implications for educational interventions, J. Environ. Psychol., 42, 128–138, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2015.03.005, 2015.

Dube, E.: The build-back-better concept as a disaster risk reduction strategy for positive reconstruction and sustainable development in Zimbabwe: A literature study, Int. J. Disast. Risk Re., 43, 101401, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2019.101401, 2020.

Echavarren, J. M., Balžekienė, A., and Telešienė, A.: Multilevel analysis of climate change risk perception in Europe: Natural hazards, political contexts and mediating individual effects, Safety Sci., 120, 813–823, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2019.08.024, 2019.

Entorf, H. and Jensen, A.: Willingness-to-pay for hazard safety – A case study on the valuation of flood risk reduction in Germany, Safety Sci., 128, 104657, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2020.104657, 2020.

Felgentreff, C.: Post-Disaster Situations as “Windows of Opportunity”? Post-Flood Perceptions and Changes in the German Odra River Region after the 1997 Flood, Erde, 134, 163–180, 2003.

Fischhoff, B., Slovic, P., Lichtenstein, S., Read, S., and Combs, B.: How safe is safe enough? A psychometric study of attitudes towards technological risks and benefits, Policy Sci., 9, 127–152, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00143739, 1978.

Fonseca, M.: Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, Third Edition by Rex B. Kline, Int. Stat. Rev., 81, 172–173, https://doi.org/10.1111/insr.12011_25, 2013.

Fornell, C. and Larcker, D. F.: Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error, J. Marketing Res., 18, 39–50, https://doi.org/10.2307/3151312, 1981.

Fredrik, K., Jesper, H., Eva, S., and Karin, H.: Exploring user participation approaches in public e-service development, Gov. Inf. Q., 29, 158–168, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2011.07.009, 2012.

Fu, M. Q., Liu, R., and Zhang, Y.: Why do people make risky decisions during a fire evacuation? Study on the effect of smoke level, individual risk preference, and neighbor behavior, Safety Sci., 140, 105245, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2021.105245, 2021.

Gamper, C. D. and Turcanu, C.: Can public participation help managing risks from natural hazards?, Safety Sci., 47, 522–528, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2008.07.005, 2009.

Gao, L., Wang, S. Y., Li, J., and Li, H. D.: Application of the extended theory of planned behavior to understand individual's energy saving behavior in workplaces, Resour. Conserv. Recy., 127, 107–113, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2017.08.030, 2017.

Gong, K., Xu, H. L., Liu, X. L., Chen, M., Yang, C. C., and Yang, Y.: Risk Perception of Mountain Hazards and Assessment of Emergency Management of Western Communities in China – A Case Study of Xiaoyudong Town in Pengzhou City, Sichuan Province, Bulletin of Soil and Water Conservation, 38, 183–188, https://doi.org/10.13961/j.cnki.stbctb.2018.02.030, 2018.

Hernández-Moreno, G. and Alcántara-Ayala, I.: Landslide risk perception in Mexico: a research gate into public awareness and knowledge, Landslides, 14, 351–371, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10346-016-0683-9, 2017.

Hu, H., Zhang, J. H., Wang, C., Yu, P., and Chu, G.: What influences tourists' intention to participate in the Zero Litter Initiative in mountainous tourism areas: A case study of Huangshan National Park, China, Sci. Total Environ., 657, 1127–1137, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.12.114, 2019.

Hu, L. T. and Bentler, P. M.: Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives, Struct. Equ. Modeling, 6, 1–55, https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118, 1999.

Hua, C. L., Huang, S. K., Lindell, M. K., and Yu, C. H: Rural households' perceptions and behavior expectations in response to seismic hazard in Sichuan, China, Safety Sci., 125, 104622, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2020.104622, 2020.

Huang, H., Hou, K., Qiu, D. Q., Li, N., and Zhao, Z. J.: A Cognitive Study on Public Participation in Environmental Impact Assessment of Beijing Residents, Acta Scientiarum Naturalium Universitatis Pekinensis, 53, 462–468, https://doi.org/10.13209/j.0479-8023.2017.023, 2017.

Huang, Y., Francisco, A., Yang, J., Qin, Y. T., and Wen, Y. L.: Predicting citizens' participatory behavior in urban green space governance: Application of the extended theory of planned behavior, Urban For. Urban Green., 61, 127110, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2021.127110, 2021.

Khan, G., Qureshi, J. A., Khan, A., Shah, A., Ali, S., Bano, I., and Alam, M.: The role of sense of place, risk perception, and level of disaster preparedness in disaster vulnerable mountainous areas of Gilgit-Baltistan, Pakistan, Environ. Sci. Pollut. R., 27, 44342–44354, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-020-10233-0, 2020.

Lantz, J. E.: Cognitive theory and social casework, Soc. Work, 23, 361–366, https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/23.5.361, 1978.

Lawrence, J., Quade, D., and Becker, J.: Integrating the effects of flood experience on risk perception with responses to changing climate risk, Nat. Hazards, 74, 1773–1794, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-014-1288-z, 2014.

Li, J. R., Zuo, J., Cai, H., and Zillante, G.: Construction waste reduction behavior of contractor employees: An extended theory of planned behavior model approach, J. Clean. Prod., 172, 1399–1408, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.10.138, 2018.

Lin, J. C., Wu, C. S., Liu, W. Y., and Lee, C. C.: Behavioral intentions toward afforestation and carbon reduction by the Taiwanese public, Forest Policy Econ., 14, 119–126, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2011.07.016, 2012.

Lindell, M. K. and Hwang, S. N.: Households' perceived personal risk and responses in a multihazard environment, Risk Anal., 28, 539–556, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.2008.01032.x, 2008.

Lomax, R. G.: Covariance structure analysis: Extensions and developments, 1, JAI Press, 171–204, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/279528915_Covariance_structure_analysis_Extensions_and_developments (last access: 10 April 2023), 1989.

Mathers, A., Dempsey, N., and Molin, J. F.: Place-keeping in action: Evaluating the capacity of green space partnerships in England, Landscape Urban Plan., 139, 126–136, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2015.03.004, 2015.

McBride, S. K., Becker, J. S., and Johnston, D. M.: Exploring the barriers for people taking protective actions during the 2012 and 2015 New Zealand ShakeOut drills, Int. J. Disast. Risk Re., 37, 101150, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2019.101150, 2019.

Meadow, A. M., Crimmins, M. A., and Ferguson, D. B.: FIELD OF DREAMS OR DREAM TEAM? Assessing Two Models for Drought Impact Reporting in the Semiarid Southwest, B. Am. Meteorol. Soc., 94, 1507–1517, https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-11-00168.1, 2013.

Mertens, K., Jacobs, L., Maes, J., Poesen, J., Kervyn, M., and Vranken, L.: Disaster risk reduction among households exposed to landslide hazard: A crucial role for self-efficacy?, Land Use Policy, 75, 77–91, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.01.028, 2018.

Miceli, R., Sotgiu, I., and Settanni, M. Disaster preparedness and perception of flood risk: A study in an alpine valley in Italy, J. Environ. Psychol., 28, 164–173, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2007.10.006, 2008.

Mueller, R. O.: Structural equation modeling: Back to basics, Struct. Eq. Model., 4, 353–369, https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519709540081, 1997.

Muthén, L. K. and Muthén, B. O.: How to Use a Monte Carlo Study to Decide on Sample Size and Determine Power, Struct. Equ. Model, 9, 599–620, https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328007sem0904_8, 2002.

Najafi, M., Ardalan, A., Akbarisari, A., Noorbala, A. A., and Elmi, H.: Salient Public Beliefs Underlying Disaster Preparedness Behaviors: A Theory-Based Qualitative Study, Prehospital and Disaster Medicine, 32, 124–133, https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049023X16001448, 2017.

Olawumi, T. O. and Chan, D. W. M.: A scientometric review of global research on sustainability and sustainable development, J. Clean. Prod., 183, 231–250, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.02.162, 2018.

Ong, A. K. S., Prasetyo, Y. T., Lagura, F. C., Ramos, R. N., Sigua, K. M., Villas, J. A., Young, M. N., Diaz, J. F. T., Persada, S. F., and Redi, A. A. N. P.: Factors affecting intention to prepare for mitigation of “the big one” earthquake in the Philippines: Integrating protection motivation theory and extended theory of planned behavior, Int. J. Disast. Risk Re., 63, 102467, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2021.102467, 2021.

Oztekin, C., Teksöz, G., Pamuk, S., Sahin, E., and Kilic, D. S.: Gender perspective on the factors predicting recycling behavior: Implications from the theory of planned behavior, Waste Manage., 62, 290–302, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2016.12.036, 2017.

Pagneux, E., Gísladóttir, G., and Jónsdóttir, S.: Public perception of flood hazard and flood risk in Iceland: a case study in a watershed prone to ice-jam floods, Nat. Hazards, 58, 269–287, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-010-9665-8, 2011.

Pearce, L.: Disaster management and community planning, and public participation: How to achieve sustainable hazard mitigation, Nat. Hazards, 28, 211–228, https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022917721797, 2003.

Peters, K., and Peters, L. E. R.: Terra incognita: the contribution of disaster risk reduction in unpacking the sustainability–peace nexus, Sustain. Sci., 16, 1173–1184, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-021-00944-9, 2021.

Raikes, J., Smith, T. F., Baldwin, C., and Henstra, D.: Linking disaster risk reduction and human development, Climate Risk Management, 32, 100291, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crm.2021.100291, 2021.

Rong, C. and Peng, C.: Current Situation and Prospect of Community-based Disaster Risk Management, Journal of Catastrophology, 28, 133–138, https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1000-811X.2013.01.028, 2013.

Roopnarine, R., Eudoxie, G., Wuddivira, M. N., Saunders, S., Lewis, S., Spencer, R., Jeffers, C., Bobb, T. H., and Roberts, C.: Capacity building in participatory approaches for hydro-climatic Disaster Risk Management in the Caribbean, Int. J. Disast. Risk Re., 66, 102592, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2021.102592, 2021.

Ru, X. J., Qin, H. B., and Wang, S. Y.: Young people's behaviour intentions towards reducing PM2.5 in China: Extending the theory of planned behaviour, Resour. Conserv. Recy., 141, 99–108, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2018.10.019, 2019.

Schumacker, R. E. and Lomax, R. G.: A Beginner's Guide to Structural Equation Modeling, Technometrics, 47, 522–522, https://doi.org/10.1198/tech.2005.s328, 2004.

Seidler, R., Dietrich, K., Schweizer, S., Bawa, K. S., and Khaling, S.: Progress on integrating Climate Change Adaptation and Disaster Risk Reduction for sustainable development pathways in South Asia: evidence from six research projects, Int. J. Disast. Risk Re., 31, 92–101, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2018.04.023, 2018.

Seifert, I., Botzen, W. J. W., Kreibich, H., and Aerts, J. C. J. H.: Influence of flood risk characteristics on flood insurance demand: a comparison between Germany and the Netherlands, Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci., 13, 1691–1705, https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-13-1691-2013, 2013.

Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030: Australian Journal of Emergency Management, 30, 9–10, https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/informit.364874973593803 (last access: 10 April 2023), 2015

Shi, H. X., Fan, J., Zhao, D. T: Predicting household PM2.5-reduction behavior in Chinese urban areas: An integrative model of Theory of Planned Behavior and Norm Activation Theory, J. Clean. Prod., 145, 64–73, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.12.169, 2017.

Shi, H. X., Wang, S. Y., and Zhao, D. T.: Exploring urban resident's vehicular PM2.5 reduction behavior intention: An application of the extended theory of planned behavior, J. Clean. Prod., 147, 603–613, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.01.108, 2017.

Shi, S. and Hall, B. J.: Help-seeking intention among Chinese college students exposed to a natural disaster: an application of an extended theory of planned behavior (E-TPB), Soc. Psych. Psych. Epid., 56, 1273–1282, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-020-01993-8, 2021.

Siegrist, M. and Gutscher, H.: Natural hazards and motivation for mitigation behavior: People cannot predict the affect evoked by a severe flood, Risk Anal., 28, 771–778, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.2008.01049.x, 2008.

Slotter, R., Trainor, J., Davidson, R., Kruse, J., and Nozick, L.: Homeowner mitigation decision-making: Exploring the theory of planned behaviour approach, J. Flood Risk Manag., 13, e12667, https://doi.org/10.1111/jfr3.12667, 2020.

Slovic, P.: Perception of risk, Science, 236, 280–285, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.3563507, 1987.

Steinmetz, H., Knappstein, M., Ajzen, I., Schmidt, P., and Kabst, R.: How Effective are Behavior Change Interventions Based on the Theory of Planned Behavior? A Three-Level Meta-Analysis, Zeitschrift fur Psychologie-Journal of Psychoology, 224, 216–233, https://doi.org/10.1027/2151-2604/a000255, 2016.

Stephan, C., Norf, C., and Fekete, A.: How “Sustainable” are Post-disaster Measures? Lessons to Be Learned a Decade After the 2004 Tsunami in the Indian Ocean, Int. J. Disast. Risk Sc., 8, 33–45, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13753-017-0113-1, 2017.

Terpstra, T.: Flood preparedness: thoughts, feelings and intentions of the Dutch public, PhD Thesis, Research UT, graduation UT, University of Twente, [University of Twente], 163 pp., https://doi.org/10.3990/1.9789036529549, 2010.

van Heel, B. F. and van den Born, R. J. G.: Studying residents' flood risk perceptions and sense of place to inform public participation in a Dutch river restoration project, J. Integr. Environ. Sci., 17, 35–55, https://doi.org/10.1080/1943815X.2020.1799826, 2020.

Verma, V. K., Chandra, B., and Kumar, S.: Values and ascribed responsibility to predict consumers' attitude and concern towards green hotel visit intention, J. Bus. Res., 96, 206–216, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.11.021, 2019.

Wachinger, G., Renn, O., Begg, C., and Kuhlicke, C.: The Risk Perception Paradox – Implications for Governance and Communication of Natural Hazards, Risk Anal., 33, 1049–1065, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.2012.01942.x, 2013.

Wang, J. J., and Tsai, N. Y.: Factors affecting elementary and junior high school teachers' behavioral intentions to school disaster preparedness based on the theory of planned behavior, Int. J. Disast. Risk Re., 69, 102757, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2021.102757, 2022.

Weinstein, N. D., Lyon, J. E., Rothman, A. J., and Cuite, C. L.: Preoccupation and affect as predictors of protective action following natural disaster, Brit. J. Health Psych., 5, 351–363, https://doi.org/10.1348/135910700168973, 2000.

Wu, S. N., Yu, L., Cui, P., Chen, R., and Yin, P.: Chinese public participation monitoring and warning system for geological hazards, J. Mt. Sci., 17, 1553–1564, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11629-019-5933-6, 2020.

Xu, D., Hazeltine, B., Xu, J. P., and Prasad, A.: Public participation in NGO-oriented communities for disaster prevention and mitigation (N-CDPM) in the Longmen Shan fault area during the Wenchuan and Lushan earthquake periods, Environ. Hazards, 17, 371–395, https://doi.org/10.1080/17477891.2018.1491382, 2018.

Xu, D. D., Liu, Y., Deng, X., Qing, C., Zhuang, L. M., Yong, Z. L., and Huang, K.: Earthquake Disaster Risk Perception Process Model for Rural Households: A Pilot Study from Southwestern China, Int. J. Environ. Res. Pu., 16, 4512, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16224512, 2019.

Xu, Z. H., Shan, J. Z., Li, J. M., and Zhang, W. S.: Extending the theory of planned behavior to predict public participation behavior in air pollution control: Beijing, China, J. Environ. Plann. Man., 63, 669–688, https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2019.1603821, 2020.

Yuan, L., Zeng, X. R., Chu, X. J., Li, Q., and Gong, K. H.: Countermeasure Innovation of the Popular Science Advocacy in the Protection Against and Mitigation Disasters, Journal of Catastrophology, 29, 174–178, 2014.

Zaremohzzabieh, Z., Samah, A. A., Roslan, S., Shaffril, H. A. M., D'Silva, J. L., Kamarudin, S., and Ahrari, S.: Household preparedness for future earthquake disaster risk using an extended theory of planned behavior, Int. J. Disast. Risk Re., 65, 102533, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2021.102533, 2021.

Zhang, H. and Zhang, Z. S.: Analysis of Influencing Factors of Resident Participation in Community Governance Based on Theory of Planned Behavior – A Case Study of Tianjin, Journal of Tianjin University (Social Sciences), 17, 523–528, 2015.

Zhang, J. Y., Pan, J. L., Fan, B., Li, W. Z., Yin, J. J., Gao, J. H., Li, G. Y., Wang, B. Q., and Chen, Y.: Report on Detailed Investigation Results of Geological Hazards in Jinchuan County, Aba Prefecture, Sichuan Province, https://www.ngac.cn/dzzlfw_sjgl/d2d/dse/category/detail.do?method=cdetail&_id=102_149176&tableCode=ty_qgg_edmk_t_ajxx&categoryCode=dzzlk (last access: 24 April 2023), 2016.

Zhang, X. J., Jennings, E. T., and Zhao, K.: Determinants of environmental public participation in China: an aggregate level study based on political opportunity theory and post-materialist values theory, Pol. Stud., 39, 498–514, https://doi.org/10.1080/01442872.2018.1481502, 2018.

Zheng, Y. and Wu, G. C.: Analysis of Factors Affecting the Chinese Public Earthquake Emergency Preparedness, Technology for Earthquake Disaster Prevention, 15, 591–600, https://doi.org/10.11899/zzfy20200313, 2020.

Zhou, C. X. and Yan, F. X.: Study on the Willingness of Farmers to Participate in Disaster Reduction Public Goods Supply:Multiple Mediating Role of Risk Perception and Self-efficacy, Journal of Southwest University for Nationalities, 40, 64–71, https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1004-3926.2019.08.010, 2019.

Zhu, W. W., Yao, N. Z., Guo, Q. Z., and Wang, F. B.: Public risk perception and willingness to mitigate climate change: city smog as an example, Environ. Geochem. Hlth., 42, 881–893, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10653-019-00355-x, 2020.

Zubir, S. S. and Amirrol, H.: Disaster risk reduction through community participation, Sustainable Development and Ecological Hazards III, 148, 195–206, https://doi.org/10.2495/RAV110191, 2012.