the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License.

Using kites for 3-D mapping of gullies at decimetre-resolution over several square kilometres: a case study on the Kamech catchment, Tunisia

Denis Feurer

Olivier Planchon

Mohamed Amine El Maaoui

Abir Ben Slimane

Mohamed Rached Boussema

Marc Pierrot-Deseilligny

Damien Raclot

Monitoring agricultural areas threatened by soil erosion often requires decimetre topographic information over areas of several square kilometres. Airborne lidar and remotely piloted aircraft system (RPAS) imagery have the ability to provide repeated decimetre-resolution and -accuracy digital elevation models (DEMs) covering these extents, which is unrealistic with ground surveys. However, various factors hamper the dissemination of these technologies in a wide range of situations, including local regulations for RPAS and the cost for airborne laser systems and medium-format RPAS imagery. The goal of this study is to investigate the ability of low-tech kite aerial photography to obtain DEMs with decimetre resolution and accuracy that permit 3-D descriptions of active gullying in cultivated areas of several square kilometres. To this end, we developed and assessed a two-step workflow. First, we used both heuristic experimental approaches in field and numerical simulations to determine the conditions that make a photogrammetric flight possible and effective over several square kilometres with a kite and a consumer-grade camera. Second, we mapped and characterised the entire gully system of a test catchment in 3-D. We showed numerically and experimentally that using a thin and light line for the kite is key for a complete 3-D coverage over several square kilometres. We thus obtained a decimetre-resolution DEM covering 3.18 km2 with a mean error and standard deviation of the error of +7 and 22 cm respectively, hence achieving decimetre accuracy. With this data set, we showed that high-resolution topographic data permit both the detection and characterisation of an entire gully system with a high level of detail and an overall accuracy of 74 % compared to an independent field survey. Kite aerial photography with simple but appropriate equipment is hence an alternative tool that has been proven to be valuable for surveying gullies with sub-metric details in a square-kilometre-scale catchment. This case study suggests that access to high-resolution topographic data on these scales can be given to the community, which may help facilitate a better understanding of gullying processes within a broader spectrum of conditions.

- Article

(4933 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

Soil losses caused by erosion are a major hazard in agricultural areas. Management of this risk requires a good understanding of various erosion forms and the quantification of eroded volumes over areas of several square kilometres, which is the scale of the elementary watershed as defined by Jinze and Qingmei (1981). As noted by Van Westen (2013), topography is one of the major factors in most hazard analyses and the generation of DEMs plays a central role in their analysis. This is all the more true for gully erosion, considering that differencing DEMs theoretically allow for a direct estimation of eroded volumes. It is therefore appropriate to develop methods for generating detailed descriptions of landforms threatened by gully erosion at a limited cost. Cost-effective approaches are of great interest for monitoring on several spatial and temporal scales.

Before the advent of remotely piloted aircraft systems (RPASs), developments in remote sensing technology had already brought very high-resolution topographic data to the earth sciences community. Among these data, airborne lidar constituted a breakthrough, allowing for the characterisation of terrain surfaces with metre-size details. Such dense topographic data are of major importance for the description of hydrological-oriented geomorphological features (Vaze et al., 2010). These even allowed for the development of the first algorithms for automatic gully detection. Evans and Lindsay (2010) used a 2 m lidar DEM to detect gullies as zones with high curvature and low altitude relative to the average surrounding elevation computed within a moving window. With a lidar data set with a point density of 4 points m−2, Baruch and Filin (2011) performed curvature analyses to detect gully candidates in segments and then connect them to a complete network. Another example of curvature analysis is the work of Rengers and Tucker (2014), who identified gully headcuts from a 1 m lidar DEM as zones showing negative profile curvature below a given threshold and having a drainage area greater than 5000 m2. Höfle et al. (2013) proposed a method adapted to gullies of cushion peatlands using terrestrial lidar. In their work, gullies were delineated as polygons by detecting breaklines in the lidar DEM, and then artificial dams were manually positioned on the DEM, and finally, the formed sinks were filled. Occlusion effects due to the steep slopes of gully banks and the low-altitude point of view were noted by the authors. Most recently, Noto et al. (2017) used fuzzy logic on several topographic indices computed on a 1 m lidar DEM and combined it with image information and morphological operators to map gullies.

Although lidar technology has been developed for use aboard RPASs and has proven its potential in gully detection over large areas, this technology remains costly, which compromises its widespread use as an everyday monitoring tool. Structure from motion (SfM) and multi-view stereo (MVS) algorithms, which are recent developments in photogrammetry, represent new means of computing very high-resolution topographic data with a limited cost and have high potential in the geosciences as noted by Westoby et al. (2012) and Fonstad et al. (2013). In the specific field of gully erosion mapping and in line with lidar-based gully mapping approaches, Castillo et al. (2014) proposed an automated algorithm tested on three DEMs of different types and scales – SfM + MVS DEMs computed from ground and aerial images and a coarser and more classical DEM provided by the Spanish geographic institute – and demonstrated the potential of SfM + MVS DEMs for gully erosion studies. For interested readers, in-depth details on SfM and MVS algorithms and their use in the geosciences can be found in the reviews of Smith et al. (2016), Eltner et al. (2016), Mosbrucker et al. (2017) and Carrivick et al. (2016).

The advent of SfM and MVS in the geosciences has made it possible to implement cost-effective solutions that can take advantage of developments previously achieved with lidar data for landform mapping applications. Indeed, SfM-based methods can be deployed with consumer-grade cameras and even smartphones (e.g. Micheletti 2015). As image data acquisition is now possible with fewer constraints, the field of 3-D modelling has opened to a wide range of applications from worldwide modelling of cities and landscapes (Snavely et al., 2006, 2008) to the geosciences (Fonstad et al., 2013; Westoby et al., 2012). In combination with small-format RPASs, the potential of SFM and MVS algorithms for 3-D mapping is huge, as reviewed by Nex and Remondino (2014). However, covering several square kilometres with RPASs still requires costly fixed-wing or medium-format multi-rotor unmanned aircraft. Furthermore, the use of more affordable small-format rotary wing RPASs, which have shorter flight times, is limited in strong wind conditions. Finally, local regulations may hamper or even prohibit the use of autonomous aircraft in many places around the world. According to Colomina and Molina (2014), this is the main restriction on the widespread use of these powerful and versatile technologies.

For all these reasons, kites, which were used for more than a century for aerial image acquisition, have been enjoying renewed interest (Duffy and Anderson, 2016) for several years. In combination with most recent 3-D image processing algorithms, kites can hence be at the root of dependable and low-tech solutions, relying on the principles of so-called “frugal innovation”, which can simply be defined as “doing more with less” (Radjou and Prabhu, 2015). In various fields in the geosciences, kites have indeed already been used with photogrammetric techniques for applications requiring 3-D mapping. Oh and Green (2003) used kite imagery to compute a 3-D model of an urban area. Wundram and Loeffler (2008) compared a DEM computed from kite aerial imagery to a ground survey and classified vegetation in mountainous areas with favourable results. Smith et al. (2009) also demonstrated the potential of kite aerial photography for DEM production over small areas (i.e. less than 1 ha) using off-the-shelf cameras and professional photogrammetry software. More recently, 3-D modelling from kite imagery was carried out by a small number of authors with SfM + MVS software. Dandois and Ellis (2010) have compared this technique (called “Ecosynth” by the authors) to lidar data for deriving elevation data and canopy-height models. Bryson et al. (2013, 2016) performed centimetre 3-D mapping of vegetation in coastal areas and mapped coastal changes. Wigmore and Mark (2017) assessed the accuracy of SfM + MVS DEMs acquired with kites in comparison to lidar data in mountainous areas, where conditions limit the use of RPASs. More specifically, in the field of gully erosion, the potential of small-format cameras aboard kites and other platforms has been established by Marzolff and Poesen (2009) and Marzolff et al. (2011), who realised the 3-D monitoring of several individual gullies in southern Spain.

Yet there are no studies at the headwater catchment scale – i.e. over areas of several square kilometres – showing the use of kites for 3-D topography acquisition and gully erosion mapping. Indeed, kites suffer from several limitations, of which flight control is the most challenging, as noted by Verhoeven (2009a). Some authors have given instructions for ensuring proper data acquisition with kites: Bryson et al. (2013) used graduated lines to control flight altitude, and Aber et al. (2010) dedicated a chapter section to the principles and methods of kite aerial photography. However, the kite's ability to follow a predefined flight plan that enables 3-D coverage of several square kilometres has not yet been proven.

Thus, the aim of this study is to test the ability of low-tech kite aerial photography to obtain high-resolution DEMs that permit 3-D descriptions of active gullying in cultivated areas of several square kilometres. This goal jointly requires (i) the determination and assessment of the conditions that allow the use of a simple kite to acquire a suitable photogrammetric data set on a relatively large area and (ii) a 3-D map of gullies and assessment of the relevance of this map for erosion studies. To achieve this goal, we first expose and verify the conditions required to allow the use of a kite for photogrammetric acquisition over several square kilometres with numerical and field experiments. We then present a case study of image acquisition and processing on the Kamech catchment, located in northern Tunisia. Next, we propose a semi-automatic method for mapping gullies from the kite DEM. Finally we compared our results with independent ground surveys to assess the quality of the 3-D mapping of gullies and to exhibit the potential of kite DEMs with decimetre resolution and accuracy to study gully erosion.

2.1 Study site

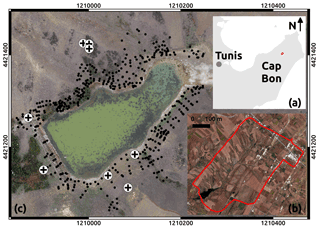

The study site is the Kamech catchment, located in Cap Bon, a peninsula in north-eastern Tunisia (Fig. 1a).

Figure 1Location of the Kamech test site and ground-truth data used in the SfM process. (a) Location of the Cap Bon peninsula, in north-eastern Tunisia; Kamech is marked in red. (b) Close-up of the Kamech catchment, 2.63 km2, delineated in red; its outlet is an artificial lake, visible in the south-east of the catchment. (c) Close-up of the available ground-truth data around the lake; scale is given by the external graduations (projection UTM, EPSG : 32632); the dam is the linear feature visible on the south-eastern side of the lake. The ground-truth data set is composed of ground control points (GCPs, crosses), which are used to give spatial references to the image data set, and validation points (black dots), which are used to independently validate the DEM computed from the image data set.

Kamech is one of the two catchments of the OMERE long-term hydro-meteorological research observatory (http://www.obs-omere.org, last access: 29 May 2018). A detailed description of the Kamech catchment can be found in Mekki (2003), Mekki et al. (2006) and Raclot and Albergel (2006). More than 70 % of the catchment area is ploughed and cultivated with rainfed crops. The climate is semi-arid to sub-humid with a mean interannual rainfall of 650 mm and a long dry summer season from May to October. The elevation ranges between 80 and 160 m. The slope can locally exceed 45∘. The substratum is mainly composed of marl and clay intercalated with sandstone layers. These layers have an average south-eastern dip of approximately 30∘ corresponding to the global anticline of Cape Bon. The right bank of the catchment shows a natural slope generally parallel to this dip and mainly presents marly layers. Hence, most gullies of the area have developed on this side. Sandstone outcrops are visible on the left bank of the catchment (Fig. 1b). The soils have a sandy-loam texture with depths ranging from zero to more than 2 m depending on the location within the catchment and local topography. The drainage network is composed of several kilometres of wadi and gully sections with decimetre to pluri-metre widths. The network drains intermittent flow discharge into a reservoir of 140 000 m3 built in 1994 that silts up at an annual rate of 15 t ha−1 because of water erosion (Inoubli et al., 2017). The gullies are permanent, and the gully heads are located at the edge of the agricultural fields. There is no significant ephemeral gully in the sense of Vandaele et al. (1996) or Nachtergaele and Poesen (1999).

2.2 Conditions for the use of a kite as a photogrammetric platform

To ensure photogrammetric image acquisition of several square kilometres, the method is based on the following hypothesis: with a very stable kite as a payload carrier, the position of the camera remains stationary relative to the kite operator. With this hypothesis, the flight path (i.e. the kite coordinates) is then a translation of the operator's course. Moreover, to use the simplest and most reliable apparatus, image acquisition is automatically triggered at a pre-set time interval. The flight plan can hence be prepared prior to the survey itself and followed on the ground without any need for remote control of the platform or a radio link between the camera and the operator. Thus, this hypothesis and the conditions ensuring its validity have to be carefully verified. This verification has been done with two complementary approaches, namely field observations and numerical simulations, which are described in the two following subsections.

2.2.1 Empirical kite flight characterisation

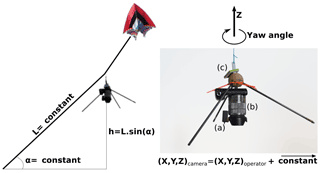

In this study, two delta kites were used, one with an area of 4 m2 and another with an area of 10 m2. We used framed delta kites chosen from a large variety of kites because of their flight qualities (stability and high flight angles), easy assembly – with no need for adjustment in the field – and a reasonable payload capacity. A schematic representation and a close view of the equipment used for this study are shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2Left: schematic principle of kite image acquisition with a steady flight angle. Right: payload close-up, which consists of a tripod with (a) an automatic trigger (b) a camera and (c) a GPS logger. The yaw angle is the angle of the camera around the z axis.

As shown, the camera was mounted under a protective tripod hanging from a long line forming a simple pendulum. This long pendulum smoothed out the potentially erratic movements of the kite. Finally, acting as a vane in the wind, the tripod allowed for natural aerodynamic stabilisation of the yaw angle, which is the rotation angle around the vertical axis of the tripod (Fig. 2c). The line used for all experimental set-ups was Cousin-Trestec TopLine Ultimate 16175, which is made of Dyneema®, a strong and light material. This line had a strength of 87 daN, a diameter of 0.8 mm and a linear mass density of 0.39 g m−1. The two delta kites performed a total of five flights, with wind conditions ranging from Beaufort 3 to Beaufort 7 and with line lengths ranging from 150 to 700 m. The use of the Beaufort scale was preferred in the field because it can be estimated from direct observation of land conditions (moving branches, raised dust, etc.) and does not require an anemometer. Camera and operator positions were simultaneously logged with a standalone QSTARZ BT1400S GPS data logger used with a 1 Hz acquisition rate (Fig. 2c). This data logger had a given accuracy of 3 m. These logs were used to compute effective kite flight angles from the pairs of camera and operator positions. Analysis of these flight angles was performed to verify the validity of our hypothesis and to empirically estimate the actual average flight angles. This information also made it possible to check the wind range in which the wing remained stable with a steady flight angle and with neither shocks nor sudden movements during the flight.

2.2.2 Simulations of kite flights

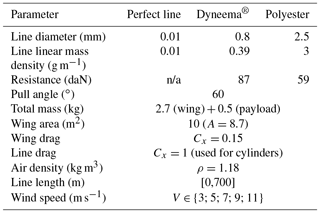

In addition to collecting the experimental data, numerical simulations of line shape and kite position were performed for different wind conditions (from 3 m s−1 to 11 m s−1 in increments of 2 m s−1) and for different line lengths (from 0 to 700 m). The materials used for kite lines are of particular interest. Highly resistant lines such as Dyneema® can be used in much smaller diameters than polyester of comparable strength, which results in less weight and aerodynamic drag. Polyester, Dyneema® and a perfect theoretical material with negligible mass and diameter were numerically compared to each other. For all the simulations, the rig load was 500 g, which is the actual mass of the rig we used (shown in Fig. 2). Simulations were performed with the physical characteristics of the 10 m2 delta wing, which has a mass of 2.7 kg.

The model used was an ad hoc finite element model written in MATLAB. The line was sampled in sections of 1 m. The aerodynamics of the line were taken into account with the equation , where F is the drag force in N, A is the projected surface area in m2, ρ is the air bulk density in kg m−3, V is the wind speed in m s−1, and Cx is the dimensionless drag coefficient. This equation was also used to calculate the wind forces on the kite as a function of wind strength. All the parameters used for the simulations are reported in Table 1. These numerical simulations aimed to assess the impact of the kite line characteristics on the aforementioned hypothesis.

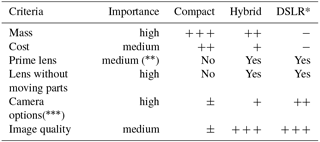

2.3 Photogrammetric acquisition

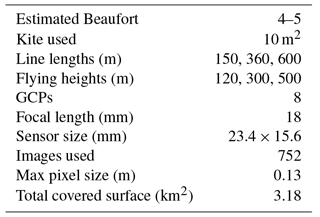

Image acquisition was performed in September 2013 after the dry season, when vegetation cover was minimal. The equipment used for photogrammetric acquisition is shown in Fig. 2 above. The Dyneema® kite line was graduated every 10 m for the first 100 m and then every 50 m with a simple colour/thickness coding system with a comparable approach to that used by Bryson et al. (2013). Image acquisition was performed with the 10 m2 kite. A maximum flight altitude of 500 m was chosen to acquire images with decimetre ground sampling distance. The corresponding line length was estimated with the worst case for the flying angle (50∘) and resulted in a maximum line length of 600 m. The targeted area was covered with parallel flight lines. These lines were oriented north-east to south-west along the global orientation of the catchment. The corresponding ground path was walked from the right bank towards the left bank. To simplify the field work, the operator remained at first on the same path near the right bank crest and unrolled different line lengths (150, 360 and then 600 m) so that the kite was positioned at the right downwind distance from the operator. Then, the operator continued to walk the rest of the ground path towards the right bank and covered the targeted area as planned. Images were taken with a Sony NEX-5N camera (Fig. 2b), which has a 16 Mpix 23.4 × 15.6 mm sensor. This camera was used with a fixed 18 mm focal length, and the image stabiliser was disabled, which are two important settings for the lens auto-calibration step in SfM processing. This camera was chosen as the best compromise at the time of the experiment between mass, suitability for photogrammetric analysis and cost (see Table B1 in the Appendix). Automatic triggering was performed with a gentLED-Auto 05C intervalometer (Fig. 2a). A time interval of 5 s between each image was chosen to ensure sufficient overlap.

Complete coverage of the targeted area in the Kamech catchment was achieved within two flights of 3 h each. A total of 752 images were used to cover an area of 3.18 km2. The maximum flight altitude of 500 m led to a maximum estimated ground pixel size of 0.13 m (see Table 2 for a summary of all these data). The upstream part of the catchment being crossed by a power line, we avoided having the kite line near it for safety reasons. As a result, a small area of the catchment was not covered by multi-view imagery. However, more of the area downstream and outside the catchment was reached. As a result, the data set covered an area of 3.18 km2, which exceeded the area of the catchment itself (2.63 km2).

Finally, eight points (cross marks on Fig. 1c) that were clearly visible in the kite images were used as GCPs. Their position was measured with a Topcon GR-3 RTK DGPS with a theoretical altimetric and planimetric accuracy of 1.5 cm. These GCPs were used as a spatial reference in the photogrammetric processing.

2.4 DEM computation

Kite images were processed with MicMac open-source software (Pierrot-Deseilligny and Paparoditis, 2006). This software implements both a bundle block adjustment and a hierarchical, true multi-view dense matching algorithm that is also used by the French Institut Géographique National to produce 3-D cartography. MicMac hierarchically computes multi-view dense matching from coarse grids to the full resolution by gradually refining the results at successive scales. The full resolution of the DEM is the average ground resolution of the images, which is estimated from the average flying height. This average flying height itself is estimated from the mean flight altitude and the average altitude of key points computed with the SIFT algorithm (Lowe, 2004). All images covering the same point of interest are taken into account in the same bundle adjustment for the calculation of each point in the DEM. This procedure results in an altimetric precision of 1 pixel on average. The MicMac process is typical of SfM + MVS algorithms (see Appendix) and is comparable with them (see for instance Stumpf et al., 2015 and Jaud et al., 2016).

The SfM step (i.e. SIFT point recognition and matching plus bundle calibration) is completely automatic and followed by two manual steps. First, the area for dense image matching was selected. Second, the GCP positions were manually digitised in the images to give the project a cartographic reference. The automatic MVS dense image matching was finally run and resulted in a 0.20 m DEM. All image processing was performed on a laptop computer with an Intel Core i7-3840QM CPU at 2.80 GHz and 32 GB of RAM.

2.5 Gully detection

Similarly to Castillo et al. (2014), a gully is considered in this study to be a morphological object with a marked depression that is in the immediate proximity of a channel, the latter being determined by another algorithm. To delimit depressions, most recent studies use sliding windows. For example, Castillo et al. (2014) use a sliding “normalised elevation” kernel. We chose another approach: we convolved the DEM with a Gaussian kernel by computing the inverse Fourier transform of the pointwise product of the Fourier transforms of the DEM and the Gaussian kernel. This method has two advantages. The first relates to computation time: with the Fourier transforms, the algorithm has a computational complexity of O(n log(n)), with n being the total number of pixels of the DEM. Sliding window algorithms have a computational complexity of O(n.m), with m being the window size in pixels. Hence, convolution with Fourier transforms is faster than filtering with sliding windows, except for very small windows. Above all, the processing time with convolution is independent of the kernel size. The second advantage is as follows: convolution by a Gaussian kernel simulates diffusive processes. Hence the DEM after convolution represents the hypothetical future shape of the ground surface after the processes involved in linear erosion have stopped and the processes leading to the healing of the gullies have begun.

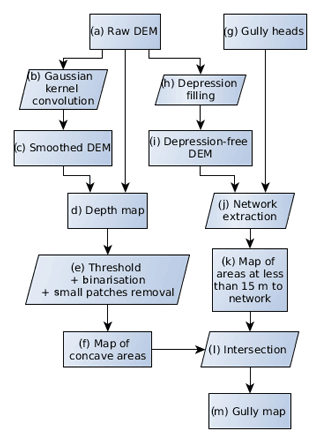

For the delimitation of the channel network, the fully automated algorithm proposed by Passalacqua et al. (2010) was tested at first (results not reported here). With this algorithm, the automated localisation of gully heads detected by high positive plan curvatures presented flaws. We observed that different threshold values – including the proposed default value – resulted either in an excessive number of missing gully heads or in categorising many anthropogenic depressions as gully heads, such as village streets or spaces between trees in orchards. As noted by Orlandini et al. (2011), the automatic detection of channel heads is indeed most problematic for small-scale features such as some of those targeted by our work. Thus, gully heads were digitised from a shaded view of the DEM with the same type of expertise as one would use in the field. This approach was used by Höfle et al. (2013) to produce their validation data set. The entire digitisation of the gully heads on the DEM was achieved within less than 2 h. Once the gully heads were digitised, the algorithm followed the flow chart in Fig. 3.

Figure 3Flow chart of the method used to map gullies from the kite DEM. The letters associated with each step are referenced in the text describing the method in Sect. 2.5

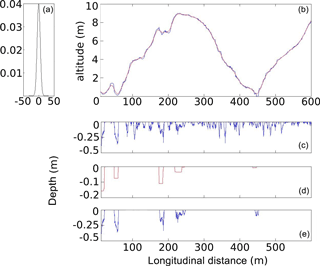

The raw DEM (Fig. 3a) was convoluted with a Gaussian kernel (b) of a standard deviation of 10 m, which resulted in the smoothed DEM (c). We chose this value so that twice the standard deviation of the kernel was equal to the width of the largest gullies to be detected (i.e. 20 m). The raw DEM (a) was subtracted from the smoothed DEM (c) to create a depth map (d), which was therefore the estimated depth of the natural surface below the smoothed surface. Step (e) consisted of applying a threshold to the depth map and cleaning the result up. The threshold was chosen as slightly larger than the pixel size considering that lower differences in elevation would probably be noise. Features that did not show depths greater than 25 cm were hence discarded. The cleaning consisted of pruning out patches with volumes less than 1 m3. This value allowed us to eliminate small-scale noise while keeping each detail of the gullies, even when they were made of discontinuous patches. Step (e) resulted in the (f) map. Steps (a) to (f) are illustrated with a section view in Fig. 4.

Figure 4Principle of gully detection: (1) a Gaussian kernel with a 10 m standard deviation; (2) original (blue) and smoothed (red) topography; (3) raw negative differences between the original and smoothed topography; (4) detection of the potential gullies, then pruning out elements of less than 1 m3; and (5) profiles of the detected gullies.

Steps (g) to (k) correspond to the extraction of the hydrological network. To map the hydrological network downstream of the previously digitised gully heads (g), a depression-free DEM (i) was generated from the raw DEM by filling gaps (h). The hydrological network (j) was generated by a steepest descent algorithm in (i) from gully heads (g). Considering the typical width of the gullies at the test site, a binary map (k) of the areas located less than 15 m from the network was computed. Intersecting the binary maps (f) and (k) resulted in the final gully map (m).

2.6 Validation

2.6.1 DEM quality

The kite DEM quality was evaluated on an independent validation data set composed of 469 points (see Fig. 1c for their localisation) and the median error, mean error and standard deviation of error were used as evaluation criteria. This control data set was surveyed with the same Topcon GR-3 RTK DGPS used for GCPs. These data came from a recurrent operation of bathymetry and topography of the reservoir performed a few weeks before image acquisition and from which points covered by vegetation were excluded. A qualitative assessment was also performed with a visual inspection of the kite DEM at full resolution.

2.6.2 Gully map

The quality of the gully map derived from the kite DEM was also assessed with independent data. The gully map was compared to a gully network derived from a field survey and completed by the interpretation of a QuickBird image. The field survey was carried out between 2009 and 2012 on nearly 70 % of the total gully and wadi network length of the Kamech catchment (Ben Slimane, 2013). Each gully and wadi was divided into sections whenever a branching (confluence) or significant change in the cross-section size was identified. For each gully upstream, middle and downstream positions were recorded with a handheld Garmin eTrex GPS. The precise delineation of each section was photo-interpreted on the orthorectified pan-sharpened QuickBird image using the upstream, middle and downstream GPS positions of the surveyed sections. Gully sections that were not described during the field survey were delineated on the orthorectified pan-sharpened QuickBird image only.

As in Thommeret et al. (2010), the field-mapped network was considered as a reference and two parameters were computed from the match: “the false negative (underdetection), which is the length of the reference not included in the extracted network domain, and the false positive (overdetection), which is the length of the extracted network not included in the reference domain.” We also added a parameter that aimed to represent the overall accuracy and that was computed as the ratio of the total length of correctly mapped gullies to the total length of surveyed gullies.

2.6.3 Gully 3-D morphology

Finally, we tested the ability of the DEM to derive 3-D information that allows for gully morphology monitoring. This evaluation was based on a profile comparison of the kite DEM with a reference DEM derived from an intensive field topographic survey of a mid-size gully. This reference DEM was calculated on a 0.05 by 0.05 m grid from a very dense point data set acquired in 2009 using a total station that had an () accuracy better than 0.01 m (Khalili et al., 2013). Standard statistics on the deviation between the kite DEM and the reference DEM were derived on an elevation profile of a path composed of a series of line segments.

3.1 Simulated line characteristics

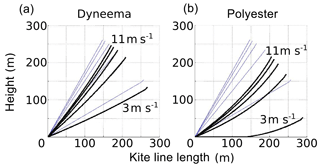

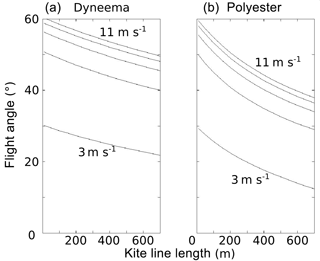

Figure 5 shows the results of kite line shape simulations with different wind speeds, line characteristics and physical processes taken into account.

Figure 5Comparison of the shapes on the 300 m lines (black bold) with perfect ones (thin grey) on a kite flown under different wind conditions and with different line materials. Simulations were performed at five wind speeds from 3 to 11 m s−1 in steps of 2 m s−1. The load of the rig (Fig. 2 – right) for the simulation is 500 g. Perfect lines (thin grey) were modelled with negligible weight and drag. (a) Dyneema® line (0.39 g m−1). (b) Polyester line (3 g m−1).

This figure revealed the following three findings: (i) with light and thin lines, the kite line is almost straight, and the flying angle is maximal; (ii) when the kite is flown in sufficiently strong wind, wind speed variations cause only small effective flight angle variations; and (iii) the latter observation is all the more true when the kite line is thin and light. These conclusions corroborate the field observations, which made us choose a thin and light line for photogrammetric acquisitions. Using a thin and light kite line – and a kite adapted to the actual wind conditions at the time of image acquisition – is hence a key condition for obtaining a steady flight angle and the required stable position of the kite relative to the operator.

Figure 6 shows the simulated flight angle as a function of the line length for the Dyneema® line and polyester line.

Figure 6Simulation of the variation in flight angle with the line length for different winds and line materials. Simulations were performed with five wind speeds from 3 to 11 m s−1 in steps of 2 m s−1. (a) Dyneema® line. (b) Polyester line.

For both cases, the simulations showed that the flight angle dropped with increasing line length. The drop was slight for the Dyneema® but critical for the polyester line due to the stronger “banana shape” of the line observed in Fig. 5. Hence, the use of thin and light kite lines such as Dyneema® lines allows for kite flights with a steady flight angle at a given line length (Fig. 5) but also with various line lengths (Fig. 6). This steady flight angle makes the line length the only factor influencing the variation in the kite position relative to the operator. As a consequence, kite flights can effectively be planned and then properly realised. However, it is recommended to use a margin of security, considering the slight drop in flight angle for greatest line lengths. These findings were confirmed by the field experiments presented in the following section.

3.2 Observed kite flight angles

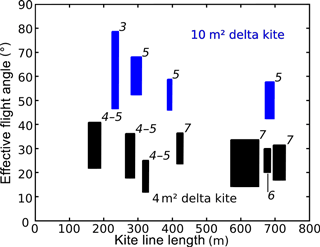

Figure 7 shows the measured effective flight angles for the two kites used with the Dyneema® line for different line lengths and different wind conditions.

Figure 7Observed flight angles for the two kites and various wind speed conditions and line lengths. Wind conditions (in italics) are expressed in the Beaufort scale. Measured flight angles were grouped in min/max boxes for each flight. Blue boxes represent the behaviour of the 10 m2 kite and black boxes represent the behaviour of the 4 m2 kite.

This figure corroborates the simulation results shown in Fig. 6: during field experiments, the flight angle dropped slightly but significantly with line length. This drop must hence be taken into account in preparation for image acquisition. We also noted that the smaller kite – which has a tail – flew at a significantly lower angle than the larger one. These experiments also included a flight (the leftmost blue box in Fig. 7) with insufficient wind strength to fly the 10 m2 kite, which resulted in a wider range of flight angles and greater variability in the camera position relative to the operator. This result confirms that even with a thin and light line, the kite must fly within the appropriate wind conditions so that the flight angle remains steady.

3.3 DEM quality

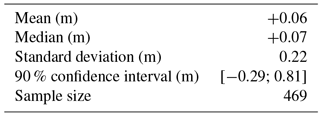

The quantitative assessment of the DEM quality is reported in Table 3.

The error statistics demonstrated good agreement between the kite DEM and the independent DGPS-surveyed validation data set. In particular, the mean error and median error were smaller than the pixel size and the standard deviation of the error was of the order of the pixel size. These figures show that the DEM acquired by kite constitutes a reliable model of the catchment topography.

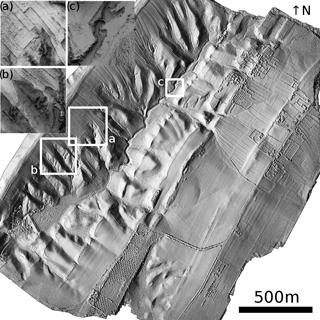

Moreover, a qualitative assessment of the kite DEM was carried out with a manual inspection of full-resolution DEM shaded views with three close-ups (Fig. 8). The assessment showed that the kite DEM planimetric and altimetric resolutions allow for the visual detection of numerous landscape features, including most man-made structures (roads, tracks, buildings) and gully heads that were identified in the field (e.g. Fig. 8a and b). The plot locations and limits were also clearly depicted (Fig. 8a). Indeed, the boundaries between two separate adjacent plots are not exposed to tillage erosion and finally form small humps that are visible in the DEM. In the main thalweg (Fig. 8c), marks of regressive erosion were visible, and headcut locations could easily be identified. The potential of the kite DEM for use in extensive gully mapping within an area of several square kilometres is quantitatively evaluated in the next section.

Figure 8Shaded images of the computed DEM over the Kamech test site. The main image is a classical shading of the DEM computed with a unique illumination source located in the east. The three zoomed-in panels are shaded images computed as the portion of visible sky at each point. This latter type of shading highlights local features such as steep slopes and areas of high curvature: (a) shows some cultivated plots with the plot borders easily visible and a gully head downstream of the plots; (b) shows a gully head; and (c) shows the main thalweg headcut, which is experiencing slow regressive erosion processes.

3.4 Assessment of 3-D gully modelling

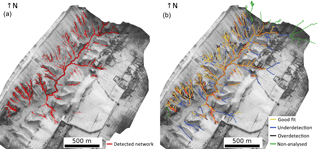

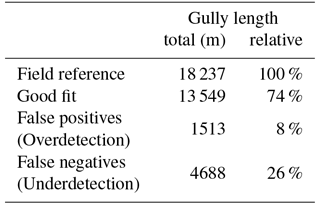

An assessment of the gully network delineation was conducted at the scale of the whole channel network, and the 3-D restitution of the internal morphology of a gully was assessed at the scale of a single gully. Figure 9 shows the final gully map obtained by the proposed method superimposed on the shaded DEM and a map of the validation results. Statistics of the comparison between the network extracted from the DEM and the field reference network are presented in Table 4.

Figure 9Results of the gully mapping algorithm. (a) The gully network identified from the kite DEM is represented in red and superimposed on the shaded DEM. (b) Comparison with ground survey: yellow lines represent the part of the network correctly detected by our algorithm; black thick lines represent gullies detected by our algorithm where no gully was surveyed in the field (overdetection); blue lines represent gullies that were identified on the ground but not detected by our algorithm (underdetection); green lines represent gullies that were identified on ground but not used for error statistics, because they were outside the Kamech catchment area or their heads were outside of the area covered by the kite DEM.

Table 4Error statistics of the comparison at the scale of the channel network (Fig. 9).

The analysis of the gully map and the statistics showed a very good agreement between the detected gullies and the field reference. The overall accuracy was 74 %, with 8 % overdetection and 26 % of the network length unmapped. An inspection of the comparison map showed that most gullies that were not detected by our algorithm were located on the left bank (i.e. the south-eastern half), where gullies are less incised than those located on the right bank. Furthermore, most overdetections (gullies found by our algorithm but not surveyed on the ground) consisted of small gully segments mainly located on the right bank of the catchment.

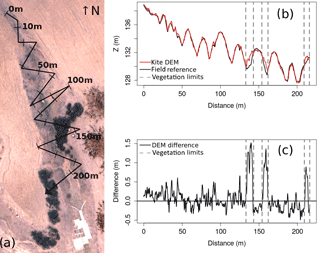

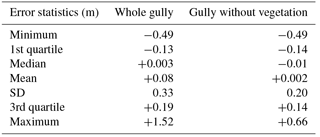

Next, validation of the 3-D gully map was performed at the local scale and at very high resolution. Figure 10 shows a 3-D comparison between a gully modelled by the kite DEM and dense measurements from a total station survey.

Figure 10Comparison of the kite DEM with the ground survey. (a) Plan of the gully showing a gauging station at the gully outlet (white), two dense shrub patches of approximately 1 m height on the sides of the gully (dark black) and three patches of recent manure application (brown) in the field on the left bank of the gully; the graduated black line shows where profiles have been extracted. (b) Comparison of kite DEM (red) and ground survey (black) profiles; the vertical dashed lines delimit areas covered with shrubs. (c) Difference between the kite DEM and the ground survey along the same profile. Error statistics computed on this area are reported in Table 5.

Comparison of the profiles extracted from the kite DEM and from the surveyed DEM showed good agreement along the whole profile, except for areas covered by vegetation. The influence of vegetation was clearly detected (Fig. 10c), with elevation differences significantly differing from the surrounding noise. These observations were supported by the associated error statistics (Table 5), with a mean error of +0.08 m, which decreases to +0.002 m when not taking into account zones covered by vegetation (parts of the profiles surrounded by vertical dashed lines in Fig. 10b and 10c). These results indicate that the kite DEM constitutes a reliable source of topographic data for the description of gully erosion forms. These findings seem likely to be extended for other gullies considering the good accordance between error statistics shown in Tables 5 and 3.

Table 5Error statistics at the scale of the gully shown in Fig. 10.

Moreover, a comparison of the quartiles estimated from the whole gully and from the non-vegetated part of the gully showed that vegetation mainly resulted in larger positive extrema, whereas the first, second and third quartiles remained comparable. The results at this scale were very similar to those computed with the 469 ground points sampled near the lake (Table 3 above), with a standard deviation of the error for the DEM statistics being closer to that for the non-vegetated case. This result may indicate that vegetation is more likely to result in local errors rather than in a global deviation.

In this study, we comprehensively assessed a cost-effective workflow to map gullies at the scale of the elementary watershed from images acquired by kite. Several important considerations have emerged. These considerations refer to the image acquisition step, the quality of the kite DEM and the accuracy of the gully map.

4.1 Large photogrammetric data sets with kites

Our study showed that achieving coverage of several square kilometres with decimetre resolution and accuracy was possible with basic equipment for the acquisition of a photogrammetric data set. These results represent an improvement over those presented in El Maaoui et al. (2015), where the same acquisition method was also used successfully over an area of only one-tenth of that covered in this study. In other works that obtained DEMs with kites, the maximum areas covered were also of the order of several hectares (Wundram and Loeffler, 2008; Marzolff and Poesen, 2009; Smith et al., 2009; Bryson et al., 2013, 2016; Currier, 2015). Our results clearly constitute an extension of the kite's capability. In particular, our work presents novel findings on the conditions that must be met to make kite photogrammetric acquisition successful at this scale. A correct realisation of a planned flight is hence a critical issue for tethered platforms, as has been noted by others (Verhoeven, 2009a; Murray et al., 2013). Numerical and field experiments have revealed that the choice of kite line was a key factor in the success of our workflow. To the best of our knowledge, the importance of the kite line for a proper photogrammetric acquisition has rarely been considered with both numerical and field experiments in previous works. Verhoeven et al. (2009b) stressed out the importance of a thin and light line on the basis of personal and external (e.g. Bults, 1998) empirical observations and advised the use of Dyneema® to mitigate line sag. Our study hence corroborated previous empirical observations and provided new insights on the importance of the kite line, with original numerical experiments.

If kites are proven to be valuable platforms for photogrammetric acquisition, they have some limitations. The two main limitations are (i) the fact that the line must be clear of obstacles and (ii) the need for a minimal wind speed. We faced the first issue in the most upstream part of the catchment because of a power line. Obstacles can also be found in densely vegetated or densely urbanised areas. Cases of obstruction have also been discussed by Verhoeven (2009a), who concluded that not every place is suitable for performing image acquisition from tethered platforms. The second issue, also noted by Bryson et al. (2013), can be approached as in Vericat et al. (2009), who used a kite to which a small helium blimp was added. Marzolff and Poesen (2009) used kites and balloons in alternation. In our opinion, in most cases, when the use of RPASs is not hampered by local regulations, kites associated with small-format multi-rotor RPASs represent a relevant all-weather solution. Indeed, the great advantage of small RPAS systems, in addition to being fairly inexpensive platforms, is the fact that they can provide very high-resolution spatio-temporal data with reduced response times in varied conditions (Nex and Remondino, 2014). However, typical small-format RPASs may remain grounded during windy periods, thus preventing the requested rapid response. The other main niche for kites is related to local regulations, either for the flight itself or due to regulations regarding crossing borders with the equipment.

On another note, kites can fly for hours when weather conditions are appropriate. This autonomy represents a completely different paradigm to that for most RPASs. With the equipment presented above, the overall autonomy was only limited by the internal power supply of the camera. Within a single flight of 3 h, several thousand overlapping images can be acquired. This figure gives an idea of the mapping potential of this method, which produces DEMs in the gigapixel range.

4.2 DEM quality

Beyond the ability to acquire 3-D data over several square kilometres with kites, our aim was to demonstrate that these topographic data were reliable. We showed that the estimated altimetric bias was lower than the pixel size and that the estimated deviations were in the order of magnitude of pixel size. In other words, validation with an independent ground survey showed that the produced DEM had a decimetre resolution and accuracy.

Few works using kites have assessed the DEM elevation error. Our results compare quite well with these works. Wundram and Loeffler (2008) achieved a +0.13 m mean error, 0.36 m standard deviation of the error and 0.75 m maximal error on a 0.25 m resolution DEM (one thousand validation points). Smith et al. (2009) acquired images with an estimated 0.01–0.02 m ground sampling distance. The authors obtained a −0.01 m mean error and 0.065 m standard deviation error estimated with 399 independent validation points. Verhoeven et al. (2012) acquired images with a 0.03–0.08 m ground sampling distance and computed a 0.04 m resolution DEM of a test site of roughly 10 ha. They estimated x, y and z errors with 61 independent validation points and found a mean error of 0.04 m and RMSE of 0.16 m on the altitudes. El Maaoui et al. (2015) computed a DEM with a ground sampling distance of 0.06 m. A quality check with 176 independent validation points resulted in a mean error of +0.04 m and a standard deviation of 0.07 m. Finally, with 0.004 m resolution images acquired on a 50 by 150 m area and a final DEM ground sampling distance of 0.05, Bryson et al. (2016) estimated the mean error at −0.019 m and the standard deviation at 0.055 m with 86 validation points. Our work confirmed that the range of kites can be extended to several square kilometres with decimetre resolution while maintaining the accuracy in the pixel size range.

4.3 Gully network map and 3-D gully morphology

Although the overall accuracy of 74 % proved that our method was effective, the very process of validating the gully maps obtained from high-resolution DEM processing raises issues. To begin, validation methods are quite varied in the literature. Most authors (Evans and Lindsay, 2010; Baruch and Filin, 2011; Höfle et al., 2013; Castillo et al., 2014) have used manual digitisation of the gullies on the DEM as validation data and focused on different gully characteristics: width and depth (Evans and Lindsay, 2010), visual comparison (Baruch and Filin, 2011; Höfle et al., 2013), and areal and volume difference (Höfle et al., 2013; Castillo et al., 2014). Some authors (e.g. Noto et al., 2017) did not even validate the gully mapping results. Infrequently, studies such as Thommeret et al. (2010) have used field surveys as validation data for gullies that were automatically mapped from a DEM. Similarly to their study, our validation data were in the form of a channel network, and we used the same indicators as they did. We obtained a false positive rate (overdetection) of 8 % and a false negative rate (underdetection) of 26 %. Our results compare favourably to those of Thommeret et al. (2010), who had false positive rates ranging from 5 to 16 % and false negative rates ranging from 29 to 55 %. Moreover, our results follow the same tendency, with false negatives rates being higher than false positives. This result may be explained by the fact that all gully mapping algorithms, including the one presented here, are based on the morphological characteristics of gullies (i.e. what a gully is) but do not benefit from characteristics that are known not to be shown by gullies (i.e. what a gully is not). In our opinion, this approach would be especially useful for avoiding confusion between gullies and man-made structures, which may be among the most delicate features to handle. This confusion may indeed explain some of the remaining inaccuracies we observed, and more generally, these issues have also been faced by others (Castillo et al., 2014).

The detection of gullies in DEMs faces the difficulty of determining an unambiguous and generic definition of what a gully is. Castillo et al. (2014) indicated that to their knowledge, no one has yet assessed where gullies “begin” in the transverse direction. Conversely, Evans and Lindsay (2010) stated that “gully edges are the critical features for gully mapping”. Baruch and Filin (2011) noted that the assumptions usually used in channel-like extraction techniques do not apply to the environment of alluvial fans in which they propose an ad hoc gully mapping method. In brief, due to the variety of gully shapes and the fuzzy definition of their extent, each gully mapping algorithm in the literature so far requires the manual tuning of parameters and/or thresholds and is preferably applied to specific landscape types.

A possible workaround would be the use of multi-scale analysis, which was still seen by Passalacqua et al. (2015) as a future research direction for high-resolution topography analysis. For future work in this direction, our algorithm has the advantage of being based on Fourier transforms instead of sliding windows, which makes the computation time independent of the characteristic size of the kernel and hence opens the door to multi-scale filtering with controlled computation times. Computing time is indeed one issue for DEM processing: for instance Castillo et al. (2014) have been unable to process the full resolution of their largest DEM. Considering that upcoming topographic data sets will probably be more extensive and will have higher resolutions, this may still be an issue that will have to be mitigated by algorithmic improvements such as the one we have proposed.

The interest in multi-scale approaches is as strong as the 3-D information of such DEMs is rich, which is the case for the data obtained in our study. The comparison of dense elevation profiles between the kite DEM and ground reference hence showed good agreement. These findings thus confirmed, at a very local scale, the results on DEM accuracy found at the scale of the whole DEM. However, this detailed analysis raised the issue of vegetation cover. This issue is present in several classical cases where image-based approaches have limits that lidar does not have. However, with big image data sets, SfM + MVS DEMs can reach densities that are comparable to or even exceed those of aerial lidar point clouds. This property would allow for the development of vegetation filtering algorithms tailored to these dense and multi-view image data. Second, our results can be compared to the work of Marzolff and Poesen (2009), who used kites and balloons with a focus on two gullies. They determined that gully morphology and even gully changes could be assessed. In our case, with comparable sensibility and data available at the scale of the whole catchment, this morphological information would enable the description of different processes that occurred in different gullies or even at different times in the same gully, such as renewed erosion in older gully systems. Further work may then repeat our experiments to monitor ongoing gully erosion processes. These experiments would indeed be of great help, for instance, in understanding the source of the sediments responsible for reservoir siltation.

This paper proposes a complete workflow, from image acquisition with kites to a final gully map at the scale of a kilometre-square catchment with a careful assessment of each step. For image acquisition, we found that a key factor was the use of a thin and light line, which results in steady kite flight angles and thus a proper realisation of a kite photogrammetric flight in such large areas. Then, we showed that low-tech kite aerial photography could be successfully used for the acquisition of a high-resolution DEM covering more than three square kilometres with decimetre resolution and accuracy. Finally, we demonstrated that an appropriate gully mapping algorithm developed and applied to this DEM proved to be appropriate for the characterisation of gullies with 3-D decimetre details. Correct matches were obtained for 74 % of the gully lengths at the scale of an entire channel network. Still, kites require minimal wind speeds. This technique may therefore be thought of as a tool to be used in conjunction with small-format RPASs, especially when the latter cannot fly because of technical or administrative obstacles. Then, the proposed gully mapping method requires the intervention of an operator for the digitisation of gully heads. This approach may not be adapted to contexts with an excessive number of individual channels but proved appropriate in pruning the false positives produced by automatic procedures on anthropogenic features. Nevertheless, our study demonstrated that kite aerial photography using simple but appropriate equipment and an appropriate gully mapping algorithm represents a valuable tool for accurately surveying several hundred gullies at the scale of a kilometre-square watershed with decimetre detail, which may compare favourably with most ground surveys at these scales. These findings suggest that kites, SfM + MVS, and adequate gully mapping algorithms provide greater access to high-resolution topographic data of kilometre-square watersheds and will facilitate a better understanding of gullying processes in a broader spectrum of conditions.

Image data and digital elevation model can be shared for collaboration purposes upon request by contacting the corresponding author.

Description of the commands used sequentially in the typical MicMac pipeline, from images to DEMs and orthophotographs:

-

Tapioca: SIFT points are computed and matched; image resampling ratio affects the number of SIFT points.

-

Tapas: image orientation and auto-calibration takes place; memory requirements grow with the number of SIFT points and images and can be prohibitive; there are possible workarounds with RedTieP/OriRedTieP.

-

Tarama: a first raw mosaic of the area is computed; it can be used to obtain a quick estimate of the covered area.

-

SaisieMasq: the area of interest is manually delimited.

-

SaisieAppuis: GCP positions in images are manually measured.

-

GCPBascule: the model is georeferenced.

-

Malt: dense image matching occurs; the final DEM resampling ratio and regularisation parameters can be adjusted.

-

Tawny: orthophotograph mosaicking is completed.

Table B1Advantages and drawbacks of three different camera technologies for acquisition with a kite for photogrammetry. The two first criteria are specific to kite-borne photogrammetry, while the last criteria are more general and apply to any photogrammetric application.

* Digital single-lens reflex camera. A lens with the zoom ring scotch-tapped on is a decent workaround if no prime lens is available. Includes the possibility of switching off the autofocus and the image stabiliser, both of which make auto-calibration difficult.

It is worth noting that flying large kites, especially in strong winds, can raise security issues. Aside from Aber et al. (2010) and Verhoeven et al. (2009b), this information is still barely reported in the scientific literature. The problems we faced appeared only under conditions of strong winds. These problems include small burns on hands, arms or clothes when the line is moving too fast or when the winder is temporarily out of control during a wind gust. This problem may also occur when the kite shows erratic movement in strongest winds when the operator is walking upwind. To avoid such problems, the following safety measures can be adopted: (i) ensuring physical protection of the operator with leather gloves, covering clothes and ensuring the safety of other people by keeping the downwind zone free of any lightweight and large equipment; (ii) keeping in mind that danger – and necessary expertise – grows with wind strength, a clever decision may be not to fly if conditions are not met; (iii) securing the flying gear (attaching it with hooks, for instance); and (iv) paying attention to equipment and people.

The authors declare no competing interests.

This article is part of the special issue “The use of remotely piloted aircraft systems (RPASs) in monitoring applications and management of natural hazards”. It is not associated with a conference.

The OMERE observatory (http://www.obs-omere.org, last access: 29 May 2018), funded by the French

institutes INRA and IRD and coordinated by INAT Tunis, INRGREF Tunis, UMR

Hydrosciences Montpellier and UMR LISAH Montpellier, is acknowledged for

providing a portion of the data used in this study. In particular, we

gratefully acknowledge Kilani Ben Hazzez M'Hamdi, Radhouane Hamdi and Michael

Schibler from IRD Tunis for the work that was carried out in the field to obtain topographic

data. This research was also supported by the TOSCA-CNES project “A-MUSE;

Analyse MUlti-temporelle de données SENTINEL 2 et 1 pour le monitoring de

caractéristiques observables de la surface du sol, en lien avec

l'infiltrabilité”(2018–2019).

Edited by: Daniele Giordan

Reviewed by: Mitchell Bryson and four anonymous referees

Aber, J. S., Marzolff, I., and Ries, J.: Small-format aerial photography: Principles, techniques and geoscience applications, Elsevier, 2010. a, b

Baruch, A. and Filin, S.: Detection of gullies in roughly textured terrain using airborne laser scanning data, ISPRS J. Photogramm., 66, 564–578, 2011. a, b, c, d

Ben Slimane, A.: Rôle de l'érosion ravinaire dans l'envasement des retenues collinaires dans la Dorsale tunisienne et le Cap Bon, Phd thesis, Montpellier SupAgro & INAT, 2013. a

Bryson, M., Duce, S., Harris, D., Webster, J. M., Thompson, A., Vila-Concejo, A., and Williams, S. B.: Geomorphic changes of a coral shingle cay measured using Kite Aerial Photography, Geomorphology, 270, 1–8, 2016. a, b, c

Bryson, M., Johnson-Roberson, M., Murphy, R. J., and Bongiorno, D.: Kite aerial photography for low-cost, ultra-high spatial resolution multi-spectral mapping of intertidal landscapes, PLOS ONE, 8, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0073550, 2013. a, b, c, d, e

Bults, P.: What's my line?, The Aerial Eye, 4, 6–7, 1998. a

Carrivick, J. L., Smith, M. W., and Quincey, D. J.: Structure from Motion in the Geosciences, John Wiley & Sons, 2016. a

Castillo, C., Taguas, E. V., Zarco-Tejada, P., James, M. R., and Gómez, J. A.: The normalized topographic method: an automated procedure for gully mapping using GIS, Earth Surf. Proc. Land., 39, 2002–2015, 2014. a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h

Colomina, I. and Molina, P.: Unmanned aerial systems for photogrammetry and remote sensing: A review, ISPRS J. Photogramm., 92, 79–97, 2014. a

Currier, K.: Mapping with strings attached: Kite aerial photography of Durai Island, Anambas Islands, Indonesia, J. Maps, 11, 589–597, 2015. a

Dandois, J. P. and Ellis, E. C.: Remote sensing of vegetation structure using computer vision, Remote Sens., 2, 1157–1176, 2010. a

Duffy, J. P. and Anderson, K.: A 21st-century renaissance of kites as platforms for proximal sensing, Prog. Phys. Geog., 40, 352–361, 2016. a

El Maaoui, M., Feurer, D., Planchon, O., Boussema, M., and Snane, M.: Assessment of kite borne DEM accuracy for gullies measuring, J. Res. Environ., 3, 118–124, 2015. a, b

Eltner, A., Kaiser, A., Castillo, C., Rock, G., Neugirg, F., and Abellán, A.: Image-based surface reconstruction in geomorphometry – merits, limits and developments, Earth Surf. Dynam., 4, 359–389, https://doi.org/10.5194/esurf-4-359-2016, 2016. a

Evans, M. and Lindsay, J.: High resolution quantification of gully erosion in upland peatlands at the landscape scale, Earth Surf. Proc. Land., 35, 876–886, 2010. a, b, c, d

Fonstad, M. A., Dietrich, J. T., Courville, B. C., Jensen, J. L., and Carbonneau, P. E.: Topographic structure from motion: a new development in photogrammetric measurement, Earth Surf. Proc. Land., 38, 421–430, 2013. a, b

Höfle, B., Griesbaum, L., and Forbriger, M.: GIS-Based Detection of Gullies in Terrestrial LiDAR Data of the Cerro Llamoca Peatland (Peru), Remote Sens., 5, 5851–5870, 2013. a, b, c, d, e

Inoubli, N., Raclot, D., Mekki, I., Moussa, R., and Le Bissonnais, Y.: A spatio-temporal multiscale analysis of runoff and erosion in a Mediterranean marly catchment, Vadose Zone Journal, 2017. a

Jaud, M., Passot, S., Le Bivic, R., Delacourt, C., Grandjean, P., and Le Dantec, N.: Assessing the accuracy of high resolution digital surface models computed by PhotoScan® and MicMac® in sub-optimal survey conditions, Remote Sens., 8, 465, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs8060465, 2016. a

Jinze, M. and Qingmei, M.: Sediment delivery ratio as used in the computation of watershed sediment yield, J. Hydrol. (New Zealand), 20, 27–38, 1981. a

Khalili, A. E., Raclot, D., Habaeib, H., and Lamachére, J. M.: Factors and processes of permanent gully evolution in a Mediterranean marly environment (Cape Bon, Tunisia), Hydrol. Sci. J., 58, 1519–1531, 2013. a

Lowe, D. G.: Distinctive image features from scale-invariant keypoints, Int. J. Comput. Vision, 60, 91–110, 2004. a

Marzolff, I. and Poesen, J.: The potential of 3D gully monitoring with GIS using high-resolution aerial photography and a digital photogrammetry system, Geomorphology, 111, 48–60, 2009. a, b, c, d

Marzolff, I., Ries, J. B., and Poesen, J.: Short-term versus medium-term monitoring for detecting gully-erosion variability in a Mediterranean environment, Earth Surf. Proc. Land., 36, 1604–1623, 2011. a

Mekki, I.: Analyse et modélisation de la variabilité des flux hydriques à l'échelle d'un bassin versant cultivé alimentant un lac collinaire du domaine semi-aride méditerranéen (Oued Kamech, Cap Bon, Tunisie), Phd thesis, Université des Sciences et Techniques du Languedoc, 2003. a

Mekki, I., Albergel, J., Mechlia, N. B., and Voltz, M.: Assessment of overland flow variation and blue water production in a farmed semi-arid water harvesting catchment, Phys. Chem. Earth, 31, 1048–1061, 2006. a

Mosbrucker, A. R., Major, J. J., Spicer, K. R., and Pitlick, J.: Camera system considerations for geomorphic applications of SfM photogrammetry, Earth Surf. Proc. Land., 42, 969–986, https://doi.org/10.1002/esp.4066, 2017. a

Murray, J. C., Neal, M. J., and Labrosse, F.: Development and deployment of an intelligent Kite Aerial Photography Platform (iKAPP) for site surveying and image acquisition, J. Field Robot., 30, 288–307, 2013. a

Nachtergaele, J. and Poesen, J.: Assessment of soil losses by ephemeral gully erosion using high-altitude (stereo) aerial photographs, Earth Surf. Proc. Land., 24, 693–706, 1999. a

Nex, F. and Remondino, F.: UAV for 3D mapping applications: a review, Appl. Geomat., 6, 1–15, 2014. a, b

Noto, L. V., Bastola, S., Dialynas, Y. G., Arnone, E., and Bras, R. L.: Integration of fuzzy logic and image analysis for the detection of gullies in the Calhoun Critical Zone Observatory using airborne LiDAR data, ISPRS J. Photogr. Remote Sens., 126, 209–224, 2017. a, b

Oh, P. Y. and Green, B.: A kite and teleoperated vision system for acquiring aerial images, in: IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, 1, 1404–1409, 2003. a

Orlandini, S., Tarolli, P., Moretti, G., and Dalla Fontana, G.: On the prediction of channel heads in a complex alpine terrain using gridded elevation data, Water Resour. Res., 47, W02538, https://doi.org/10.1029/2010WR009648, 2011. a

Passalacqua, P., Do Trung, T., Foufoula-Georgiou, E., Sapiro, G., and Dietrich, W. E.: A geometric framework for channel network extraction from lidar: Nonlinear diffusion and geodesic paths, J. Geophys. Res.-Earth, 115, F01002, https://doi.org/10.1029/2009JF001254, 2010. a

Passalacqua, P., Belmont, P., Staley, D. M., Simley, J. D., Arrowsmith, J. R., Bode, C. A., Crosby, C., DeLong, S. B., Glenn, N. F., Kelly, S. A., Lague, D., Sangireddy, H., Schaffrath, K., Tarboton, D. G., Wasklewicz, T., and Wheaton, J. M.: Analyzing high resolution topography for advancing the understanding of mass and energy transfer through landscapes: A review, Earth-Sci. Rev., 148, 174–193, 2015. a

Pierrot-Deseilligny, M. and Paparoditis, N.: A multiresolution and optimization-based image matching approach: An application to surface reconstruction from SPOT5-HRS stereo imagery, Archives of Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, 36, 1/W41, 73–77, 2006. a

Raclot, D. and Albergel, J.: Runoff and water erosion modelling using WEPP on a Mediterranean cultivated catchment, Phys. Chem. Earth, 31, 1038–1047, 2006. a

Radjou, N. and Prabhu, J.: Frugal Innovation: How to do more with less, The Economist, 2015. a

Rengers, F. K. and Tucker, G.: Analysis and modeling of gully headcut dynamics, North American high plains, J. Geophys. Res.-Earth, 119, 983–1003, 2014. a

Smith, M. J., Chandler, J., and Rose, J.: High spatial resolution data acquisition for the geosciences: kite aerial photography, Earth Surf. Proc. Land., 34, 155–161, 2009. a, b, c

Smith, M. W., Carrivick, J. L., and Quincey, D. J.: Structure from motion photogrammetry in physical geography, Prog. Phys. Geogr., 40, 247–275, 2016. a

Snavely, N., Seitz, S. M., and Szeliski, R.: Photo tourism: exploring photo collections in 3D, in: ACM transactions on graphics, 25, 835–846, 2006. a

Snavely, N., Seitz, S. M., and Szeliski, R.: Modeling the world from internet photo collections, Int. J. Comp. Vision, 80, 189–210, 2008. a

Stumpf, A., Malet, J.-P., Allemand, P., Pierrot-Deseilligny, M., and Skupinski, G.: Ground-based multi-view photogrammetry for the monitoring of landslide deformation and erosion, Geomorphology, 231, 130–145, 2015. a

Thommeret, N., Bailly, J. S., and Puech, C.: Extraction of thalweg networks from DTMs: application to badlands, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 14, 1527–1536, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-14-1527-2010, 2010. a, b, c

Van Westen, C. J.: Remote sensing and GIS for natural hazards assessment and disaster risk management, Treatise on geomorphology, 3, 259–298, 2013. a

Vandaele, K., Poesen, J., Govers, G., and van Wesemael, B.: Geomorphic threshold conditions for ephemeral gully incision, Geomorphology, 16, 161–173, 1996. a

Vaze, J., Teng, J., and Spencer, G.: Impact of DEM accuracy and resolution on topographic indices, Environ. Modell. Softw., 25, 1086–1098, 2010. a

Verhoeven, G., Taelman, D., and Vermeulen, F.: Computer vision-based orthophoto mapping of complex archaeological sites: the ancient quarry of Pitaranha (Portugal-Spain), Archaeometry, 54, 1114–1129, 2012. a

Verhoeven, G. J.: Providing an archaeological bird's-eye view–an overall picture of ground-based means to execute low-altitude aerial photography (LAAP) in Archaeology, Archaeol. Prospec., 16, 233–249, 2009a. a, b, c

Verhoeven, G. J., Loenders, J., Vermeulen, F., and Docter, R.: Helikite aerial photography–a versatile means of unmanned, radio controlled, low-altitude aerial archaeology, Archaeol. Prospec., 16, 125–138, 2009b. a, b

Vericat, D., Brasington, J., Wheaton, J., and Cowie, M.: Accuracy assessment of aerial photographs acquired using lighter-than-air blimps: low-cost tools for mapping river corridors, River Res. Appl., 25, 985–1000, 2009. a

Westoby, M., Brasington, J., Glasser, N., Hambrey, M., and Reynolds, J.: “Structure-from-Motion” photogrammetry: A low-cost, effective tool for geoscience applications, Geomorphology, 179, 300–314, 2012. a, b

Wigmore, O. and Mark, B.: High altitude kite mapping: evaluation of kite aerial photography (KAP) and structure from motion digital elevation models in the Peruvian Andes, Int. J. Remote Sens., 1–21, https://doi.org/10.1080/01431161.2017.1387312, 2017. a

Wundram, D. and Loeffler, J.: High-resolution spatial analysis of mountain landscapes using a low-altitude remote sensing approach, Int. J. Remote Sens., 29, 961–974, 2008. a, b, c