the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Structural weakening of the Merapi dome identified by drone photogrammetry after the 2010 eruption

Herlan Darmawan

Thomas R. Walter

Valentin R. Troll

Agus Budi-Santoso

Lava domes are subjected to structural weakening that can lead to gravitational collapse and produce pyroclastic flows that may travel up to several kilometers from a volcano's summit. At Merapi volcano, Indonesia, pyroclastic flows are a major hazard, frequently causing high numbers of casualties. After the Volcanic Explosivity Index 4 eruption in 2010, a new lava dome developed on Merapi volcano and was structurally destabilized by six steam-driven explosions between 2012 and 2014. Previous studies revealed that the explosions produced elongated open fissures and a delineated block in the southern dome sector. Here, we investigated the geomorphology, structures, thermal fingerprint, alteration mapping and hazard potential of the Merapi lava dome by using drone-based geomorphologic data and forward-looking thermal infrared images. The block on the southern dome of Merapi is delineated by a horseshoe-shaped structure with a maximum depth of 8 m and it is located on the unbuttressed southern steep flank. We identify intense thermal, fumarole and hydrothermal alteration activities along this horseshoe-shaped structure. We conjecture that hydrothermal alteration may weaken the horseshoe-shaped structure, which then may develop into a failure plane that can lead to gravitational collapse. To test this instability hypothesis, we calculated the factor of safety and ran a numerical model of block-and-ash flow using Titan2D. Results of the factor of safety analysis confirm that intense rainfall events may reduce the internal friction and thus gradually destabilize the dome. The titan2D model suggests that a hypothetical gravitational collapse of the delineated unstable dome sector may travel southward for up to 4 km. This study highlights the relevance of gradual structural weakening of lava domes, which can influence the development fumaroles and hydrothermal alteration activities of cooling lava domes for years after initial emplacement.

- Article

(17861 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(120 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Lava domes are viscous lava extrusions that accumulate at volcanic vents and experience exogenous and endogenous growth (Hale, 2008). During formation of lava domes, they may start lateral flow as coulees, be subject to cooling and subsidence and can develop concentric fractures on the flat-topped summit of the dome (Walter et al., 2013b; Salzer et al., 2017; Rhodes et al., 2018). Many details of the development, geometric organization and actual formation processes of dome structures remain poorly understood. External factors such as intense rainfall, hydrothermal alteration, gas overpressure, mechanical weakening and earthquakes may further augment instability and promote a dome collapse (Voight and Elsworth, 2000; Reid et al., 2001; Ball et al., 2015). Once fracture arrangements are established in a lava dome, volcanic gas and rainwater are able to flow that may cause hydrothermal alteration and gas overpressure along the structure, which may lead to dome destruction even during quiescent periods (Voight and Elsworth, 2000; Reid et al., 2001; Elsworth et al., 2004; Simmons et al., 2004; Taron et al., 2007; Ball et al., 2015). Structural weakening and thus instability of a lava dome due to these processes may then cause hazardous rock falls or block-and-ash flows (Calder et al., 2015).

The dome collapse at Soufrière Hills Volcano (SHV), Montserrat in 1998–1999, is an example of rain-triggered collapse that followed a period of quiescence. The SHV dome collapse produced pyroclastic density currents (PDC) with a volume of 22×106 m3 that traveled up to ∼3 km from the summit (Norton et al., 2002; Elsworth et al., 2004). The rainwater infiltrated through identified fractures, produced gas overpressure within the lava dome carapace, and then triggered dome collapses that were characterized by hydrothermal alteration and structural instability (Voight, 2000; Elsworth et al., 2004). This event demonstrates that identifying a structural weakening is crucial for volcanic hazard mitigation.

However, identifying the potential hazard of lava domes is often difficult and requires high-quality observational datasets complemented by modeling analyses (Voight, 2000). Dome building volcanoes are often steep sided hazardous edifices, where direct access is very limited and acquisition of high-quality field data is challenging. In contrast, remote sensing techniques, such as satellite imageries, aerial photogrammetric and thermal imaging can provide detailed information on the structure, deformation, geomorphology and thermal signature of active lava domes (James and Varley, 2012; Walter et al., 2013a; Salzer et al., 2014; Thiele et al., 2017; Darmawan et al., 2018), which allows the study of important parameters for assessment of dome instability and potential hazards (Voight and Elsworth, 2000; Elsworth et al., 2004; Simmons et al., 2004; Taron et al., 2007). In this respect, the degree of instability of lava domes can be assessed by using a factor of safety equation (Voight and Elsworth, 2000; Simmons et al., 2004; Taron et al., 2007). Factor of safety (FS) is widely used to calculate slope stability (Bishop, 1955) and it is calculated by dividing resisting forces to driving forces that act on a failure plane (α; Voight, 2000). A result of FS ≤1 indicates a failure condition. However, in a lava dome some additional forces may act on a failure plane due to, e.g., degassing and rainfall activities (Simmons et al., 2004). Here, we test the first factor of safety model at the Merapi lava dome to assess its stability under rainfall conditions.

In a case of structural dome instability, the hazard arising from dome collapses can be simulated by geophysical mass flow software, such as Titan2D (Patra et al., 2005; Sheridan et al., 2005). Titan2D is a software to model 2-D geophysical mass flow based on a depth averaged model for an incompressible continuum granular flow and was validated through laboratory experiments (Patra et al., 2005). It is publicly available and has been used to map dynamics and distribution of block-and-ash flows at Merapi during the 2006 and 2010 eruptions (Charbonnier and Gertisser, 2009, 2012; Charbonnier et al., 2013).

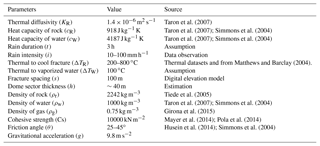

Figure 1(a) Shaded relief of DEM from Gerstenecker et al. (2005) shows the morphology of Merapi volcano, the most active volcano in Indonesia. Merapi is located ∼30 km from the densely populated city of Yogyakarta and therefore the activity of Merapi is intensively monitored by five observatories (blue dots). (b) TLS and drone photogrammetry field campaigns have been conducted in September 2014 and October 2015, respectively, to investigate the detailed structure and morphology of the Merapi lava dome. Coordinates are in Universal Transverse Mercator (UTM) meters. (c) The aerial image of the Merapi dome in 2014 shows the delineated unstable dome sector on the southern flank that is the focus of the present investigation.

In this study, we employed drone photogrammetry and terrestrial laser scanning (TLS), thermal mapping, factor of safety calculation and Titan2D simulation to assess structural instability and hazards potential of the current Merapi lava dome. Combination of TLS and drone photogrammetry is able to generate a high-resolution digital elevation model (DEM) of the Merapi summit, which compares favorably to the satellite-based DEM. For the first time, we are now able to generate a realistic model of the morphology and structure at the Merapi summit. Thermal mapping by using a forward-looking infrared (FLIR) camera also provides detailed locations of hydrothermal fluid activity. The information of geomorphology, structure and thermal activity allows us to analyze the factor of safety, and to set up a forward simulation of the Titan2D model. The combined results help to better understand the relevance of dome fracturing, structural weakening and to outline the potential hazard zone affected in case of a dome sector collapse.

1.1 Merapi volcano

Merapi volcano is a basaltic to andesitic volcano that formed due to subduction of the Indo-Australian oceanic plate beneath the Eurasian continental plate (Hamilton, 1979). Merapi volcano is one of the most active and dangerous volcanoes in Indonesia, with more than 1 million people living on the volcano's flanks. Moreover, the city of Yogyakarta with 3 million inhabitants is located only ∼30 km from the volcano's summit (Fig. 1; Lavigne et al., 2015). The volcanic activity of Merapi has been well documented since the 1800s and its typical eruption style is dome extrusion and block-and-ash flows (Voight et al., 2000). The extrusion rate of a lava dome at Merapi may strongly vary, ranging from ∼0.04 m3 s−1 (Siswowidjoyo et al., 1995), up to 35 m3 s−1 or more during, e.g., the 2010 volcanic crisis (Pallister et al., 2013).

Merapi shows signs of interactions with surrounding environmental influences, and for instance rainfall appears to correlate with fumarole activity and seismic intensity (Richter et al., 2004), and tectonic earthquakes can influence eruptive activity (Walter et al., 2007, 2015; Carr et al., 2018). The volcano erupted several times during the last few decades, once every 3–5 years on average, with the largest explosive event recorded in 2010. The 2010 eruption removed parts of the summit area (Surono et al., 2012), excavated a ∼200 m deep crater and was followed by re-growth of a new dome (Kubanek et al., 2015). The new lava dome was intermittently destroyed by several explosive events again between 2012 and 2014, which also caused elongated open fissures (Fig. 1b, c; Walter et al., 2015), and a horseshoe-shaped structure that highly altered and delineated the southern part of the dome (Fig. 1c; Darmawan et al., 2018). The horseshoe-shaped structure is posing a safety risk due to weakening from hydrothermal alteration and may possibly collapse in the foreseeable future.

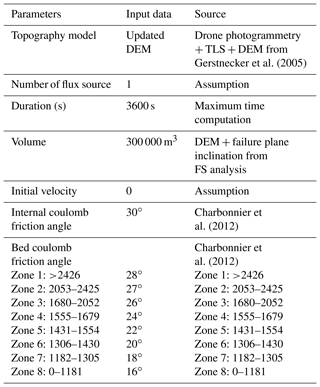

Figure 2(a) Slope map of the Merapi summit shows that the Merapi flanks are steep, especially the crater which has a slope of ∼80∘. (b) Photomosaic of drone aerial images shows that the summit is highly fractured with 150∘ from N to E and highly altered. (c) Rock alteration occurs at the crater wall, the fissure at the dome, and the southern sector of the dome. A cross section of lines (d) r-s and (e) p-q show that the crater has a maximum depth of 146 m at the northeast area. The current Merapi dome is located in the middle of the deep crater and shows a possible unstable sector as sketched in (e).

2.1 Observational data

We conducted TLS, drone photogrammetry and thermal infrared field campaigns to investigate geomorphology, structure, hydrothermal alteration and thermal distribution of the Merapi lava dome. The TLS data was acquired on 18 September 2014 by using a Riegl 6000 instrument from the eastern rim of the summit crater (7∘32′25.0161 S, 110∘26′51.2110 E), looking down westward onto the dome. The TLS instrument was set by using a pulse repetition rate (PRR) of 30 kHz, an observation range of 0.129–4393.75 m, a theta range (vertical) of 73–120∘, a sampling angle of 0.041∘ and a phi range (horizontal) of 33–233∘ with a sampling angle of 0.05∘. We used 12 local reflectors to correct rotation errors. The TLS instrument extracted a 3-D point cloud model of the Merapi summit with 2.8 million data points. A major benefit of the TLS methodology is the high-resolution and precision in the field of view; however, shadowing effects are significant.

In order to solve the shadow effects, we applied a structure from motion (SfM) technique (Szeliski, 2011) to generate a 3-D model based on 2-D drone images that were acquired on 6 October 2015. We used a DJI Phantom drone that flew loops at a height of ∼140 m over the dome and took nadir photographs with 2 s regular interval and 12 megapixel resolution. These photographs were processed by using agisoft photoscan professional software to generate a 3-D point cloud model of the Merapi summit. We then combined the 3-D point clouds of TLS and SfM data by using point pair-picking registration method in Cloud Compare software. More details about the data acquisition and the processing of TLS and SfM data are described in Darmawan et al. (2017, 2018). The combined 3-D TLS-SfM point cloud was interpolated in ArcMap to generate a digital elevation model (DEM) with a resolution of 0.5 m. The DEM was used for geomorphological, topography and slope analysis.

To further investigate any changes related to structural instability, we conducted drone photogrammetry on 2 September 2017 by using a DJI Mavic pro drone. The drone flew ∼50 m above the dome, carried a camera with a resolution of 12 Megapixels and captured 408 aerial images. However, as strong degassing at the fumaroles limited visibility, 3-D point cloud reconstruction by using the SfM–multiple virtual storage (MVS) technique was very noisy. The aerial images acquired in 2017 were used to generate photomosaic image and were qualitatively compared to the 2015 aerial images for structural analysis and for alteration mapping.

As we mapped the structural architecture of the lava dome, we are also interested in alteration and fumarole activities. Fractures and lithology contrasts may lead to permeability differences that control the pathways of thermal fluids (Ball and Pinkerton, 2006). We recorded apparent temperature distribution of the Merapi lava dome by using a forward-looking infrared (FLIR) P660 thermal camera in September 2014. Images were taken from the eastern crater rim close to the TLS station (Fig. 1b). The FLIR camera operates on a spectral band of 7.5–13 µm which allows us to identify an apparent temperature which was calibrated in a range of 0–500 ∘C. The resolution of the FLIR cameras is 640×480 pixels. The FLIR camera is equipped with a 7∘ (f=131) zoom lens with a 0.38 mrad instantaneous field of view (Walter et al., 2013a), allowing generation of very detailed and high-resolution thermal images, with estimated pixel dimensions of 1 px = 0.05 m on the dome center.

Thermal infrared data is dependent on a number of environmental parameters, such as the distance and emissivity of the target (the dome), the solar reflection, the viewing angle, the atmospheric effect and the presence of particles/gases in the electromagnetic radiation path (Spampinato et al., 2011). We recorded the thermal images during night time (05:00 am local time), so that background temperature was low, and insulation artefacts and solar reflection were minimized. Other factors were solved in data processing by setting the emissivity and transmissivity values to 0.98 and 0.7, respectively, following Carr et al. (2016) and Ball and Pinkerton (2006). Relative humidity was set to 45 % according to weather observation. The relative distance to the dome was 300 m on average and the background temperature was assumed to be 10 ∘C. After defining the parameters, the thermal images were set to constant color scales for all images and then were mosaicked to obtain a high-resolution panorama image of the apparent thermal distribution of the Merapi lava dome.

2.2 Factor of safety (FS)

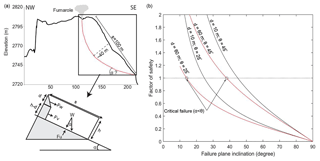

Factor of safety is widely used to assess slope stability by estimating the load carrying capacity of a flank. The factor of safety describes if a system is stronger or weaker for the given load. It is affected, in our case, by rainfall, and has been applied for numerous engineering problems (Aleotti and Chowdhury, 1999). On dome building volcanoes, the factor of safety calculation allows for estimating slope instability during precipitation events, as dome collapse events are favored by heavy rainfall (Yamasato et al., 1998; Elsworth et al., 2004). Here, we follow the work of Simmons et al. (2004) and test the instability of the southern sector of the Merapi lava dome during intense rainfall by first estimating how deep rainwater is able to percolate (d) through identified fractures:

where i is the rain intensity as measured by a proximal weather station, and ΔTw is the required thermal energy to vaporize water, ΔTR is the required thermal energy to cool the fracture surface, ρR and ρw are the density of lava dome rock and water, respectively, KR is thermal diffusivity, tD is a non-dimensional time which is described as , t is the rainfall duration, , cW and cR are heat capacity of water and rock, respectively. The estimated of water percolation (d) is then used to calculate the factor of safety:

where C is the cohesive strength, W (unstable dome sector weight) = and s is the fracture spacing, h is the unstable dome sector thickness, α is the inclination of failure plane, θ is friction angle and g is the gravitational force. During intense rainfall, rainwater is able to percolate through identified fractures, interacting with the hot interior of the lava dome, thus increasing degassing activity and then generating water forces (Fw ), uplift force from the volcanic gas (Fu and vaporized water force (Fv ; Fig. 7a), where ρg is the density of gas. A result of FS ≤1 indicates a potential failure, whilst a FS larger than 1 describes a stable condition.

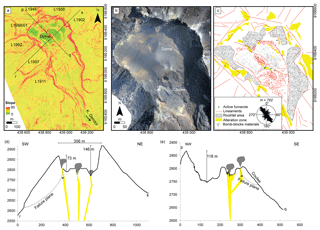

Factor of safety calculation requires careful parameter justification. For the parameters, we consider the rain gauge data that recorded by hydro-meteorological stations around Merapi volcano, and set the rainfall intensity (i) to 10–100 mm h−1. The fracture spacing (s) is 100 m and mimics a translational fault with hanging wall thickness (h) of ∼40 m (Fig. 7a). The temperature gradient from the surface to the dome interior (ΔTw) is 200–800 ∘C, which is based on our thermal data and thermodynamic models of the lava dome interior (Matthews and Barclay, 2004). Friction angle is from 25 to 45∘, which is on the range of friction for rock on rock material (Husain et al., 2014; Simmons et al., 2004). The density of Merapi rock is 2242 kg m−3 (Tiede et al., 2005). As the rock is progressively altered, we assume that the dome rock is homogenous and has cohesion strength of 10 MPa, following studies of rock strength of altered rock from Mayer et al. (2016); Pola et al. (2014). Details of the parameters used to calculate the factor of safety and water percolation are listed in Table 1 and a critical discussion of the parameters can be found in Sect. 4.1.

2.3 Scenario modeling of block-and-ash flows

Based on analysis of geomorphology, structure and factor of safety, we are able to identify potential hazards. We then simulated a hazard scenario of gravity driven avalanches by using Titan2D software. The Titan2D software has been used by previous studies to simulate block-and-ash flows due to lava dome collapses (Widiwijayanti et al., 2007; Charbonnier and Gertisser, 2009; Procter et al., 2009; Charbonnier and Gertisser, 2012; Charbonnier et al., 2013). The input parameters of Titan2D should be defined carefully to reduce uncertainty during simulation and to obtain the most realistic result. For parameterization, the volume of the collapse is based on the structurally delineated southern dome sector. The collapse volume is set to 0.3×106 m3, which represents a deep water percolation and gentle slope failure plane (α) scenario. The bed coulomb friction parameter, the most sensitive parameter that controls the flow and material distribution (Sheridan et al., 2005; Charbonnier and Gertisser, 2009), is set to between 28 and 16∘, from the top of the dome to the lowest slope, respectively (Table 2), following a study of single dome collapses after the 14 June 2006 eruption (Charbonnier and Gertisser, 2009). This range of the bed friction parameter will consider the topography effect during simulation and produce realistic mass flow model. The initial velocity is set to 0 m s−1 as we assume that the failure mechanism is not involving large magmatic pressure. We used the updated digital elevation model of the Merapi summit from our TLS and drone photogrammetry data and extended it in the far field by merging it with the published 2005 digital elevation model (Gerstenecker et al., 2005). A full set of parameters used for Titan2D simulation is listed in Table 2 and the limitations of Titan2D are discussed in Sect. 4.1.

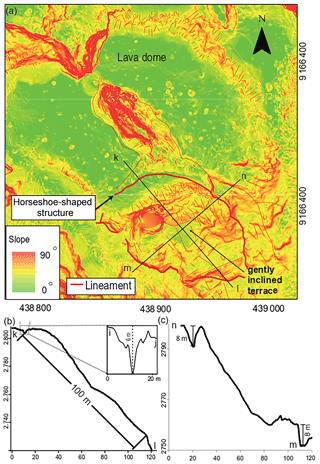

Figure 3(a) Detailed slope map of the Merapi lava dome that shows that the top of the dome is relatively flat. The fissure and the northern part of the dome are steeply inclined with a slope of ≥80∘. The southern block possibly consists of two different flow units which are separated by a gently inclined terrace. A cross section of the lines (b) k-l and (c) m-n that shows that the horseshoe-shaped structure has a maximum depth of 8 m.

3.1 Geomorphology and structure of the Merapi summit

The high-resolution slope map and the photomosaic show the geomorphology and structure of the Merapi summit (Fig. 2). The 2010 explosive eruption formed a deep crater that opened in the southeast direction and is surrounded by old domes with slopes of 45∘. Shortly after the 2010 eruption, a lava dome formed at the middle of the crater. The deep crater is steeply inclined with a slope of ∼80∘ and has a diameter of 356 m, a maximum depth of 118 m at the northwest crater wall, 146 m at the northeast crater wall and 73 m at the southwest crater wall, as shown in cross section of lines p-q and r-s (Fig. 2a, d and e). The high-resolution drone photomosaic clearly shows that the summit is highly fractured with an azimuth of N150∘ E and shows fumarole activity and yellowis sulfur deposition, especially around the crater wall (Fig. 2b and c). A remnant of altered rocks after the 2010 eruption is exposed at the north crater wall and southeast basal surface. Degassing activity is identified at the fissure area, southern dome, west crater wall and northeast crater (green points in Fig. 2c). This degassing activity causes progressive hydrothermal alteration that may weaken and destabilize the dome rock. Some of the altered rocks on the crater wall fall and produce gravity driven rock falls that are deposited inside the crater. Some materials of the 2012–2014 explosions are also deposited inside the crater and on the top of the lava dome (Fig. 2c).

Further analysis of the slope and structure of the lava dome shows that the top of the dome is relatively flat, while the open fissure is steeply inclined with slope of ∼80∘. A horseshoe-shaped fault-like structure is identified and it delineates a block in the southern dome sector (Fig. 3a). The structure can be traced for a length of over 165 m and the block has dimensions of 100 m ×80 m. The cross section profiles of line k-l and m-n show that the maximum depths of the horseshoe-shaped fault structure in the northwest, northeast and southwest are 6, 8 and 3 m, respectively (Fig. 3b and c). The delineated block is steeply inclined at ∼50∘, hosts abundant fractures, has a blocky appearance and consists of two or three steep regions, which are separated by gently inclined terraces that may indicate different flow units as also observed from the drone aerial image (Figs. 3a and 4a). As the unstable dome sector is located on a steep slope (Fig. 3a), it is critical to monitor changes on the southern part of the Merapi dome.

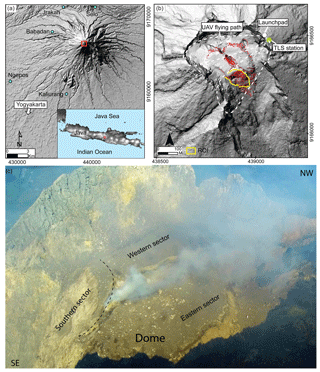

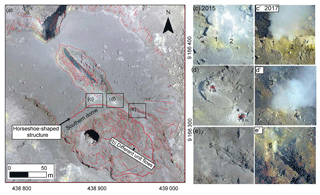

Figure 4(a) Photomosaic of UAV aerial images acquired in 2015 that shows detailed structures on the Merapi lava dome. The dome is highly fractured at the fissure area, at the dome margin and on the southern dome. (b) A different unit flow and three fracture areas (c, d and e) are clearly identified by our photomosaic drone aerial images. Coordinates are in UTM. Zoomed images of drone images between 2015 and 2017 at those three fractures area show a mechanical weakening due to hydrothermal alteration, especially at the fracture number 5 (area e–e'). We estimate that the diameter of the first, second, third, fourth and fifth fractures is 0.7, 0.3, 1, 1.3 and 0.3 m, respectively.

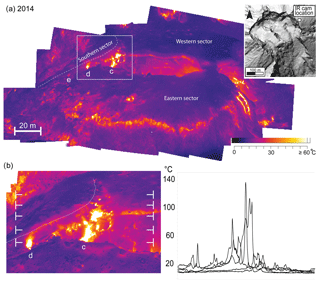

Figure 5(a) Photomosaic of high-resolution thermal images taken from the eastern flank (inset) shows the variation of apparent thermal variation of the Merapi dome in 2014. (b) We find high temperatures around ≥140 ∘C at the horseshoe-shaped structure and along the fracture area of c, d and e as identified by our drone camera. High thermal pixel value may indicate a hydrothermal fluid activity that can progressively alter and ultimately weaken the dome.

Close-range aerial images show more details of the horseshoe-shaped structures and the southern block (Fig. 4). We find five fractures in three different areas (c, d and e). A closer view of those fractures (first, second, fourth and fifth) reveals that they have a width of 0.3–1.3 m (Fig. 4c, d and e). Comparison of drone aerial images between 2015 and 2017 shows a progressive hydrothermal alteration processes around those fractures within just 2 years. The yellow color surrounding the active fractures indicates sulfur deposit around the fumaroles, which are stronger expressed in the 2017 images, especially around the fracture number 5 (area e-e'). It may indicate a structural weakening due to hydrothermal alteration. The hydrothermal activities at the horseshoe-shaped structure are also observed by our thermal camera, which is described below.

3.2 Thermal variation of the Merapi dome

Forward-looking infrared thermal mapping allows identification of the apparent temperature of the dome surface and the main regions of hydrothermal fluid-flow on the horseshoe-shaped structure. We find that the mean apparent temperature at the dome surface is about 6–14 ∘C (Fig. 5a). The low apparent temperature of the dome surface is related to data acquisition that is performed at night and the insulating ash deposits that covered the dome during six distinct phreatic explosions that occurred between 2012 and 2014 (Darmawan et al., 2018). The highest apparent temperatures are found at the northern margins of the dome with a maximum temperature of 201.7 ∘C. The high-resolution of 1 px = 0.05 m in the 2014 thermal data allowed further investigation of the horseshoe-shaped structure in more detail. We show the thermal fingerprint of the fractures in three areas, c, d and e, with a maximum apparent temperature of 161, 150 and 31 ∘C, respectively (Fig. 5b). The cross section temperature profile of the horseshoe-shaped structure (Fig. 5b) shows a strong thermal signal in the horseshoe-shaped structure, which indicates a prominent pathway for hydrothermal fluids.

We repeated the thermal mapping campaign of the lava dome 3 years later (September 2017). The apparent temperature of fracture number 5 (area e) increased from 31 up to ∼70 ∘C, which may indicate an increase of hydrothermal fluid activity in fracture number 5 (area e). The increasing of thermal activity in fracture 5 (area e) is highly correlated with the increase of hydrothermal alteration activity as observed by drone images in 2017 (Fig. 4e-e'). However, as the thermal cameras used in 2014 and 2017 are different, the results cannot be directly compared. More details on this repeat thermal mapping can be found in the Supplement.

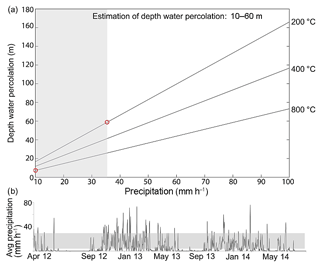

Figure 6(a) Depth of rainwater percolation, as a function of rainfall intensity at Merapi, is controlled by the temperature of the dome. By assuming the minimum and maximum temperature of the dome of 200 and 800 ∘C, respectively, the estimation of depth water percolation is 10 to 60 m (red circles) during typical rainfall (grey area). (b) The typical intensity of rainfall from April 2012 to July 2014 was 10–35 mm h−1 (grey area) and was calculated based on average rain intensity from five observatories near Merapi (see Fig. 1a).

3.3 Factor of safety results

Assessment of factor of safety during intense rainfall first requires quantification of the effect of rainwater. Based on a typical rainfall event (intensity of 10–35 mm h−1) and assuming a rain duration of ∼3 h, we calculate the rainwater percolation between 10 and 60 m by using Eq. (1) (Fig. 6). The 10 and 60 m depth water percolation are then used to calculate the factor of safety as a function of failure plane inclination (Fig. 7). Results show that failure (FS ≤1) may occur when the failure plane is 25 and 45∘ (α≥θ) during shallow water percolation (10 m) scenario (black lines in Fig. 7b). It indicates that friction (θ) controls the stability during shallow water percolation. For the deep water percolation scenario (60 m), the plane inclinations at failure mode (FS ≤1) are 15 and 39∘ for friction angles (θ) of 25 and 45∘, respectively (red lines in Fig. 7b). This indicates that friction cannot resist the total driving forces when rainwater percolates deeply. Calculation of the factor of safety reveals that the delineated dome sector is particularly unstable during deep water percolation (d∼60 m). Using a basal inclination of 15∘, the estimated unstable rock volume during intense rainfall events is 0.3×106 m3.

Figure 7(a) Cross section of the Merapi lava dome shows that the horseshoe-shaped structure may develop into a translational fault with fracture spacing (s) up to 100 m and a hanging wall thickness of ∼40 m. The stability of the unstable dome sector is influenced by the weight (W), water force (FW), vaporized water force (FV) and gas uplift force (Fu) along the fault boundary during intense rainfall (Modified from Simmons et al., 2004). (b) Analysis of factor of safety for the southern dome sector shows that deep water percolation (red lines) may reduce failure plane inclination and failure may occur even if the failure plane is inclined gently below the friction angle (α<θ).

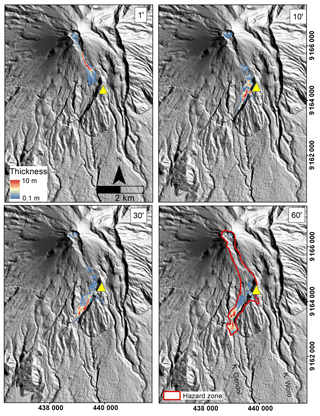

Figure 8Result of the numerical simulation of the pyroclastic block-and-ash flow that may form due to the collapse of the delineated southern dome sector after 1, 10, 30 and 60 min. The block-and-ash flow is deflected by the Kendil hills (yellow triangle) within ∼1 min after the collapse. The red outline indicates the total inundation zone as a result of the deposition of the block-and-ash flow material. Coordinates are in UTM meters.

3.4 Scenario numerical model of block-and-ash flows

The estimated volume is now used as an input for the Titan2D simulation. Titan2D simulation results show that the debris material mobilizes down into the southeastern valley and will reach 1.9 km from the summit at the first minute (Fig. 8). After 10 min, the debris materials are deflected by the Kendil hills (yellow triangle) and the main flow travels further to Gendol river valley with distance of 2.6 km from the summit. Within 30 min, the main flow reaches a distance of 3.1 km and it continues to travel along Gendol river valley. The flow finally stops with a maximum runout distance of 3.6 km from the summit. Most of the material is deposited at the upstream of Gendol river with a maximum thickness of ∼10 m. The potential hazard area (red polygon) due to the small volume of the single dome collapse is 1.5 km2.

4.1 Limitations

We find some limitations during drone, TLS and thermal data acquisition due to the complexity and hazardous access at the Merapi summit after the 2010 explosive eruption. The drone was caught by turbulence due to fumarole activity and strong winds, and the TLS data could only be obtained from the eastern crater wall since a different scan position was too hazardous at the Merapi summit. Therefore, the TLS data have significant shadowing effects. However, the advantage of the TLS data is that it is highly accurate and the drone is able to cover the shadow area. The combination of TLS and drone photogrammetry is therefore able to generate a digital elevation model with a resolution of 0.5 m and a photomosaic with a resolution up to 0.03 m. We find that the combination of TLS and drone photogrammetry is robust and can be applied for geomorphology and structural mapping at steep sided dome building volcanoes.

The thermal variation was investigated by using a FLIR camera. Parameters such as emissivity, surface roughness, viewing angle, atmospheric effects, volcanic gas, instrumental errors, solar radiation and solar heating may affect the pixel value of the FLIR thermal images (Spampinato et al., 2011). The effect of solar radiation and solar heating was largely reduced by acquiring the FLIR data before sunrise. However, parameters of emissivity, transmissivity, relative humidity, distance and temperature background may be influential during data processing. We tested the sensitivity of these parameters and we found that emissivity is the most sensitive parameter. Increasing emissivity by 0.01 will reduce the apparent temperature by ∼1 ∘C. By assuming a range of emissivity between 0.95 and 0.98, which is common on dome building volcanoes (Merapi and Colima, Mexico; Walter et al., 2013a; Carr et al., 2016), we infer that our apparent temperature has an uncertainty of ∼3 ∘C. For the structural analysis performed, this is an acceptable range.

The degree of dome instability is estimated by using the factor of safety calculation, assuming an intense rainfall event similar to the study of Simmons et al. (2004), where the parameters of dome sector geometry (thickness and fracture spacing), temperature, the friction angle, the rock strength, and the intensity and duration of the rainfall may influence the result. Our factor of safety analysis is constrained for the southern Merapi dome sector. For this we hypothesize a fracture spacing (s) of 100 m, thickness (h) of 40 m, cohesive strength of 10 MPa following the studies of rock strength of altered rock from Mayer et al. (2016) and Pola et al. (2014), dome temperature of 200–800 ∘C during typical rainfall at Merapi (intensity of 10–35 mm h−1 and duration of ∼3 h) and friction angles of 25 and 45∘ (Simmons et al., 2004; Husein et al., 2014).

Our morphological analysis, thermal images and rainfall gauges provide realistic information of the fracture spacing (s), temperature to cool the dome (ΔTR) and rainfall intensity; however, the parameters of dome thickness, rainfall duration and the temperature required to vaporize rainwater (ΔTw) have some uncertainty. Here, we tested those parameters and found that the rainfall duration is the most sensitive parameter as it influences the depth of water percolation. Doubling the rainfall duration from 3 to 6 h with an intensity of 35 mm h−1 will increase the water percolation by up to 10 m, which will decrease the factor of safety by ∼0.09 and reduce the failure plane inclination (α) by 1∘, while the dome thickness and temperature required to vaporize the rain water (ΔTw) are not significantly affected. Doubling the block thickness reduces the factor of safety by ∼0.01 and reducing the temperature to vaporize the water (ΔTw) from 100 to 90 ∘C only increases the factor of safety by ∼0.006. By assuming rainfall duration of 12 h during the rainy season, we estimate the failure plane inclination have an uncertainty of ±3∘ that may affect the uncertainty of the volume of the collapsing block by ±65.000 m3. We also assume that the rock cohesion is homogenous, while our drone photomosaic data shows that the degree of alteration that may influence the rock cohesion is spatially varied. We then further analyzed the factor of safety with heterogeneous rock cohesion in Sect. 4.3.

In a case of dome sector failure, the potential hazard zone is estimated by usingTitan2D software. Our Titan2D model represents an approximation of runout distance, deposit and potential hazard area due to single small volume dome collapses. However, Titan2D is not able to model pyroclastic surges. The pyroclastic surges that occurred and jumped over Kendil hills during the 2010 eruption could not be modeled by Titan2D as surges are diluted, mixed with gas and the propagation is not controlled by topography (Charbonnier et al., 2013). In order to solve the propagation of pyroclastic surge, a two-layer model has been proposed by assuming that pyroclastic density currents (PDCs) consist of two distinct layers, a concentrated layer (block-and-ash flow) and a diluted layer (ash-cloud surge; Kelfoun et al., 2017). The mobility of each layer is solved by using a depth-averaged algorithm. Results of this model were successful in simulating the mobility of pyroclastic density currents of the Merapi eruption in 26 October and 5 November 2010.

Other limitations of Titan2D are the grain interactions which are controlled and simply solved by coulomb frictions (bed and internal); while in reality, the interaction of grains in pyroclastic density currents is complex, as the grains size varies and the momentum produced by this interaction is able to transport large lithics over great distances (≥10 km; Dufek et al., 2009). A study of grains size of pyroclastic flow also suggests that finer grain size may produce a higher mobility of the center of the mass flow (Cagnoli and Piersanti, 2015, 2017). As the grains interaction is only controlled by coulomb frictions in Titan2D, adjustment of coulomb frictions should be taken carefully and we used validated coulomb frictions from Charbonnier et al. (2012) in this study to obtain a reliable result.

4.2 Geomorphology and structural instability at the Merapi summit

The current morphology and structure on the Merapi dome show progressive hydrothermal alteration that may cause structural weakening. Previous studies show that hydrothermal alteration is able to weaken the dome rock up to 0.2–10 MPa (Pola et al., 2014; Wyering et al., 2014) and promotes a failure even during quiescence periods (Lopez and Williams, 1993; Reid et al., 2001). Our alteration, thermal and structural mapping datasets show that the southern Merapi dome and southwestern Merapi flank area are subjected to structural mechanical weakening. The southern dome sector is delineated by a curved horseshoe-shaped structure which was already identified even before the 2012–2014 explosions (Darmawan et al., 2018). The structure then became more strongly expressed and gradually deepened during the 2012–2014 explosions. The horseshoe-shaped structure is now 8 m deep, highly fractured and provides pathways for fumaroles as identified by thermal camera. The presence of progressive hydrothermal alteration in fracture 5 (area E) probably points to a mechanical weakening and future structural instability due to hydrothermal alteration.

Whether the altered fractures are deep reaching or not, however, is difficult to quantify. Our data only identify alteration at the surface and our model assumes that the horseshoe-shaped fracture is deeply altered and may transform to a translational fault due to lateral progressive hydrothermal alteration processes. Imaging the failure plane is challenging at the Merapi summit. Resistivity tomography could only be realized at elevation of 2400 m (400 below the Merapi summit) at the southern flank of Merapi and found a hydrothermal system at a depth of 200 m (Byrdina et al., 2017). If alteration progressively occurs at a depth of 200 m and gradually forms a failure plane, the southern dome and southwestern flank may be prone to serious structural weakening and instability due to hydrothermal alteration.

Progressive hydrothermal alteration also intensively occurs at the open fissure area. The open fissure is highly fractured, actively degassing and intensively altered, as shown from our drone photomosaic image (Fig. 2b). The latest eruption in May 2018 occurred at the fissure area. Although no seismic or deformation precursors were observed, the thermal signal dramatically increased 15 min before the eruption along the fissure area (BPPTKG, 2018b). Further analysis of eruption material suggests that the May 2018 eruption contained an abundance of altered materials, which indicates that the open fissure area is structurally already weakened due to hydrothermal alteration. The weakened structure thus provides a pathway to release gas overpressure and controls the location of the steam explosion in May 2018.

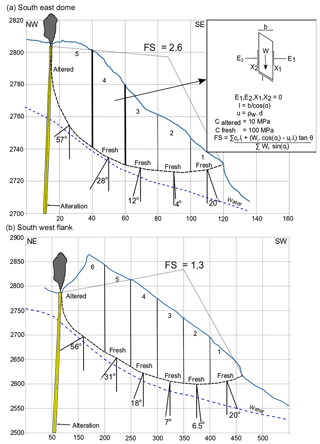

Figure 9Conceptual model of slope stability shows the geometry of (a) the southern Merapi dome sector and (b) the southwestern Merapi flank. The hydrothermal alteration along the fracture, the estimation of ground water and the heterogeneity of the rock cohesion are also indicated. Our calculation of factor of safety by using the Fellenius method shows that the southern dome is relatively stable (FS = 2.6), while the southwestern Merapi flank is approaching a warning (FS = 1.3) and requires further monitoring and assessment.

4.3 Implications for future dome failure

Geomorphology and structural mapping imply a structural weakening on the southern dome, at the open fissure and at western crater wall. Results of factor of safety calculations show that deep water percolation may reduce the friction and may increase hydrothermal alteration that further weakens the dome structure. However, our results of factor of safety assume that the rock cohesion strength is homogenous, while in fact, the rock cohesion strength is probably heterogeneous as the magnitude of alteration and associated cohesion strength is spatially varied. Therefore, we further analyzed the stability of the dome by using Fellenius (ordinary slice) factor of safety and varying the rock cohesion strength. Fellenius factor of safety is widely used to analyze slope stability and the method assumes that the mass above the failure plane is divided into n slices and the external forces (vertical shear and horizontal forces, Xn and En, respectively) are zero (Fig. 9). The acting forces on each slice are the weight, pore pressure (u) and rock cohesion (c), respectively (Fig. 9a inset). We assume that the rock cohesion at basal failure is heterogeneous. The rock cohesion which located close to the altered fracture is 10 MPa, while the rock cohesion of fresh rock is 100 MPa (Pola et al., 2014; Wyering et al., 2014) and the water deeply percolates (≥60 m; Fig. 9). We find that the factor of safety on the southern dome is 2.6 (Fig. 9a) which indicates a stable condition. We infer that fresh rock is strong enough to resist and to stabilize the dome. The factor of safety of the southwestern flank is 1.3 which may indicate a warning condition. We therefore also recommend monitoring the stability of the southwestern flank as historically the southwestern flank has frequently collapsed over the past decades.

Other factors, such as a new magma extrusion and gas overpressure, may also destabilize and trigger a dome failure. Gas pressurization may promote deep-seated failure and explosive eruptions, while slow rate magma extrusion can gradually make the dome overly steep and trigger gravitational collapses (Voight and Elsworth, 2000).

Currently, a new dome is growing at the middle of open fissure with volume of 135 000 m3 and extrusion rate of 0.01 m3 s−1 (BPPTKG, 2018a). The extrusion of a new dome involves degassing activity that increases hydrothermal alteration in the southern dome sector. Further investigation of the interaction of the new dome extrusion and structural weakening is now required.

4.4 Block-and-ash flow hazard along the Gendol valley

Our simulation of block failure and mobility along the Gendol valley shows the potential hazard due to structural weakening on the southern dome. The southern dome, with a volume of m3, may fail and produce block-and-ash flow with a maximum runout distance of 3.6 km and an affected hazard area of 1.5 km2. This runout distance is typical for a single dome collapse with a volume of ≤106 m3 (VEI =1). The single dome collapse in 2006 with a volume of 1×106 m3 traveled along Gendol valley and destroyed the village of Kaliadem which was located 4.5 km from the summit (Charbonnier and Gertisser, 2009; Ratdomopurbo et al., 2013). Therefore, we infer that our potential hazard model is relevant and realistic for single dome collapse with VEI 1. However, we did not consider the potential collapses of the new lava dome that is currently forming at the open fissure and is growing above the frozen lava dome. As the current morphology of the Merapi summit that opened to the Gendol valley (south–southeast), we infer that the new lava dome could potentially collapse into the Gendol valley due to magma intrusion, gravitational instability, gas overpressure, structural weakening, intense rainfall and earthquakes. We recommend to further monitor and investigate the potential hazard of the new lava dome in the near future.

Detailed morphological and structural studies of the active Merapi volcano reveal a structural weakening due to hydrothermal alteration on the southern dome. We identify a 165 m long horseshoe-shaped structure with a depth of 6 m that encircles the southern dome sector which has volume of m3. The structure is highly fractured and provides pathways for hydrothermal fluids which can lead to structural instability.

Our results from factor of safety calculations indicate that intense rainfall events at the Merapi summit are able to reduce the failure plane inclination. The southern dome may fail due to new activities or mechanical weakening. By using Titan2D flow simulation we estimate that the collapse of the unstable dome sector may produce block-and-ash flow that travels southward with a maximum runout distance of ∼4 km from the summit.

Data are available with the GFZ data service with DOI https://doi.org/10.5880/GFZ.2.1.2017.003 (Darmawan et al., 2017).

The supplement related to this article is available online at: https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-18-3267-2018-supplement.

HD collected the drone dataset, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper under supervision of TRW and VRT. TRW collected the infrared data and wrote and improved the paper. VRT wrote and improved the paper. ABS provided the rainfall dataset.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

This is a contribution to VOLCAPSE, which is a research project funded by the

European Research Council under the European Union's H2020 Programme/ERC

consolidator grant ERC-CoG 646858. The authors also acknowledge a scholarship

grant from Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst (DAAD), Germany, reference

no. 91525854, a research grant by the Swedish Research Council (VOLTAGE

project) and financial support by the Swedish Center for Natural Hazard and

Disaster Sciences (CNDS). We would like to also thank Mehdi Nikkhoo and

Nicole Richter for the data acquisition of the terrestrial laser scan,

Michele Pantaleo for the data acquisition of thermal images in 2014, and

Edgar Zon for supporting the 2014 fieldwork. We also thank François

Beauducel for supporting FLUKE camera recording during fieldwork in 2017 and

special thanks goes to BPPTKG (Merapi Volcano Observatory) for all of their

support during fieldwork in 2014, 2015 and 2017. We also thank Sylvain

Charbonnier and an anonymous referee for their constructive

review.

The article processing

charges for this open-access

publication were covered by a

Research

Centre of the Helmholtz Association.

Edited by: Giovanni Macedonio

Reviewed by:

Sylvain Charbonnier and one anonymous referee

Aleotti, P. and Chowdhury, R.: Landslide hazard assessment: summary review and new perspectives, B. Eng. Geol. Environ., 58, 21–44, 1999.

Ball, J. L., Stauffer, P. H., Calder, E. S., and Valentine, G. A.: The hydrothermal alteration of cooling lava domes, B. Volcanol., 77, 1–16, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00445-015-0986-z, 2015.

Ball, M. and Pinkerton, H.: Factors affecting the accuracy of thermal imaging cameras in volcanology, J. Geophys. Res., 111, 1–18, https://doi.org/10.1029/2005jb003829, 2006.

Bishop, A. W.: The use of the slip circle in the stability analysis of slopes, Geotechnique, 5, 7–17, 1955.

BPPTKG.: Laporan aktivitas Gunung Merapi tanggal 28 September–4 Oktober 2018, access: 12 October, 2018a.

BPPTKG.: Diskusi Scientific Forum: Kajian Erupsi Freatik G. Merapi 11 Mei 2018, access: 12 October, 2018b.

Byrdina, S., Friedel, S., Vandemeulebrouck, J., Budi-Santoso, A., Suhari, Suryanto, W., Rizal, M. H., Winata, E., and Kusdaryanto: Geophysical image of the hydrothermal system of Merapi volcano, J. Volcanol. Geoth. Res., 329, 30–40, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2016.11.011, 2017.

Cagnoli, B. and Piersanti, A.: Grain size and flow volume effects on granular flow mobility in numerical simulations: 3-D discrete element modeling of flows of angular rock fragments, J. Geophys. Res.-Sol. Ea., 120, 2350–2366, https://doi.org/10.1002/2014jb011729, 2015.

Cagnoli, B. and Piersanti, A.: Combined effects of grain size, flow volume and channel width on geophysical flow mobility: three-dimensional discrete element modeling of dry and dense flows of angular rock fragments, Solid Earth, 8, 177–188, https://doi.org/10.5194/se-8-177-2017, 2017.

Calder, E. S., Lavallé, Y., Kendrick, J. E., and Bernstein, M.: Lava Dome Eruptions, in: The encyclopedia of volcanoes 2nd edition, edited by: Sigurdsson, H., Houghton, B., Mc Nutt, R. S., Rymer, H., and Stix, J., Elsevier, United States, 343–362, 2015.

Carr, B. B., Clarke, A. B., and Vanderkluysen, L.: The 2006 lava dome eruption of Merapi Volcano (Indonesia): Detailed analysis using MODIS TIR, J. Volcanol. Geoth. Res., 311, 60–71, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2015.12.004, 2016.

Carr, B. B., Clarke, A. B., and de' Michieli Vitturi, M.: Earthquake induced variations in extrusion rate: A numerical modeling approach to the 2006 eruption of Merapi Volcano (Indonesia), Earth Planet. Sc. Lett., 482, 377–387, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2017.11.019, 2018.

Charbonnier, S. J. and Gertisser, R.: Numerical simulations of block-and-ash flows using the Titan2D flow model: examples from the 2006 eruption of Merapi Volcano, Java, Indonesia, B. Volcanol., 71, 953–959, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00445-009-0299-1, 2009.

Charbonnier, S. J. and Gertisser, R.: Evaluation of geophysical mass flow models using the 2006 block-and-ash flows of Merapi Volcano, Java, Indonesia: Towards a short-term hazard assessment tool, J. Volcanol. Geoth. Res., 231–232, 87–108, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2012.02.015, 2012.

Charbonnier, S. J., Germa, A., Connor, C. B., Gertisser, R., Preece, K., Komorowski, J. C., Lavigne, F., Dixon, T., and Connor, L.: Evaluation of the impact of the 2010 pyroclastic density currents at Merapi volcano from high-resolution satellite imagery, field investigations and numerical simulations, J. Volcanol. Geoth. Res., 261, 295–315, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2012.12.021, 2013.

Darmawan, H., Walter, T. R., Brotopuspito, K. S., Subandriyo, and Nandaka, I. G. M. A.: Morphological and structural changes at the Merapi lava dome monitored in 2012–15 using unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), J. Volcanol. Geoth. Res., 349, 256–267, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2017.11.006, 2018.

Darmawan, H., Walter, T., Richter, N., and Nikkoo, M.: High resolution Digital Elevation Model of Merapi summit in 2015 generated by UAVs and TLS, V. 2015 GFZ Data Services, https://doi.org/10.5880/GFZ.2.1.2017.003, 2017.

Dufek, J., Wexler, J., and Manga, M.: Transport capacity of pyroclastic density currents: Experiments and models of substrate-flow interaction, J. Geophys. Res.-Sol. Ea., 114, 1–13, https://doi.org/10.1029/2008jb006216, 2009.

Elsworth, D., Voight, B., Thompson, G., and Young, S. R.: Thermal-hydrologic mechanism for rainfall-triggered collapse of lava domes, Geology, 32, 969–972, https://doi.org/10.1130/g20730.1, 2004.

Gerstenecker, C., Läufer, G., Steineck, D., Tiede, C., and Wrobel, B.: Validation of Digital Elevation Models around Merapi Volcano, Java, Indonesia, Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci., 5, 863–876, https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-5-863-2005, 2005.

Girona, T., Costa, F., Taisne, B., Aggangan, and Ildefonso, S.: Fractal degassing from Erebus and Mayon volcanoes revealed by a new method to monitor H2O emission cycles, J. Geophys. Res.-Sol. Ea., 120, 2988–3002, https://doi.org/10.1002/2014JB011797, 2015.

Hale, A. J.: Lava dome growth and evolution with an independently deformable talus, Geophys. J. Int., 174, 391–417, 2008.

Hamilton, W.: Tectonics of the Indonesian Region, U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1078, United States Government Printing Office, Washington, 1979.

Husain, T., Elsworth, D., Voight, B., Mattioli, G., and Jansma, P.: Influence of extrusion rate and magma rheology on the growth of lava domes: Insights from particle-dynamics modeling, J. Volcanol. Geoth. Res., 285, 100–117, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2014.08.013, 2014.

James, M. R. and Varley, N.: Identification of structural controls in an active lava dome with high resolution DEMs: Volcán de Colima, Mexico, Geophys. Res. Lett., 39, 1–5, https://doi.org/10.1029/2012gl054245, 2012.

Kelfoun, K., Gueugneau, V., Komorowski, J. K., Aisyah, N., Cholik, N., and Merciecca, C.: Simulation of block-and-ash flows and ash-cloud surges of the 2010 eruption of Merapi volcano with a two-layer model, J. Geophys. Res.-Sol. Ea., 122, 4277–4292, https://doi.org/10.1002/2017JB013981, 2017.

Kubanek, J., Westerhaus, M., Schenk, A., Aisyah, N., Brotopuspito, K. S., and Heck, B.: Volumetric change quantification of the 2010 Merapi eruption using TanDEM-X InSAR, Remote Sens. Environ., 164, 16–25, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2015.02.027, 2015.

Lavigne, F., Morin, J., and Surono: The atlas of Merapi Volcano, Laboratoire de Geographie Physique, CNRS UMR, France, 2015.

Lopez, D. L. and Williams, S. N.: Catastrophic volcanic collapse: relation to hydrothermal processes, Science, 260, 1794–1796, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.260.5115.1794, 1993.

Matthews, A. J. and Barclay, J.: A thermodynamical model for rainfall-triggered volcanic dome collapse, Geophys. Res. Lett., 31, 1–4, https://doi.org/10.1029/2003gl019310, 2004.

Mayer, K., Scheu, B., Montanaro, C., Yilmaz, T. I., Isaia, R., Aßbichler, D., and Dingwell, D. B.: Hydrothermal alteration of surficial rocks at Solfatara (Campi Flegrei): Petrophysical properties and implications for phreatic eruption processes, J. Volcanol. Geoth. Res., 320, 128–143, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2016.04.020, 2016.

Norton, G. E., Watts, R. B., Voight, B., Mattioli, G. S., Herd, R. A., Young, S. R., Devine, G. E., Aspinall, W. P., Bonadonna, C., Baptie, B. J., Edmonds, M., Jolly, A. D., Loughlin, S. C., Luckett, R., and Sparks, R. S. J.: Pyroclastic flow and explosive activity at Soufriere Hills Volcano, Montserrat, during a period of virtually no magma extrusion (March 1998 to November 1999), Geological Society, London, Memiors, 21, https://doi.org/10.1144/GSL.MEM.2002.021.01.21, 2002.

Pallister, J. S., Schneider, D. J., Griswold, J. P., Keeler, R. H., Burton, W. C., Noyles, C., Newhall, C. G., and Ratdomopurbo, A.: Merapi 2010 eruption – Chronology and extrusion rates monitored with satellite radar and used in eruption forecasting, J. Volcanol. Geoth. Res., 261, 144–152, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2012.07.012, 2013.

Patra, A. K., Bauer, A. C., Nichita, C. C., Pitman, E. B., Sheridan, M. F., Bursik, M., Rupp, B., Webber, A., Stinton, A. J., Namikawa, L. M., and Renschler, C. S.: Parallel adaptive numerical simulation of dry avalanches over natural terrain, J. Volcanol. Geoth. Res., 139, 1–21, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2004.06.014, 2005.

Pola, A., Crosta, G. B., Fusi, N., and Castellanza, R.: General characterization of the mechanical behaviour of different volcanic rocks with respect to alteration, Eng. Geol., 169, 1–13, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2013.11.011, 2014.

Procter, J. N., Cronin, S. J., Platz, T., Patra, A., Dalbey, K., Sheridan, M., and Neall, V.: Mapping block-and-ash flow hazards based on Titan 2-D simulations: a case study from Mt. Taranaki, NZ, Nat. Hazards, 53, 483–501, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-009-9440-x, 2009.

Ratdomopurbo, A., Beauducel, F., Subandriyo, J., Agung Nandaka, I. G. M., Newhall, C. G., Suharna, Sayudi, D. S., Suparwaka, H., and Sunarta: Overview of the 2006 eruption of Mt. Merapi, J. Volcanol. Geoth. Res., 261, 87–97, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2013.03.019, 2013.

Reid, M. E., Sisson, T. W., and Brien, D. L.: Volcano collapse promoted by hydrothermal alteration and edifice shape, Mount Rainier, Washington, Geology, 29, 779–782, 2001.

Rhodes, E., Kennedy, B. M., Lavallee, Y., Hornby, A., Edwards, M., and Chigna, G.: Textural insights into the evolving lava dome cycles at Santiaguito lava dome, Guatemala, Front. Earth Sci., 6, 1–18, https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2018.00030, 2018.

Richter, G., Wassermann, J., Zimmer, M., and Ohrnberger, M.: Correlation of seismic activity and fumarole temperature at the Mt. Merapi volcano (Indonesia) in 2000, J. Volcanol. Geoth. Res., 135, 331–342, 2004.

Salzer, J. T., Nikkhoo, M., Walter, T. R., Sudhaus, H., Reyes-Davila, G., Breton, M., and Arambula, R.: Satellite radar data reveal short-term pre-explosive displacements and a complex conduit system at Volcan de Colima, Mexico, Front. Earth Sci., 2, 1–11, https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2014.00012, 2014.

Salzer, J. T., Milillo, P., Varley, N., Perissin, D., Pantaleo, M., and Walter, T. R.: Evaluating links between deformation, topography and surface temperature at volcanic domes: Results from a multi-sensor study at Volcán de Colima, Mexico, Earth Planet. Sc. Lett., 479, 354–365, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2017.09.027, 2017.

Sheridan, M. F., Stinton, A. J., Patra, A., Pitman, E. B., Bauer, A., and Nichita, C. C.: Evaluating Titan2D mass-flow model using the 1963 Little Tahoma Peak avalanches, Mount Rainier, Washington, J. Volcanol. Geoth. Res., 139, 89–102, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2004.06.011, 2005.

Simmons, J., Elsworth, D., and Voight, B.: Instability of exogenous lava lobes during intense rainfall, B. Volcanol., 66, 725–734, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00445-004-0353-y, 2004.

Siswowidjoyo, S., Suryo, I., and Yokoyama, I.: Magma eruption rates of Merapi volcano, Central Java, Indonesia during one century (1890–1992), B. Volcanol., 57, 111–116, 1995.

Spampinato, L., Calvari, S., Oppenheimer, C., and Boschi, E.: Volcano surveillance using infrared cameras, Earth-Sci. Rev., 106, 63–91, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2011.01.003, 2011.

Surono, Jousset, P., Pallister, J., Boichu, M., Buongiorno, M. F., Budisantoso, A., Costa, F., Andreastuti, S., Prata, F., Schneider, D., Clarisse, L., Humaida, H., Sumarti, S., Bignami, C., Griswold, J., Carn, S., Oppenheimer, C., and Lavigne, F.: The 2010 explosive eruption of Java's Merapi volcano – A “100-year” event, J. Volcanol. Geoth. Res., 241–242, 121–135, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2012.06.018, 2012.

Szeliski, R.: Structure from motion, in: Computer Vision, Springer, London, 2011.

Taron, J., Elsworth, D., Thompson, G., and Voight, B.: Mechanisms for rainfall-concurrent lava dome collapses at Soufrière Hills Volcano, 2000–2002, J. Volcanol. Geoth. Res., 160, 195–209, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2006.10.003, 2007.

Thiele, S. T., Varley, N., and James, M. R.: Thermal photogrammetric imaging: A new technique for monitoring dome eruptions, J. Volcanol. Geoth. Res., 337, 140–145, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2017.03.022, 2017.

Tiede, C., Camacho, A. G., Gerstenecker, C., Fernández, J., and Suyanto, I.: Modeling the density at Merapi volcano area, Indonesia, via the inverse gravimetric problem, Geochem. Geophy. Geosy., 6, 1–13, https://doi.org/10.1029/2005gc000986, 2005.

Voight, B.: Structural stability of andesite volcanoes and lava domes, Philos. T. Roy. Soc. A, 358, 1663–1703, https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2000.0609, 2000.

Voight, B. and Elsworth, D.: Instability and collapse of hazardous gas-pressurized lava domes, Geophys. Res. Lett., 27, 1–4, 2000.

Voight, B., Constantine, E. K., Siswowidjoyo, S., and Torley, R.: Historical eruptions of Merapi Volcano, Central Java, Indonesia 1768–1998, J. Volcanol. Geoth. Res., 100, 69–138, 2000.

Walter, T. R., Wang, R., Zimmer, M., Grosser, H., Lühr, B., and Ratdomopurbo, A.: Volcanic activity influenced by tectonic earthquakes: Static and dynamic stress triggering at Mt. Merapi, Geophys. Res. Lett., 34, 1–5, https://doi.org/10.1029/2006gl028710, 2007.

Walter, T. R., Legrand, D., Granados, H. D., Reyes, G., and Arámbula, R.: Volcanic eruption monitoring by thermal image correlation: Pixel offsets show episodic dome growth of the Colima volcano, J. Geophys. Res.-Sol. Ea., 118, 1408–1419, https://doi.org/10.1002/jgrb.50066, 2013a.

Walter, T. R., Ratdomopurbo, A., Subandriyo, Aisyah, N., Brotopuspito, K. S., Salzer, J., and Lühr, B.: Dome growth and coulée spreading controlled by surface morphology, as determined by pixel offsets in photographs of the 2006 Merapi eruption, J. Volcanol. Geoth. Res., 261, 121–129, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2013.02.004, 2013b.

Walter, T. R., Subandriyo, J., Kirbani, S., Bathke, H., Suryanto, W., Aisyah, N., Darmawan, H., Jousset, P., Luehr, B. G., and Dahm, T.: Volcano-tectonic control of Merapi's lava dome splitting: The November 2013 fracture observed from high resolution TerraSAR-X data, Tectonophysics, 639, 23–33, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tecto.2014.11.007, 2015.

Widiwijayanti, C., Hidayat, D., Voight, B., Patra, A., and Pitman, E. B.: Modeling dome-collapse pyroclastic flows for crisis assessments on Montserrat with TITAN2D, Cities on Volcanoes 5, Shimabara, Japan, The volcanological Society of Japan, 11P34, 2007.

Wyering, L. D., Villeneuve, M. C., Wallis, I. C., Siratovich, P. A., Kennedy, B. M., Gravley, D. M., and Cant, J. L.: Mechanical and physical properties of hydrothermally altered rocks, Taupo Volcanic Zone, New Zealand, J. Volcanol. Geoth. Res., 288, 76–93, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2014.10.008, 2014.

Yamasato, H., Kitagawa, S., and Komiya, M.: Effect of rainfall on dacitic lava dome collapse at Unzen volcano, Japan, Pap. Meteorol. Geophys., 48, 73–78, 1998.