the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

An evaluation of the alignment of drought policy and planning guidelines with the contemporary disaster risk reduction agenda

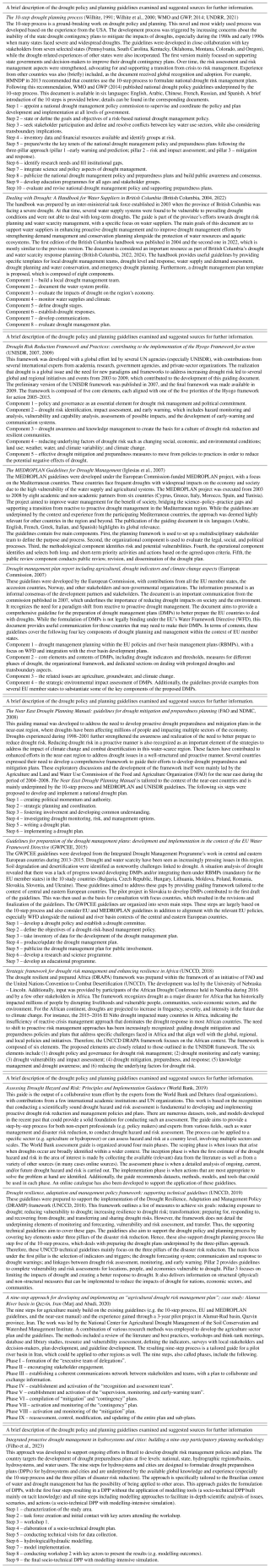

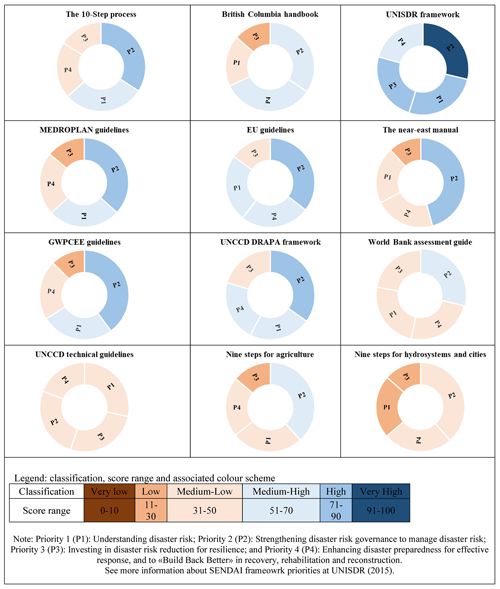

Drought is a major global challenge, causing significant socio-economic and environmental impacts. A paradigm shift from crisis to risk management is advocated for to reduce the impacts of droughts and to build the resilience of societies and water and environmental systems to drought. A number of drought policy and planning guidelines are developed and used to support the transition from crisis to risk management and enhancing resilience. However, research is lacking on critical reflection, evaluation, and updating of the available drought guidelines. For example, there is no study assessing the correspondence of the available guidelines to the contemporary disaster risk reduction agenda. Therefore, this study evaluates 12 sets of drought policy and planning guidelines for their alignment with the four priority areas of the SENDAI framework for disaster risk reduction 2015–2030. A qualitative evaluation matrix was developed and used in the assessment. The priorities and associated thematic elements examined were scored in the range of 0–100 and were classified into the very low (0–10), low (11–30), medium-low (31–50), medium-high (51–70), high (71–90), and very high (91–100) categories. Most guidelines achieved (medium-)high to very high scores on the data and information, risk assessment, and communication and dissemination elements associated with priority 1 (understanding disaster risk), while mostly very low to low coverage was found for science–policy–practice dialogue, local knowledge and practices, and research and development. Most guidelines earned high scores on strengthening disaster risk governance to manage disaster risk (priority 2), notably for strategies and plans, coordination mechanisms, community representation, and policy and governance. In contrast, most elements under priority 3 (investing in disaster risk reduction) were classified in the low to medium categories, which include financial allocation, risk transfer, mainstreaming drought risk reduction into land use and rural-development planning, business resilience and protection of livelihoods, and health and safety. Most elements under priority 4 (enhancing disaster preparedness) scored in the medium-low to medium-high ranges, as sufficient information was lacking on multi-hazard early-warning systems; post-disaster recovery, rehabilitation, and reconstruction; and the resilience of critical infrastructure. Furthermore, the study outlined several strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats pertaining to the guidelines examined. In general, the study reveals an urgent need to better align drought policy and planning guidelines with the contemporary disaster risk reduction agenda outlined in the SENDAI framework. The findings of this study can be instructive in designing the next generation of drought guidelines in support of an accelerated transition towards drought risk reduction and management and in building resilient societies and ecosystems under a changing climate and increasing anthropogenic pressures.

- Article

(2568 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(588 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Drought is a major global challenge. Many countries face drought every year and have to bear losses to a varying degree, depending upon multiple factors such as drought severity and duration, geographical extent, vulnerability, and resilience. There were 488 drought events recorded in the international disaster database (EM-DAT, 2024) during the last 30 years (1994–2023) (see Supplement, “Supplementary material 1”). The estimates suggest that these droughts affected about 2 billion people across the globe and caused economic damage of about USD 220 billion. A conservative estimate of the number of countries reporting drought in a year ranged from 6 (1995) to 29 (2015). The studies show that the drought events demonstrate local, regional, continental, and global coverage (Masih et al., 2014; Blauhut et al., 2022; Mondal et al., 2023). Drought impacts (directly or indirectly) various sectors such as agriculture, water management, energy, river transport, the environment, and public health (Wilhite et al., 2007; UNDRR, 2021; Rossi et al., 2023). These impacts can be short, medium, or long term and may occur over local, regional, and global scales. For example, the 2018–2020 drought event covered the largest area in Europe (36 %) compared to previous droughts (Rakovec et al., 2022). The duration of this event was estimated at 12.2 months, and the event was estimated to be the longest in the last 250 years. Central and western European countries were impacted most by this drought. Moreover, the study stressed the need to adopt European policies, plans, and strategies to cope with increasingly intense, long-duration, and widespread droughts. This is also a global need because drought occurrences and impacts are likely to increase in the future for many countries because of climate change (Spinoni et al., 2019; Naumann et al., 2021; Rakovec et al., 2022; IPCC, 2021, 2022) and human activities (Van Loon et al., 2022).

A paradigm shift in drought policy and practice from crisis to risk management is advocated for to reduce the impacts of droughts and to build the resilience of societies and water and environmental systems to drought (Wilhite, 1991; Wilhite et al., 2000; World Bank, 2012; Sivakumar et al., 2014; UNISDR, 2005, 2015; UNDRR, 2021). Wilhite (1991) and Wilhite et al. (2000) proposed a novel 10-step process to guide drought policy and planning processes in support of a transition towards risk management. The approach proposed was underpinned by the understanding and experience of science, policy, and practice from the USA. Similar to the 10-step process, the Mediterranean Drought Preparedness and Mitigation Planning (MEDROPLAN) drought guidelines were developed to support pro-active and risk-based approaches to address droughts in the Mediterranean region, which is highly vulnerability to droughts (Iglesias et al., 2007). Furthermore, the European Union (EU) drought guidelines recommend an integrated risk management approach, with a strong focus on making drought plans at the river basin level or integrating them as part of the river basin plans (European Commission, 2007). These guidelines also focus on drought management in relation to agriculture, climate change, transboundary cooperation, groundwater, sustainable development, and environmental impact assessment. Furthermore, UNISDR (2007, 2009) prepared a comprehensive drought risk reduction framework, which is aligned with the five priorities outlined in the Hyogo Framework for Action 2005–2015 (UNISDR, 2005). The UNISDR framework is based on five key elements: (1) policy and governance, (2) drought risk identification and early warning, (3) awareness and education, (4) reducing the underlying factors of drought risk, and (5) mitigation and preparedness. A few years later, in 2013, a high-level meeting on national drought policy (HMNDP) was held (Sivakumar et al., 2014). The final declaration of this landmark meeting notes that drought poses a serious challenge for the sustainable development of all countries and in particular developing countries. Many countries do not have sufficient policies for appropriate drought management and pro-active drought preparedness, and drought responses are often reactive (crisis management). Recent research corroborates this declaration, highlighting the variable degree of preparedness and the transition towards risk management within and across countries (Fu et al., 2013; Jedd et al., 2021; Blauhut et al., 2022; Jedd and Smith 2023; Biella et al., 2024). Moreover, HMNDP recognized the urgent need to develop risk management strategies and preparedness plans (Sivakumar et al., 2014), and the countries were encouraged to develop and implement national drought management policies and plans. An invitation was extended to update the relevant science and policy documents by aligning them with the recommendations made by HMNDP, which suggest focusing on developing pro-active drought management measures, enhancing collaboration and the quality of observation networks and delivery systems, improving public awareness, considering suitable economic and financial strategies, establishing emergency relief plans, and linking drought management plans to local/national development policies. Following from the HMNDP recommendations, the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) and Global Water Partnership (GWP 2014) proposed national drought management policy guidelines, which are based on the 10-step process (Wilhite 1991; Wilhite et al., 2000).

Building on the Hyogo framework, the SENDAI framework for disaster risk reduction 2015–2030 acknowledges the challenges posed by multiple disasters, despite progress made during the past decades (UNISDR, 2015). The SENDAI framework presents four priorities for action: priority 1 is understanding disaster risk, priority 2 is strengthening disaster risk governance to manage disaster risk, priority 3 is investing in disaster risk reduction for resilience, and priority 4 is enhancing disaster preparedness for effective response and “build[ing] back better” in recovery, rehabilitation, and reconstruction. Additionally, the UNISDR Strategic framework 2016–2021 highlights the contribution of disaster risk reduction to the achievement of the global sustainable development agenda (UNISDR, 2017). There are a few sets of drought guidelines developed after the SENDAI framework was created (UNCCD, 2018, 2019; World Bank, 2019; Marj and Abadi, 2020; Filho et al., 2023). However, there is a lack of information on how these guidelines consider the goals and priorities of the SENDAI framework and related global disaster risk reduction agendas. Nevertheless, most recent guidelines (UNCCD, 2019; World Bank, 2019) highlight the importance of the three pillars of drought risk reduction (Tsegai et al., 2015; Verbist et al., 2016), which include drought monitoring and early warning (pillar 1), vulnerability and impact assessment (pillar 2), and drought mitigation and preparedness measures (pillar 3). These three pillars are a subset of the elements outlined as the priorities of the SENDAI framework and also reflect the components included in the declaration of HMNDP.

In general, there are a number of drought policy and planning guidelines developed before and after the SENDAI framework. However, there is a lack of understanding of how the available guidelines align with the contemporary disaster risk reduction agenda. Furthermore, adjusting drought policy and plans to the contemporary drought thinking and changing needs is essential to accelerate progress toward drought risk reduction and to build the resilience of societies to drought under changing climate and increasing anthropogenic pressures. While several sets of global, regional, and local guidelines have been developed over the past 50 years, the research is lacking on critical reflection, evaluation, and updating of these guidelines. To date, there is no study, to the author's knowledge, assessing the correspondence between the available drought guidelines and the contemporary disaster risk reduction agenda. Therefore, this study evaluates the drought policy and planning guidelines for their alignment with the four priority areas delineated in the SENDAI framework for disaster risk reduction 2015–2030. Furthermore, the study explores strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats and provides insights to better align future generations of drought guidelines with the contemporary disaster risk reduction agenda.

The drought policy and planning guidelines were found through multiple internet sources such as Scopus, Google and Google Scholar. The document search also benefited from the author's knowledge gained through education and capacity development activities related to drought management, including teaching on the drought policy and planning guidelines. Various keywords were used to find the guidelines, which were mainly centred around drought policy, drought planning, drought guidelines, drought policy and planning frameworks, and drought risk management. The search resulted in the selection of 12 sets of guidelines published as journal articles and reports in the English language. A brief description of these guidelines and the main references for further information are provided in Table 1. A few more insightful documents and web sources were found (EDO, 2024; IDMP, 2024; NDMC Planning, 2024; Steinemann and Cavalcanti, 2006; UNISDR et al., 2009; Rossi et al., 2007; Rossi and Castiglione, 2011; WMO and GWP, 2016; Cook et al., 2017; Vogt et al., 2018; CISA, 2021; Vogel and Kroll, 2021; Walker et al., 2024) but were not selected for evaluation because of their limited scope compared to this study's objectives, the lack of details needed to conduct the evaluation, or a very high degree of similarity with the guidelines selected. The list of guidelines evaluated is not exhaustive, but it is sufficient for the purpose of this study.

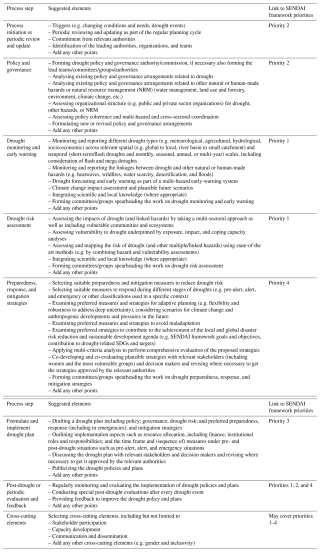

Table 2Description and classification scheme of the evaluation matrix developed and used in this study.

A qualitative scoring matrix was developed and used in the evaluation (Table 2). The four priority areas of the SENDAI framework, along with their corresponding elements, were scored on a scale of 0–100 (very low – 0–10; low – 11–30; medium-low – 31–50; medium-high – 51–70; high – 71–90; and very high – 91–100). The evaluation grid used in this study is similar to the one used to monitor the progress toward Sustainable Development Goal 6 (SDG6) indicator 6.5 and toward target 6.5.1 of the integrated water resources management (IWRM; UNEP, 2021). While the scoring ranges and classes used in this study are similar to those applied for IWRM evaluation, a novel scoring grid was formulated corresponding to the objectives of this study (Table 2). Additionally, the work carried out by Fu et al. (2013), Jedd et al. (2021), and Jedd and Smith (2023) to evaluate drought and drought-related policies and plans was instructive in formulating the evaluation methods for this research. For the evaluation, first, each core element in a certain priority area was scored and categorized. Then, an average score was calculated for the priority area. All elements were assigned equal weights in estimating the overall score. Furthermore, a strength, weakness, opportunity, and threat (SWOT) analysis was carried out. The elements scored in the high to very high categories for most of the guidelines were considered to be strengths. Weaknesses were identified based on elements scored in the very low to low categories in most cases. Opportunities represent areas with medium or good coverage by a few sets of guidelines and demonstrate the potential to translate into strengths with minimal efforts. Threats correspond to insufficient coverage by emerging science–policy–practice discourses in the field of disaster risk reduction, in particular, drought risk management. Ignoring or paying limited attention to these important discourses may significantly undermine the quality and effectiveness of the drought policy and planning guidelines for the future.

The evaluation results need to be interpreted with caution, owing to the inherent uncertainties associated with the evaluation process. Considering this, the overall ratings in terms of categories are used in the interpretation and discussion of the results rather than focusing on actual scores. However, the evaluation remarks alongside the scores are provided in the Supplement for reference (“Supplementary material 2”). It is pertinent to note that, in some cases, the assigned scores were very close to the border of two categories. These cases show a comparatively higher degree of uncertainty in their classification compared to the situations when the scores were in the middle of a category. Alongside the acknowledgement of these uncertainties, it is assumed that the overall pattern of scoring is likely to stay the same in most cases even if a few elements are rated a bit differently within the expected uncertainty range of one category. Therefore, the main patterns of the results and the emerging insights are considered reliable and instructive for further discussion by, application to, and research by the science–policy–practice community concerned with drought management.

Moreover, I acknowledge that the terms “disaster risk reduction” and “disaster risk management” are often used interchangeably and are not easily distinguishable. However, this work recommends following the meanings outlined by UNDRR (2017):

Disaster risk management is the application of disaster risk reduction policies and strategies to prevent new disaster risk, reduce existing disaster risk and manage residual risk, contributing to the strengthening of resilience and reduction of disaster losses. While disaster risk reduction is aimed at preventing new and reducing existing disaster risk and managing residual risk, all of which contribute to strengthening resilience and therefore to the achievement of sustainable development. Disaster risk reduction is the policy objective of disaster risk management, and its goals and objectives are defined in disaster risk reduction strategies and plans.

The guidelines examined in this study aim to support developing polices, plans, and strategies in support of both disaster risk reduction and management aspects.

3.1 Performance compared to the SENDAI framework priorities

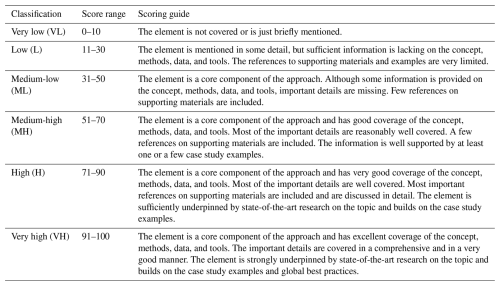

The evaluation results for the four priority areas of the SENDAI framework and underpinning thematic elements are presented in Table 3. Under priority 1 (understanding the disaster risk), drought risk assessment and data and information are the two best-covered themes, which received high to very high scores in most of the guidelines evaluated. Communication and dissemination are mostly scored in the medium to high categories. In contrast, four thematic areas scored poorly in most cases. These include local knowledge and practices, capacity development, science–policy–practice dialogue, and research and development. These areas tend to receive lower coverage over time, as most of the guidelines developed after 2009 obtained lower scores compared to the earlier documents. For example, science–policy–practice was covered well by the 10-step process, MEDROPLAN guidelines, and UNISDR framework. The remaining sets of guidelines evaluated, including the most recent ones, do not provide good coverage of these topics.

Table 3The evaluation results of the alignment of the guidelines examined with the four priority areas of the SENDAI framework.

Most of the sets of guidelines evaluated scored high to very high in all thematic areas falling under disaster risk governance (priority 2). For instance, the UNISDR framework provides very good to excellent coverage of this priority area. A few other sets of guidelines scoring high include the UNCCD DRAPA framework, the GWPCEE guidelines, the 10-step process, the MEDROPLAN guidelines, and the EU guidelines. However, the four most-recent guidelines developed during 2019-2023 (World Bank assessment guide, UNCCD technical guidelines, nine steps for agriculture, and nine steps for hydrosystems and cities) obtained comparatively low scores. These guidelines scored very low to low for political will, low to medium low for periodic assessment and reporting, and medium-low to medium-high for policy and governance aspects. The most recent guidelines place a very high emphasis on covering the three pillars of drought risk reduction and tend to give less attention to other important themes linked to the SENDAI framework. In contrast, drought risk reduction strategies and plans received good to excellent coverage by the guidelines evaluated. Similarly, stakeholder participation, including community engagement and coordination mechanisms within or across multiple sectors, are very well covered in most cases.

The scores for priority 3 (investing in disaster risk reduction for resilience) were very low to low in most cases. Only 1 of the 12 sets of drought guidelines, the UNISDR framework, scored in the medium-high to high range for the key elements under priority 3. The remaining 11 sets of guidelines mostly achieved (very) low to medium scores. For example, resource allocation (especially finances) and risk transfer (including insurance) are either not core elements or lack sufficient coverage in most cases. Similarly, mainstreaming drought risk reduction into land use policies and rural-development plans lacked sufficient attention. Business resilience, protection of livelihoods and productive assets, and health and safety are classified under the very low to low categories because of insufficient coverage. However, sustainable use and management of the ecosystem received variable coverage, as a few sets of guidelines (UNISDR and UNCCD DRAPA frameworks, EU and GWPCEE guidelines) provide good to very good coverage of this theme. Last but not least, most thematic areas under priority 4 are rated in the low to medium categories. An exception is the topic of disaster preparedness and contingency policies, plans, and programmes, which received medium to high coverage in most cases. However, the least amount of attention was paid to elements related to post-disaster recovery, rehabilitation, and reconstruction; resilience of critical infrastructure; and multi-hazard forecasting and early-warning systems.

3.2 Overall assessment and SWOT analysis

Figure 1 shows the average ratings of the guidelines examined compared to each of the four priority areas of the SENDAI framework. In general, none of the sets of guidelines examined align very well with all four priority areas of the SENDAI framework. Nevertheless, the UNISDR framework performed better compared to other guidelines examined in this study, even though it needs considerable improvement for priorities 3 and 4. Contrary to expectations, the most widely adopted 10-step process was not able to score very high on any of the four priority areas but scored medium-low on two of the four priorities (3 and 4), medium-high on priority 2, and high on priority 1. A couple of the sets of guidelines examined (UNCCD technical guidelines and World Bank assessment guide) are focused on a few thematic areas, such as addressing the three pillars of disaster risk reduction, and scored high to very high on these elements but achieved low to medium overall scores on all four priorities. On the other hand, the two most-recent guidelines (nine steps for agriculture and nine steps for hydrosystems and cities), aiming to provide a comprehensive drought planning process, also achieved lower scores in general. Similarly, the regional guidelines (the near-east manual, the UNCCD-DRAPA framework, and the MEDROPLAN and EU guidelines) achieve low to medium scores in most cases. Furthermore, building on these evaluation results, the SWOT analysis was conducted, which is summarized in Fig. 2 and discussed below.

3.2.1 Strengths

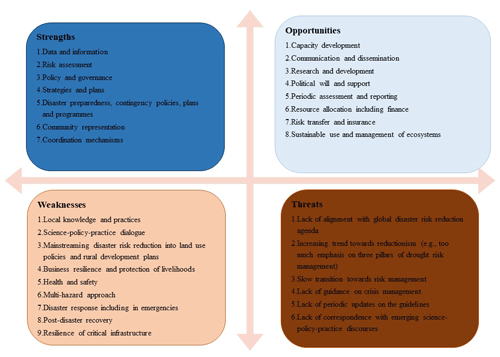

There are several areas that are covered (very) well by most of the sets of guidelines (strengths), including data and information, risk assessment, policies and plans, coordination, and stakeholder participation (Fig. 2). These areas should be kept during new developments, updates, or applications, as these subjects will require few to moderate efforts to adjust to the scope and context of the new guidelines. The available guidelines provide a detailed account of the state of the art related to these topics, which can be very instructive for future work. For example, drought risk assessment is covered very well by the 10-step process, MEDROPLAN guidelines, UNISDR framework, UNCCD technical guidelines, and World Bank assessment guide. The concepts, methods, and data to assess drought hazard, exposure, impact, and coping capacity are explained very well in most of these documents. Moreover, combining various factors in assessing drought vulnerability and risk is clearly outlined. These guidelines also provide good to very good coverage of the aspects related to data and information, policies and plans, coordination, and stakeholder participation and can, therefore, serve as an excellent reference for future work updating the guidelines or applying them in practice. For example, WMO and GWP (2014) provide a synthesis of core elements of drought risk management policies and plans (Box 1), which is based on the recommendations from various guiding documents (e.g. the 10-step process, UNISDR framework) and consensus from the HMNDP held in 2013 (Sivakumar et al., 2014). The Drought Resilience +10 Conference held in 2024 took stock of the progress made and challenges faced during the past decade and issued key recommendations for the future (IDMP, 2024). These recommendations are highly valuable and are instructive for making contemporary drought risk management policies and plans in the future (Box 1).

3.2.2 Weaknesses

Nine areas were identified as weaknesses (Fig. 2), which require urgent attention. Making progress in these areas will require an inquiry beyond the drought guidelines available, which provide limited information on these aspects. For example, the drought guidelines examined lacked good coverage of people-centred multi-hazard, multi-sectoral forecasting and early-warning systems. For example, the GWPCEE guidelines briefly mention the need for an integrated approach that focuses on managing risks from droughts, floods, and climate change. The measures could be assessed using a multi-criteria approach. While multiple sectors impacted by drought are mentioned, tailoring early-warning systems to cater to the needs of various sectors is not yet well developed and remains poorly covered. Additionally, the guidelines examined lacked sufficient focus on establishing linkages between drought and other natural and/or human-made hazards such as wildfires, heatwaves, desertification, water scarcity, and floods. However, the available scientific research and some practice documents can contribute to the transformation of the outlined weaknesses to strengths. For example, the available literature can be helpful to understand the linkages between drought and other hazards, such as drought and desertification (Stringer et al., 2009; UNCCD, 2022; Oswald and Harris, 2023), floods and droughts (Ward et al., 2020; Browder et al., 2021), droughts and water scarcity (El Kharraz et al., 2012; Van Loon and Van Lanen, 2013; IDMP, 2022), droughts and wildfires (Littell et al., 2016; Brando et al., 2019; Nones et al., 2024), and compound events in general (Zscheischler et al., 2018). Similarly, available studies can provide useful guidance to strengthen information on multi-hazard early-warning systems (e.g. Aguirre-Ayerbe et al., 2020; Hemachandra et al., 2021; UNDRR and WMO, 2023).

Understanding, assessing, and reducing the underlying causes of disaster risk in a systematic manner; considering hydrological, ecological, and social system dynamics; and comprehending the inter-linkages, feedback mechanisms, and compound and cascading impacts would contribute to building resilience to drought and related (multiple) hazards (Hagenlocher et al., 2023; Van Loon et al., 2024). For instance, sustainable land and water management practices can contribute to the fight against both drought and desertification. Additionally, these measures, including nature-based solutions, may also help maintain (or enhance) soil saturation, infiltration capacity, and water storage in the catchments, which could contribute to a reduction in flood risk during and after drought when high and intense rainfall event may occur and cause flash floods. However, these and other strategies and measures would require a sound understanding of the social and technical aspects of the local natural and human systems. A well-informed and proactive social and political response could greatly contribute to the successful implementation of drought response, mitigation, and preparedness measures, including sustainable land management practices, people-centred multi-hazard forecasting, and early-warning systems.

3.2.3 Opportunities

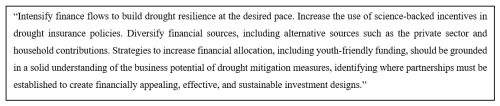

Seven opportunities were identified (Fig. 2). These areas can be enhanced, capitalizing on the information already available in the examined guidelines. For example, the UNISDR framework provides a good description of investments for prevention, mitigation, and preparedness measures, underpinning them with examples of and references to various investment sources. Similarly, the 10-step process and UNCCD DRAPA framework recommend innovative financial mechanisms alongside funding from various sources such as public and private investments, while the MEDROPLAN guidelines, UNISDR framework, and UNCCD technical guidelines contain some useful insights into risk transfer and insurance and safety nets, alongside a few good examples. Additional insights from multiple sources could provide useful material to strengthen these aspects of future drought guidelines (see, for example, Tadesse et al., 2015; Kron et al., 2016; World Bank, 2022; ADB and IDMC, 2024; IDMP, 2024; World Bank and European Commission, 2024). A quotation is provided below as an example to highlight recent insights into and recommendations for drought finance and risk transfer (Box 2).

Box 2A recommendation from the finance work stream of the Drought Resilience +10 Conference held in 2024 (source – IDMP, 2024).

Over the past few decades, several countries have made drought policies and plans using global, regional, and/or local guidelines (Guido et al., 2023; IDMP, 2024; NDMC Planning, 2024). These policies and plans offer a great opportunity for cross-learning on the contextualized development and application of drought policy and planning guidelines. For example, several sets of guidelines enumerate potential drought risk management measures, which could serve as a good starting point for screening, evaluating, and implementing suitable measures for a given context. An example case could be the drought management measures recommended in the EU Commission's guidelines (European Commission, 2007) and a critical assessment of the varying degrees of consideration of these measures in the drought management and drought-related plans and strategies developed by the EU member states (Guido et al., 2023). For instance, determining the usage priorities during drought situations is a measure recommended by EU guidelines, which is an important drought risk management measure that does not prominently feature in many guidelines. A critical analysis by Guido et al. (2023) on the status at the EU level suggests that 16 countries have established water allocation priorities at various levels (e.g. national, river basin, and local levels). In most cases, critical infrastructure use, domestic use, and the environment are among the top three priorities, followed by other uses/sectors (e.g. agriculture and industry), while navigation and recreational uses mostly receive the lowest priority. In contrast, several EU member states still need to establish water use priorities for drought. These and other such countries can learn from the examples available, even though the available cases may have some gaps. It is important to recognize that the factors considered in defining the water allocation priority may vary across countries and may include elements like the water account/balance situation, types of use, age and location of entitlements, differential profitability, severity of drought and water use restrictions, and exemptions during drought (e.g. for environmental/ecological flows as stipulated in the EU's WFD). Despite reasonably good coverage of various important factors, comprehensively considering criteria related to sustainability, efficiency and/or equity of water use is recommended in establishing water use priorities.

3.2.4 Threats

The major threats include a lack of alignment with the global disaster risk reduction agenda, an increasing trend towards reductionism, a slow transition towards risk management, a lack of guidance for crisis management, and a lack of periodic updates of the guidelines (Fig. 2). For example, to date, there is no set of guidelines specifically designed to align with the contemporary science–policy–practice discourses and global disaster risk reduction agenda, i.e. the SENDAI framework. Only the UNISDR framework was drafted in response to the Hyogo framework for action 2005–2015; hence, it aligns very well with its priority areas but requires a significant update to two of the four priority areas of the SENDAI framework (priorities 3 and 4). Furthermore, too much emphasis on risk management may be counterproductive, as the focus on crisis management receives little or no attention. This is demonstrated by the weak coverage of disaster response, including in emergencies and post-disaster recovery, rehabilitation, and reconstruction. None of the sets of guidelines evaluated provide comprehensive coverage of the key elements pertaining to the crisis management. Nevertheless, one of the 12 sets of guidelines, the British Columbia handbook published in 2004 (British Columbia, 2004), contains useful information on emergency response planning. Last but not least, the available guidelines lacked correspondence with the contemporary research and development discourses and can benefit from the available literature in these areas. Examples include but are not limited to understanding drought in the Anthropocene (Van Loon et al., 2016, 2022, Cook et al., 2022; Hall et al., 2022); the transition to sustainability and achieving sustainable development goals (SDGs), where drought management is an important contributor (Zhang et al., 2019; UNDRR, 2022; Tabari and Willems, 2023); assessing climate change impacts and adaptation options (Stringer et al., 2009; Cook et al., 2018; C2ES, 2018; Dai et al., 2018; Mukherjee et al., 2018; Iglesias et al., 2021); addressing maladaptation (Christian-Smith et al., 2015; Ward et al., 2020; Filho et al., 2022; Reckien et al., 2023; Tubi and Israeli, 2024); and managing the risk from flash (Otkin et al., 2018; Christian et al., 2021; Yuan et al., 2023) and mega droughts (Gober et al., 2016; Garreaud et al., 2020; Cook et al., 2022).

3.3 Making a transition towards the next generation of drought policy and planning guidelines

Since the available drought policy and planning guidelines do not align very well with the contemporary disaster risk reduction agenda, there is an urgent need to revise and improve them or to develop new guidelines. This is essential to accelerate the progress of the transition towards risk reduction and management, building resilience, and sustainability. At a global level, efforts could be dedicated to revisiting the available guidelines. For example, the UNISDR framework could be improved to better align with the SENDAI framework priorities. Moreover, the 10-step process could be updated, as it is very valuable and is the most widely recommended drought guide, but it has not been significantly updated since the work of Wilhite et al. (2000). Similarly, regional or local guidelines need considerable improvements in several areas. On the one hand, some guidelines may be a result of dedicated projects, and it may be difficult to revisit them after the project finishes. On the other hand, just like policies and plans need periodic evaluation and revision, so do the guidelines underpinning them. Thus, the drought guidelines are not meant to be static. Therefore, making concerted efforts at global, regional, national, and local levels to dynamically update the guidelines is highly recommended so that these correspond well with contemporary thinking and changing needs. There are several institutions and groups (e.g. UN agencies, academia, research groups, donors, and public- and private-sector organizations) that can (naturally) play a leading role in taking up this urgent call, as these institutions have a mandate and have made significant contributions to guiding drought policy, planning, and practical implementation in the past.

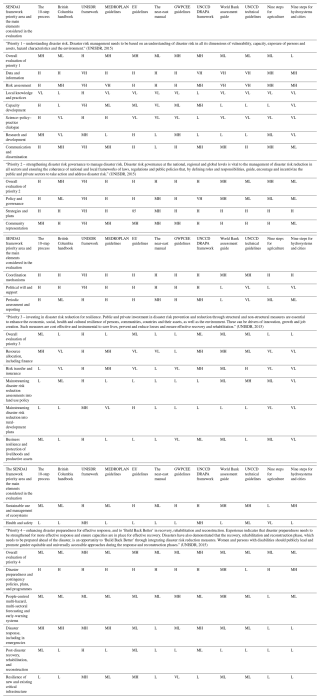

Figure 3Schematic representation of the key steps and elements that support the development of the next generation of drought policy and planning guidelines.

The information presented in this research can provide useful insights for both the developers and the users of the drought guidelines to move towards the next generation of drought policy and planning guidelines. Developing guidelines requires large investments and collaborative efforts from multiple stakeholders. Therefore, developing new or updated guidelines is beyond the scope of this research. Nevertheless, a contemporary framework is provided to facilitate this process (Fig. 3). The proposed framework is underpinned by the valuable information available in the existing sets of guidelines and by the new insights generated from this study. The framework contains seven main steps and a few cross-cutting elements linked to each step. Additionally, the process steps, potential thematic elements, and linkages with the SENDAI framework priorities are briefly mentioned in Table 4. In general, the proposed framework is flexible and could be adapted to the users' needs, for example, by adding another step or a cross-cutting element or by establishing linkages with relevant global, regional, national, and local policies.

A number of sets of drought policy and planning guidelines have been developed and used over the last few decades. However, there is a lack of understanding of the alignment of these guidelines with the contemporary disaster risk reduction agenda. This study evaluated 12 sets of drought policy and planning guidelines for their alignment with the four priority areas of the SENDAI Framework for disaster risk reduction 2015–2030. The study shows that the available guidelines stress the need for a transition from crisis to risk management. However, despite providing useful instructions, transitioning towards risk management and building resilience is still a global challenge. While global disaster risk reduction agendas have attempted to keep pace by addressing emerging challenges, the drought policy and planning guidelines have not responded sufficiently to these new developments.

This study concludes that the current drought guidelines do not align very well with the contemporary disaster risk reduction agenda. While the available guidelines do provide very valuable instructions related to several important areas (e.g. data and information, risk assessment, coordination mechanisms and stakeholder participation, policy and governance, preparedness plans, and communication and dissemination), there are a number of key elements that require substantial improvement (e.g. local knowledge and practices; resource allocation, including finance; risk transfer and insurance; mainstreaming drought risk reduction into land use and rural-development policies; post-disaster recovery; rehabilitation and reconstruction; business resilience and protection of livelihoods; health and safety; resilience of critical infrastructure; and science–policy–practice dialogue). The drought policy and planning guidelines need periodic revisions to remain valid and able to address contemporary challenges and needs. Therefore, updating the drought guidelines after every 10 to 15 years in the light of new developments in the relevant agendas and scientific knowledge is recommended. Finally, this research calls for urgent and overdue action to make concerted efforts in developing the next generation of drought policy and planning guidelines. The wealth of information available through previous work and new insights from science–policy–practice arenas can substantially contribute to these developments, supporting the accelerated transition towards improved drought risk reduction and management and building the resilience of societies and ecosystems to droughts under changing climate and increasing anthropogenic pressures.

The study is based on a document analysis. No datasets were used in this article.

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-25-2155-2025-supplement.

The author has declared that there are no competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors.

This article is part of the special issue “Drought, society, and ecosystems (NHESS/BG/GC/HESS inter-journal SI)”. It is not associated with a conference.

This work was developed as part of IHE Delft's general education, capacity development, and research activities on drought risk management. Most of the work was conducted in IHE Delft's MSc programme module on drought risk management and as a part of IHE Delft's DUPC2 programme project “Supporting integrated and sustainable water management in Iraq through capacity development and research”, grant no. 109070, which included the development of a tailor-made training course on drought risk assessment and management. Presentation of part of this research work at the Drought Resilience +10 Conference held in Geneva, Switzerland, from 30 September to 2 October 2024 and participation in the conference were very helpful in discussing ideas with a few international experts in the field. The funding to attend this important conference was generously provided by the EU Horizon 2020 project I-CISK (Innovating climate services through integrating scientific and local knowledge) under grant agreement no. 101037293 and by IHE Delft's Department of Water Resources and Ecosystem.

This research has been partially supported by IHE Delft's DUPC2 Programme (grant no. 109070) and EU Horizon 2020 project I-CISK (grant no. 101037293).

This paper was edited by Khalid Hassaballah and reviewed by Ana Iglesias and one anonymous referee.

ADB and IDMC: Harnessing development financing for solutions to displacement in the context of disasters and climate change in Asia and the Pacific, Asian Development Bank and Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, 64 pp., ISBN 978-92-9270-910-5, 2024.

Aguirre-Ayerbe, I., Merino, M., Aye, S. L., Dissanayake, R., Shadiya, F., and Lopez, C. M.: An evaluation of availability and adequacy of Multi-Hazard Early Warning Systems in Asian countries: A baseline study, Int. J. Disast. Risk Re., 49, 101749, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101749, 2020.

Biella, R., Shyrokaya, A., Ionita, M., Vignola, R., Sutanto, S., Todorovic, A., Teutschbein, C., Cid, D., Llasat, M. C., Alencar, P., Matanó, A., Ridolfi, E., Moccia, B., Pechlivanidis, I., van Loon, A., Wendt, D., Stenfors, E., Russo, F., Vidal, J.-P., Barker, L., de Brito, M. M., Lam, M., Bláhová, M., Trambauer, P., Hamed, R., McGrane, S. J., Ceola, S., Bakke, S. J., Krakovska, S., Nagavciuc, V., Tootoonchi, F., Di Baldassarre, G., Hauswirth, S., Maskey, S., Zubkovych, S., Wens, M., and Tallaksen, L. M.: The 2022 Drought Needs to be a Turning Point for European Drought Risk Management, EGUsphere [preprint], https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-2024-2069, 2024.

Blauhut, V., Stoelzle, M., Ahopelto, L., Brunner, M. I., Teutschbein, C., Wendt, D. E., Akstinas, V., Bakke, S. J., Barker, L. J., Bartošová, L., Briede, A., Cammalleri, C., Kalin, K. C., De Stefano, L., Fendeková, M., Finger, D. C., Huysmans, M., Ivanov, M., Jaagus, J., Jakubínský, J., Krakovska, S., Laaha, G., Lakatos, M., Manevski, K., Neumann Andersen, M., Nikolova, N., Osuch, M., van Oel, P., Radeva, K., Romanowicz, R. J., Toth, E., Trnka, M., Urošev, M., Urquijo Reguera, J., Sauquet, E., Stevkov, A., Tallaksen, L. M., Trofimova, I., Van Loon, A. F., van Vliet, M. T. H., Vidal, J.-P., Wanders, N., Werner, M., Willems, P., and Živković, N.: Lessons from the 2018–2019 European droughts: a collective need for unifying drought risk management, Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci., 22, 2201–2217, https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-22-2201-2022, 2022.

Brando, P. M., Paolucci, L., Ummenhofer, C. C., Ordway, E. M., Hartmann, H., Cattau, M. E., Rattis, L., Medjibe, V., Coe, M. T., and Balch, J.: Droughts, wildfires, and forest carbon cycling: A pantropical synthesis, Annu. Rev. Earth Pl. Sc., 47, 555–581, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-earth-082517-010235, 2019.

British Columbia: Dealing with drought: A handbook for water suppliers in British Columbia, Land and Water British Columbia INC., 66 pp., ISBN 0-7726-5199-X, 2004.

British Columbia: Dealing with drought: a handbook for water suppliers in British Columbia, Updated August 2022, British Columbia Deputy Ministers' Committee on Drought, Ministry of Environment, 30 pp., ISBN 0-7726-5199-X, 2022.

British Columbia: British Columbia drought and water scarcity response plan, Ministry of Water, Land and Resource Stewardship, 63 pp., https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/environment/air-land-water/water/drought-info/drought_response_plan_final.pdf (last access: 3 March, 2024), 2024.

Browder, G., Sanchez, A. N., Jongman, B., Engle, N., Van Beek, E., Errea, C., and Hodgson, S.: An EPIC response: innovative governance for flood and drought risk management, World Bank, Washington, DC, 193 pp., https://hdl.handle.net/10986/35754 (last access: 29 June 2025), 2021.

C2ES (Center for Climate and Energy Solutions): Resilience strategies for Drought, Center for Climate and Energy Solutions, 18 pp., https://www.c2es.org/document/resilience-strategies-for-drought/ (last access: 29 June 2025), 2018.

Christian, J. I., Basara, J. B., Hunt, E. D., Otkin, J. A., Furtado, J. C., Mishra, V., Xiao, X., and Randall, R. M.: Global distribution, trends, and drivers of flash drought occurrence, Nat. Commun., 12, 6330, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-26692-z, 2021.

Christian-Smith, J., Levy, M. C., and Gleick, P. H.: Maladaptation to drought: a case report from California, USA, Sustain. Sci., 10, 491–501, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-014-0269-1, 2015.

CISA (Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency): Drought and infrastructure: a planning guide, Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency with the National Drought Resilience Partnership, produced with U.S. Department of Agriculture, Environmental Protection Agency, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and Federal Emergency Management Agency, 10 pp., https://www.cisa.gov/sites/default/files/2025-03/drought-and-infrastructure-planning-guide-MAR2025.pdf (last access: 29 June 2025), 2021.

Cook, C., Gavin, H., Berry, P., Guillod, B., Lange, B., Rey Vicario, D., and Whitehead, P.: Drought planning in England: a primer. Environmental Change Institute, University of Oxford, UK, 40 pp., ISBN 978-1-874370-67-3, 2017.

Cook, B. I., Mankin, J. S., and Anchukaitis, K. J.: Climate change and drought: from past to future, Current Climate Change Reports, 4, 164–179, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40641-018-0093-2, 2018.

Cook, B. I., Smerdon, J. E., Cook, E. R., Williams, A. P., Anchukaitis, K. J., Mankin, J. S., Allen, K., Andreu-Hayles, L., Ault, T. R., Belmecheri, S., and Coats, S.: Megadroughts in the common era and the anthropocene, Nature Reviews Earth & Environment, 3, 741–757, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43017-022-00329-1, 2022.

Dai, A., Zhao, T., and Chen, J.: Climate change and drought: a precipitation and evaporation perspective, Current Climate Change Reports, 4, 301–312, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40641-018-0101-6, 2018.

EDO: European Drought Observatory, Copernicus, https://drought.emergency.copernicus.eu/, last access: 30 August 2024.

El Kharraz, J., El-Sadek, A., Ghaffour, N., and Mino, E.: Water scarcity and drought in WANA countries, Procedia Engineer., 33, 14–29, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2012.01.1172, 2012.

EM-DAT: The International Disaster Database, https://www.emdat.be/, last access: 15 June 2024.

European Commission (EC): Drought management plan report including agricultural, drought indicators and climate change aspects, Water Scarcity and Droughts Expert Network, Technical report 2008-023, 132 pp., http://fis.freshwatertools.eu/files/MARS_resources/Info_lib/EEA(2007)Drought%20Management%20Plan%20Report.pdf (last access: 29 June 2025), 2007.

FAO and NDMC: The Near East Drought Planning Manual: guidelines for drought mitigation and preparedness planning, FAO, Rome, Italy, 59 pp., ISBN 978-92-5-106046-9, 2008.

Filho, F. A. S., Studart, T. C., and Filho, J. D. P.: Integrated proactive drought management in hydrosystems and cities: building a nine-step participatory planning methodology, Nat. Hazards, 115, 2179–2204, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-022-05633-z, 2023.

Filho, L. W., Totin, E., Franke, J. A., Andrew, S. M., Abubakar, I. R., Azadi, H., Nunn, P. D., Ouweneel, B., Williams, P. A., Simpson, N. P., and Global Adaptation Mapping Initiative Team: Understanding responses to climate-related water scarcity in Africa, Sci. Total Environ., 806, 150420, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.150420, 2022.

Fu, X., Svoboda, M., Tang, Z., Dai, Z., and Wu, J.: An overview of US state drought plans: crisis or risk management?, Nat. Hazards, 69, 1607–1627, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-013-0766-z, 2013.

Garreaud, R. D., Boisier, J. P., Rondanelli, R., Montecinos, A., Sepúlveda, H. H., and Veloso-Aguila, D.: The central Chile mega drought (2010–2018): a climate dynamics perspective, Int. J. Climatol., 40, 421–439, https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.6219, 2020.

Gober, P., Sampson, D. A., Quay, R., White, D. D., and Chow, W. T.: Urban adaptation to mega-drought: anticipatory water modeling, policy, and planning for the urban Southwest, Sustain. Cities Soc., 27, 497–504, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2016.05.001, 2016.

Guido, S., do Ó, A., Markowska, A., Benítez-Sanz, C., Tetelea, C., Cinova, D., Stonevičius, E., Kampa, E., Vroom, I., Fehér, J., Rouillard, J., Väljataga, K., Navas, L., Blanka, L., De Stefano, S., Jones, M., Dekker, M., Gustafsson, O., Lundberg, P., Pengal, P., Geidel, T., Dworak, T., Zamparutti, T., and Lukacova, Z.: Stock-taking analysis and outlook of drought policies, planning and management in EU Member States, Final report for the European Commission, Directorate-General for Environment, 123 pp., ISBN 978-92-68-10284-8, 2023.

GWPCEE (Global Water Partnership Central and Eastern Europe): Guidelines for the preparation of drought management plans: development and implementation in the context of the EU Water Framework Directive, Global Water Partnership Central and Eastern Europe, 26 pp., ISBN 978-80-972060-1-7, 2015.

Hagenlocher, M., Naumann, G., Meza, I., Blauhut, V., Cotti, D., Döll, P., Ehlert, K., Gaupp, F., Van Loon, A. F., Marengo, J. A., Rossi, L., Sabino Siemons, A. S., Tsehayu, A. T., Toreti, A., Tsegai, D., Vera, C., Vogt, J., and Wens, M.:. Tackling growing drought risks – the need for a systemic perspective, Earths Future, 11, e2023EF003857, https://doi.org/10.1029/2023EF003857, 2023.

Hall, J. W., Hannaford, J., and Hegerl, G.: Drought risk in the Anthropocene, Philos. T. Roy. Soc. A, 380, 20210297, https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2021.0297, 2022.

Hemachandra, K., Haigh, R., and Amaratunga, D.: Enablers for effective multi-hazard early warning system: a literature review, in: ICSECM 2019, Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering, edited by: Dissanayake, R., Mendis, P., Weerasekera, K., De Silva, S., and Fernando, S., Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd., 94, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-7222-7_33, 2021.

IDMP: Drought and Water Scarcity, WMO No. 1284. Global Water Partnership, Stockholm, Sweden and World Meteorological Organization, Geneva, Switzerland, ISBN 978-92-63-11284-2, 2022.

IDMP: Drought policies and plans, International Drought Management Programme, https://www.droughtmanagement.info/drought-policies-and-plans/, last access: 30 August 2024.

IDMP: Drought Resilience +10 Conference Conclusions and Recommendations, International Drought Management Programme, 30 September–2 October 2024, Geneva, Switzerland, https://www.droughtmanagement.info/hmndp10/about/conference/, last access: 7 March 2025.

Iglesias, A., Cancelliere, A., Gabiña, D., López-Francos, A., Moneo, M., and Rossi, G. (Eds.): Drought management guidelines, European Commission – EuropeAid Co-operation Office Euro-Mediterranean Regional Programme for Local Water Management (MEDA Water) Mediterranean Drought Preparedness and Mitigation Planning (MEDROPLAN), 78 pp., https://projects.iamz.ciheam.org/medroplan/guidelines/archivos/example_guidelines_english.pdf (last access: 29 June 2025), 2007.

Iglesias, A., Garrote, L., Bardají, I., Santillán, D., and Esteve, P.: Looking into individual choices and local realities to define adaptation options to drought and climate change, J. Environ. Manage., 293, 112861, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.112861, 2021.

IPCC: Summary for Policymakers, in: Climate change 2021: the physical science basis, Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, edited by: Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pirani, A., Connors, S. L., Péan, C., Berger, S., Caud, N., Chen, Y., Goldfarb, L., Gomis, M. I., Huang, M., Leitzell, K., Lonnoy, E., Matthews, J. B. R., Maycock, T. K., Waterfield, T., Yelekçi, O., Yu, R., and Zhou, B., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 3–32, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157896.001, 2021.

IPCC: Summary for policymakers, in: Climate change 2022: impacts, adaptation and vulnerability, Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, edited by: Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D. C., Tignor, M., Poloczanska, E. S., Mintenbeck, K., Alegría, A., Craig, M., Langsdorf, S., Löschke, S., Möller, V., Okem, A., and Rama, B., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, 3–33, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009325844.001, 2022.

Jedd, T. and Smith, K. H.: Drought-stricken U.S. states have more comprehensive water-related hazard planning, Water Resour. Manag., 37, 601–617, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11269-022-03390-z, 2023.

Jedd, T., Fragaszy, S. R., Knutson, C., Hayes, M. J., Fraj, M. B., Wall, N., Svoboda, M., and McDonnell, R.: Drought management norms: is the Middle East and North Africa region managing risks or crises?, J. Environ. Dev., 30, 3–40, https://doi.org/10.1177/1070496520960204, 2021.

Kron, W., Schlüter-Mayr, S., and Steuer, M.: Drought aspects – fostering resilience through insurance, Water Policy, 18, 9–27, https://doi.org/10.2166/wp.2016.111, 2016.

Littell, J. S., Peterson, D. L., Riley, K. L., Liu, Y., and Luce, C. H.: A review of the relationships between drought and forest fire in the United States, Glob. Change Biol., 22, 2353–2369, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.13275, 2016.

Marj, A. H. and Abadi, F. H. H.: A nine-step approach for developing and implementing an “agricultural drought risk management plan”; case study: Alamut River Basin in Qazvin, Iran, Nat. Hazards, 102, 1187–1205, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-020-03952-7, 2020.

Masih, I., Maskey, S., Mussá, F. E. F., and Trambauer, P.: A review of droughts on the African continent: a geospatial and long-term perspective, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 18, 3635–3649, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-18-3635-2014, 2014.

Mondal, S., Mishra, A. K., Leung, R., and Cook, B.: Global droughts connected by linkages between drought hubs, Nat. Commun., 14, 144, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-35531-8, 2023.

Mukherjee, S., Mishra, A., and Trenberth, K. E.: Climate change and drought: a perspective on drought indices, Current Climate Change Reports, 4, 145–163, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40641-018-0098-x, 2018.

Naumann, G., Cammalleri, C., Mentaschi, L., and Feyen, L.: Increased economic drought impacts in Europe with anthropogenic warming, Nat. Clim. Change, 11, 485–491, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-021-01044-3, 2021.

NDMC Planning: Planning Processes, National Drought Mitigation Center, University of Nebraska, https://drought.unl.edu/Planning/PlanningProcesses.aspx, last access: 30 August 2024.

Nones, M., Hamidifar, H., and Shahabi-Haghighi, S. M. B.: Exploring EM-DAT for depicting spatiotemporal trends of drought and wildfires and their connections with anthropogenic pressure, Nat. Hazards 120, 957–973, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-023-06209-1, 2024.

Oswald, J. and Harris, S.: Desertification, in: Biological and environmental hazards, risks, and disasters, edited by: Sivanpillai, R. and Schroder, J. F., 2nd edn., Elsevier, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-820509-9.00023-X, 2023.

Otkin, J. A., Svoboda, M., Hunt, E. D., Ford, T. W., Anderson, M. C., Hain, C., and Basara, J. B.: Flash droughts: a review and assessment of the challenges imposed by rapid-onset droughts in the United States, B. Am. Meteorol. Soc., 99, 911–919, https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-17-0149.1, 2018.

Rakovec, O., Samaniego, L., Hari, V., Markonis, Y., Moravec, V., Thober, S., Hanel, M., and Kumar, R.: The 2018–2020 multi-year drought sets a new benchmark in Europe, Earths Future, 10, e2021EF002394, https://doi.org/10.1029/2021EF002394, 2022.

Reckien, D., Magnan, A. K., Singh, C., Lukas-Sithole, M., Orlove, B., Schipper, E. L. F., and Coughlan de Perez, E.: Navigating the continuum between adaptation and maladaptation, Nat. Clim. Change, 13, 907–918, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-023-01774-6, 2023.

Rossi, G. and Castiglione, L.: Towards guidelines for drought preparedness and mitigation planning within EU water policy, European Water, 36, 37–51, 2011.

Rossi, G., Castiglione, L., and Bonaccorso, B.: Guidelines for planning and implementing drought mitigation measures, in: Methods and Tools for Drought Analysis and Management, edited by: Rossi, G., Vega, T., and Bonaccorso, B., Water Science and Technology Library, vol. 62, Springer, Dordrecht, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-5924-7_16, 2007.

Rossi, L., Wens, M., De Moel, H., Cotti, D., Sabino Siemons, A.-S., Toreti, A., Maetens, W., Masante, D., Van Loon, A., Hagenlocher, M., Rudari, R., Meroni, M., Isabellon, M., Avanzi, F., Naumann, G., and Barbosa P.: European drought risk atlas, Publications office of the European Union, Luxembourg, JRC135215, 108 pp., https://doi.org/10.2760/608737, 2023.

Sivakumar, M. V. K., Stefanski, R., Bazza, M., Zelaya, S., Wilhite, D., and Magalhaes, A. R.: High level meeting on national drought policy: summary and major outcomes, Weather and Climate Extremes, 3, 126–132, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wace.2014.03.007, 2014.

Spinoni, J., Barbosa, P., De Jager, A., McCormick, N., Naumann, G., Vogt, J. V., Magni, D., Masante, D., and Mazzeschi, M.: A new global database of meteorological drought events from 1951 to 2016, Journal of Hydrology: Regional Studies, 22, 100593, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrh.2019.100593, 2019.

Steinemann, A. C. and Cavalcanti, L. F. N.: Developing multiple indicators and triggers for drought plans, J. Water Res. Pl., 132, 164–174, https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9496(2006)132:3(164), 2006.

Stringer, L. C., Dyer, J. C., Reed, M. S., Dougill, A. J., Twyman, C., and Mkwambisi, D.: Adaptations to climate change, drought and desertification: local insights to enhance policy in Southern Africa, Environ. Sci. Pol., 12, 748–765, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2009.04.002, 2009.

Tabari, H. and Willems, P.: Sustainable development substantially reduces the risk of future drought impacts, Communications Earth & Environment, 4, 180, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-023-00840-3, 2023.

Tadesse, M. A., Shiferaw, B. A., and Erenstein, O.: Weather index insurance for managing drought risk in smallholder agriculture: lessons and policy implications for sub-Saharan Africa, Agricultural and Food Economics, 3, 26, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40100-015-0044-3, 2015.

Tsegai, D., Liebe, J., and Ardakanian, R. (Eds.).: Capacity development to support national drought management policies. UN-Water Decade Programme on Capacity Development (UNW-DPC), Bonn, Germany, https://www.droughtmanagement.info/literature/UNW-DPC_Synthesis_Capacity_Development_to_Support_NDMP_2015.pdf (last access: 29 June 2025), 2015.

Tubi, A. and Israeli, Y.: Is climate migration successful adaptation or maladaptation? A holistic assessment of outcomes in Kenya, Climate Risk Management, 44, 100614, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crm.2024.100614, 2024.

UNCCD: Strategic framework for drought risk management and enhancing resilience in Africa: White Paper, The United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD), Bonn, Germany, 44 pp., ISBN 978-92-95110-77-9, 2018.

UNCCD: Drought resilience, adaptation and management policy framework: supporting technical guidelines, The United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD), Bonn, Germany, 48 pp., https://www.unccd.int/sites/default/files/relevant-links/2019-09/190906%20UNCCD%20drought%20resilience%20technical%20guideline%20EN.pdf (last access: 29 June 2025), 2019.

UNCCD: Addressing desertification, land degradation and drought: from commitments to implementation, The United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD), Bonn, Germany, 20 pp., https://www.unccd.int/sites/default/files/2022-05/Addressing%20desertification%2C%20land%20 degradation%20and%20drought%20-%20From%20commitments%20to%20implementation.pdf (last access: 29 June 2025), 2022.

UNDRR: Disaster risk reduction, The Sendai Framework Terminology on Disaster Risk Reduction, https://www.undrr.org/terminology/disaster-risk-reduction (last access: 3 March 2025), 2017.

UNDRR: GAR (Global Assessment Report): special report on drought 2021, Geneva, Switzerland, 210 pp., ISBN 9789212320274, 2021.

UNDRR: Policy brief: Towards risk-informed implementation of the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. Geneva, Switzerland, UNDRR Policy Brief No. 4, 6 pp., https://www.undrr.org/publication/policy-brief-towards-risk-informed-implementation-2030-agenda-sustainable-development (last access: 29 June 2025), 2022.

UNDRR and WMO: Global status of multi-hazard early warning systems, Geneva, Switzerland, 138 pp., https://www.undrr.org/media/91954/download?startDownload=20250629 (last access: 29 June 2025), 2023.

UNEP: Progress on integrated water resources management, Tracking SDG 6 series: global indicator 6.5.1 updates and acceleration needs, 110 pp., ISBN 978-92-807-3878-0, 2021.

UNISDR: Hyogo Framework for Action 2005–2015: building the resilience of nations and communities to disasters, Extract from the final report of the World Conference on Disaster Reduction (A/CONF.206/6), UN/ISDR-07-2007-Geneva, Switzerland, 28 pp., https://www.unisdr.org/files/1037_hyogoframeworkforactionenglish.pdf (last access: 29 June 2025), 2005.

UNISDR: Drought risk reduction framework and practices: contributing to the implementation of the Hyogo Framework for action, preliminary version, United Nations secretariat of the International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (UN/ISDR), Geneva, Switzerland, 98 + vi pp., https://www.unisdr.org/files/3608_droughtriskreduction.pdf (last access: 29 June 2025), 2007.

UNISDR: Drought risk reduction framework and practices: contributing to the implementation of the Hyogo Framework for action, United Nations secretariat of the International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (UNISDR), Geneva, Switzerland, 213 pp., https://www.unisdr.org/files/11541_DroughtRiskReduction2009library.pdf (last access: 29 June 2025), 2009.

UNISDR: Sendai Framework for disaster risk reduction 2015–2030, 1st edn., UNISDR/GE/2015 – ICLUX EN5000, Geneva, Switzerland, 37 pp., https://www.undrr.org/media/16176/download?startDownload=20250629 (last access: 29 June 2025), 2015.

UNISDR: Strategic framework 2016–2021, in support of the SENDAI Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030, Geneva, Switzerland, 16 pp., https://www.unisdr.org/files/51557_unisdrstrategicframework20162021pri.pdf (last access: 29 June 2025), 2017.

UNISDR, UNDP, and IUCN: Making disaster risk reduction gender-sensitive: policy and practical guidelines, Geneva, Switzerland, 163 pp., https://www.undrr.org/publication/making-disaster-risk-reduction-gender-sensitive-policy-and-practical-guidelines (last access: 29 June 2025), 2009.

Van Loon, A. F. and Van Lanen, H. A.: Making the distinction between water scarcity and drought using an observation-modeling framework, Water Resour. Res., 49, 1483–1502, https://doi.org/10.1002/wrcr.20147, 2013.

Van Loon, A. F., Gleeson, T., Clark, J., Van Dijk, A. I., Stahl, K., Hannaford, J., Di Baldassarre, G., Teuling, A. J., Tallaksen, L. M., Uijlenhoet, R., and Hannah, D. M.: Drought in the Anthropocene, Nat. Geosci., 9, 89–91, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo2646, 2016.

Van Loon, A. F., Rangecroft, S., Coxon, G., Werner, M., Wanders, N., Baldassarre, G. D., Tijdeman, E., Bosman, M., Gleeson, T., Nauditt, A., Aghakouchak, A., Breña-Naranjo, J. A., Cenobio-Cruz, O., Costa, A. C., Fendekova, M., Jewitt, G., Kingston, D. G., Loft, J., Mager, S. M., Mallakpour, I., Masih, I., Maureira-Cortés, H., Toth, E., Van Oel, P., Van Ogtrop, F., Verbist, K., Vidal, J.-P., Wen, L., Yu, M., Yuan, X., Zhang, M., and Van Lanen, H. A. J.: Streamflow droughts aggravated by human activities despite management, Environ. Res. Lett., 17, 044059, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ac5def, 2022.

Van Loon, A. F., Kchouk, S., Matanó, A., Tootoonchi, F., Alvarez-Garreton, C., Hassaballah, K. E. A., Wu, M., Wens, M. L. K., Shyrokaya, A., Ridolfi, E., Biella, R., Nagavciuc, V., Barendrecht, M. H., Bastos, A., Cavalcante, L., de Vries, F. T., Garcia, M., Mård, J., Streefkerk, I. N., Teutschbein, C., Tootoonchi, R., Weesie, R., Aich, V., Boisier, J. P., Di Baldassarre, G., Du, Y., Galleguillos, M., Garreaud, R., Ionita, M., Khatami, S., Koehler, J. K. L., Luce, C. H., Maskey, S., Mendoza, H. D., Mwangi, M. N., Pechlivanidis, I. G., Ribeiro Neto, G. G., Roy, T., Stefanski, R., Trambauer, P., Koebele, E. A., Vico, G., and Werner, M.: Review article: Drought as a continuum – memory effects in interlinked hydrological, ecological, and social systems, Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci., 24, 3173–3205, https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-24-3173-2024, 2024.

Verbist, K., Amani A., Mishra, A., and Cisneros B. J.: Strengthening drought risk management policy: UNESCO International Hydrological Programme's case studies from Africa and Latin America and the Caribbean, Water Policy, 18, 245–261, https://doi.org/10.2166/wp.2016.223, 2016.

Vogel, R. M. and Kroll, C. N.: On the need for streamflow drought frequency guidelines in the U.S., Water Policy, 23, 216–231, https://doi.org/10.2166/wp.2021.244, 2021.

Vogt, J. V., Naumann, G., Masante, D., Spinoni, J., Cammalleri, C., Erian, W., Pischke, F., Pulwarty, R., and Barbosa, P.: Drought risk assessment: a conceptual framework, EUR 29464 EN, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, JRC113937, 68 pp., ISBN 978-92-79-97469-4, https://doi.org/10.2760/057223, 2018.

Walker, D. W., Salman, M., Pek, E., Stefanski, R., and Aich, V.: Guidelines on institutional coordination for drought management, FAO, Rome, https://doi.org/10.4060/cd2282en, 2024.

Ward, P. J., de Ruiter, M. C., Mård, J., Schröter, K., Van Loon, A., Veldkamp, T., von Uexkull, N., Wanders, N., AghaKouchak, A., Arnbjerg-Nielsen, K., Capewell, L. Llasat, M. C., Day, R., Dewals, B., Baldassarre, G. D., Huning, L. S., Kreibich, H., Mazzoleni, M., Savelli, E., Teutschbein, C., van den Berg, H., van der Heijden, A., Vincken, J. M. R., Waterloo, M. J., and Wens, M.: The need to integrate flood and drought disaster risk reduction strategies, Water Security, 11, 100070, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasec.2020.100070, 2020.

Wilhite, D. A.: Drought planning: A process for state government, Journal of American Water Resources Association, 27, 29–38, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-1688.1991.tb03110.x, 1991.

Wilhite, D. A., Hayes, M. J., Knutson, C., and Smith, K. H., Planning for drought: Moving from crisis to risk management, Journal of American Water Resources Association, 36, 697–710, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-1688.2000.tb04299.x, 2000.

Wilhite, D. A., Svoboda, M. D., and Hayes, M. J.: Understanding the complex impacts of drought: a key to enhancing drought mitigation and preparedness, Water Resour. Manag., 21, 763–774, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11269-006-9076-5, 2007.

WMO and GWP: National drought management policy guidelines: a template for action (D. A. Wilhite), Integrated Drought Management Programme (IDMP) Tools and Guidelines Series 1, WMO, Geneva, Switzerland and GWP, Stockholm, Sweden, 48 pp., ISBN 978-92-63-11164-7, 2014.

WMO and GWP: Handbook of drought indicators and indices (M. Svoboda and B. A. Fuchs), Integrated Drought Management Programme (IDMP), Integrated Drought Management Tools and Guidelines Series 2, Geneva, 52 pp., ISBN 978-92-63-11173-9, 2016.

World Bank: The SENDAI report: managing disaster risks for a resilient future, Washington DC, Rep. 80608, 68 pp., https://hdl.handle.net/10986/23745 (last access: 30 June 2025), 2012.

World Bank: Assessing Drought Hazard and Risk: Principles and Implementation Guidance, Washington, DC, 88 pp., https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/989851589954985863/assessing-drought-hazard-and-risk-principles-and-implementation-guidance (last access: 30 June 2025), 2019.

World Bank: Disaster resilient and responsive public financial management: an assessment tool, Washington, DC, 36 pp., https://hdl.handle.net/10986/37033 (last access: 30 June 2025), 2022.

World Bank and European Commission: Financially Prepared: The Case for Pre-positioned Finance in European Union Member States and Countries under EU Civil Protection Mechanism, Washington, DC, 84 pp., https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099050624175015282/pdf/P179070-7378daf4-a6b2-4ab8-bf82-49ed44c62b9d.pdf (last access: 30 June 2025), 2024.

Yuan, X., Wang, Y., Ji, P., Wu, P., Sheffield, J., and Otkin, J. A.: A global transition to flash droughts under climate change, Science, 380, 187–191, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abn6301, 2023.

Zhang, X., Chen, N., Sheng, H., Ip, C., Yang, L., Chen, Y., Sang, Z., Tadesse, T., Lim, T. P. Y., Rajabifard, A., and Bueti, C.: Urban drought challenge to 2030 sustainable development goals, Sci. Total Environ., 693, 133536, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.07.342, 2019.

Zscheischler, J., Westra, S., Van Den Hurk, B. J., Seneviratne, S. I., Ward, P. J., Pitman, A., AghaKouchak, A., Bresch, D. N., Leonard, M., Wahl, T., and Zhang, X.: Future climate risk from compound events, Nat. Clim. Change, 8, 469–477, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0156-3, 2018.